American Yoga 169

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yoga and Pilates: What’S the Difference? by Sherri R

Yoga and Pilates: What’s the difference? By Sherri R. Betz, PT, GCS, PMA®-CPT Have you ever wondered… “What are the differences between Yoga and Pilates?” Someone jokingly said, “The difference between Pilates and Yoga is that in Yoga you close your eyes and think about god and in Pilates you keep your eyes open and think about your abs!” One guru said the purpose of Yoga is to become more flexible so that you could sit comfortably to meditate. Yoga certainly is more than that. I write this in trepidation of offending the beautiful Yoga and Pilates practitioners around the world. I hope to distill some of the information about Yoga and Pilates looking at some of the differences and similarities between them to help practitioners understand these popular forms of movement. My yoga practice began in Louisiana (when no one did yoga there!) at about the age of 15. At the local library, I happened to pick up The Sivananda Companion to Yoga and started trying out some of the poses and breathing. Actually, I skipped the breathing and avoided it for many years until I did my Pilates training and was forced to learn to breathe! Now I am devoted to my Ashtanga/Vinyasa Yoga practice and my Pilates work to keep my body in shape and to add a spiritual component to my life. It has been very interesting to compare a movement practice that has been around for 2000 years with one that has been around for only about 80 years. Yoga: Navasana (Boat Pose) Pilates: Teaser Common Forms of Yoga Practice in the United States: Yoga was brought to us by Hindus practicing in India. -

I on an Empty Stomach After Evacuating the Bladder and Bowels

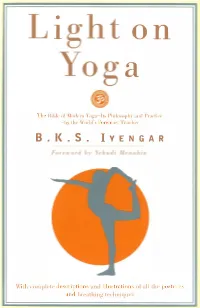

• I on a Tllt' Bi11lr· ol' \lodt•nJ Yoga-It� Philo�opl1� and Prad il't' -hv thr: World" s Fon-·mo �l 'l'r·ar·lwr B • I< . S . IYENGAR \\ it h compldc· dt·!wription� and illustrations of all tlw po �tun·� and bn·athing techniqn··� With More than 600 Photographs Positioned Next to the Exercises "For the serious student of Hatha Yoga, this is as comprehensive a handbook as money can buy." -ATLANTA JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION "The publishers calls this 'the fullest, most practical, and most profusely illustrated book on Yoga ... in English'; it is just that." -CHOICE "This is the best book on Yoga. The introduction to Yoga philosophy alone is worth the price of the book. Anyone wishing to know the techniques of Yoga from a master should study this book." -AST RAL PROJECTION "600 pictures and an incredible amount of detailed descriptive text as well as philosophy .... Fully revised and photographs illustrating the exercises appear right next to the descriptions (in the earlier edition the photographs were appended). We highly recommend this book." -WELLNESS LIGHT ON YOGA § 50 Years of Publishing 1945-1995 Yoga Dipika B. K. S. IYENGAR Foreword by Yehudi Menuhin REVISED EDITION Schocken Books New 1:'0rk First published by Schocken Books 1966 Revised edition published by Schocken Books 1977 Paperback revised edition published by Schocken Books 1979 Copyright© 1966, 1968, 1976 by George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

—The History of Hatha Yoga in America: The

“The History of Hatha Yoga in America: the Americanization of Yoga” Book proposal By Ira Israel Although many American yoga teachers invoke the putative legitimacy of the legacy of yoga as a 5000 year old Indian practice, the core of the yoga in America – the “asanas,” or positions – is only around 600 years old. And yoga as a codified 90 minute ritual or sequence is at most only 120 years old. During the period of the Vedas 5000 years ago, yoga consisted of groups of men chanting to the gods around a fire. Thousands of years later during the period of the Upanishads, that ritual of generating heat (“tapas”) became internalized through concentrated breathing and contrary or bipolar positions e.g., reaching the torso upwards while grounding the lower body downwards. The History of Yoga in America is relatively brief yet very complex and in fact, I will argue that what has happened to yoga in America is tantamount to comparing Starbucks to French café life: I call it “The Americanization of Yoga.” For centuries America, the melting pot, has usurped sundry traditions from various cultures; however, there is something unique about the rise of the influence of yoga and Eastern philosophy in America that make it worth analyzing. There are a few main schools of hatha yoga that have evolved in America: Sivananda, Iyengar, Astanga, and later Bikram, Power, and Anusara (the Kundalini lineage will not be addressed in this book because so much has been written about it already). After practicing many of these different “styles” or schools of hatha yoga in New York, North Carolina, Florida, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and Paris as well as in Thailand and Indonesia, I became so fascinated by the history and evolution of yoga that I went to the University of California at Santa Barbara to get a Master of Arts Degree in Hinduism and Buddhism which I completed in 1999. -

Yoga Practices As Identity Capital

MÅNS BROO Yoga practices as identity capital Preliminary notes from Turku, Finland s elsewhere in Finland, different types of yoga practices are popular in the Acity of Åbo/Turku. But how do practitioners view their own relationship to their practice, and further, what do they feel that they as individuals gain from it? Through in-depth interviews with yoga teachers in the city of Turku and using the theoretical framework of social psychologists James E. Côte’s and Charles G. Levine’s (2002) concept of identity capital, I wish to examine ways in which individuals, in what could be called a post-secular society, construct a meaningful sense of self and of individual agency. The observations offered in this article represent preliminary notes for a larger work on yoga in Turku, conducted at the ‘Post-Secular Culture and a Changing Religious Landscape’ research project at Åbo Akademi University, devoted to qualitative and eth- nographic investigations of the changing religious landscape in Finland. But before I go on to my theory and material, let me just briefly state some- thing about yoga in Finland in general and in the town of Turku in particular. Turku may not be the political capital of Finland any longer, but is by far the oldest city in the country, with roots going back to the thirteenth century. However, as a site of yoga practice, Turku has a far shorter history than this. As in many other Western countries, the first people in Finland who talked about yoga as a beneficial practice Westerners might take up rather than just laugh at as some weird oriental custom were the theosophists. -

Prop Technology Upcoming Workshops

Upcoming Workshops – continued from cover Summer 2012 Mary Obendorfer and Eddy Marks Janet MacLeod Patricia Walden 5-Day Intermediate Intensive October 19 – 21, 2012 February 1 – 3, 2013 June 19 – 23, 2013 Boise Yoga Center, Boise, ID Tree House Iyengar Yoga, Seattle, WA Yoga Northwest, Bellingham, WA www.boiseyogacenter.com www.thiyoga.com www.yoganorthwest.com 208.343.9786 206.361.9642 360.647.0712 *member discount available* Carolyn Belko Joan White October 19 – 21, 2012 Yoga and Scoliosis with Rita Lewis-Manos October 18 – 20, 2013 Mind Your Body, Pocatello, ID March 15 – 17, 2013 Tree House Iyengar Yoga, Seattle, WA www.mybpocatello.com/home Rose Yoga of Ashland, Ashland, OR www.thiyoga.com Prop Technology 208.234.220 roseyogacenter.com 206.361.9642 2012 IYANW Officers: by Tonya Garreaud 541.292.3408 *member discount available* Anne Geil - President Chris Saudek Marcia Gossard - Vice President It might come as a surprise to people who know me that the first thing I reach for each morning is my November 16 – 18, 2012 Carrie Owerko Karin Brown - Treasurer & Grants smart phone. After all, I was a late adopter—I still don’t hand out my cell number very often—I prefer Julie Lawrence Yoga Center, Portland, OR June 14 – 16, 2013 Angela McKinlay - Secretary not to be bothered. In general, I’m not a fan of cell phones. It is extremely difficult for me to maintain www.jlyc.com Julie Lawrence Yoga Center, Portland, OR Tonya Garreaud - Membership Chair equanimity when I see poor driving caused by the distracting use of a cell phone. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

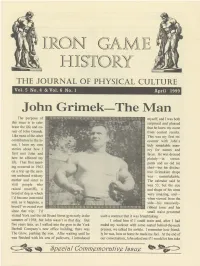

HOW STEVE REEVES TRAINED by John Grimek

IRON GAME HISTORY VOL.5No.4&VOL. 6 No. 1 IRON GAME HISTORY ATRON SUBSCRIBERS THE JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL CULTURE P Gordon Anderson Jack Lano VOL. 5 NO. 4 & VOL. 6 NO. 1 Joe Assirati James Lorimer SPECIAL DOUBL E I SSUE John Balik Walt Marcyan Vic Boff Dr. Spencer Maxcy TABLE OF CONTENTS Bill Brewer Don McEachren Bill Clark David Mills 1. John Grimek—The Man . Terry Todd Robert Conciatori Piedmont Design 6. lmmortalizing Grimek. .David Chapman Bruce Conner Terry Robinson 10. My Friend: John C. Grimek. Vic Boff Bob Delmontique Ulf Salvin 12. Our Memories . Pudgy & Les Stockton 4. I Meet The Champ . Siegmund Klein Michael Dennis Jim Sanders 17. The King is Dead . .Alton Eliason Mike D’Angelo Frederick Schutz 19. Life With John. Angela Grimek Lucio Doncel Harry Schwartz 21. Remembering Grimek . .Clarence Bass Dave Draper In Memory of Chuck 26. Ironclad. .Joe Roark 32. l Thought He Was lmmortal. Jim Murray Eifel Antiques Sipes 33. My Thoughts and Reflections. .Ken Rosa Salvatore Franchino Ed Stevens 36. My Visit to Desbonnet . .John Grimek Candy Gaudiani Pudgy & Les Stockton 38. Best of Them All . .Terry Robinson 39. The First Great Bodybuilder . Jim Lorimer Rob Gilbert Frank Stranahan 40. Tribute to a Titan . .Tom Minichiello Fairfax Hackley Al Thomas 42. Grapevine . Staff James Hammill Ted Thompson 48. How Steve Reeves Trained . .John Grimek 50. John Grimek: Master of the Dance. Al Thomas Odd E. Haugen Joe Weider 64. “The Man’s Just Too Strong for Words”. John Fair Norman Komich Harold Zinkin Zabo Koszewski Co-Editors . , . Jan & Terry Todd FELLOWSHIP SUBSCRIBERS Business Manager . -

An Excursus on the Subtle Body in Tantric Buddhism. Notes

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A. K. Narain University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA EDITORS L. M.Joshi Ernst Steinkellner Punjabi University University of Vienna Patiala, India Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universite de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, fapan Bardwell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfield, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Roger Jackson FJRN->' Volume 6 1983 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES A reconstruction of the Madhyamakdvatdra's Analysis of the Person, by Peter G. Fenner. 7 Cittaprakrti and Ayonisomanaskdra in the Ratnagolravi- bhdga: Precedent for the Hsin-Nien Distinction of The Awakening of Faith, by William Grosnick 35 An Excursus on the Subtle Body in Tantric Buddhism (Notes Contextualizing the Kalacakra)1, by Geshe Lhundup Sopa 48 Socio-Cultural Aspects of Theravada Buddhism in Ne pal, by Ramesh Chandra Tewari 67 The Yuktisas(ikakdrikd of Nagarjuna, by Fernando Tola and Carmen Dragonetti 94 The "Suicide" Problem in the Pali Canon, by Martin G. Wiltshire \ 24 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. Buddhist and Western Philosophy, edited by Nathan Katz 141 2. A Meditators Diary, by Jane Hamilton-Merritt 144 3. The Roof Tile ofTempyo, by Yasushi Inoue 146 4. Les royaumes de I'Himalaya, histoire et civilisation: le La- dakh, le Bhoutan, le Sikkirn, le Nepal, under the direc tion of Alexander W. Macdonald 147 5. Wings of the White Crane: Poems of Tskangs dbyangs rgya mtsho (1683-1706), translated by G.W. Houston The Rain of Wisdom, translated by the Nalanda Transla tion Committee under the Direction of Chogyam Trungpa Songs of Spiritual Change, by the Seventh Dalai Lama, Gyalwa Kalzang Gyatso 149 III. -

Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2015 Bodies Bending Boundaries: Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks Kimberley J. Pingatore As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Pingatore, Kimberley J., "Bodies Bending Boundaries: Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks" (2015). MSU Graduate Theses. 3010. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3010 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BODIES BENDING BOUNDARIES: RELIGIOUS, SPIRITUAL, AND SECULAR IDENTITIES OF MODERN POSTURAL YOGA IN THE OZARKS A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, Religious Studies By Kimberley J. Pingatore December 2015 Copyright 2015 by Kimberley Jaqueline Pingatore ii BODIES BENDING BOUNDARIES: RELIGIOUS, SPIRITUAL, AND SECULAR IDENTITIES OF MODERN POSTURAL YOGA IN THE OZARKS Religious Studies Missouri State University, December 2015 Master of Arts Kimberley J. -

Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS

Breath of Life Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS Prana Vayu: 4 The Breath of Vitality Apana Vayu: 9 The Anchoring Breath Samana Vayu: 14 The Breath of Balance Udana Vayu: 19 The Breath of Ascent Vyana Vayu: 24 The Breath of Integration By Sandra Anderson Yoga International senior editor Sandra Anderson is co-author of Yoga: Mastering the Basics and has taught yoga and meditation for over 25 years. Photography: Kathryn LeSoine, Model: Sandra Anderson; Wardrobe: Top by Zobha; Pant by Prana © 2011 Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the U.S.A. All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of editorial or pictorial content in any manner without written permission is prohibited. Introduction t its heart, hatha yoga is more than just flexibility or strength in postures; it is the management of prana, the vital life force that animates all levels of being. Prana enables the body to move and the mind to think. It is the intelligence that coordinates our senses, and the perceptible manifestation of our higher selves. By becoming more attentive to prana—and enhancing and directing its flow through the Apractices of hatha yoga—we can invigorate the body and mind, develop an expanded inner awareness, and open the door to higher states of consciousness. The yoga tradition describes five movements or functions of prana known as the vayus (literally “winds”)—prana vayu (not to be confused with the undivided master prana), apana vayu, samana vayu, udana vayu, and vyana vayu. These five vayus govern different areas of the body and different physical and subtle activities. -

{PDF} a History of Modern Yoga: Patanjali and Western Esotericism

A HISTORY OF MODERN YOGA: PATANJALI AND WESTERN ESOTERICISM Author: Elizabeth de Michelis Number of Pages: 302 pages Published Date: 12 Nov 2005 Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9780826487728 DOWNLOAD: A HISTORY OF MODERN YOGA: PATANJALI AND WESTERN ESOTERICISM A History of Modern Yoga: Patanjali and Western Esotericism PDF Book NET, we will deal with storing and retrieving unstructured data with Blobs, then will move to Tables to insert and update entities in a structured NoSQL fashion. The authors engage in practical applications of ideas and approaches, and present a rigorous and informed view of the subject, that is at the same time professionally and practically focused. It also includes: Wiimote Remote Control car: Steer your Wiimote-controlled car by tilting the controller left and right; Wiimote white board: Create a multi-touch interactive white board; and, Holiday Lights: Synchronize your holiday light display with music to create your own light show. Silver was formed through the supernovas of stars, and its history continues to be marked by cataclysm. Choose from filling and tasty pasta rice meals, super fast pancakes frittatas, dips, dressings, pour over sauces more. Picture Yourself Networking Your Home or Small OfficeThis is the definitive guide for Symbian C developers looking to use Symbian SQL in applications or system software. 1 reason for workplace absence in the UK. An Ivey CaseMate has also been created for this book at https:www. As such, it fills a major gap in the study of how people learn and reason in the context of particular subject matter domains and how instruction can be improved in order to facilitate better learning and reasoning. -

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Dhyana Vahini 5 Publisher’s Note 6 PREFACE 7 Chapter I. The Power of Meditation 10 Binding actions and liberating actions 10 Taming the mind and the intelligence 11 One-pointedness and concentration 11 The value of chanting the divine name and meditation 12 The method of meditation 12 Chapter II. Chanting God’s Name and Meditation 14 Gauge meditation by its inner impact 14 The three paths of meditation 15 The need for bodily and mental training 15 Everyone has the right to spiritual success 16 Chapter III. The Goal of Meditation 18 Control the temper of the mind 18 Concentration and one-pointedness are the keys 18 Yearn for the right thing! 18 Reaching the goal through meditation 19 Gain inward vision 20 Chapter IV. Promote the Welfare of All Beings 21 Eschew the tenfold “sins” 21 Be unaffected by illusion 21 First, good qualities; later, the absence of qualities 21 The placid, calm, unruffled character wins out 22 Meditation is the basis of spiritual experience 23 Chapter V. Cultivate the Blissful Atmic Experience 24 The primary qualifications 24 Lead a dharmic life 24 The eight gates 25 Wish versus will 25 Take it step by step 25 No past or future 26 Clean and feed the mind 26 Chapter VI. Meditation Reveals the Eternal and the Non-Eternal 27 The Lord’s grace is needed to cross the sea 27 Why worry over short-lived attachments? 27 We are actors in the Lord’s play 29 Chapter VII.