Online Wine Tasting Courses in Norway. Examining the Quality of Corrective Feedback Through an Online Platform and the Opportunities for Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JASON WISE (Director): SOMM 3

Book Reviews 423 JASON WISE (Director): SOMM 3. Written by Christina Wise and Jason Wise, Produced by Forgotten Man Films, Distributed by Samuel Goldwyn Films, 2018; 1 h 18 min. This is the third in a trilogy of documentaries about the wine world from Jason Wise. The first—Somm, a marvelous film which I reviewed for this Journal in 2013 (Stavins, 2013)–followed a group of four thirty-something sommeliers as they prepared for the exam that would permit them to join the Court of Master Sommeliers, the pinnacle of the profession, a level achieved by only 200 people glob- ally over half a century. The second in the series—Somm: Into the Bottle—provided an exploration of the many elements that go into producing a bottle of wine. And the third—Somm 3—unites its predecessors by combining information and evocative scenes with a genuine dramatic arc, which may not have you on pins and needles as the first film did, but nevertheless provides what is needed to create a film that should not be missed by oenophiles, and many others for that matter. Before going further, I must take note of some unfortunate, even tragic events that have recently involved the segment of the wine industry—sommeliers—featured in this and the previous films in the series. Five years after the original Somm was released, a cheating scandal rocked the Court of Master Sommeliers, when the results of the tasting portion of the 2018 exam were invalidated because a proctor had disclosed confidential test information the day of the exam. -

Du Sauvignon

Concours Mondial du Sauvignon M���� 04�� � 5�� 2016 RUEDA (SPAIN) PRESS KIT The Concours Mondial du Sauvignon provides an annually updated snapshot of the global Sauvignon blanc wine industry. Professional judges sharing the same passion for Sauvignon blanc take part in a competition offering an international array of wines made from the varietal. The Concours Mondial du Sauvignon not only endorses excellence by awarding medals, it seeks to create a focal point for the movers and shakers of the global Sauvignon blanc wine industry. A uni�ue and e�clusive competition The Concours Mondial du Sauvignon is more than just a competi ti on between producers and appellati ons. It is primarily aimed at fostering dialogue and creati ng a meeti ng point for industry specialists. Producers, wine makers, sommeliers, distributors, journalists and opinion formers from all strands of the industry – in all more than 50 judges representi ng 20 nati onaliti es - evaluate entries from twenty or so producer countries. The Concours Mondial de Bruxelles has been commissioned to handle the technical organisati on of the tasti ngs and brings to the event the professionalism and independence for which foremost internati onal competi ti ons are renowned. In 2016, the Concours Mondial du Sauvignon goes to Rueda for a two-day event.. In additi on to the two morning tasti ng sessions, valuable additi onal content is off ered during the event. ConCours Mondial du sauvignon 2016 | Press Kit 1 panel members The panel is comprised of hand-picked specialists from around the world. It is responsible for awarding medals to the best entries. -

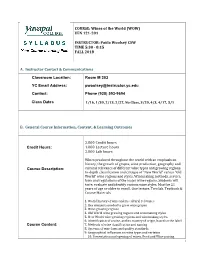

COURSE: Wines of the World (WOW) VEN 121-201 INSTRUCTOR

COURSE: Wines of the World (WOW) VEN 121-201 INSTRUCTOR: Paula Woolsey CSW TIME 5:30 - 8:15 FALL 2018 A. Instructor Contact & Communications Classroom Location: Room M 203 YC Email Address: [email protected] Contact: Phone (928) 593-9694 Class Dates 1/16, 1/30, 2/13, 2/27, No Class, 3/20, 4/3, 4/17, 5/1 B. General Course Information, Content, & Learning Outcomes Credit Hours: 2.000 Credit hours 1.000 Lecture hours 2.000 Lab hours Course Description: Wines produced throughout the world with an emphasis on history, the growth of grapes, wine production, geography and cultural relevance of different wine types and growing regions. In-depth classification and critique of “New World” versus “Old World” wine regions and styles. Winemaking methods, service, laws and regulations of the major wine regions. Students will taste, evaluate and identify various wine styles. Must be 21 years of age or older to enroll. One lecture. Two lab. Textbook & Course Materials 1. World history of wine and its cultural relevance 2. Key elements needed to grow wine grapes 3. Wine growing regions 4. Old World wine growing regions and winemaking styles Course Content: 5. New World wine growing regions and winemaking styles 6. Identification of a wine, and its country of origin, based on the label 7. Methods of wine classification and naming 8. Systems of wine laws and quality standards 9. Geographical influences on wine types and varieties 1 10. Presentation and opening of wines, Food and Wine pairing Upon successful completion of this course, the learner will be able to: 1. -

Blind Wine Tasting

Wine Characteristics Body This refers to the perceived “weight” and viscosity of the wine. A full-bodied wine feels thick, coating the sides of the glass as you swirl. A light-bodied wine is Blind almost like water. A medium-bodied wine is somewhere in-between. Wine Tasting Sweetness Needs no explanation. The opposite of sweet is dry. A wine can also be medium-dry or off-dry (i.e. just a hint of sweetness, but almost too faint to move the needle). Acidity Acidity in wine is tart and zesty. Acidity is a big deal for white wines; it makes them refreshing and crisp. Acidic wines give you a tingling sensation that focuses on the front and sides of your tongue. Tannin It’s all about the tannins for red wine. High tannin wines are astringent and will leave a lingering ? bitter/dry feeling in your mouth. Lower tannin wines are smooth and soft. Whites White #1 White #2 White #3 White #4 White #5 Chardonnay: Fruity and buttery with a velvety Body: Body: Body: Body: Body: feel that’s atypical to dry Full / Medium / Light Full / Medium / Light Full / Medium / Light Full / Medium / Light Full / Medium / Light white wines. Sweetness: Sweetness: Sweetness: Sweetness: Sweetness: Pinot Grigio: Simple, light- Sweet / Off-Dry / Dry Sweet / Off-Dry / Dry Sweet / Off-Dry / Dry Sweet / Off-Dry / Dry Sweet / Off-Dry / Dry bodied, dry and crisp. Riesling: Very sweet with Impressions: Impressions: Impressions: Impressions: Impressions: intense fruit flavors. Highly acidic. Moscato: Fruity, sweet and delicate. Sauvignon Blanc: Dry, tart and acidic with Score (1-10): Score (1-10): Score (1-10): Score (1-10): Score (1-10): herbal flavors, as well as tropical fruit. -

MW SICILY TRIP 12-18 May 2012 Trip Report

MW SICILY TRIP 12-18 May 2012 Trip Report 1 Index Tenuta de Fessina – Ed Adams MW 3 Azienda Cottanera – Tim Atkin MW 5 Frank Cornelissen, Etna –Beverley Blanning MW 7 Azienda Benanti, Etna – Christy Canterbury MW 9 Modica – Jane Skilton MW 12 Gulfi Estate, Ragusa – Jean Michel Valette MW 13 Cerasuolo DOCG – Peter Scudamore-Smith MW 14 Feudi del Pisciotto – Paul Liversedge MW 16 Agrigento temples – Mark Savage MW 17 Feudo Montoni, Cammarata – Pedro Ballesteros Torres MW 18 Tasca d’Almerita, Tenuta Regaleali – Lynne Sherriff MW 19 Planeta Estate, Lago Arancio – Alison Flemming MW 21 De Bartoli, Marsala – John Hoskins MW 24 Donnafugata Estate, Lago Arancio – Anne Tupker MW 27 IRVOS research centre, Marsala – Angela Muir MW 35 Firriato vineyards, Favignana – Susan Hulme MW 37 Tasting with Erice Doc – Jane Boyce MW 38 Custonaci lunch – Christy Canterbury MW 39 Master of Wine Biographies 45 2 MW SICILY TRIP 2012 12th May Tenuta de Fessina – Ed Adams MW Not many MWs one suspects will have visited vineyards on an active volcano before; you know you are on a rather special soil when one of the group comes up to you with a small clump of soil attached like iron filings to the back of their magnetic name badge. It was clear from this first visit that Sicily was going to be unusual and fascinating. Tenuta de Fessina is a 250 year old estate which was purchased in 2007 by Tuscan producers Silvia Maestrelli and Roberto Silva along with Piemontese winemaker Frederico Curtaz. There are 10 hectares under vine, of which 40% is ungrafted. -

European Wine on the Eve of the Railways

Copyrighted Material C H A P T E R 1 European Wine on the Eve of the Railways Wine-making is an art which is subject to important modifications each year. —Nicolás de Bustamente, 1890:103 Wine was an integral part of the population’s diet in much of southern Europe. In France on the eve of the railways, there were reportedly over one and a half million growers in a population of thirty-five million. High transport costs, taxation, and poor quality all reduced market size, and most wines were consumed close to the place of production. Volatile markets also forced most growers to combine viticulture with other economic activities. Alongside the production of cheap table wines, a small but highly dynamic sector existed that specialized in fine wines to be sold as luxury items in foreign markets. In particu- lar, from the late seventeenth century foreign merchants and local growers com- bined to create a wide range of new drinks, primarily for the British market, and in the 1850s wine still accounted for about half of all Portugal’s exports, a quarter of Spain’s, and one-fifteenth of France’s.1 The process of creating wine followed a well-determined sequence: grapes were produced in the vineyard; crushed, fermented, and sometimes matured in the winery; and blended (and perhaps matured further) in the merchant’s cellar; finally, the wine was drunk in a public place or at home. This chapter looks at the major decisions that economic agents faced when carrying out these activities. It examines the nature of wine and the economics of grape and wine production, market organization, and the development of fine wines for export before 1840. -

Château Haut-Brion Owners Buy St. Emilion's Château L'arrosée

SEPTEMBER - OCTOBER 2013 IN THIS ISSUE : Asian Libations - Pairing Wine with Chinese Food . Does Vintage Really Matter? . Brent Lello’s Wine Story Château Haut-Brion Owners Buy Château Latour’s Francois Pinault St. Emilion’s Château L’Arrosée buys Araujo Estate in Napa by: James Molesworth by: Jane Anson This takes the number of wine properties Bart and Daphne Araujo bought Eisele now owned by the French billionaire and Vineyard, located just outside Calistoga, his son Francois-Henri to four – Latour in in 1990, although the vineyard itself dates Pauillac, Château Grillet in the northern back to 1884, and is known particularly Rhone, Domaine d’Eugenie in Vosne- for its Cabernet Sauvignon wines. Romanée and now Araujo in Napa. Pinault also owns Chardonnay vines in After the purchase, they hired Michel Le Montrachet and Batard-Montrachet. Rolland as consultant, and also converted the estate to biodynamic farming – The price of the purchase was not something that Château Latour has itself disclosed, but is likely to have been at been doing over the past few years. least US$300,000 per acre. The sale included the Eisele Vineyard, 38 acres of In a letter to staff and clients, the former vines, the winery and existing stocks. owners said that they had received an unsolicited expression of interest from the Photo source: mybettanedesseauve.fr ‘Araujo Estate and its jewel, the unique Artemis Group, owners of Latour, and Domaine Clarence Dillon, the director of Domaine Clarence Dillon. ‘At Eisele Vineyard, have been producing were slowly convinced that they were ‘the ownership group that includes the this stage, any question about the strategy consistently one of the very best wines of perfect buyers for this amazing vineyard famed first-growth Château Haut- we intend to implement is premature,’ the Napa Valley,’ said Frederic Engerer, we have called home for 23 years’. -

Virtual Experiences Flyer

Corporate Virtual Experiences With conferences canceled and teams working remotely, it has been a challenge to stay connected with your team, clients, and partners who are vital to your business. Paradise Ridge is excited to offer virtual and at-home wine packages to help you reunite & connect - even while apart. Russian River Estate Tasting Kit Blind Wine Tasting Experience $130 per kit + $20 flat rate shipping* $120 - $210 per kit + $20 flat rate shipping* This tasting experience will take a deep dive into the Put your taste buds to the test! Pick between our Red bounty of Paradise through three wines grown here Wine Flight or our White Wine Flight or try them both. on the Estate. This guided tasting includes an Each blind tasting kit comes with three concealed enlightening discussion on our sustainable vineyard Paradise Ridge wines with wine tasting instructions practices and unique terroir, vintage variation, and and worksheets. This experience is the perfect way to artisanal winemaking methods. explore wine and learn something new! Happy Hour $35 - $70 per kit + $15 flat rate shipping* Perfect for Wine Wednesday or any night of the week! Invite your team to a private online hangout, where one of our Paradise Ridge Wine Educators will kick things off with a brief interactive discussion about the bottle of wine they are enjoying - then leaving you to enjoy, relax, and unwind. *custom shipping rates will apply when shipping outside of CA Custom Virtual Tasting Experiences Inquire for pricing Let Paradise Ridge create the perfect experience curated just for your group. Whether you are interested in a theme, have a favorite varietal, or are working within a specific budget, we can plan a virtual event to suit your needs. -

Does Organic Wine Taste Better? an Analysis of Experts’ Ratings

DOES ORGANIC WINE TASTE BETTER? AN ANALYSIS OF EXPERTS’ RATINGS Magali A. Delmas, Olivier Gergaud, and Jinghui Lim1 Abstract Eco-labels are part of a new wave of environmental policy that emphasizes information disclosure as a tool to induce environmentally friendly behavior by both firms and consumers. Little consensus exists as to whether eco-certified products are actually better than their conventional counterparts. This paper seeks to understand the link between eco-certification and product quality. We use data from three leading wine rating publications (Wine Advocate, Wine Enthusiast, and Wine Spectator) to assess quality for 74,148 wines produced in California between 1998 and 2009. Our results indicate that eco-certification is associated with a statistically significant increase in wine quality rating. Keywords: eco-labels, credence goods, information disclosure policy, asymmetric information, product quality. JEL: Q56, Q13, L15, L66, Q21 1 Magali Delmas, Professor of Management, UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability & Anderson School of Management. UCLA La Kretz Hall, Suite 300. Los Angeles CA 90095-1496. Email: [email protected]; Olivier Gergaud, Professor of Economics, KEDGE Business School (Bordeaux campus), 680 Cours de la Libération, 33405 Talence Cedex, France. Email: [email protected] ; Jinghui Lim, UCLA Anderson School of Management, La Kretz Hall, Suite 300 Los Angeles CA 90095-1496, Email: [email protected]. Eco-labels are part of a new wave of environmental policy that emphasizes information disclosure as a tool to induce environmentally conscious behavior by both firms and consumers. The goal of eco-labels is to provide easily understood information, and thereby elicit increased demand for products perceived as environmentally friendly. -

Du Sauvignon

Concours Mondial du Sauvignon MARCH 3RD & 4TH 2017 BORDEAUX (FRANCE) PRESS KIT The Concours Mondial du Sauvignon provides an annually updated snapshot of the global Sauvignon blanc wine industry. Professional judges sharing the same passion for Sauvignon blanc take part in a competition offering an international array of wines made from the varietal. The Concours Mondial du Sauvignon not only endorses excellence by awarding medals, it seeks to create a focal point for the movers and shakers of the global Sauvignon blanc wine industry. A UNIQUE AND EXCLUSIVE COMPETITION The Concours Mondial du Sauvignon is more than just a competition between producers and appellations. It is primarily aimed at fostering dialogue and creating a meeting point for industry specialists. Producers, wine makers, sommeliers, distributors, journalists and opinion formers from all strands of the industry – in all more than 70 judges representing 23 nationalities. In 2017, a panel of judges from the wine industry will evaluate over 900 entries from 24 producer countries worldwide. The Concours Mondial de Bruxelles has been commissioned to handle the technical organisation of the tastings and brings to the event the professionalism and independence for which foremost international competitions are renowned. The eighth Concours Mondial du Sauvignon is returning to Bordeaux where it was founded in 2010 on the initiative of the Bordeaux and Bordeaux Superieur producers’ organisation. This is the fifth time the contest is being held in the city that saw its inception. The region is one of the largest and most renowned producers of quality Sauvignon blanc wines in France, spanning appellations such as Entre-Deux-Mers, Graves and Pessac-Leognan. -

The History of California Wine

Contact: Wine Institute of California Communications Dept. 415/356-7525 [email protected] January 2012 The History of California Wine Winemaking in California began more than 240 years ago. In 1769, Father Junipero Serra, a Franciscan missionary, brought settlers from Mexico into San Diego. He established a mission there and the first known vineyard in California. As he moved north along the route that became known as El Camino Real, he and others established 21 missions linking San Diego in the south to Sonoma in the north. To each, Father Serra brought the cultivation of the grape. The first wines were produced for sacramental purposes and the daily table needs of the missions. The grape variety planted came with the missionaries from Mexico and was known as the Mission grape. About 1830, the commercial era started through the efforts of a Frenchman, Jean Louis Vignes. Arriving from Bordeaux, he saw the land’s potential and soon imported cuttings of many varieties of the native European Vitis vinifera. His vineyard was located in what is now downtown Los Angeles. Shortly thereafter, a group of German Utopians started a large vineyard in Anaheim, now home to the world-famous Disneyland. In 1848, the discovery of gold forever changed the northern half of California. With it came a tremendous increase in population, wealth and settlements. Among those attracted to the pursuit of gold were many immigrants from France, Italy, Germany, Great Britain and other countries. A few struck it rich. Many of those who did not, especially the Europeans, knew much about growing grapes and making wine, and realized that the land offered unlimited potential for vineyards. -

Economics Blind Tasting of South African Wines

AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF WINE ECONOMISTS AAWE WORKING PAPER No. 164 Economics Blind Tasting of South African Wines: A Tale of Two Methodologies Domenic Cicchetti www.wine-economics.org Aug 2014 ISSN 2166-9112 Blind Tasting of South African Wines: A Tale of Two Methodologies Dom Cicchetti, Ph.D. Department of Biometry Yale University School of Medicine New Haven, CT 06520 Keywords: Sauvignon Blanc; Pinotage; replicate tastings; wine rankings; wine scorings 2 Abstract The author compared two methods for assessing the reliability of blind wine tastings of South African Sauvignon Blanc and Pinotage white and red wines. The first method required the taster to rank each of the 8 white and red wines from 1 for the most preferred to 8 for the least preferred, with tied ranks permitted when 2 or more wines were equally preferred. The second used scores representing a taster’s perceived quality of wine as: 50%-69% =Poor/Unacceptable; 70%-79%= Fair/Mediocre; 80%-89%= Good/Above Average; and 90%-100%= Excellent to Superior. Results indicated that the two methods provided quite different results with respect to the critical issue of identifying replicate wines; while the identification of replicate white and red wines proved successful when wine scores were used, not a single wine taster could successfully identify replicate white or red wines when using ranking methods. This finding, plus the fact that very different scorings can produce the very same rankings, such as 1, 2, and 3 being given scores of 60, 64, 66 (Poor/Unacceptable); 70,72, 76 (Fair/Mediocre); 80, 83, 87 (Good/Above Average; and 90, 95, 98.