Transgender in India: a Semiotic and Reception Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

Khamoshiyan Now on Home Video by : INVC Team Published on : 9 Apr, 2015 12:00 AM IST

Khamoshiyan now on Home Video By : INVC Team Published On : 9 Apr, 2015 12:00 AM IST INVC NEWS Mumbai, Horror, drama, melodies, beauty, “Khamoshiyan” has it all. Recently released, the movie features Sapna Pabbi, Gurmeet Chaudhary and Ali Fazal. Shemaroo Entertainment now releases “Khamoshiyan” on Home Video. The film is directed by Karan Darra and produced by Mahesh Bhatt and Mukesh Bhatt in association with Vishesh Films. A young novelist KABIR (Ali Fazal) is a one-book wonder. He is on an inspirational journey to find himself and to write his book. He meets a young and beautiful lady MEERA (Sapna Pabbi) who runs the isolated guest-house which he finds eerie. Meera is married to the owner of this guest-house JAIDEV (Gurmeet Choudhary) who was once a rich paper mill owner, he had disguised himself as a charming man but is a controlling demon within. Kabir begins to encounter unusual things and discover secrets about the house and Meera. But Meera is evasive about these suspicious incidents that are taking place, which if Kabir finds out, would threaten to destroy her. The more Kabir interacts with Meera about these strange incidents the more he gets drawn towards her. What are the secrets that are hidden in her silences? Khamoshiyan is a horror movie with melodious music tracks and serves as perfect bollywood weekend dose!! URL : https://www.internationalnewsandviews.com/khamoshiyan-now-on-home-video/ 12th year of news and views excellency Committed to truth and impartiality Copyright © 2009 - 2019 International News and Views Corporation. All rights reserved. -

Persons – 2012

Persons – 2012 • Omita Paul appointed as the Secretary of the President: Appointment Committee of the Cabinet(ACC) appointed Omita Paul as the Secretary of the President on 24 July 2012. Her tenure as Secretary to the President is for contract basis. Omita is 63 years old. She replaced Christy L Fernandez. Omita Paul was appointed as the information commissioner in the central Information Commission in the year 2009 for the short duration of time at the end of the UPA-I government’s tenure. In addition, she had resigned to join as the Advisor in Finance Ministry from 2004 to 2009. Omita is a retired officer from Indian Information Service (IIS) from 1973 batch. Omita Paul is the wife of KK Paul. KK Paul was the former Delhi Police Commissioner. He is working as the member of the Union Public Service Commission. • Hesham Kandil Named Egypt's New Prime Minister: Egypt’s President Mohamed Morsi elected fifty-year- old Hisham Kandil as the country’s Prime Minister on 26 July. Morsi ordered the country’s former minister of water resources and irrigation, Kandil to form a new government. Kandil, holds an engineering degree from Cairo University in the year 1984 and a Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina in the year 1993. Kandil will be the first Egyptian prime minister to wear a beard, which is a sure sign of change in the country. A number of more experienced names were suggested for the prestigious role, but Morsi chose Kandil, a relatively lesser-known face as the Prime Minister of the country, this could be because he wanted someone unlikely to threaten or overshadow him. -

Dated : 23/4/2016

Dated : 23/4/2016 Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name Defaulting Year 01750017 DUA INDRAPAL MEHERDEEP U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750020 ARAVIND MYLSWAMY U01120TZ2008PTC014531 M J A AGRO FARMS PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750025 GOYAL HEMA U18263DL1989PLC037514 LEISURE WEAR EXPORTS 2007-08 LTD. 01750030 MYLSWAMY VIGNESH U01120TZ2008PTC014532 M J V AGRO FARM PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750033 HARAGADDE KUMAR U74910KA2007PTC043849 HAVEY PLACEMENT AND IT 2008-09, 2009-10 SHARATH VENKATESH SOLUTIONS (INDIA) PRIVATE 01750063 BHUPINDER DUA KAUR U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750107 GOYAL VEENA U18263DL1989PLC037514 LEISURE WEAR EXPORTS 2007-08 LTD. 01750125 ANEES SAAD U55101KA2004PTC034189 RAHMANIA HOTELS 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750125 ANEES SAAD U15400KA2007PTC044380 FRESCO FOODS PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750188 DUA INDRAPAL SINGH U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750202 KUMAR SHILENDRA U45400UP2007PTC034093 ASHOK THEKEDAR PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750208 BANKTESHWAR SINGH U14101MP2004PTC016348 PASHUPATI MARBLES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750212 BIAPPU MADHU SREEVANI U74900TG2008PTC060703 SCALAR ENTERPRISES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750259 GANGAVARAM REDDY U45209TG2007PTC055883 S.K.R. INFRASTRUCTURE 2008-09, 2009-10 SUNEETHA AND PROJECTS PRIVATE 01750272 MUTHYALA RAMANA U51900TG2007PTC055758 NAGRAMAK IMPORTS AND 2008-09, 2009-10 EXPORTS PRIVATE LIMITED 01750286 DUA GAGAN NARAYAN U74120DL2007PTC169008 -

Kasoor Movie Download in Hindi Dubbed Mp4

Kasoor Movie Download In Hindi Dubbed Mp4 1 / 4 Kasoor Movie Download In Hindi Dubbed Mp4 2 / 4 3 / 4 Distributed by, Vishesh Films. Release date. 2 April 2004 (2004-04-02). Running time. 130 minutes. Country, India. Language, Hindi. Budget, 5 crore. Box office, 80.49 crore. Murder is a 2004 Indian Hindi erotic thriller film directed by Anurag Basu and produced by . Viraj Adhav as the Hindi dubbing voice); Mallika Sherawat as Simran Sehgal.. 14 Aug 2018 - 53 secCheck out the teaser of Jr NTR and Trivikram Srinivas' upcoming film 'Aravinda Sametha .. Hollywood Movies Hindi Dubbed Free Download 3gp,Mp4 Mobile Movies . Collection () 82 GB Free Download Dil Ka Kya Kasoor () Hindi Movie HD MB Free.. Free Download Mp4 3Gp AVI Mobile Movies, Mp4 HD Movies 340p 480p 720p, Hollywood Hindi Dubbed Movies, South Indian Hindi Dubbed Movies, Marathi.. Motu Patlu - Joker Motu Patlu - Download mp4 3gp Videos. Laung Laachi Title Song Mannat Noor - Download mp4 3gp Videos. Motu Patlu In Hindi Cartoon.. Download Dil ka kya kasoor movie type Mp3 3gp mp4 and watch Dil ka kya kasoor . Dil Ka Kya Kasoor (1992) Full Length Hindi Movie - Prithvi, Divya Bharti, . Divya Bharti Purpose Prithvi Best Scenes Movie Dil Ka Kiya Kasoor 1992 Hd.. 5 Aug 2018 . Super Khiladi 4 2018 Hindi Dubbed Movie Download HDRip 720p Dual Audio IMDb . Wapking and DJmaza official mp4, 3gp, avi videos.. 25 Jul 2018 . 2012 Movies Online Watch Free Download HD Mp4 Mobile Movies. (2012) Hindi Dubbed Full Movie, LOL (2012) Hindi Dubbed Full Movie.. kasoor full movie Video Download Full HD, 3gp, Mp4, HD Mp4-HDVdz.com. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN NO 26. MG ROAD AND ABERDEEN BAZAR , NICOBAR PORT BLAIR -744101 704412829 704412829 ISLAND ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR ,A & N ISLANDS PORT BLAIR IBKL0001498 8 7044128298 8 744259002 UPPER GROUND FLOOR, #6-5-83/1, ANIL ANIL NEW BUS STAND KUMAR KUMAR ANDHRA ROAD, BHUKTAPUR, 897889900 ANIL KUMAR 897889900 PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD ADILABAD 504001 ADILABAD IBKL0001090 1 8978899001 1 1ST FLOOR, 14- 309,SREERAM ENCLAVE,RAILWAY FEDDER ROADANANTAPURA ANDHRA NANTAPURANDHRA ANANTAPU 08554- PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTAPUR PRADESH R IBKL0000208 270244 D.NO.16-376,MARKET STREET,OPPOSITE CHURCH,DHARMAVA RAM- 091 ANDHRA 515671,ANANTAPUR DHARMAVA 949497979 PRADESH ANANTAPUR DHARMAVARAM DISTRICT RAM IBKL0001795 7 515259202 SRINIVASA SRINIVASA IDBI BANK LTD, 10- RAO RAO 43, BESIDE SURESH MYLAPALL SRINIVASA MYLAPALL MEDICALS, RAILWAY I - RAO I - ANDHRA STATION ROAD, +91967670 MYLAPALLI - +91967670 PRADESH ANANTAPUR GUNTAKAL GUNTAKAL - 515801 GUNTAKAL IBKL0001091 6655 +919676706655 6655 18-1-138, M.F.ROAD, AJACENT TO ING VYSYA BANK, HINDUPUR , ANANTAPUR DIST - 994973715 ANDHRA PIN:515 201 9/98497191 PRADESH ANANTAPUR HINDUPUR ANDHRA PRADESH HINDUPUR IBKL0001162 17 515259102 AGRICULTURE MARKET COMMITTEE, ANANTAPUR ROAD, TADIPATRI, 085582264 ANANTAPUR DIST 40 ANDHRA PIN : 515411 /903226789 PRADESH ANANTAPUR TADIPATRI ANDHRA PRADESH TADPATRI IBKL0001163 2 515259402 BUKARAYASUNDARA M MANDAL,NEAR HP GAS FILLING 91 ANDHRA STATION,ANANTHAP ANANTAPU 929710487 PRADESH ANANTAPUR VADIYAMPETA UR -

Strengthening Bonds Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’S Visit to Bangladesh Potpourri

STROKES OF HERITAGE Odisha’s indigenous art of pattachitra Volume 35 | Issue 02 | 2021 TRAVELLING WITH THE BUDDHA Buddhist linkages across Southeast Asia STRENGTHENING BONDS Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Bangladesh POTPOURRI Potpourri Events of the season MAY, 2021 ID-UL- FITR One of the most important festivals in the Muslim calendar, Id-ul- 14 Fitr, also called Eid al-Fitr, marks the end of Ramadan, the Muslim holy month of fasting. The day is celebrated by offering prayers, exchanging gifts and wishes, and donning new clothes. A special sweet dish called sivayyan (roasted vermicelli cooked in milk and garnished with dry fruits) is prepared on this occasion. WHERE: Across the country 14-16 MAY, 2021 26 MAY, 2021 BUDDHA PURNIMA Celebrated on the full moon day of the Hindu month of Vaisakh (April/May), Buddha Purnima, also known as Buddha Jayanti and Vesak, marks the birth of Lord Gautama Buddha or the Enlightened One. Devotees visit temples, light candles and incense sticks, and offer prayers and sweets. Devotees also dress in white on this day. WHERE: Across the country DHUNGRI MELA Held in the premises of the revered Hadimba Temple in Himachal Pradesh’s picturesque town of Manali, the annual Dhungri Mela is celebrated to honour the birth of Goddess Hadimba. The three-day mela or fair features several stalls offering local delicacies and handcrafted products. The main attraction is the arrival of local deities, decked in ornate jewellery, from the surrounding villages in decorated palanquins. WHERE: Manali, Himachal Pradesh INDIA PERSPECTIVES | 2 | 21 JUNE, 2021 21 JUNE, 2021 INTERNATIONAL DAY OF YOGA HEMIS TSECHU Observed annually by people across the country, Touted to be one of the most vibrant festivals of Leh, the and the globe, the International Day of Yoga (IDY) annual Hemis Tsechu or Hemis Festival marks the birth of is a celebration of the ancient Indian practice of Guru Padmasambhava, the Indian Buddhist mystic. -

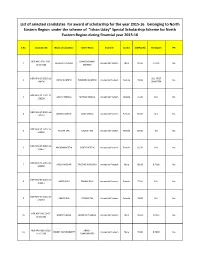

Ishan Uday-NER-2015-16-Revised

List of selected candidates for award of scholarship for the year 2015-16 belonging to North Eastern Region under the scheme of "Ishan Uday" Special Scholarship Scheme for North Eastern Region during financial year 2015-16 S.No. Candidate ID Name of Candidate Father Name Domicile Gender SSE(Pass%) UG Degree PH NER-ARU-GEN-2015- MANOJ KUMAR 1 ABHISHEK KUMAR Arunachal Pradesh Male 90.60 B.Tech No 16-124026 SHARMA NER-ARU-ST-2015-16- BSc. FIRST 2 ADAM GAMKAK TUMBOM GAMKAK Arunachal Pradesh Female 78.60 No 148136 SEMESTER NER-ARU-ST-2015-16- 3 AGAYU MENDA MURALI MENDA Arunachal Pradesh Female 75.20 B.A. No 158238 NER-ARU-ST-2015-16- 4 AMBEYA LINGGI VIJAY LINGGI Arunachal Pradesh Female 85.00 B.A No 137052 NER-ARU-ST-2015-16- 5 AMUM TAKI KALING TAKI Arunachal Pradesh Female 83.08 BA No 142204 NER-ARU-ST-2015-16- 6 ANGKINA PERTIN BORTO PERTIN Arunachal Pradesh Female 83.20 B.A. No 169657 NER-ARU-ST-2015-16- 7 ANIL NANGKAR TAGONG NANGKAR Arunachal Pradesh Male 88.40 B. Tech No 106659 NER-ARU-ST-2015-16- 8 ANITA BAKI TANAM BAKI Arunachal Pradesh Female 77.00 B.A. No 161211 NER-ARU-ST-2015-16- 9 ANJUTI PUL ATEOSO PUL Arunachal Pradesh Female 76.60 B.A No 131063 NER-MIZ-OBC-2015- 10 ARBIN THAKUR BIRINDER THAKUR Arunachal Pradesh Male 76.00 B.tech No 16-135202 NER-ARU-GEN-2015- ABHIJIT 11 ARIJEET CHAKRABORTY Arunachal Pradesh Male 76.80 B.TECH No 16-131368 CHAKRABORTY NER-ARU-OBC-2015- 12 ARUNA BHARATI SUGRIV PRASAD Arunachal Pradesh Female 83.60 B.TECH No 16-123737 NER-ARU-ST-2015-16- 13 ASENG MESSAR TABIT MESSAR Arunachal Pradesh Female 81.00 BA No 123216 NER-ARU-ST-2015-16- 14 ATOSHA BELLAI LAKHRESHA BELLAI Arunachal Pradesh Male 88.40 B.A. -

Film and Music Rajnikant

FILM AND MUSIC RAJNIKANT ajnikanth (Born Shivaji Rao D.O.B. : 12th Dec., 1950 th Gaikwad) was born on 12 Place of Birth : Karnataka December, 1950. He is an R Married to : Latha Rajnikant I n d i a n f i l m a c t o r, m e d i a Awarded : Padma Bhushan personality. He has acted in Vijay Award Hollywood, Bollywood, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam and Bengali Films as well. He started acting caeer while employed with Bangalore Transport Service as a bus conductor. He associated with Madras Film Institute in 1973 to pursue diploma in acting. He began his cinematic career through the Tamil film (Apoorna Raagangal). The film won three National film awards. After the success of this film his career has grown many fold. He is a famous celebrity in the film industry. Till now, he had won 42 awards. Also he has been awarded with Padma Bhushan Vijay Award, Raj Kapoor Award, NDTV award and many more. FILM AND MUSIC AMITABH BACHCHAN mitabh Bachchan was born D.O.B. : 11th Oct., 1942 on 11th October, 1942, in Place of Birth : Allahabad, India AAllahabad, Uttar Pradesh. Married to : Jaya Bachchan His father Harivansh Rai Bachchan Awards : Padma Vibhushan, was a famous Hindi poet. Amitabh Film Fare and means 'Light that will never die'. many more Amitabh did his schooling from Sherwood College, Nainital and graduation from Kirorimal College, Delhi University. Amitabh Bachchan is married to actress Jaya Bhachchan. The couple have two children, Shweta Nanda and Abhishek Bachchan. As an actor his first film was Saat Hindustani directed by Khwaja. -

Beneath the Red Dupatta: an Exploration of the Mythopoeic Functions of the 'Muslim' Courtesan (Tawaif) in Hindustani Cinema

DOCTORAL DISSERTATIO Beneath the Red Dupatta: an Exploration of the Mythopoeic Functions of the ‘Muslim’ Courtesan (tawaif) in Hindustani cinema Farhad Khoyratty Supervised by Dr. Felicity Hand Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Germanística Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements iv 1. Introduction 1 2. Methodology & Literature Review 5 2.1 Methodology 5 2.2 Towards Defining Hindustani Cinema and Bollywood 9 2.3 Gender 23 2.3.1 Feminism: the Three Waves 23 2.4 Feminist Film Theory and Laura Mulvey 30 2.5 Queer Theory and Judith Butler 41 2.6 Discursive Models for the Tawaif 46 2.7 Conclusion 55 3. The Becoming of the Tawaif 59 3.1 The Argument 59 3.2 The Red Dupatta 59 3.3 The Historical Tawaif – the Past’s Present and the Present’s Past 72 3.4 Geisha and Tawaif 91 4. The Courtesan in the Popular Hindustani cinema: Mapping the Ethico-Ideological and Mythopoeic Space She Occupies 103 4.1 The Argument 103 4.2 Mythopoeic Functions of the Tawaif 103 4.3 The ‘Muslim’ Courtesan 120 4.4 Agency of the Tawaif 133 ii 4.5 Conclusion 147 5. Hindustani cinema Herself: the Protean Body of Hindustani cinema 151 5.1 The Argument 151 5.2 Binary Narratives 151 5.3 The Politics of Kissing in Hindustani Cinema 187 5.4 Hindustani Cinema, the Tawaif Who Seeks Respectability 197 Conclusion 209 Bibliography 223 Filmography 249 Webography 257 Photography 261 iii Dedicated to My Late Father Sulliman For his unwavering faith in all my endeavours It is customary to thank one’s supervisor and sadly this has become such an automatic tradition that I am lost for words fit enough to thank Dr. -

Downloads/NZJAS-%20Dec07/02Booth6.Pdfarameters.Html

Ph.D. Thesis ( FEMALE PROTAGONIST IN HINDI CINEMA: Women’s Studies A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF REPRESENTATIVE FILMS FROM 1950 TO 2000 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ) Doctor of Philosophy IN WOMEN’S STUDIES SIFWAT MOINI BY SIFWAT MOINI UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. PITABAS PRADHAN (Associate Professor) 201 6 ADVANCED CENTRE FOR WOMEN’S STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 (INDIA) 2016 DEPARTMENT OF MASS COMMUNICATION ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY Dr. Pitabas Pradhan Associate Professor Certificate This is to certify that Ms. Sifwat Moini has completed her Ph.D. thesis entitled ‘Female Protagonist in Hindi Cinema: A Comparative Study of Representative Films from 1950 to 2000’ under my supervision. This thesis has been submitted to the Advanced Centre for Women’s Studies, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy. It is further certified that this thesis represents original work and to the best of my knowledge has not been submitted for any degree of this university or any other university. (Dr. Pitabas Pradhan) Supervisor Sarfaraz House, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh-202002 Phone: 0571-2704857, Ext.: 1355,Email: [email protected], [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I owe all of my thankfulness to the existence of the Almighty and the entities in which His munificence is reflected for the completion of this work. My heartfelt thankfulness is for my supervisor, Dr. Pitabas Pradhan. His presence is a reason of encouragement, inspiration, learning and discipline. His continuous support, invaluable feedback and positive criticism made me sail through. I sincerely thank Prof.