Peripheral Arterial Disease and Isolated Systolic Hypertension: the ATTEST Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypertension – Adult – Clinical Practice Guideline

Hypertension – Adult – Clinical Practice Guideline Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 3 SCOPE ...................................................................................................................................... 4 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................................................................................. 5 Establish the Diagnosis ........................................................................................... 5 Patient Evaluation ................................................................................................... 7 Treatment Goals ..................................................................................................... 7 Lifestyle Modifications ............................................................................................. 8 Table 4 – Lifestyle Modifications ........................................................................ 9 Medication Treatment............................................................................................ 11 Figure 1 - Initiation and Titration of Antihypertensive Medication ..................... 13 Table 7 - Antihypertensive -

High B1a0d Pressure and Its Treatment in General

HIGH B1A0D PRESSURE AND ITS TREATMENT IN GENERAL PRACTICE WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO A SERIES OF 100 CASES TREATED BY THE AUTHOR By HAROLD WILSON B01YBR IB.ffh.B. ProQuest Number: 13849841 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13849841 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 -CONTENTS SECTION 1. Introduction. SECTION 2. General Remarks. Definitions of General Interest. Present Views on Etiology. Pathology and Morbid Anatomy. Brief Historical Survey. SECTION 3. The Present Position. Prevalence. Clinical Manifestations. Prognosis. SECTION 4. Prevalence in Bolton. Summary of Cases. Symptomatology and Case Histories Prognosis. Treatment. SECTION 5. Conclusions. Bibliography. SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION. I think it can truthfully be said that the most interest ing problems in Medioine are those that are most baffling. Some years ago Ralph M a j o r ^ wrote these words, ”If our knowledge of the etiology of arterial hypertension is shrouded in a oertain haze, our knowledge of an effective therapy in this disease is enveloped in a dense fog.n A study of some of the vast literature on this subject does not greatly clarify the obscurity. -

441.2.Full.Pdf

Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.4790 on 12 June 2018. Downloaded from Scientific Abstracts Thursday, 14 June 2018 441 All GCA TAK p (n 23) (n 13) (n 8) Female, n (%) 19 (82.6) 12 (92.3) 6 (75) ns Age at diagnosis 63 (51–68) 68 (63–73) 43.5 (30.5–57) 0.003 Diagnostic latency (months) 4.5 (2–12) 3 (2–10) 8 (3.5–12) ns ESR at disease onset (mm/h) 49 (38–68) 52.5 (45.5– 42 (40–61.5) ns 59.7) CRP at disease onset (mg/L) 61.8 (13– 89 (32.5–106) 60.5 (9.3–132.5) ns 132.5) Disease duration at PET/MR 27 (18–36) 24 (13–29.5) 36.5 (14.75– ns (months) 129.3) ESR at examination (mm/h) 18 (9–35) 16 (7–31) 20.5 (11–44.5) ns CRP at examination (mg/L) 4.5 (2.55–8.9) 3.9 (3.48–4.72) 4.55 (2.05–10.4) ns Results: 23 LVV patients were included, 56.5% GCA, 34.8% TAK and 8.7% iso- Results: Among 602 patients with TA during this period, 119 (19.8%) were jTA, lated aortitis, all Caucasian, mostly females (82%). We considered 55 PET scans, while 483 were aTA. Female predominance was less striking in jTA (71.4%) than 32/55 in LVV group (from min. 1 to max. 3 scans/patient) mainly during follow-up aTA (79%), p=0.047. Patients with jTA had presented more commonly with fever (29/32 scans), and 23/55 in control group. -

Echocardiography in Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension

REVIEW ARTICLE published: 12 November 2014 PEDIATRICS doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00124 Echocardiography in pediatric pulmonary hypertension Pei-Ni Jone* and D. Dunbar Ivy Pediatric Cardiology, Children’s Hospital Colorado, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA Edited by: Pulmonary hypertension (PH) can be a rapidly progressive and fatal disease. Although Antonio Francesco Corno, Universiti right heart catheterization remains the gold standard in evaluation of PH, echocardiogra- Sains Malaysia, Malaysia phy remains an important tool in screening, diagnosing, evaluating, and following these Reviewed by: Jeffrey Feinstein, Stanford University, patients. In this article, we will review the important echocardiographic parameters of the USA right heart in evaluating its anatomy, hemodynamic assessment, systolic, and diastolic Cecile Tissot, The University function in children with PH. Children’s Hospital, Switzerland Tilman Humpl, SickKids Hospital, Keywords: pediatric pulmonary hypertension, echocardiography, right heart, right ventricular function Canada *Correspondence: Pei-Ni Jone, Pediatric Cardiology, Children’s Hospital Colorado, University of Colorado School of Medicine, 13123 East 16th Avenue, B100, Aurora, CO 80045, USA e-mail: pei-ni.jone@ childrenscolorado.org INTRODUCTION of the RA area in end-systole is performed to evaluate for RA dila- Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a progressive disease that carries tion (Figure 1)(3). Indexed RA area to body surface area in adult high morbidity and mortality. Although cardiac catheterization is patients with idiopathic PH has been a predictor of mortality and used to define PH, echocardiography is the most important non- has been shown to be a prognostic marker for follow up of PH invasive tool that is used to detect PH (1). -

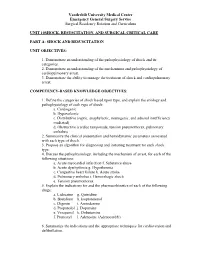

Unit 10 Shock,Resuscitation Part A

Vanderbilt University Medical Center Emergency General Surgery Service Surgical Residency Rotation and Curriculum UNIT 10SHOCK, RESUSCITATION, AND SURGICAL CRITICAL CARE PART A: SHOCK AND RESUSCITATION UNIT OBJECTIVES: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the pathophysiology of shock and its categories. 2. Demonstrate an understanding of the mechanisms and pathophysiology of cardiopulmonary arrest. 3. Demonstrate the ability to manage the treatment of shock and cardiopulmonary arrest. COMPETENCY-BASED KNOWLEDGE OBJECTIVES: 1. Define the categories of shock based upon type, and explain the etiology and pathophysiology of each type of shock: a. Cardiogenic b. Hypovolemic c. Distributive (septic, anaphylactic, neurogenic, and adrenal insufficiency mediated) d. Obstructive (cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, pulmonary embolus) 2. Summarize the clinical presentation and hemodynamic parameters associated with each type of shock. 3. Propose an algorithm for diagnosing and initiating treatment for each shock type. 4. Discuss the pathophysiology, including the mechanism of arrest, for each of the following situations: a. Acute myocardial infarction f. Substance abuse b. Acute dysrhythmia g. Hypothermia c. Congestive heart failure h. Acute stroke d. Pulmonary embolus i. Hemorrhagic shock e. Tension pneumothorax 5. Explain the indications for and the pharmacokinetics of each of the following drugs: a. Lidocaine g. Quinidine b. Bretylium h. Isoproterenol c. Digoxin i. Amiodarone d. Propanolol j. Dopamine e. Verapamil k. Dobutamine f. Pronestyl l. Adenosine (Adenocard®) 6. Summarize the indications and the appropriate techniques for cardioversion and defibrillation. Vanderbilt University Medical Center Emergency General Surgery Service Surgical Residency Rotation and Curriculum 7. Outline the signs and symptoms of acute airway obstruction and define the appropriate intervention in adult and pediatric patients. -

Hypertension: Putting the Pressure on the Silent Killer

HYPERTENSION: PUTTING THE PRESSURE ON THE SILENT KILLER MAY 2016 TABLEHypertension: putting OF the CONTENTS pressure on the silent killer Table of contents UNDERSTANDING HYPERTENSION AND THE LINK TO CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE 2 Understanding hypertension and the link to cardiovascular disease THEThe social SOCIAL and economic AND impact ECONOMIC of hypertension IMPACT OF HYPERTENSION 3 Diagnosing and treating hypertension – what is out there? DIAGNOSINGChallenges to tackling hypertension AND TREATING HYPERTENSION – WHAT IS OUT THERE? 6 Opportunities and focus areas for policymakers CHALLENGES TO TACKLING HYPERTENSION 9 OPPORTUNITIES AND FOCUS AREAS FOR POLICYMAKERS 15 HYPERTENSION: PUTTING THE PRESSURE ON THE SILENT KILLER UNDERSTANDING HYPERTENSION AND THE LINK TO CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE Cardiovascular disease (CVD), or heart disease, is the number one cause of death in the world. 80% of deaths due to CVD occur in countries and poor communities where health systems are weak, and CVD accounts for nearly half of the estimated US$500 billion annual lost economic output associated with noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) in low-income and middle-income countries. In 2012, CVD killed 17.5 million people – the equivalent of every 3 in 10 deaths.1 Of these 17 million deaths a year, over half – 9.4 million - are caused by complications in hypertension, also commonly referred to as raised or high blood pressure2. Hypertension is a risk factor for coronary heart disease and the single most important risk factor for stroke - it is responsible for at least 45% of deaths due to heart disease, and at least 51% of deaths due to stroke. High blood pressure is defined as a systolic blood pressure at or above 140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure at or above 90 mmHg. -

Effects of Immediate Versus Delayed Antihypertensive Therapy on Outcome in the Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Jan A

Original article 847 Effects of immediate versus delayed antihypertensive therapy on outcome in the Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Jan A. Staessena, Lutgarde Thijsa, Robert Fagarda, Hilde Celisa, Willem H. Birkenha¨gerb, Christopher J. Bulpittc, Peter W. de Leeuwd, Astrid E. Fletchere, Franc¸oise Forettef, Gastone Leonettig, Patricia McCormackh, Choudomir Nachevi, Eoin O’Brienh, Jose´ L. Rodicioj, Joseph Rosenfeldk, Cinzia Sartil, Jaakko Tuomilehtol, John Websterm, Yair Yodfatn and Alberto Zanchettig, for the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators Background To assess the impact of immediate versus systolic hypertension. Immediate compared with delayed delayed antihypertensive treatment on the outcome of treatment prevented 17 strokes or 25 major cardiovascular older patients with isolated systolic hypertension, we events per 1000 patients followed up for 6 years. These extended the double-blind placebo-controlled Systolic findings underscore the necessity of early treatment of Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) trial by an open-label isolated systolic hypertension. J Hypertens 22:847–857 & follow-up study lasting 4 years. 2004 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Methods The Syst-Eur trial included 4695 randomized Journal of Hypertension 2004, 22:847–857 patients with minimum age of 60 years and an untreated Keywords: calcium-channel blocker, clinical trial, isolated systolic blood pressure of 160–219 mmHg systolic and below hypertension, outcome, myocardial infarction, stroke 95 mmHg diastolic. The double-blind -

Hypertension and Coronary Heart Disease

Journal of Human Hypertension (2002) 16 (Suppl 1), S61–S63 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9240/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/jhh Hypertension and coronary heart disease E Escobar University of Chile, Santiago, Chile The association of hypertension and coronary heart atherosclerosis, damage of arterial territories other than disease is a frequent one. There are several patho- the coronary one, and of the extension and severity of physiologic mechanisms which link both diseases. coronary artery involvement. It is important to empha- Hypertension induces endothelial dysfunction, exacer- sise that complications and mortality of patients suffer- bates the atherosclerotic process and it contributes to ing a myocardial infarction are greater in hypertensive make the atherosclerotic plaque more unstable. Left patients. Treatment should be aimed to achieve optimal ventricular hypertrophy, which is the usual complication values of blood pressure, and all the strategies to treat of hypertension, promotes a decrease of ‘coronary coronary heart disease should be considered on an indi- reserve’ and increases myocardial oxygen demand, vidual basis. both mechanisms contributing to myocardial ischaemia. Journal of Human Hypertension (2002) 16 (Suppl 1), S61– From a clinical point of view hypertensive patients S63. DOI: 10.1038/sj/jhh/1001345 should have a complete evaluation of risk factors for Keywords: hypertension; hypertrophy; coronary heart disease There is a strong and frequent association between arterial hypertension.8 Hypertension is frequently arterial hypertension and coronary heart disease associated to metabolic disorders, such as insulin (CHD). In the PROCAM study, in men between 40 resistance with hyperinsulinaemia and dyslipidae- and 66 years of age, the prevalence of hypertension mia, which are additional risk factors of atheroscler- in patients who had a myocardial infarction was osis.9 14/1000 men in a follow-up of 4 years. -

Hypertension, Cholesterol, and Aspirin with Cost Info

Diabetes & Your Health High Blood Pressure & Diabetes Aspirin & Did you know as many as two out of three adults with Heart Health diabetes have high blood pressure? High blood pressure Studies have shown is a serious problem. It can raise your chances of stroke, that taking a low- heart attack, eye problems, and kidney disease. dose aspirin every Many people do not know they have high blood pressure day can lower the because they do not have any symptoms. That is why it risk for heart attack is often called “the silent killer.” and stroke. The only way to know if you have high blood pressure is Aspirin can help to have it checked. If you have diabetes, you should those who are at high have your blood pressure checked every time you see risk of heart attack, the doctor. People with diabetes should try to keep their such as people who blood pressure lower than 130 over 80. have diabetes or high blood pressure. Cholesterol & Diabetes Aspirin can also help Keeping your cholesterol and other blood fats, called lipids, under control can people with diabetes help you prevent diabetes problems. Cholesterol and blood lipids that are too who have already high can lead to heart attack and stroke. Many people with diabetes have had a heart attack or problems with their cholesterol and other lipid levels. a stroke, or who have heart disease. You will not know that your cholesterol and blood lipids are at dangerous levels unless you have a blood test to have them checked. Everyone with diabetes Taking an aspirin a should have cholesterol and other lipid levels checked at least once per year. -

Hypertension and the Prothrombotic State

Journal of Human Hypertension (2000) 14, 687–690 2000 Macmillan Publishers Ltd All rights reserved 0950-9240/00 $15.00 www.nature.com/jhh REVIEW ARTICLE Hypertension and the prothrombotic state GYH Lip Haemostasis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology Unit, University Department of Medicine, City Hospital, Birmingham, UK The basic underlying pathophysiological processes related to conventional risk factors, target organ dam- underlying the major complications of hypertension age, complications and long-term prognosis, as well as (that is, heart attacks and strokes) are thrombogenesis different antihypertensive treatments. Further work is and atherogenesis. Indeed, despite the blood vessels needed to examine the mechanisms leading to this being exposed to high pressures in hypertension, the phenomenon, the potential prognostic and treatment complications of hypertension are paradoxically throm- implications, and the possible value of measuring these botic in nature rather than haemorrhagic. The evidence parameters in routine clinical practice. suggests that hypertension appears to confer a Journal of Human Hypertension (2000) 14, 687–690 prothrombotic or hypercoagulable state, which can be Keywords: hypercoagulable; prothrombotic; coagulation; haemorheology; prognosis Introduction Indeed, patients with hypertension are well-recog- nised to demonstrate abnormalities of each of these Hypertension is well-recognised to be an important 1 components of Virchow’s triad, leading to a contributor to heart attacks and stroke. Further- prothrombotic or hypercoagulable state.4 Further- more, effective antihypertensive therapy reduces more, the processes of thrombogenesis and athero- strokes by 30–40%, and coronary artery disease by 2 genesis are intimately related, and many of the basic approximately 25%. Nevertheless the basic under- concepts thrombogenesis can be applied to athero- lying pathophysiological processes underlying both genesis. -

Major Clinical Considerations for Secondary Hypertension And

& Experim l e ca n i t in a l l C Journal of Clinical and Experimental C f a o r d l i a o Thevenard et al., J Clin Exp Cardiolog 2018, 9:11 n l o r g u y o Cardiology DOI: 10.4172/2155-9880.1000616 J ISSN: 2155-9880 Review Article Open Access Major Clinical Considerations for Secondary Hypertension and Treatment Challenges: Systematic Review Gabriela Thevenard1, Nathalia Bordin Dal-Prá1 and Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho2* 1Santa Casa de Misericordia Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil 2Department of scientific production, Street Ipiranga, São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil *Corresponding author: Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho, Department of scientific production, Street Ipiranga, São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil, Tel: +5517981666537; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: October 30, 2018; Accepted date: November 23, 2018; Published date: November 30, 2018 Copyright: ©2018 Thevenard G, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Introduction: In this context, secondary arterial hypertension (SH) is defined as an increase in systemic arterial pressure (SAP) due to an identifiable cause. Only 5 to 10% of patients suffering from hypertension have a secondary form, while the vast majorities have essential hypertension. Objective: This study aimed to describe, through a systematic review, the main considerations on secondary hypertension, presenting its clinical data and main causes, as well as presenting the types of treatments according to the literary results. -

Pulmonary Hypertension ______

Pulmonary Hypertension _________________________________________ What is it? High blood pressure in the arteries that supply the lungs is called pulmonary hypertension (PH) or pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). The blood pressure measured by a cuff on your arm isn’t directly related to the pressure in your lungs. The blood vessels that supply the lungs constrict and their walls thicken, so they can’t carry as much blood. As in a kinked garden hose, pressure builds up and backs up. The heart works harder, trying to force the blood through. If the pressure is high enough, eventually the heart can’t keep up, and less blood can circulate through the lungs to pick up oxygen. Patients then become tired, dizzy and short of breath. If a pre-existing disease triggered the PH, doctors call it secondary pulmonary hypertension. That’s because it’s secondary to another problem, such as a left heart or lung disorder. However, congenital heart disease can cause PH that’s similar to PH when the cause isn’t known, i.e., idiopathic or unexplained pulmonary arterial hypertension. In this case, the PAH is considered pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease, such as associated with a VSD or ASD (either repaired or unrepaired). The problem is due to scarring in the small arteries in the lung. It’s important to repair congenital heart problems (when possible) before permanent pulmonary hypertensive changes develop. Intracardiac left-to-right shunts (such as a ventricular or atrial septal defect, a hole in the wall between the two ventricles or atria) can cause too much blood flow through the lungs.