The Temple in the Book of Mormon: the Temples at the Cities of Nephi, Zarahemla, and Bountiful

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events Earl M. Wunderli DURING THE PAST FEW DECADES, a number of LDS scholars have developed various "limited geography" models of where the events of the Book of Mormon occurred. These models contrast with the traditional western hemisphere model, which is still the most familiar to Book of Mormon readers. Of the various models, the only one to have gained a following is that of John Sorenson, now emeritus professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University. His model puts all the events of the Book of Mormon essentially into southern Mexico and southern Guatemala with the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as the "narrow neck" described in the LDS scripture.1 Under this model, the Jaredites and Nephites/Lamanites were relatively small colonies living concurrently with other peoples in- habiting the rest of the hemisphere. Scholars have challenged Sorenson's model based on archaeological and other external evidence, but lay people like me are caught in the crossfire between the experts.2 We, however, can examine Sorenson's model based on what the Book of Mormon itself says. One advantage of 1. John L. Sorenson, "Digging into the Book of Mormon," Ensign, September 1984, 26- 37; October 1984, 12-23, reprinted by the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS); An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: De- seret Book Company, and Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1985); The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1990); "The Book of Mormon as a Mesoameri- can Record," in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. -

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

Placing the Cardston Temple in Early Mormon Temple Architectural History

PLACING THE CARDSTON TEMPLE IN EARLY MORMON TEMPLE ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY By Amanda Buessecker A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Art History Carleton University May 2020 Supervisor: Peter Coffman, Ph.D. Carleton University ii Abstract: The Cardston temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints represents a drastic shift in temple architecture of the early Mormon faith. The modern granite structure was designed not to show a mere difference of aesthetic taste, but as an embodiment of the evolving relationship between the Mormon pioneers and the American government. Earlier temples, erected in the nineteenth century throughout the valleys of Utah, were constructed by Mormon pioneers at a time when the religious group desired to separate themselves from the United States physically, politically, and architecturally. When the temple was built in Cardston, Alberta (1913-1923), it was a radical departure from its medievalist predecessors in Utah. The selected proposal was a modern Prairie-school style building, a manifestation of Utah’s recent interest in integrating into American society shortly after being admitted to the Union as a state in 1896. iii Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Part I: A Literature Review ........................................................................................................ 5 A Background for Semiotics ................................................................................................. -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Samuel the Lamanite

Samuel the Lamanite S. Michael Wilcox Samuel the Lamanite was the only Book of Mormon prophet identied as a Lamanite. Apart from his sermon at Zarahemla (Hel. 13—15), no other record of his life or ministry is preserved. Noted chiey for his prophecies about the birth of Jesus Christ, his prophetic words, which were later examined, commended, and updated by the risen Jesus (3 Ne. 23:9—13), were recorded by persons who accepted him as a true prophet and even faced losing their lives for believing his message (3 Ne. 1:9). Approximately ve years before Jesus’ birth, Samuel began to preach repentance in Zarahemla. After the incensed Nephite inhabitants expelled him, the voice of the Lord directed him to return. Climbing to the top of the city wall, he delivered his message unharmed, even though certain citizens sought his life (Hel. 16:2). Thereafter, he ed and “was never heard of more among the Nephites” (Hel. 16:8). Samuel prophesied that Jesus would be born in no more than ve years’ time, with two heavenly signs indicating his birth. First, “one day and a night and a day” of continual light would occur (Hel. 14:4; cf. Zech. 14:7). Second, among celestial wonders, a new star would arise (Hel. 14:5—6). Then speaking of mankind’s need of the atonement and resurrection, he prophesied signs of Jesus’ death: three days of darkness among the Nephites would signal his crucixion, accompanied by storms and earthquakes (14:14—27). Samuel framed these prophecies by pronouncing judgments of God upon his hearers. -

Architecture of Light of the Orthodox Temple

DOI: 10.4467/25438700ŚM.17.058.7679 MYROSLAV YATSIV* Architecture of Light of the Orthodox Temple Abstract Main tendencies, appropriateness and features of the embodiment of the architectural and theological essence of the light are defined in architecturally spatial organization of the Orthodox Church; the value of the natural and artificial light is set in forming of symbolic structure of sacral space and architectonics of the church building. Keywords: the Orthodox Church, sacral space, the light, architectonics, functions of the light, a system of illumination, principles of illumination 1. Introduction. The problem raising in such aspect it’s necessary to examine es- As the experience of new-built churches testifies, a process sence and value of the light in space of the of re-conceiving of national traditions and searches of com- Orthodox Church. bination of modern constructions and building technologies In religion and spiritual life of believing peo- last with the traditional architectonic forms of the church bu- ple the light is an important and meaningful ilding in modern church architecture of Ukraine. Some archi- symbol of combination in their imagination tects go by borrowing forms of the Old Russian church archi- of the celestial and earthly worlds. Through tecture, other consider it’s better to inherit the best traditions this it occupies a central place among reli- of wooden and stone churches of the Ukrainian baroque or gious characters which are used in the Saint- realize the ideas of church architecture of the beginning of ed Letter. From the first book of Old Testa- XX. In the east areas the volume-spatial composition of the ment, where the fact of creation of the light Russian “synod-empire” of the church style is renovated as by God is specified: “And God said: “Let it be the “national sign of church architecture” and interpreted as light!”(Genesis 1.3-4), to the last New Testa- the new “Ukrainian Renaissance” [1]. -

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020 (3 credits; MW 10:05-11:25; Oegema; Zoom & Recorded) Instructor: Prof. Dr. Gerbern S. Oegema Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University 3520 University Street Office hours: by appointment Tel. 398-4126 Fax 398-6665 Email: [email protected] Prerequisite: This course presupposes some basic knowledge typically but not exclusively acquired in any of the introductory courses in Hebrew Bible (The Religion of Ancient Israel; Literature of Ancient Israel 1 or 2; The Bible and Western Culture), New Testament (Jesus of Nazareth, New Testament Studies 1 or 2) or Rabbinic Judaism. Contents: The course is meant for undergraduates, who want to learn more about the history of Ancient Judaism, which roughly dates from 300 BCE to 200 CE. In this period, which is characterized by a growing Greek and Roman influence on the Jewish culture in Palestine and in the Diaspora, the canon of the Hebrew Bible came to a close, the Biblical books were translated into Greek, the Jewish people lost their national independence, and, most important, two new religions came into being: Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism. In the course, which is divided into three modules of each four weeks, we will learn more about the main historical events and the political parties (Hasmonaeans, Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, etc.), the religious and philosophical concepts of the period (Torah, Ethics, Freedom, Political Ideals, Messianic Kingdom, Afterlife, etc.), and the various Torah interpretations of the time. A basic knowledge of this period is therefore essential for a deeper understanding of the formation of the two new religions, Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism, and for a better understanding of the growing importance, history and Biblical interpretation have had for Ancient Judaism. -

The Zarahemla Record September 1978

THEZARAHEMLA RECORD /ssueNumber 2 September 1978 "And he that witl not harden his heart, to him is given the greater portion of the word..." Alma 9: 18 The MORMON BOOKOF Endof JareditesArrive Jaredite Division and Culture of People- MESOAMERICAN OutlinesCompared: Beginning, Highpointsand Endings First Pottery Endof Olmec Maya Glyphs Appears Culture Begin By RaymondC. Treat The most importanttype of evidenceat the presenttime time range. The first pottery is clatedwithin this range. The so- supportingthe Bookof Mormonis a correlationof the outlines called Pox pottery from Puerto Marquez, Guerrero and the of the Book of Mormon and Mesoamericanarchaeology at Tehuacan Valley is dated 2300-2M B.C. and the newly strategic points along the approximately2800 years of their discovered Swasey pottery from Belize goes back to this time. common history. To understandthe reasonfor this it is Pottery is one of the most important types of evidence in necessaryto understandthat archaeologicalinformation is on- Mesoamericanarchaeology and the first appearanceof pottery ly partialinformation. Therefore, most archaeological informa- is always significant. Mesoamerica itself becomes known as a tion is subjectto morethan one interpretation.There is abun- culture area soon after the appearanceof pottery. dant evidencein Mesoamericanarchaeology supporting the Bookof Mormon,but in manycases a non-believercould offer Highpoint an opposinginterpretation to explainthe evidence.However, Archaeology necessarilydeals with physical things. Therefore the reconstructionof a long culturehistory is lesssubiect to in- an archaeologicalhighpoint is defined in terms of the quantity terpretationsince more data is gatheredto constructit than and quality of materialremains. Spiritual values of a culture are any other single type of archaeologicalevidence. This is much more difficult to detect. -

Architecture for Worship: Re-‐Thinking Sacred Space in The

Architecture for Worship: Re-Thinking Sacred Space in the Contemporary United States of America RICHARD S. VOSKO The purpose of this paper is to examine the symbolic value of religious buildings in the United States. It will focus particularly on places of worship and the theologies conveyed by them in an ever-changing socio-religious landscape. First, I will cite some of the emerging challenges that surface when thinking about conventional religious buildings. I will then describe those architectural "common denominators" that are important when re-thinking sacred space in a contemporary age. Churches, synagogues, and mosques exist primarily because of the convictions of the membership that built them. The foundations for these spaces are rooted in proud traditions and, sometimes, the idealistic hopes of each congregation. In a world that is seemingly embarked on a never-ending journey of war, poverty, and oppression these structures can be oases of peace, prosperity, and justice. They are, in this sense, potentially sacred spaces. The Search for the Sacred The search for the sacred is fraught with incredible distractions and challenges. The earth itself is an endangered species. Pollution is taken for granted. Rain forests are being depleted. Incurable diseases kill thousands daily. Millions have no pure water to drink. Some people are malnourished while others throw food away. Poverty and wealth live side by side, often in the same neighborhoods. Domestic abuse traumatizes family life. Nations are held captive by imperialistic regimes. And terrorism lurks everywhere. What do religious buildings, particularly places of worship, have to say about all of this? Where do homeless, hungry, abused, and stressed-out people find a sense of the sacred in their lives? One might even ask, where is God during this time of turmoil and inequity? By some estimates nine billion dollars were spent on the construction of religious buildings in the year 2000. -

Redalyc.Visiting a Hindu Temple: a Description of a Subjective

Ciencia Ergo Sum ISSN: 1405-0269 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México México Gil-García, J. Ramón; Vasavada, Triparna S. Visiting a Hindu Temple: A Description of a Subjective Experience and Some Preliminary Interpretations Ciencia Ergo Sum, vol. 13, núm. 1, marzo-junio, 2006, pp. 81-89 Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México Toluca, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=10413110 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Visiting a Hindu Temple: A Description of a Subjective Experience and Some Preliminary Interpretations J. Ramón Gil-García* y Triparna S. Vasavada** Recepción: 14 de julio de 2005 Aceptación: 8 de septiembre de 2005 * Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy, Visitando un Templo Hindú: una descripción de la experiencia subjetiva y algunas University at Albany, Universidad Estatal de interpretaciones preliminares Nueva York. Resumen. Académicos de diferentes disciplinas coinciden en que la cultura es un fenómeno Correo electrónico: [email protected] ** Estudiante del Doctorado en Administración complejo y su comprensión requiere de un análisis detallado. La complejidad inherente al y Políticas Públicas en el Rockefeller College of estudio de patrones culturales y otras estructuras sociales no se deriva de su rareza en la Public Affairs and Policy, University at Albany, sociedad. De hecho, están contenidas y representadas en eventos y artefactos de la vida cotidiana. -

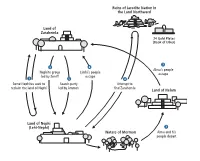

Land of Zarahemla Land of Nephi (Lehi-Nephi) Waters of Mormon

APPENDIX Overview of Journeys in Mosiah 7–24 1 Some Nephites seek to reclaim the land of Nephi. 4 Attempt to fi nd Zarahemla: Limhi sends a group to fi nd They fi ght amongst themselves, and the survivors return to Zarahemla and get help. The group discovers the ruins of Zarahemla. Zeniff is a part of this group. (See Omni 1:27–28 ; a destroyed nation and 24 gold plates. (See Mosiah 8:7–9 ; Mosiah 9:1–2 .) 21:25–27 .) 2 Nephite group led by Zeniff settles among the Lamanites 5 Search party led by Ammon journeys from Zarahemla to in the land of Nephi (see Omni 1:29–30 ; Mosiah 9:3–5 ). fi nd the descendants of those who had gone to the land of Nephi (see Mosiah 7:1–6 ; 21:22–24 ). After Zeniff died, his son Noah reigned in wickedness. Abinadi warned the people to repent. Alma obeyed Abinadi’s message 6 Limhi’s people escape from bondage and are led by Ammon and taught it to others near the Waters of Mormon. (See back to Zarahemla (see Mosiah 22:10–13 ). Mosiah 11–18 .) The Lamanites sent an army after Limhi and his people. After 3 Alma and his people depart from King Noah and travel becoming lost in the wilderness, the army discovered Alma to the land of Helam (see Mosiah 18:4–5, 32–35 ; 23:1–5, and his people in the land of Helam. The Lamanites brought 19–20 ). them into bondage. (See Mosiah 22–24 .) The Lamanites attacked Noah’s people in the land of Nephi. -

Conversion of Alma the Younger

Conversion of Alma the Younger Mosiah 27 I was in the darkest abyss; but now I behold the marvelous light of God. Mosiah 27:29 he first Alma mentioned in the Book of Mormon Before the angel left, he told Alma to remember was a priest of wicked King Noah who later the power of God and to quit trying to destroy the Tbecame a prophet and leader of the Church in Church (see Mosiah 27:16). Zarahemla after hearing the words of Abinadi. Many Alma the Younger and the four sons of Mosiah fell people believed his words and were baptized. But the to the earth. They knew that the angel was sent four sons of King Mosiah and the son of the prophet from God and that the power of God had caused the Alma, who was also called Alma, were unbelievers; ground to shake and tremble. Alma’s astonishment they persecuted those who believed in Christ and was so great that he could not speak, and he was so tried to destroy the Church through false teachings. weak that he could not move even his hands. The Many Church members were deceived by these sons of Mosiah carried him to his father. (See Mosiah teachings and led to sin because of the wickedness of 27:18–19.) Alma the Younger. (See Mosiah 27:1–10.) When Alma the Elder saw his son, he rejoiced As Alma and the sons of Mosiah continued to rebel because he knew what the Lord had done for him. against God, an angel of the Lord appeared to them, Alma and the other Church leaders fasted and speaking to them with a voice as loud as thunder, prayed for Alma the Younger.