A Few Faq's on Parliamentary Procedure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Principles

Parliamentary Principles . All delegates have equal rights, privileges and obligations . The majority vote decides. The rights of the minority must be protected. Full and free discussion of every proposition presented for decision is an established right of delegates. Every delegate has the right to know the meaning of the question before the assembly and what its effect will be. All meetings must be characterized by fairness and by good faith. Basic Rules of Motions 1. Motions have a definite order of precedence, each motion having a fixed rank for its introduction and consideration. 2. ONLY ONE MOTION MAY BE CONSIDERED AT A TIME. 3. No main motion can be substituted for another main motion EXCEPT that a new main motion on the same subject may be offered as a substitute amendment to the main motion. 4. All motions require a second to begin discussion unless it is from a delegation or committee or it is a simple request such as a question of privilege, a point of order or division. AMENDMENTS FOUR WAYS TO AMEND A MAIN MOTION 1. Amend by addition 2. Amend by deletion 3. Amend by addition and deletion 4. Amend by substitution TWO ORDERS OF AMENDMENTS 1. First order is an amendment to the original resolution 2. Second order is an amendment to the first order amendment. 3. No more than one order of amendment is discussed at the same time. Voting on Motions Majority vote: the calculation of the vote is based on the number of members present and voting or a majority of the legal votes cast ; abstentions are not counted; delegates who fail to vote are presumed to have waived the exercise of their right; applies to most motions Two-Thirds vote : a supermajority 2/3 vote is required when the vote restricts the right of full and free discussion: This includes a vote to TABLE, CLOSE DEBATE, LIMIT/EXTEND DEBATE, as well as to SUSPEND RULES. -

Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE

UNITED STATES Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE Effective for Meetings on or after February 1, 2021 Published November 19, 2020 ISS GOVERNANCE .COM © 2020 | Institutional Shareholder Services and/or its affiliates UNITED STATES PROXY VOTING GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Coverage ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Board of Directors ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Voting on Director Nominees in Uncontested Elections ........................................................................................... 8 Independence ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 ISS Classification of Directors – U.S. ................................................................................................................. 9 Composition ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Responsiveness ................................................................................................................................................... 12 Accountability .................................................................................................................................................... -

MASTER MUNICIPAL CLERK ACADEMY October 19-21, 2016 MCM Eleganté Hotel – Albuquerque

MASTER MUNICIPAL CLERK ACADEMY October 19-21, 2016 MCM Eleganté Hotel – Albuquerque TOTAL ACADEMY HOURS: 20 -PRELIMINARY PROGRAM- WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 19 7:30 am Registration 8:00 am – 5:15 pm PUBLIC SPEAKING FOR THE PUBLIC SERVANT Learn to write a speech that is powerful and delivers an effective result. Increase self-confidence, credibility and authority while delivering a clear message. Participants will have the opportunity to prepare and practice speech writing and delivery in a safe environment while learning skills they can use in all aspects of their life, from parenting to politicking. Learn the six principles of influence and persuasion used to create rapport, connection and move others towards a desired result. This is a “must attend” session for anyone that wishes to influence others in an ethical manner. What makes a good speech? What makes a good speaker? The components of a speech How to organize your information so that it makes sense! Writing an introduction How to introduce appropriately Good content for the body of your speech Body language Room set-up Selecting a topic Evaluating and analyzing the audience Deception and manipulation Ethics and truthfulness Using a microphone How to incorporate the 6 Principles of Influence and Persuasion into a speech and into daily life Close with power Instructor: Liz Walcher, Ph.D., CPT Organizational Consulting & Development Albuquerque, NM Mid-Morning & Mid-Afternoon Breaks 12:15 – 12:55 pm Lunch on Your Own THURSDAY, OCTOBER 20 8:00 am – 5:15 pm DEMOCRACY IN ACTION – PARLIAMENTARY PROCEDURE FOR GOVERNING BODY MEETINGS I. Parliamentary Procedure a. -

Motions Explained

MOTIONS EXPLAINED Adjournment: Suspension of proceedings to another time or place. To adjourn means to suspend until a later stated time or place. Recess: Bodies are released to reassemble at a later time. The members may leave the meeting room, but are expected to remain nearby. A recess may be simply to allow a break (e.g. for lunch) or it may be related to the meeting (e.g. to allow time for vote‐counting). Register Complaint: To raise a question of privilege that permits a request related to the rights and privileges of the assembly or any of its members to be brought up. Any time a member feels their ability to serve is being affected by some condition. Make Body Follow Agenda: A call for the orders of the day is a motion to require the body to conform to its agenda or order of business. Lay Aside Temporarily: A motion to lay the question on the table (often simply "table") or the motion to postpone consideration is a proposal to suspend consideration of a pending motion. Close Debate: A motion to the previous question (also known as calling for the question, calling the question, close debate and other terms) is a motion to end debate, and the moving of amendments, on any debatable or amendable motion and bring that motion to an immediate vote. Limit or extend debate: The motion to limit or extend limits of debate is used to modify the rules of debate. Postpone to a certain time: In parliamentary procedure, a postponing to a certain time or postponing to a time certain is an act of the deliberative assembly, generally implemented as a motion. -

Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2005 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Adrian Vermeule, "Absolute Voting Rules" (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 257, 2005). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 257 (2D SERIES) Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO August 2005 This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Chicago Working Paper Series Index: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=791724 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule* The theory of voting rules developed in law, political science, and economics typically compares simple majority rule with alternatives, such as various types of supermajority rules1 and submajority rules.2 There is another critical dimension to these questions, however. Consider the following puzzles: $ In the United States Congress, the votes of a majority of those present and voting are necessary to approve a law.3 In the legislatures of California and Minnesota,4 however, the votes of a majority of all elected members are required. -

A Guide to Parliamentary Procedure for New York City Community Boards

CITY OF NEW YORK MICHAEL R. BLOOMBERG, MAYOR A GUIDE TO PARLIAMENTARY PROCEDURE FOR NEW YORK CITY COMMUNITY BOARDS Mayor's Community Assistance Unit Patrick J. Brennan, Commissioner r. 2003/6.16.2006 Page 2 A Guide to Parliamentary Procedure for NYC Community Boards Mayor's Community Assistance Unit INTRODUCTION "The holding of assemblies of the elders, fighting men, or people of a tribe, community, or city to make decisions or render opinion on important matters is doubtless a custom older than history," notes Robert's Rules of Order, Newly Revised. This led to the need for rules of procedures to organize those assemblies. Throughout history, the writers of parliamentary procedure recognized that a membership meeting should be a place where different people of a community gather to debate openly and resolve issues of common concerns, the importance of conducting meetings in a democratic manner, and the need to protect the rights of individuals, groups, and the entire assembly. Parliamentary procedure originally referred to the customs and rules used by the English Parliament to conduct its meetings and to dispose of its issues. Some of the unusual terms used today attest to that connection -- such terms as "Lay On The Table" or "I Call The Previous Question." In America, General Henry Martyn Robert (1837-1923), a U.S. Army engineering officer was active in civic and educational works and church organizations. After presiding over a meeting, he wrote "But with the plunge went the determination that I would never attend another meeting until I knew something of... parliamentary law." After many years of study and work, the first edition of Robert's manual was published on February 19, 1876 under the title, Robert's Rules of Order. -

Rules of Order

DEPARTMENT OF TRAINING RULES OF ORDER A SIMPLIFIED GUIDE TO PARLIAMENTARY PROCUDURE ADOPTED FOR USE BY THE AUXILIARY Rev. (10/06) INTRODUCTION Any business meeting of the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, whether it is a meeting of a flotilla, or a division, District or National Board, must proceed in an orderly way if it is to bring satisfactory results. There are certain widely accepted rules of conducting such meetings. These “Rules of Order” are a part of that large body or practices which are grouped under the term “parliamentary procedure.” Besides making for orderliness of procedure, parliamentary rules are intended to protect the rights of the individual participant and of minorities at a meeting. At the same time, they are also intended to enable the majority to get things accomplished without reasonable delay. The parliamentary rules of particular importance are easy to understand. For purposes of clarity, the “Presiding Officer” could be the Flotilla Commander, Division Captain or District Commodore. When “Board” is mentioned, this would be synonymous with the voting members of the body. STANDING RULES AND BYLAWS Standing rules are required for Auxiliary Districts and National Boards. Flotilla and divisions may have standing rules if desired or required by district policy. Standing rules normally provide for, and include such matters as meetings, voting, finances, awards, duties of officers, and provisions for amendments and additions. Standing rules shall not conflict with the provisions of the Auxiliary Manual, COMDTINST M16790.1 (Series), or other directives of the Coast Guard or the standing rules of the Auxiliary National Board or other senior Auxiliary units. -

1- Rules of the House of Representatives 1.0 Procedural and Parliamentary Authority 1-1 Manual. the Wyoming Manual of Legisla

Rules of the House of Representatives 1.0 Procedural and Parliamentary Authority 1-1 Manual. The Wyoming Manual of Legislative Procedures, Revised, shall be referred to as the "Manual." 1-2 Parliamentary Practice. The rules of parliamentary practice comprised in Mason's Manual of Legislative Procedure shall govern the House in all cases to which they can apply and in which they are not inconsistent with the rules and orders of the House and Joint Rules. [Ref: Mason's §§ 30 to 32] 1-3 Suspension of Rules. No change, suspension, or addition to the rules of the house shall be made except by a two-thirds vote of the elected members. [Ref: Mason's §§ 279 to 287] 2.0 House Organization 2-1 Removal of Officers. A vote of at least two-thirds of the elected House members for the removal of any officer of the House shall be sufficient to vacate the chair or office. [Ref: Mason's § 581] 2-2 House Committees. The Speaker of the House after conferring with the majority and minority leaders shall appoint members to House standing committees subject to House Rule 2-3. House standing committees are as follows: 1. Judiciary 2. Appropriations 3. Revenue 4. Education 5. Agriculture, State and Public Lands and Water Resources 6. Travel, Recreation, Wildlife and Cultural Resources 7. Corporations, Elections and Political Subdivisions 8. Transportation, Highways and Military Affairs 9. Minerals, Business and Economic Development 10. Labor, Health and Social Services 11. Journal 12. Rules and Procedure [Ref: Mason's §§ 600 to 602] -1- 2-3 Committee Membership. -

Myths and Half Truths Concerning Parliamentary Procedure: Bet You Have Heard Some of These!

Myths and Half truths concerning parliamentary procedure: Bet you have heard some of these! Commentary on each: 1. Exofficio members never have right to vote. The term exoffico simply means “by virtue of”. That is, some groups may have the president or vice president as a member of any or all committees; the county agent may be listed as “exoffico” member of the Extension Board; the student body president may be an exoffico member of the community foundation, etc. The State Fair board has an exoffico spot listed for the governor and others. Whether the person filling this spot has voting rights maybe spelled out in the group’s governing documents. The default according to RONR would be that they would have full rights while serving on the board—that is, right to present motion, debate, and vote. Many groups because of either provisions in their governing documents or custom to not allow for full rights (often this is because of the misconception of rights of exoffico). 2. Executive Committee can always over ride decision of whole assembly. The default is that nobody (officer or officers or executive committee) can over ride the will of the assembly. So any such authority must be found other than in their parliamentary authority. On the other hand commonsense says it may be necessary—for example: the body at their annual convention voted to hold the next annual convention on the same corresponding date AND at the same location. Due to other circumstances it is later found that either the date will not work at that site or that site will not be available— so a decision will have to be made by the executive committee (or other designated committee). -

Postpone, Motion To

POSTPONE, MOTION TO Under Rule XXII the motions "to postpone indefinitely," or "to postpone to a day certain," are privileged after the motion to lay on the table, and take precedence over motions to commit or refer, as well as over any amendments offered. Both motions are debatable and a motion to postpone in definitely for all practical purposes, when agreed to, is deemed to be a final disposition of the particular proposition so post poned. A motion to postpone action on a matter to a day certain anticipates further action on that date; for example, if the Senate should be considering a bill and moved to postpone further con sideration of that bill until a specific day, when that day arrives it would be assumed that the Senate would return to its consid eration. Rule XXII, Paragraph 1 [Precedence of Motions] When a question is pending, no motion shall be received but:--, To adjourn. To adjourn to a day certain, or that when the Senate adjourn it shall be to a day certain. To take a recess. To proceed to the consideration of executive business. To lay on the table. To postpone indefinitely. To postpone to a day certain. To commit. To amend. Which several motions shall have precedence as they stand arranged; and the motions relating to adjournment, to take a recess, to proceed to the consideration of executive business, to lay on the table, shall be decided without debate. Amendments Between Houses: See "Postpone," pp. 140-141. Amendments to Bill: A motion to postpone an amendment to a day certain, or to postpone indefinitely, is in order under Rule XXII; 1 I Sept. -

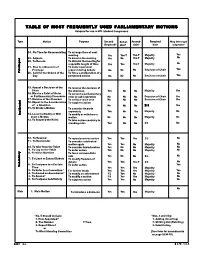

Table of Most Freq Table of Most Frequently Used Parliament Y

TABLE OF MOST FREQUENTLY USED PARLIAMENTARY MOTIONS Adapted for use in NFL Student Congresses Type Motion Purpose Second Debat- Amend- Required May Interrupt Required? able? able? Vote a Speaker 24. Fix Time for Reassembling To arrange time of next meeting Yes Yes-T Yes-T Majority Yes 23. Adjourn To dismiss the meeting Yes No Yes-T Majority No 22. To Recess To dismiss the meeting for a specific length of time Yes Yes Yes-T Majority No 21. Rise to a Question of To make a personal Privilege request during debate No No No Decision of Chair Yes Privileged Privileged Privileged Privileged Privileged 20. Call for the Orders of the To force consideration of a Day postponed motion No No No Decision of Chair Yes 19. Appeal a Decision of the To reverse the decision of Chair the chairman Yes No No Majority Yes 18. Rise to a Point of Order To correct a parliamentary or Parliamentar y Procedure error or ask a question No No No Decision of Chair Yes 17. Division of the Chamber To verify a voice vote No No No Decision of Chair Yes 16. Object to the Consideration To suppress action of a Question No No No 2/3 Yes 15. To Divide a Motion To consider its parts separately Yes No Yes Majority No Incidental Incidental Incidental Incidental Incidental 14. Leave to Modify or With To modify or withdraw a draw a Motion motion No No No Majority No 13. To Suspend the Rules To take action contrary to standing rules Yes No No 2/3 No 12. -

Parliamentary Procedure for Counties a GUIDE and MODEL ORDINANCE Copyright 2016, ACCG

8TH EDITION Parliamentary Procedure for Counties A GUIDE AND MODEL ORDINANCE Copyright 2016, ACCG. ACCG serves as the consensus building, training, and legislative organization for all 159 county governments in Georgia. For more information, visit: accg.org. DISCLAIMER: This publication contains general information for the use of the members of ACCG and the public. This information is not and should not be considered legal advice. Readers should consult with legal counsel before taking action based on the information contained in this handbook. PARLIAMENTARY PROCEDURE 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 4 DEFINITIONS ............................................................................................................ 5 THE ROLES OF THE BOARD AND MEETING PARTICIPANTS ........................................ 6 Chair .................................................................................................................. 6 District Commissioners ......................................................................................... 6 County Clerk ....................................................................................................... 6 County Attorney ................................................................................................... 6 County Manager, Administrator, and Department Heads ........................................... 6 Invited Speakers .................................................................................................