Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Times a Comienzos Del Siglo XIX

09. Elías Durán de Porras:Articulo 17/02/2010 11:50 Página 1 Henry Crabb Robinson y la sección internacional de The Times a comienzos del siglo XIX Elías DURÁN DE PORRAS Universidad CEU Cardenal Herrera [email protected] Recibido: 1 de Septiembre de 2008 Aceptado: 2 de Febrero de 2009 RESUMEN En 1808 el director de The Times, John Walter II, decidió enviar a España a su mejor periodista para cubrir los inicios de la Guerra de la Independencia. Henry Crabb Robinson puso en práctica en nuestro país su expe- riencia como enviado especial o corresponsal de prensa en Altona, donde siguió de cerca la política de Napoleón en Centroeuropa. Robinson, formado en la Filosofía y las letras alemanas, aprovechó su estancia para analizar el periodismo del Continente y compararlo con el inglés. De su trabajo salió un informe para su director en el que expuso los cambios necesarios para mejorar la sección de Internacional de The Times y pro- fesionalizar el trabajo de los periodistas. Palabras clave: The Times, The Morning Chronicle, Henry Crabb Robinson, Altona, The Morning Herald, John Walter II, Jena, La Coruña, Londres Henry Crabb Robinson and the International News of The Times at the beginning of the 19th Century ABSTRACT In 1808, the editor of the Times, John Walter II, decided to send his best journalist to Spain to cover the begin- nings of the Peninsular War. Henry Crabb Robinson set up in our country his experience as correspondent in Altona, where he covered the Napoleon´s politics in Europe. Educated in the German Philosophy and litera- ture, Robinson spent some time in Altona analysing the diaries of the continent and making a comparison with the British ones. -

Scottsih Newspapers Have a Long Hisotry Fof Involvement With

68th IFLA Council and General Conference August 18-24, 2002 Code Number: 051-127-E Division Number: V Professional Group: Newspapers RT Joint Meeting with: - Meeting Number: 127 Simultaneous Interpretation: - Scottish Newspapers and Scottish National Identity in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries I.G.C. Hutchison University of Stirling Stirling, UK Abstract: Scotland is distinctive within the United Kingdom newspaper industry both because more people read papers and also because Scots overwhelmingly prefer to read home-produced organs. The London ‘national’ press titles have never managed to penetrate and dominate in Scotland to the preponderant extent that they have achieved in provincial England and Wales. This is true both of the market for daily and for Sunday papers. There is also a flourishing Scottish local weekly sector, with proportionately more titles than in England and a very healthy circulation total. Some of the reasons for this difference may be ascribed to the higher levels of education obtaining in Scotland. But the more influential factor is that Scotland has retained distinctive institutions, despite being part of Great Britain for almost exactly three hundred years. The state church, the education system and the law have not been assimilated to any significant amount with their counterparts south of the border. In the nineteenth century in particular, religious disputes in Scotland generated a huge amount of interest. Sport in Scotlaand, too, is emphatically not the same as in England, whether in terms of organisation or in relative popularity. Additionally, the menu of major political issues in Scotland often has been and is quite divergent from England – for instance, the land question and self-government. -

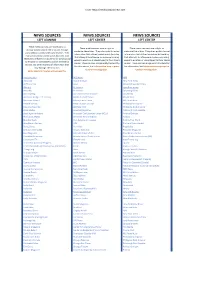

Left Media Bias List

From -https://mediabiasfactcheck.com NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES LEFT LEANING LEFT CENTER LEFT CENTER These media sources are moderately to These media sources have a slight to These media sources have a slight to strongly biased toward liberal causes through moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual story selection and/or political affiliation. They information that utilizes loaded words (wording information that utilizes loaded words (wording may utilize strong loaded words (wording that that attempts to influence an audience by using that attempts to influence an audience by using attempts to influence an audience by using appeal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal to emotion or stereotypes), publish misleading causes. These sources are generally trustworthy causes. These sources are generally trustworthy reports and omit reporting of information that for information, but Information may require for information, but Information may require may damage liberal causes. further investigation. further investigation. Some sources may be untrustworthy. Addicting Info ABC News NPR Advocate Above the Law New York Times All That’s Fab Aeon Oil and Water Don’t Mix Alternet Al Jazeera openDemocracy Amandla Al Monitor Opposing Views AmericaBlog Alan Guttmacher Institute Ozy Media American Bridge 21st Century Alaska Dispatch News PanAm Post American News X Albany Times-Union PBS News Hour Backed by Fact Akron Beacon -

Villages Daily Sun Inks Press, Postpress Deals for New Production

www.newsandtech.com www.newsandtech.com September/October 2019 The premier resource for insight, analysis and technology integration in newspaper and hybrid operations and production. Villages Daily Sun inks press, postpress deals for new production facility u BY TARA MCMEEKIN CONTRIBUTING WRITER The Villages (Florida) Daily Sun is on the list of publishers which is nearer to Orlando. But with development trending as winning the good fight when it comes to community news- it is, Sprung said The Daily Sun will soon be at the center of the papering. The paper’s circulation is just over 60,000, and KBA Photo: expanded community. — thanks to rapid growth in the community — that number is steadily climbing. Some 120,000 people already call The Partnerships key Villages home, and approximately 300 new houses are being Choosing vendors to supply various parts of the workflow at built there every month. the new facility has been about forming partnerships, accord- To keep pace with the growth, The Daily Sun purchased a Pictured following the contract ing to Sprung. Cost is obviously a consideration, but success brand-new 100,000-square-foot production facility and new signing for a new KBA press in ultimately depends on relationships, he said — both with the Florida: Jim Sprung, associate printing equipment. The publisher is confident the investment publisher for The Villages Media community The Daily Sun serves and the technology providers will help further entrench The Daily Sun as the definitive news- Group; Winfried Schenker, senior who help to produce the printed product. paper publisher and printer in the region. -

The Old New Journalism?

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output The development and impact of campaigning journal- ism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40128/ Version: Full Version Citation: Score, Melissa Jean (2015) The development and impact of campaigning journalism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London The Development and Impact of Campaigning Journalism in Britain, 1840–1875: The Old New Journalism? Melissa Jean Score Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I, Melissa Jean Score, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signed declaration_________________________________________ Date_____________________ 3 Abstract This thesis examines the development of campaigning writing in newspapers and periodicals between 1840 and 1875 and its relationship to concepts of Old and New Journalism. Campaigning is often regarded as characteristic of the New Journalism of the fin de siècle, particularly in the form associated with W. T. Stead at the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s. New Journalism was persuasive, opinionated, and sensational. It displayed characteristics of the American mass-circulation press, including eye-catching headlines on newspaper front pages. The period covered by this thesis begins in 1840, with the Chartist Northern Star as the hub of a campaign on behalf of the leaders of the Newport rising of November 1839. -

From Valmy to Waterloo: France at War, 1792–1815

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-08 - PalgraveConnect Tromsoe i - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230294981 - From Valmy to Waterloo, Marie-Cecile Thoral War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850 Series Editors: Rafe Blaufarb (Tallahassee, USA), Alan Forrest (York, UK), and Karen Hagemann (Chapel Hill, USA) Editorial Board: Michael Broers (Oxford, UK), Christopher Bayly (Cambridge, UK), Richard Bessel (York, UK), Sarah Chambers (Minneapolis, USA), Laurent Dubois (Durham, USA), Etienne François (Berlin, Germany), Janet Hartley (London, UK), Wayne Lee (Chapel Hill, USA), Jane Rendall (York, UK), Reinhard Stauber (Klagenfurt, Austria) Titles include: Richard Bessel, Nicholas Guyatt and Jane Rendall (editors) WAR, EMPIRE AND SLAVERY, 1770–1830 Alan Forrest and Peter H. Wilson (editors) THE BEE AND THE EAGLE Napoleonic France and the End of the Holy Roman Empire, 1806 Alan Forrest, Karen Hagemann and Jane Rendall (editors) SOLDIERS, CITIZENS AND CIVILIANS Experiences and Perceptions of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1790–1820 Karen Hagemann, Gisela Mettele and Jane Rendall (editors) GENDER, WAR AND POLITICS Transatlantic Perspectives, 1755–1830 Marie-Cécile Thoral FROM VALMY TO WATERLOO France at War, 1792–1815 Forthcoming: Michael Broers, Agustin Guimera and Peter Hick (editors) THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE AND THE NEW EUROPEAN POLITICAL CULTURE Alan Forrest, Etienne François and Karen Hagemann -

James Perry and the Morning Chronicle 179O—I821

I JAMES PERRY AND THE MORNING CHRONICLE- 179O—I821 By l yon Asquith Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London 1973 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Preface 5 1. 1790-1794 6 2. 1795-1 805 75 3. 1806-1812 (i) ThB Ministry of the Talents 184 (ii) Reform, Radicalism and the War 1808-12 210 (iii) The Whigs arid the Morning Chronicle 269 4. Perry's Advertising Policy 314 Appendix A: Costs of Production 363 Appendix B: Advertising Profits 365 Appendix C: Government Advertisements 367 5. 1813-1821 368 Conclusion 459 Bibliography 467 3 A BSTRACT This thesis is a study of the career of James Perry, editor and proprietor of the Morning Chronicle, from 1790-1821. Based on an examination of the correspondence of whig and radical polit- icians, and of the files of the morning Chronicle, it illustrates the impact which Perry made on the world of politics and journalism. The main questions discussed are how Perry responded, as a Foxite journalist, to the chief political issues of the day; the extent to which the whigs attempted to influence his editorial policy and the degree to which he reconciled his independence with obedience to their wishes4 the difficulties he encountered as the spokesman of an often divided party; his considerable involvement, which was remarkable for a journalist, in party activity and in the social life of whig politicians; and his success as a newspaper proprietor concerned not only with political propaganda, but with conducting a paper which was distinguished for the quality of its miscellaneous features and for its profitability as a business enterprise. -

Character Appraisal & Management Plan Conservation Area

LONDON BOROUGH OF RICHMOND UPON THAMES Character Appraisal & Management Plan Conservation Area – Blackmore’s Grove no.39 This study cannot realistically cover every aspect This study was approved by the Council’s of quality and the omission of any particular building Cabinet Member for Environment and Planning feature or space should not be taken to mean that it on 12 January 2006. is not of interest. The illustrations were produced by Howard Vie. O RIGINS AND DEVE L OPMEN T Conservation areas were introduced in the Civic OF TEDDINGTON Amenities Act 1967 and are defined as areas of ‘special architectural or historic interest, the character or There is evidence of human activity in Teddington from pre- appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or historic times. The name Teddington is derived from the enhance’. Designation introduces a general control Anglo-Saxon meaning: ‘Tudas Farm’. The original settlement over the total demolition of unlisted buildings and the was on the river terrace, elevated from the flood plain of felling or lopping of trees above a certain size. the Thames. Situated not far from Bushy Park and Hampton Court Palace, it was the property of Westminster Abbey The objective of a conservation area study is to before becoming part of Henry VIII’s hunting estate in the provide a clearly defined analysis of the character and C16, after which time it returned to being an independent appearance of the conservation area, defensible on manor. appeal, and to assist in development control decisions. Further, to address issues, which have been identified Long dependant on agriculture as its economic base, its rural in the character appraisal process, for the enhancement setting and riverside location attracted wealthy residents. -

The Times All the Crowd-Pleasing Tales of the Latest Scandals, and Gossip About the Famous of London

READ NOT: And yet — in fact you need only draw a single thread at any point you choose out of the fabric of life and the run will make a pathway across the whole, and down that wider pathway each of the other threads will become successively visible, one by one. — Heimito von Doderer, DIE DÂIMONEN HDT WHAT? INDEX TIMES OF LONDON TIMES OF LONDON 1785 January 1: John Walter’s career as an insurance underwriter at Lloyds of London had come to an unexpected sudden end in a flurry of insurance claims arising out of a hurricane in Jamaica. He was close to bankruptcy, but had become aware that an advanced method of typesetting allowing for more than one letter to be set at a time, called “logography,” had just been invented by Henry Johnson. Not only did this new method promise greater speed of typesetting, it also promised fewer typesetting errors. Purchasing Johnson’s patent, Walker set out to create a printing company to put out a daily advertising sheet that profitably would demonstrate this promising new technological efficiency to all — and thus make sales for it. On this day the 1st edition of his Daily Universal Register was put out for sale on London streets. The sheet was in head-on competition with eight other daily newspapers in London. Like these other newspapers, it would include parliamentary reports and foreign news, as well as its advertisements. Walter, however, was primarily concerned with the advertising revenue stream which the sheet should generate: “The Register, in its politics, will be of no party. -

Beheftal O F Electricity Never Have Rheumatism Or Now Type

gite €Ulou (Tribune. j Dellciouinn« t>i Rusiian Tea. Till! LONDON TIMES. Tho cuisiuo iu tho hotel aud good re C L H Ü-A-T «T fT I stuurnnts is very Hue, and comfortably A WELL KNOWN CORRESPONDENTS good in tho cheaper houses wo havo tried- Wholoealo Coaler in ’ CRICKET SONG. ! Nowhere is living dear. Tea, most deli ACCOUNT OF THE JOURNAL. cious, with nice bread, uud enough for Chirp, umd cricket. In the grain— ! two, cost eighty kopecks, aud utriuk gelt Chirp, tiling garrulous and free; I to tho waiter of say teu—in all about If thy ciiirping could bo words, Tlie Fnmou» Xew»|m|H>r'» Ilcgiuuiiig One Teil me wlrnt tlio words would bet i forty cents. Chocolate, two tumblers WINES, LIQUORS AND CICABS Hundred Year» A go—I’tillllcul .Shifting Chirp shrill, chirp soft, full,’ and bread or cake for two, sarno MANUFACTURER OF l*ipo high, pipe low; of Tho Time»—Hnw IU l*»ge* Aro price. A good dinner of soup, two kinds In vines, aloft, Filled—Editor •lelin Uelunr. meat and vegetables, with a compoto and Iu grain, below; giass of beer, costs in tho best places, for Ginger Ale, Birch Beer, Champion Cider. Sodn a Only tell—were kinds spoke. M. Blowitz, tho well kuown Paris cor- two, about $ 1.10 of our money. Tho If in words thy tumult liroket respondent of The London Times, bus samo at a rcspoctablo placo, but not so rilla, and other Carbonated Beverages’ 8*rWil A G E N T FOR 6 Cricket, would thy words be wiso. -

Analysis of the Front Page of the Houston Post And

ANALYSIS OF THE FRONT PAGE OF THE HOUSTON POST AND HOUSTON CHRONICLE BEFORE AND AFTER THE PURCHASE OF THE HOUSTON POST BY TORONTO SUN PUBLISHING CO. By C. FELICE FUQUA Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1983 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 1986 Tk&si~_, l '1 <3'(p F Q, ANALYSIS OF THE FRONT PAGE OF THE AND HOUSTON CHRONICLE BEFORE AND AFTER THE PURCHASE OF THE HOUSTON POST BY TORONTO SUN PUBLISHING CO. Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate Collegec 1251246 ii PREFACE This is a content analysis of the front page news content of the Houston Post and the Houston Chronicle before and after the Post was bought by Toronto Sun Publishing Co. The study sought to determine if the change in ownership of the Post affected the newspaper's content, and if the news content of the Chronicle also had been affected, producing competition between two traditionally noncompetitive newspapers. Many persons made significant contributions to this paper. I would like to express special thanks to my thesis adviser, Dr. Walter J. Ward, director of graduate studies in mass communication at Oklahoma State_ University. I also express my appreciation to the other members of the thesis committee: Dr. Wi~liam R. Steng, professor of journalism and broadcasting, and Dr. Marlan D. Nelson, direc tor of the School of Journalism and Broadcasting. I very much enjoyed working under Dr. Nelson as his graduate assis assistant. -

You Are What You Read

You are what you read? How newspaper readership is related to views BY BOBBY DUFFY AND LAURA ROWDEN MORI's Social Research Institute works closely with national government, local public services and the not-for-profit sector to understand what works in terms of service delivery, to provide robust evidence for policy makers, and to help politicians understand public priorities. Bobby Duffy is a Research Director and Laura Rowden is a Research Executive in MORI’s Social Research Institute. Contents Summary and conclusions 1 National priorities 5 Who reads what 18 Explaining why attitudes vary 22 Trust and influence 28 Summary and conclusions There is disagreement about the extent to which the media reflect or form opinions. Some believe that they set the agenda but do not tell people what to think about any particular issue, some (often the media themselves) suggest that their power has been overplayed and they mostly just reflect the concerns of the public or other interests, while others suggest they have enormous influence. It is this last view that has gained most support recently. It is argued that as we have become more isolated from each other the media plays a more important role in informing us. At the same time the distinction between reporting and comment has been blurred, and the scope for shaping opinions is therefore greater than ever. Some believe that newspapers have also become more proactive, picking up or even instigating campaigns on single issues of public concern, such as fuel duty or Clause 28. This study aims to shed some more light on newspaper influence, by examining how responses to a key question – what people see as the most important issues facing Britain – vary between readers of different newspapers.