The Lawn Below the Royal Crescent Ha-Ha, Bath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Time Team to Archaeology for All

From Time Team to Archaeology for All Dr Carenza Lewis University of Cambridge www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk Enhancing educational, economic and social well-being through active participation in archaeology. Higher Education Field Academy) Aim – To help widen participation in higher education through participation in archaeological excavation • Find out more about university • Contribute to university research • Develop confidence and deploy skills for life, learning and employment The first HEFA - Terrington 2005 “I really enjoyed it. The best bit was not knowing what we would find’ (NP) “It was hard work but I had a great time” (MS). “The kids were really enthusiastic, talking about it all the way home, asking questions…. It helps that they’re doing it themselves, not just watching” (SC) “All the students loved their experiences and are still talking about it! It was judged much ‘cooler’ than going to Alton Towers!” (EO). Coxwold Castleton Wiveton Binham Terrington St Hindringham Clement Gaywood Peakirk Acle Wisbech St Ufford Mary Castor Thorney Carleton Rode Sawtry Ramsey Isleham Garboldisham Chediston Houghton Willingham Cottenham Rampton Hessett Walberswick Riseley Swaffham Coddenham Girton Bulbeck Warnborough Great Long Sharnbrook Shelford Stapleford Bramford Shefford Melford Ashwell 2005 Pirton 2006 Manuden Thorrington Little Hallingbury 2007 West Mersea Mill Green 2008 Amwell 2009 Writtle 2010 N Daws Heath 2011 2012 0 miles 50 2013 2014 HEFA weather! WRI/13 HEFA teams, HEFA spirit -

Nfl Releases Tight Ends and Offensive Linemen to Be Named Finalists for the ‘Nfl 100 All-Time Team’

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Alex Riethmiller – 310.840.4635 NFL – 12/9/19 [email protected] NFL RELEASES TIGHT ENDS AND OFFENSIVE LINEMEN TO BE NAMED FINALISTS FOR THE ‘NFL 100 ALL-TIME TEAM’ 18 Offensive Linemen and 5 Tight Ends to be Named to All-Time Team Episode 4 of ‘NFL 100 All-Time Team’ Airs on Friday, December 13 at 8:00 PM ET on NFL Network Following the reveal of the defensive back and specialist All-Time Team class last week, the NFL is proud to announce the 40 offensive linemen (16 offensive tackles; 15 guards; 9 centers) and 12 tight ends that are finalists for the NFL 100 All-Time Team. 39 of the 40 offensive linemen finalists have been enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The 12 finalists at tight end include eight Pro Football Hall of Famers and combine for 711 career receiving touchdowns. Episode three will also reveal four head coaches to make the NFL 100 All-Time Team. The NFL100 All-Time Team airs every Friday at 8:00 PM ET through Week 17 of the regular season. Rich Eisen, Cris Collinsworth and Bill Belichick reveal selections by position each week, followed by a live reaction show hosted by Chris Rose immediately afterward, exclusively on NFL Network. From this group of finalists, the 26-person blue-ribbon voting panel ultimately selected seven offensive tackles, seven guards, four centers and five tight ends to the All-Time Team. The NFL 100 All-Time Team finalists at the offensive tackle position are: Player Years Played Team(s) Bob “The Boomer” Brown 1964-1968; 1969-1970; 1971- Philadelphia Eagles; Los Angeles 1973 Rams; Oakland Raiders Roosevelt Brown 1953-1965 New York Giants Lou Creekmur 1950-1959 Detroit Lions Dan Dierdorf 1971-1983 St. -

The American Lawn: Culture, Nature, Design and Sustainability

THE AMERICAN LAWN: CULTURE, NATURE, DESIGN AND SUSTAINABILITY _______________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University _______________________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Landscape Architecture _______________________________________________________________________________ by Maria Decker Ghys May 2013 _______________________________________________________________________________ Accepted by: Dr. Matthew Powers, Committee Chair Dr. Ellen A. Vincent, Committee Co-Chair Professor Dan Ford Professor David Pearson ABSTRACT This was an exploratory study examining the processes and underlying concepts of design nature, and culture necessary to discussing sustainable design solutions for the American lawn. A review of the literature identifies historical perceptions of the lawn and contemporary research that links lawns to sustainability. Research data was collected by conducting personal interviews with green industry professionals and administering a survey instrument to administrators and residents of planned urban development communi- ties. Recommended guidelines for the sustainable American lawn are identified and include native plant usage to increase habitat and biodiversity, permeable paving and ground cover as an alternative to lawn and hierarchical maintenance zones depending on levels of importance or use. These design recommendations form a foundation -

Mick Aston Archaeology Fund Supported by Historic England and Cadw

Mick Aston Archaeology Fund Supported by Historic England and Cadw Mick Aston’s passion for involving people in archaeology is reflected in the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund. His determination to make archaeology publicly accessible was realised through his teaching, work on Time Team, and advocating community projects. The Mick Aston Archaeology Fund is therefore intended to encourage voluntary effort in making original contributions to the study and care of the historic environment. Please note that the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund is currently open to applicants carrying out work in England and Wales only. Historic Scotland run a similar scheme for projects in Scotland and details can be found at: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/index/heritage/grants/grants-voluntary-sector- funding.htm. How does the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund work? Voluntary groups and societies, but also individuals, are challenged to put forward proposals for innovative projects that will say something new about the history and archaeology of local surroundings, and thus inform their future care. Proposals will be judged by a panel on their intrinsic quality, and evidence of capacity to see them through successfully. What is the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund panel looking for? First and foremost, the panel is looking for original research. Awards can be to support new work, or to support the completion of research already in progress, for example by paying for a specific piece of analysis or equipment. Projects which work with young people or encourage their participation are especially encouraged. What can funding be used for? In principle, almost anything that is directly related to the actual undertaking of a project. -

North East Darlington

Archaeological Investigations Project 2008 Evaluations North East Darlington Darlington UA (C.55.1253/2008) NZ31311556 Parish: Haughton-le-Skerne Postal Code: DL1 2UF RED HALL MOAT, HAUGHTON-LE-SKERNE Red Hall Moat, Haughton-le-Skerne. Final Report for an Archaeological Evaluation Farmer, I Newcastle upon Tyne : Ian Farmer Associates, 2008, 39pp, colour pls, figs, refs Work undertaken by: Ian Farmer Associates The evaluation consisted of two trenches either side of the 1980s play area and a single pit centrally located within its southern boundary. Both trenches revealed medieval/post- medieval deposits and artefacts. Trench 2 revealed a medieval stone spread. A modern tramline feature, likely to be associated with the construction of the play area, extended across the whole of Pit 1. [Au(abr)] SMR primary record number: 31232 Archaeological periods represented: MO, MD, PM OASIS ID: ianfarme1-50757 (C.55.1254/2008) NZ34601330 Parish: Middleton St. George Postal Code: DL2 1DY MIDDLETON AIRPORT TRANSFER SCHEME, MIDDLETON ST. GEORGE Middleton Airport Transfer Scheme, Middleton St. George, County Durham. An Archaeological Evaluation Geck, S South Shields : Tyne & Wears Museum Archaeology Department, Report: 845 2008, 22pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Tyne & Wears Museum Archaeology Department No archaeological features were observed within the evaluation trenches. [Au(adp)] SMR primary record number: 24071 OASIS ID: tyneandw3-46033 (C.55.1255/2008) NZ22771715 Parish: High Coniscliffe Postal Code: DL2 2LT ULNABY HALL, HIGH CONISCLIFFE Ulnaby Hall, High Coniscliffe, County Durham. Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Hall, N Salisbury : Wessex Archaeology, Report: 68731 2008, 37pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Wessex Archaeology An archaeological evaluation was carried out by Channel 4's "Time Team", at the site of the Scheduled Ulnaby deserted medieval settlement. -

Proposed Archaeological Evaluation at Syndale Park, Ospringe, Kent

Zinch House, Station Road, Stogumber, Somerset Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of the Results OS 1840 Tithe map showing Zinch House Ref: 52568.14 Wessex Archaeology October 2003 ZINCH HOUSE, STATION ROAD, STOGUMBER, TAUNTON, SOMERSET ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT OF THE RESULTS Document Ref. 52568.14 Prepared for: Wildfire Television Limited 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON W12 8QP By: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB October 2003 © Copyright The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited 2003, all rights reserved The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited, Registered Charity No. 287786 ZINCH HOUSE, STATION ROAD, STOGUMBER, TAUNTON, SOMERSET ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT OF THE RESULTS Contents Summary .......................................................................................................4 Acknowledgements.......................................................................................5 1 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................6 1.1 The Site............................................................................................6 1.2 Previous Archaeological Work ........................................................6 2 METHODS .....................................................................................7 2.1 Introduction ......................................................................................7 2.2 Aims and Objectives ........................................................................7 -

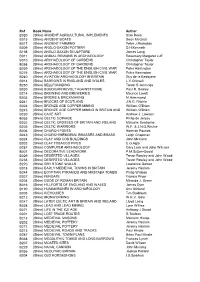

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

Designing Parterres on the Main City Squares

https://doi.org/10.24867/GRID-2020-p66 Professional paper DESIGNING PARTERRES ON THE MAIN CITY SQUARES Milena Lakićević , Ivona Simić , Radenka Kolarov University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Agriculture, Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Novi Sad, Serbia Abstract: A “parterre” is a word originating from the French, with the meaning interpreted as “on the ground”. Nowadays, this term is widely used in landscape architecture terminology and depicts a ground- level space covered by ornamental plant material. The designing parterres are generally limited to the central city zones and entrances to the valuable architectonic objects, such as government buildings, courts, museums, castles, villas, etc. There are several main types of parterres set up in France, during the period of baroque, and the most famous one is the parterre type “broderie” with the most advanced styling pattern. Nowadays, French baroque parterres are adapted and communicate with contemporary landscape design styles, but some traits and characteristics of originals are still easily recognizable. In this paper, apart from presenting a short overview of designing parterres in general, the main focus is based on designing a new parterre on the main city square in the city of Bijeljina in the Republic of Srpska. The design concept relies on principles known in the history of landscape art but is, at the same time, adjusted to local conditions and space purposes. The paper presents the current design of the selected zone – parterre on the main city square in Bijeljina and proposes a new design strongly influenced by the “broderie” type of parterre. For creating a new design proposal we have used the following software AutoCad (for 2D drawings) and Realtime Landscaping Architect (for more advanced presentations and 3D previews). -

The Early Medieval Period, Its Main Conclusion Is They Were Compiled at Malmesbury

Early Medieval 10 Early Medieval Edited by Chris Webster from contributions by Mick Aston, Bruce Eagles, David Evans, Keith Gardner, Moira and Brian Gittos, Teresa Hall, Bill Horner, Susan Pearce, Sam Turner, Howard Williams and Barbara Yorke 10.1 Introduction raphy, as two entities: one “British” (covering most 10.1.1 Early Medieval Studies of the region in the 5th century, and only Cornwall by the end of the period), and one “Anglo-Saxon” The South West of England, and in particular the three (focusing on the Old Sarum/Salisbury area from the western counties of Cornwall, Devon and Somerset, later 5th century and covering much of the region has a long history of study of the Early Medieval by the 7th and 8th centuries). This is important, not period. This has concentrated on the perceived “gap” only because it has influenced past research questions, between the end of the Roman period and the influ- but also because this ethnic division does describe (if ence of Anglo-Saxon culture; a gap of several hundred not explain) a genuine distinction in the archaeological years in the west of the region. There has been less evidence in the earlier part of the period. Conse- emphasis on the eastern parts of the region, perhaps quently, research questions have to deal less with as they are seen as peripheral to Anglo-Saxon studies a period, than with a highly complex sequence of focused on the east of England. The region identi- different types of Early Medieval archaeology, shifting fied as the kingdom of Dumnonia has received detailed both chronologically and geographically in which issues treatment in most recent work on the subject, for of continuity and change from the Roman period, and example Pearce (1978; 2004), KR Dark (1994) and the evolution of medieval society and landscape, frame Somerset has been covered by Costen (1992) with an internally dynamic period. -

The Time Team Guide to the History of Britain Free

FREE THE TIME TEAM GUIDE TO THE HISTORY OF BRITAIN PDF Tim Taylor | 320 pages | 05 Jul 2010 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9781905026708 | English | London, United Kingdom The Time Team Guide to the History of Britain by Tim Taylor Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. We all know that the Battle of Hastings was fought inLondon's 'one big burning blaze' tore through the capital in and that Britain declared war on Nazi Germany inbut many of us remember the most important moments in our history by the folk stories which are attached to them. So we remember Henry VIII for his wives rather than the Reformation The Time Team Guide to the History of Britain Charles We all know that the Battle of Hastings was fought inLondon's 'one big burning blaze' tore through the capital in and that Britain declared war on Nazi Germany inbut many of us remember the most important moments in our history by the folk stories which are attached to them. But if we set aside these stories, do we really know what happened when, and why it's so important? Which came first, the Bronze Age or the Stone Age? Why did the Romans play such a significant role in our past? And how did a nation as small as Britain come to command such a vast empire? Here, Tim Taylor and the team of expert historians behind Channel 4's Time Team, answer these questions and many more, cataloguing British history in a way that is accessible to all. -

Home Landscape Planning Worksheet: 12 Steps to a Functional Design

Home Landscape Planning Worksheet: 12 steps to a functional design This worksheet will guide you through the process of Gather information designing a functional landscape plan. The process includes these steps: Step 1. Make a scale drawing • Gather information about the site and who will use it. Landscape designs are generally drawn from a bird’s- • Prioritize needs and wants. eye view in what designers call “plan view.” To prepare a base map (scale drawing) of your property use graph • Consider maintenance requirements. paper and let one square equal a certain number of feet • Determine a budget. (e.g. 1 square = 2 feet), or draw it to scale using a ruler • Organize the landscape space. or scale (e.g. 1 inch = 8 feet). • Determine the shape of the spaces and how they The base map should include these features: relate to each other. • Scale used • Select the plants that will fi ll the landscape. • North directional arrow • Property lines Base Map and Initial Site Analysis (not to scale) You may want to make several photocopies of this base map to use for the following steps in the design process. Step 2. Site analysis A thorough site analysis tells you what you have to work NICE VIEW with on the property. Part 1 of the “Home Landscape Questionnaire” (see insert) includes questions that NEED PRIVACY should be answered when completing a site analysis. Lay a piece of tracing paper over the base map and draw the information gathered during the site analysis. This layer should include these features: KITCHEN/ DINING ROOM • Basic drainage patterns -

Proposed Archaeological Evaluation at Syndale Park, Ospringe, Kent

Syndale Park, Ospringe, Kent Archaeological Evaluation and an Assessment of the Results Ref: 52568.01 Wessex Archaeology May 2003 SYNDALE PARK, OSPRINGE, KENT AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION AND AN ASSESSMENT OF THE RESULTS Document Ref. 52568.01 May 2003 Prepared for: Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON SW1 8QP By: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB © Copyright The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited 2003, all rights reserved The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited, Registered Charity No. 287786 1 SYNDALE PARK, OSPRINGE, KENT AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION AND AN ASSESSMENT OF THE RESULTS Contents Summary..................................................................................................................4 Acknowledgements..................................................................................................5 1 BACKGROUND............................................................................................6 1.1 Description of the site.....................................................................................6 1.2 Previous archaeological work .......................................................................6 2 METHODS.....................................................................................................8 2.1 Introduction....................................................................................................8 2.2 Aims and objectives .......................................................................................8