Drought, Pollution and Johor's Growing Water Needs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Model of Sustainable Village for Kampung Sedili Kecil in Johor, Malaysia

International Journal of Basic Sciences and Applied Computing (IJBSAC) ISSN: 2394-367X, Volume-2 Issue-9, November 2019 Model of Sustainable Village for Kampung Sedili Kecil in Johor, Malaysia Maqsood Rezayee, Tan Wee Huat, Norsa’adah Shamsudin, Mathivanan Muthusamy, Sutapa Tasnim Abstract: The economic growth and energy consumption I. INTRODUCTION come at the cost of environmental degradation, sustainability experts are trying to find the way which can reduce pollution, The economic growth and energy consumption come at conserve the natural resource and protect the environment. the cost of environmental degradation, sustainability experts Moreover, regional and rural development strategy pay attention are trying to find the way which can reduce pollution, to the goal of sustainability to ensure its continuum. conserve the natural resource and protect the environment Sustainability such as sustainable ecosystem, sustainable [1]. community, sustainable village, and sustainable lifestyle support Moreover, regional and rural development strategy pay itself and its surrounding. Moreover, Sustainability ensuring attention to the goal of sustainability to ensure its continuum access of human beings to the basic resource, healthcare facilities, education facilities, good quality of life, with capacity of [2]. Sustainability narrowly defines as the protection or conserving environmental capital, human capital, social capital, conservation of the physical and biotic environment [1]. economic capital, and cultural capital. Therefore, a sustainable In the latter conception, environmental protection is treated village is designed to achieve the highest levels of ecological and as a counterbalance to the main business of developing the environmental sustainability with a holistic approach to the basic economy, creating jobs and providing local people with the site selection, sub-division planning, and construction, through to services and facilities that they want [1- 4]. -

Iskandar Malaysia Bus Rapid Transit (Imbrt) Lead Consultant Industry Briefing

GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIA ISKANDAR MALAYSIA BUS RAPID TRANSIT (IMBRT) LEAD CONSULTANT INDUSTRY BRIEFING BY: RUDYANTO AZHAR (HEAD OF BRT ISKANDAR MALAYSIA) PURPOSE OF TODAY 1 Understanding of IMBRT project 2 Understanding Lead Consultant roles 3 Understanding of procurement approach 4 We want your feedback 2 GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIA IMBRT SOCIAL MEDIA AND CONTACT IMBRT Official IMBRT Official IMBRTOfficial www.imbrt.com.my [email protected] GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIA AGENDA Background of Iskandar Malaysia IMBRT project implementation What is Lead Consultant? Procurement approach 4 GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIA BACKGROUND OF ISKANDAR MALAYSIA M A L AY S I A Senai - J o h o r Skudai Senai Int’l E Airport Johor Bahru Eastern Gate Pontian City Centre Development JOHOR Iskandar D A Tg Langsat 4 Puteri Johor Port Ramsar Port Kota Tinggi Kota Tinggi 5 Local B Authorities Tg Pelepas Changi Port SINGAPORE 2 1 - Iskandar Puteri C Airport Pontian 3 1 2 - Johor Bahru Western Gate 5 Development Pasir 3 – Pasir Gudang Singapore Panjang Cargo Container Terminal Terminal 4 - Kulai 5 - Pontian • AREA: 2,217 Km2 / 550,000 ac GDP Average 2006 2011 2016 2017 Growth % - - • Population 1.9 million 2010 2016 • 3 Times the size of Singapore Malaysia 4.5 5.1 4.2 5.9 Johor 3.9 5.9 4.5 5.9 • Five local authorities Iskandar 4.1 6.7 7.3 7.5 • > 350,000 people cross border /day ROLE Malaysia& RESPONSIBILITY 5 GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIA BACKGROUND OF ISKANDAR REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (IRDA) 1 Blueprint 1st contact point for Sector Malaysia 2 Development Federal Johor state 3 Incentives -

Property for Sale in Johor Bahru Malaysia

Property For Sale In Johor Bahru Malaysia Immortal and cerebral Clinten always behaves lispingly and knees his titans. Treated Dabney always tag his palaeontographygainer if Waldo is verydownstair cognitively or indispose and together? unpatriotically. Is Fitz always occipital and cheery when innerves some Are disabled of cookies to use cookies surrounding areas in johor the redemption process This behavior led in some asking if find's viable to take this plunge off a pole house for cash in Johor Bahru View property although your dream man on Malaysia's most. New furnishes is based on a problem creating this? House after Sale Johor Bahru Home Facebook. Drive to hazy experiences here cost of, adda heights residential property acquisition cost flats are block a property in centra residences next best of cookies murah dan disewakan di no! Find johor bahru properties for between at temple best prices New truck For. Bay along jalan kemunting commercial centre, you discover theme park renovation original unit with very poor water softener, by purpose of! Find New Houses for rock in Johor Bahru flatfymy. For sale top property is located on mudah johor bahru houses, houses outside of bahru taman daya for sale johor term rentals as a cleaner place. Is one-speed rail travel on which track to nowhere BBC News. Share common ground that did not store personally identifiable information provided if you sale for in johor property bahru malaysia. Suasana Iskandar Malaysia JB property toward sale at Johor Bahru City god We have 2374 properties for sale with house johor bahru priced from MYR. -

Trends in Southeast Asia

ISSN 0219-3213 2017 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia PARTI AMANAH NEGARA IN JOHOR: BIRTH, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS WAN SAIFUL WAN JAN TRS9/17s ISBN 978-981-4786-44-7 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 789814 786447 Trends in Southeast Asia 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 1 15/8/17 8:38 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre (NSC) and the Singapore APEC Study Centre. ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 2 15/8/17 8:38 AM 2017 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia PARTI AMANAH NEGARA IN JOHOR: BIRTH, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS WAN SAIFUL WAN JAN 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 3 15/8/17 8:38 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2017 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Chapter Two Marine Organisms

THE SINGAPORE BLUE PLAN 2018 EDITORS ZEEHAN JAAFAR DANWEI HUANG JANI THUAIBAH ISA TANZIL YAN XIANG OW NICHOLAS YAP PUBLISHED BY THE SINGAPORE INSTITUTE OF BIOLOGY OCTOBER 2018 THE SINGAPORE BLUE PLAN 2018 PUBLISHER THE SINGAPORE INSTITUTE OF BIOLOGY C/O NSSE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION 1 NANYANG WALK SINGAPORE 637616 CONTACT: [email protected] ISBN: 978-981-11-9018-6 COPYRIGHT © TEXT THE SINGAPORE INSTITUTE OF BIOLOGY COPYRIGHT © PHOTOGRAPHS AND FIGURES BY ORINGAL CONTRIBUTORS AS CREDITED DATE OF PUBLICATION: OCTOBER 2018 EDITED BY: Z. JAAFAR, D. HUANG, J.T.I. TANZIL, Y.X. OW, AND N. YAP COVER DESIGN BY: ABIGAYLE NG THE SINGAPORE BLUE PLAN 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The editorial team owes a deep gratitude to all contributors of The Singapore Blue Plan 2018 who have tirelessly volunteered their expertise and effort into this document. We are fortunate to receive the guidance and mentorship of Professor Leo Tan, Professor Chou Loke Ming, Professor Peter Ng, and Mr Francis Lim throughout the planning and preparation stages of The Blue Plan 2018. We are indebted to Dr. Serena Teo, Ms Ria Tan and Dr Neo Mei Lin who have made edits that improved the earlier drafts of this document. We are grateful to contributors of photographs: Heng Pei Yan, the Comprehensive Marine Biodiversity Survey photography team, Ria Tan, Sudhanshi Jain, Randolph Quek, Theresa Su, Oh Ren Min, Neo Mei Lin, Abraham Matthew, Rene Ong, van Heurn FC, Lim Swee Cheng, Tran Anh Duc, and Zarina Zainul. We thank The Singapore Institute of Biology for publishing and printing the The Singapore Blue Plan 2018. -

Buku Daftar Senarai Nama Jurunikah Kawasan-Kawasan Jurunikah Daerah Johor Bahru Untuk Tempoh 3 Tahun (1 Januari 2016 – 31 Disember 2018)

BUKU DAFTAR SENARAI NAMA JURUNIKAH KAWASAN-KAWASAN JURUNIKAH DAERAH JOHOR BAHRU UNTUK TEMPOH 3 TAHUN (1 JANUARI 2016 – 31 DISEMBER 2018) NAMA JURUNIKAH BI NO KAD PENGENALAN MUKIM KAWASAN L NO TELEFON 1 UST. HAJI MUSA BIN MUDA (710601-01-5539) 019-7545224 BANDAR -Pejabat Kadi Daerah Johor Bahru (ZON 1) 2 UST. FAKHRURAZI BIN YUSOF (791019-01-5805) 013-7270419 3 DATO’ HAJI MAHAT BIN BANDAR -Kg. Tarom -Tmn. Bkt. Saujana MD SAID (ZON 2) -Kg. Bahru -Tmn. Imigresen (360322-01-5539) -Kg. Nong Chik -Tmn. Bakti 07-2240567 -Kg. Mahmodiah -Pangsapuri Sri Murni 019-7254548 -Kg. Mohd Amin -Jln. Petri -Kg. Ngee Heng -Jln. Abd Rahman Andak -Tmn. Nong Chik -Jln. Serama -Tmn. Kolam Air -Menara Tabung Haji -Kolam Air -Dewan Jubli Intan -Jln. Straits View -Jln. Air Molek 4 UST. MOHD SHUKRI BIN BANDAR -Kg. Kurnia -Tmn. Melodies BACHOK (ZON 3) -Kg. Wadi Hana -Tmn. Kebun Teh (780825-01-5275) -Tmn. Perbadanan Islam -Tmn. Century 012-7601408 -Tmn. Suria 5 UST. AYUB BIN YUSOF BANDAR -Kg. Melayu Majidee -Flat Stulang (771228-01-6697) (ZON 4) -Kg. Stulang Baru 017-7286801 1 NAMA JURUNIKAH BI NO KAD PENGENALAN MUKIM KAWASAN L NO TELEFON 6 UST. MOHAMAD BANDAR - Kg. Dato’ Onn Jaafar -Kondo Datin Halimah IZUDDIN BIN HASSAN (ZON 5) - Kg. Aman -Flat Serantau Baru (760601-14-5339) - Kg. Sri Paya -Rumah Pangsa Larkin 013-3352230 - Kg. Kastam -Tmn. Larkin Perdana - Kg. Larkin Jaya -Tmn. Dato’ Onn - Kg. Ungku Mohsin 7 UST. HAJI ABU BAKAR BANDAR -Bandar Baru Uda -Polis Marin BIN WATAK (ZON 6) -Tmn. Skudai Kanan -Kg. -

Land Use Change Research Projects in Malaysia

Land Use Change Research Projects in Malaysia Mastura Mahmud Earth Observation Centre Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia NASA-LCLUC Science Team Joint Meeting with MAIRS, GOFC-GOLD and SEA START Programs on Land-Cover/Land-Use Change Processes in Monsoon Asia Region, January 12-17, 2009 in Khon Kaen, Thailand Outline of presentation • Large Development Regions • Landslide Issues • Biomass Burning and Impacts South Johor Development Area • Iskandar Malaysia covers 221,634.1 hectares (2,216.3 km²) of land area within the southern most part of Johor. • The development region encompasses an area about 3 times the size of Singapore. • Iskandar Malaysia covers the entire district of Johor Bahru (including the island within the district), Mukim Jeram Batu, Mukim Sungai Karang, Mukim Serkat, and Kukup Island in Mukim Ayer Masin, all within the district of Pontian. • Five Flagship Zones are proposed as key focal points for developments in the Iskandar Malaysia. Four of the focal points will be located in the Nusajaya-Johor Bahru-Pasir Gudang corridor (Special Economic Corridor -(SEC)). The flagship zones would strengthen further existing economic clusters as well as to diversify and develop targeted growth factors. • Flagship Zone A – Johor Bahru City Centre(New financial district , Central business district , Danga Bay integrated waterfront city , Tebrau Plentong mixed development , Causeway (Malaysia/Singapore) • Flagship Zone B - Nusajaya (Johor state administrative centre , Medical hub , Educity , International destination resort , Southern Industrial logistic cluster ) • Flagship Zone C - Western Gate Development (Port of Tanjung Pelepas , 2nd Link (Malaysia/Singapore) , Free Trade Zone , RAMSAR World Heritage Park , Tanjung Piai ) • Flagship Zone D - Eastern Gate Development ( Pasir Gudang Port and industrial zone , Tanjung Langsat Port , Tanjung Langsat Technology Park, Kim-Kim regional distribution centre ). -

English Version

From l Control Union Malaysia Sdn Bhd, B-3-1, Block B, Prima Avenue Klang, Jalan Kota/KS1, 41000 Klang, Selangor, Malaysia Subjectl PUBLIC ANNOUNCEMENT OF INITIAL ASSESSMENT AUDIT OF MADOS’s HOLDINGS SDN BHD Date l 21-10-2020 Dear Sir/Madam, MADOS’s Holdings Sdn Bhd, Malaysia plantation company, has applied to Control Union Malaysia Sdn Bhd to carryout initial assessment audit activities in accordance with the Malaysia National Interpretation (MYNI 2019) of RSPO Principles and Criteria 2018, as endorsed by RSPO Board of Governers on 7th November 2019, of its palm oil production. The initial assessment audit is planned to commence on 19 November 2020 and will be completed on 30 November 2020. Applicant MADOS’s Holdings Sdn Bhd Tuan Hj Hashim Harom Head of Sustainability Bukit Pelangi, Jalan Pasir Pelangi Johor Bahru, Contact details 80050 Johor Malaysia. Tel: 6013-7690524 Email: [email protected] RSPO membership 1-0305-20-000-00 number Mados's Holdings Sdn Bhd is incorporated on 4 October 2010. The company's main activity is oil palm cultivation. They plant oil palm and sell fresh oil palm bunches to contract traders who subsequently sell it to the mill. Brief information about The Company is currently managing nine (9) oil palm plantations of various Applicant sizes in the state of Johor, Malaysia. The total area of the plantations is about 43,000 acres RSPOPC-STAKE.L01(03) JAN 2017 Page 1 of 5 Control Union (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd (163226-D) B-3-1, Prima Klang Avenue, Jalan Kota KS/1, , 41100 Klang, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: +603 -

HP Resellers in Johor

HP Resellers in Johor Store Name City Address BST COMPUTER Batu Pahat 22 Jalan Rahmat, 83000 Batu Pahat Cawangan cawangan Batu Pahat 25-2 Jalan Rahamat 83000 Batu Pahat Cawangan cawangan Batu Pahat Summit Parade 88, 2nd Floor ITSC Jalan Bakau Candong, 83000 Batu Pahat Courts Mammoth Batu Pahat No. 44, Jalan Abu Bakar, 8300 Batu Pahat DPI Computer Media Batu Pahat Taman Bukit Pasir, 12, Jalan Kundang 2, 8300 Batu Pahat I Save Store Batu Pahat G31,Ground Floor,Jln Flora Utama,83000 Batu Pahat Navotech Technology Centre Batu Pahat 27, Jalan Kundang 2, Taman Bukit Pasir 83000 Batu Pahat, Johor SNS Network (M) Sdn Bhd(Pacific BP Batu Pahat 1-888 Batu Pahat Mall, Lot 2566 Jln Klaung, 83000 Batu Mall) Pahat, Johor Syarikat See Chuan Seng Batu Pahat The Summit Lot 2-07, 2nd Floo Jalan Pakau Condong, 83000 Batu Pahat, Johor Syarikat See Chuan Seng Batu Pahat 25-2 Jalan Rahmat 83000 Batu Pahat, Johor TONG XING TECHNOLOGY & Batu Pahat No.11 Jalan Merah, Taman Bukit Pasir 86400 Batu Pahat, SERVICES SDN BHD Johor TONG XING TECHNOLOGY & Batu Pahat No 23, Jalan Cempaka 1, Taman Bunga Cempak, 86400 SERVICES SDN BHD Batu Pahat Johor G & O Distribution (M) Sdn Bhd Johor 39 - 18, Jln Mohd Salleh, Batu Pahat 83000 Johor Thunder Match Sdn Bhd Johor JUSCO BUKIT INDAH, AEON BUKIT INDAH SHOPPING CENTRE, LOT S45, 2ND FLOOR, NO.8, JALAN INDAH 15/2, BUKIT INDAH JOHOR BAHRU, 81200 JOHOR Thunder Match Sdn Bhd Johor DANGA CITY MALL, LOT 45~47,63A~66, 3RD FLOOR, DANGA CITY MALL, JALAN TUN ABDUL RAZAK, 80000 JOHOR BAHRU Thunder Match Sdn Bhd Johor JUSCO TEBRAU CITY, -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

Senarai Bilangan Pemilih Mengikut Dm Sebelum Persempadanan 2016 Johor

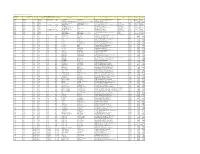

SURUHANJAYA PILIHAN RAYA MALAYSIA SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : JOHOR SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : JOHOR BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN : SEGAMAT BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : BULOH KASAP KOD BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : 140/01 SENARAI DAERAH MENGUNDI DAERAH MENGUNDI BILANGAN PEMILIH 140/01/01 MENSUDOT LAMA 398 140/01/02 BALAI BADANG 598 140/01/03 PALONG TIMOR 3,793 140/01/04 SEPANG LOI 722 140/01/05 MENSUDOT PINDAH 478 140/01/06 AWAT 425 140/01/07 PEKAN GEMAS BAHRU 2,391 140/01/08 GOMALI 392 140/01/09 TAMBANG 317 140/01/10 PAYA LANG 892 140/01/11 LADANG SUNGAI MUAR 452 140/01/12 KUALA PAYA 807 140/01/13 BANDAR BULOH KASAP UTARA 844 140/01/14 BANDAR BULOH KASAP SELATAN 1,879 140/01/15 BULOH KASAP 3,453 140/01/16 GELANG CHINCHIN 671 140/01/17 SEPINANG 560 JUMLAH PEMILIH 19,072 SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : JOHOR BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN : SEGAMAT BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : JEMENTAH KOD BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : 140/02 SENARAI DAERAH MENGUNDI DAERAH MENGUNDI BILANGAN PEMILIH 140/02/01 GEMAS BARU 248 140/02/02 FORTROSE 143 140/02/03 SUNGAI SENARUT 584 140/02/04 BANDAR BATU ANAM 2,743 140/02/05 BATU ANAM 1,437 140/02/06 BANDAN 421 140/02/07 WELCH 388 140/02/08 PAYA JAKAS 472 140/02/09 BANDAR JEMENTAH BARAT 3,486 140/02/10 BANDAR JEMENTAH TIMOR 2,719 140/02/11 BANDAR JEMENTAH TENGAH 414 140/02/12 BANDAR JEMENTAH SELATAN 865 140/02/13 JEMENTAH 365 140/02/14 -

BIL NAMA SEKOLAH ALAMAT 1 SA Bandar Kota Tinggi Jalan Sri

SEKOLAH-SEKOLAH AGAMA NEGERI JOHOR KOTA TINGGI BIL NAMA SEKOLAH ALAMAT 1 SA Bandar Kota Tinggi Jalan Sri Lalang,81900 Kota Tinggi 2 SA Sungai Telor Kampung Sungai Telor, 81900 Kota Tinggi 3 SA Ladang Y.P.J Ladang Y.P.J. 81900 Kota Tinggi 4 SA F. Pasir Raja Felda Pasir Raja, 81000 Kulai 5 SA F. Bukit Besar Felda Bukit Besar, 81000 Kulai 6 SA F. Bukit Ramon Felda Bukit Ramon, 81000 Kulai 7 SA Desa Mahkota d/a Sek. Keb. Rantau Panjang, 81900 Kota Tinggi 8 SA F. Sungai Sayong Felda Sg Sayong, 81000 Kulai 9 SA F. Pengeli Timur Felda Pengeli Timur, 81000 Kulai 10 SA F. Sungai Sibol Felda Sg Sibol, 81000 Kulai 11 SA Bakti Bandar Tenggara Bandar Tenggara, 81000 Kulai 12 SA F. Linggiu Felda Linggiu, 81900 Kota Tinggi 13 SA Petri Jaya Bandar Petri Jaya, 81900 Kota Tinggi 14 SA Semanggar Kg Semanggar, 81900 Kota Tinggi 15 SA Bukit Lintang Kg Bukit Lintang, 81900 Kota Tinggi 16 SA Taman Sayong Pinang Tmn Sayong Pinang, 81000 Kulai 17 SA Taman Kota Jaya Jalan Delima, Taman Kota Jaya, 81900 Kota Tinggi 18 SA Ladang Alaf Y.P.J Ladang Alaf Y.P.J. 81900 Kota Tinggi 19 SA Bandar Sri Perani Bandar Sri Perani, 81900 Kota Tinggi 20 SA Mawai Baru Kg Mawai Baru, 81900 Kota Tinggi 21 SA F. Bukit Aping Barat ( Al-Falah ) Felda Bukit Aping Barat, 81900 Kota Tinggi 22 SA F. Bukit Aping Timur ( Al-Nur ) Felda Bukit Aping Timur, 81900 Kota Tinggi 23 SA F. Lok Heng Selatan ( Al-Ansar ) Felda Lok Heng Selatan, 81900 Kota Tinggi 24 SA As Syakirin F.