Dialectic and Definition in Aristotle's Topics May Sim Oklahoma State University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play, and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 8-2012 The idea of mimesis: Semblance, play, and critique in the works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno Joseph Weiss DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Weiss, Joseph, "The idea of mimesis: Semblance, play, and critique in the works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno" (2012). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 125. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/125 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play, and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy October, 2011 By Joseph Weiss Department of Philosophy College of Liberal Arts and Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois 2 ABSTRACT Joseph Weiss Title: The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno Critical Theory demands that its forms of critique express resistance to the socially necessary illusions of a given historical period. Yet theorists have seldom discussed just how much it is the case that, for Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. -

Art As a Form of Negative Dialectics: 'Theory' in Adorno's Aesthetic Theory Author(S): WILLIAM D

Art as a Form of Negative Dialectics: 'Theory' in Adorno's Aesthetic Theory Author(s): WILLIAM D. MELANEY Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, New Series, Vol. 11, No. 1 (1997), pp. 40-52 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25670205 . Accessed: 10/12/2011 23:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Speculative Philosophy. http://www.jstor.org WILLIAM D. MELANEY Art as a Form ofNegative Dialectics: Theory' inAdorno's Aesthetic Theory Adorno's dialectical approach to aesthetics is inseparable from his concep as a tion of art socially and historically consequential source of truth.None theless, his dialectical approach to aesthetics is perhaps understood better in terms of his monumental work, Aesthetic Theory (1984), which attempts to relate the speculative tradition in philosophical aesthetics to the situation of art in twentieth-century society, than in terms of purely theoretical claims. In an effort to clarify his aesthetic position, I hope to demonstrate both that Adorno embraces theKantian thesis concerning art's autonomy and that he criticizes transcendental philosophy. -

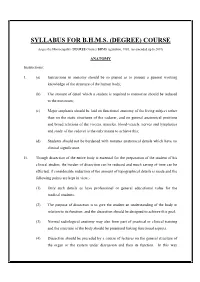

Syllabus for B.H.M.S. (Degree) Course

SYLLABUS FOR B.H.M.S. (DEGREE) COURSE As per the Homoeopathy (DEGREE Course) BHMS regulation, 1983, (as amended up to 2019) ANATOMY Instructions: I. (a) Instructions in anatomy should be so planed as to present a general working knowledge of the structure of the human body; (b) The amount of detail which a student is required to memorise should be reduced to the minimum; (c) Major emphasis should be laid on functional anatomy of the living subject rather than on the static structures of the cadaver, and on general anatomical positions and broad relations of the viscera, muscles, blood-vessels, nerves and lymphatics and study of the cadaver is the only means to achieve this; (d) Students should not be burdened with minutes anatomical details which have no clinical significance. II. Though dissection of the entire body is essential for the preparation of the student of his clinical studies, the burden of dissection can be reduced and much saving of time can be effected, if considerable reduction of the amount of topographical details is made and the following points are kept in view:- (1) Only such details as have professional or general educational value for the medical students. (2) The purpose of dissection is to give the student an understanding of the body in relation to its function, and the dissection should be designed to achieve this goal. (3) Normal radiological anatomy may also form part of practical or clinical training and the structure of the body should be presented linking functional aspects. (4) Dissection should be preceded by a course of lectures on the general structure of the organ or the system under discussion and then its function. -

Hegel: Three Studies I Theodor W

Hegel Three Studies · I Hegel Three Studies Theodor W. Adorno. translated by Shierry Weber Nicholsen with an introduction by Shierry Weber Nicholsen and Jeremy]. Shapiro \\Imi\�\\�\i\il\"t�m .� . 39001101483082 The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England ·" '.�. This edition © 1993 Massachusetts Institute of Technology This work originally appeared in German under the title Drei Studien zu Hegel, © 1963, 1971 Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, Germany. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any fo rm or by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Baskerville by The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Adorno, Theodor W., 1903-1969. [Drei Studien zu Hegel. English] Hegel: three studies I Theodor W. Adorno ; translated by Shierry Weber Nicholsen ; with an introduction by Shierry Weber Nicholsen and Jeremy J. Shapiro. p. cm.-(Studies in contemporary German social thought) Translation of: Drei Studien zu Hegel. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01131-X 1. Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, 1770- 1831. 1. Title. 11. Series. B2948.A3213 1993 193----dc20 92-23161 CIP ..�. •. , ......... ..,..·...",...,..'''_''e ... • 11�. I },i . :-::" 7.�� <,f,' · '�: · : :-:- ;;· �:<" For Karl Heinz Haag 337389 Contents Introduction by Shierry Weber Nicholsen and IX Jeremy J. Shapiro Preface XXXv A Note on the Text xxxvii Editorial Remarks from the German Edition XXXIX Aspects of Hegel's Philosophy 1 The Experiential Content of Hegel's Philosophy 53 Skoteinos, or How to Read Hegel 89 Notes 149 Name Index 159 Introduction Shierry Weber Nicholsen Jeremy J. -

The Beginnings of Formal Logic: Deduction in Aristotle's Topics Vs

Phronesis 60 (�0�5) �67-309 brill.com/phro The Beginnings of Formal Logic: Deduction in Aristotle’s Topics vs. Prior Analytics Marko Malink Department of Philosophy, New York University, 5 Washington Place, New York, NY 10003. USA [email protected] Abstract It is widely agreed that Aristotle’s Prior Analytics, but not the Topics, marks the begin- ning of formal logic. There is less agreement as to why this is so. What are the distinctive features in virtue of which Aristotle’s discussion of deductions (syllogismoi) qualifies as formal logic in the one treatise but not in the other? To answer this question, I argue that in the Prior Analytics—unlike in the Topics—Aristotle is concerned to make fully explicit all the premisses that are necessary to derive the conclusion in a given deduction. Keywords formal logic – deduction – syllogismos – premiss – Prior Analytics – Topics 1 Introduction It is widely agreed that Aristotle’s Prior Analytics marks the beginning of formal logic.1 Aristotle’s main concern in this treatise is with deductions (syllogismoi). Deductions also play an important role in the Topics, which was written before the Prior Analytics.2 The two treatises start from the same definition of what 1 See e.g. Cornford 1935, 264; Russell 1946, 219; Ross 1949, 29; Bocheński 1956, 74; Allen 2001, 13; Ebert and Nortmann 2007, 106-7; Striker 2009, p. xi. 2 While the chronological order of Aristotle’s works cannot be determined with any certainty, scholars agree that the Topics was written before the Prior Analytics; see Brandis 1835, 252-9; Ross 1939, 251-2; Bocheński 1956, 49-51; Kneale and Kneale 1962, 23-4; Brunschwig 1967, © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���5 | doi �0.��63/�5685�84-��34��86 268 Malink a deduction is (stated in the first chapter of each). -

1 the Aristotelian Method and Aristotelian

1 The Aristotelian Method and Aristotelian Metaphysics TUOMAS E. TAHKO (www.ttahko.net) Published in Patricia Hanna (Ed.), An Anthology of Philosophical Studies (Athens: ATINER), pp. 53-63, 2008. ABSTRACT In this paper I examine what exactly is ‘Aristotelian metaphysics’. My inquiry into Aristotelian metaphysics should not be understood to be so much con- cerned with the details of Aristotle's metaphysics. I am are rather concerned with his methodology of metaphysics, although a lot of the details of his meta- physics survive in contemporary discussion as well. This warrants an investigation into the methodological aspects of Aristotle's metaphysics. The key works that we will be looking at are his Physics, Meta- physics, Categories and De Interpretatione. Perhaps the most crucial features of the Aristotelian method of philosophising are the relationship between sci- ence and metaphysics, and his defence of the principle of non-contradiction (PNC). For Aristotle, natural science is the second philosophy, but this is so only because there is something more fundamental in the world, something that natural science – a science of movement – cannot study. Furthermore, Aristotle demonstrates that metaphysics enters the picture at a fundamental level, as he argues that PNC is a metaphysical rather than a logical principle. The upshot of all this is that the Aristotelian method and his metaphysics are not threatened by modern science, quite the opposite. Moreover, we have in our hands a methodology which is very rigorous indeed and worthwhile for any metaphysician to have a closer look at. 2 My conception of metaphysics is what could be called ‘Aristotelian’, as op- posed to Kantian. -

MARXISM and the ENGELS PARADOX Jeff Coulter Introduction

MARXISM AND THE ENGELS PARADOX Jeff Coulter Introduction FOR MARXIST philosophy, in so far as it still forms an independent reflection upon the concepts that inform a Marxist practice, dialectics involves the conscious interception of the object in its process of developmentY1where the object is man's production of history. The ultimate possibility of human self-liberation is grounded in the postu- late that man is a world-producing being. For Hegel, from whom Marx derived the dialectic, philosophy remained a speculative affair, a set of ideas remote from human praxis. Marx sought to actualize the philosophical interception as a practical interception, to abolish concretely the historical alienation of man from his species nature, an alienation viewed speculatively by the Helgelians. In the practical abolition of historical alienation, philosophy as the expression of abstract propositions pertaining to the human condition would also be abolished. In the formulation adduced by Friedrich Engels, however, dialectics are situated prior to the anthropological dimension. A set of static tenets drawn from Hegelian metaphysics, they are "located" in physi- cal nature. It is the purpose of this paper to investigate what Gustav Wetter has described as "the curse put upon the dialectic by its trans- ference to the realm of Nat~re."~ This problem has been discussed before by non-Marxist writers.' The main reason for the present approach is that it endeavours to assess the relationship of Marxism to science from within a Marxist perspective, and it further attempts to demonstrate some of the con- sequences for Marxist philosophy that arise out of a commitment to what I term the "Engels paradox". -

Metaphysics Translated by W

Aristotle Metaphysics translated by W. D. Ross Book Α 1 All men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses; for even apart from their usefulness they are loved for themselves; and above all others the sense of sight. For not only with a view to action, but even when we are not going to do anything, we prefer seeing (one might say) to everything else. The reason is that this, most of all the senses, makes us know and brings to light many differences between things. By nature animals are born with the faculty of sensation, and from sensation memory is produced in some of them, though not in others. And therefore the former are more intelligent and apt at learning than those which cannot remember; those which are incapable of hearing sounds are intelligent though they cannot be taught, e.g. the bee, and any other race of animals that may be like it; and those which besides memory have this sense of hearing can be taught. The animals other than man live by appearances and memories, and have but little of connected experience; but the human race lives also by art and reasonings. Now from memory experience is produced in men; for the several memories of the same thing produce finally the capacity for a single experience. And experience seems pretty much like science and art, but really science and art come to men through experience; for ‘experience made art’, as Polus says, ‘but inexperience luck.’ Now art arises when from many notions gained by experience one universal judgement about a class of objects is produced. -

Greco-Roman Legal Analysis: the Topics of Invention

St. John's Law Review Volume 66 Number 1 Volume 66, Winter 1992, Number 1 Article 3 Greco-Roman Legal Analysis: The Topics of Invention Michael Frost Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GRECO-ROMAN LEGAL ANALYSIS: THE TOPICS OF INVENTION MICHAEL FROST* I. INTRODUCTION Despite a wealth of commentary on legal reas6ning and legal logic, modern writers on the subject demonstrate a curious and re- grettable disregard for the close connections between classical Greco-Roman theories of forensic discourse and modern theories of legal reasoning and analysis. Two recent treatises on logic and legal reasoning, Judge Ruggero Aldisert's Logic for Lawyers' and Pro- fessor Steven Burton's An Introduction to Law and Legal Reason- ing,2 are exceptions to this rule. Their treatises fall within a 2,000- year-old tradition of rhetorical analysis and discourse especially designed for lawyers. Beginning with treatises on rhetoric by Aris- totle, Cicero, and Quintilian, philosophers and lawyers have re- peatedly attempted, some more ambitiously than others, to de- scribe and analyze legal reasoning and methodology. Judge Aldisert implicitly acknowledges his participation in this ancient tradition with an epigraph drawn from Cicero's Republic, with his choice of subject matter, and with his use of centuries-old rhetori- cal terminology.3 Professor Burton's approach to legal analysis and argument can also be traced back to ancient rhetorical treatises especially written for the instruction of beginning advocates. -

Aristotle on Sign-Inference and Related Forms Ofargument

12 Introduction degree oflogical sophistication about what is required for one thing to follow from another had been achieved. The authorities whose views are reported by Philodemus wrote to answer the charges of certain unnamed opponents, usually and probably rightly supposed to be Stoics. These opponents draw· on the resources of a logical STUDY I theory, as we can see from the prominent part that is played in their arguments by an appeal to the conditional (auvTJp.p.EvOV). Similarity cannot, they maintain, supply the basis of true conditionals of the Aristotle on Sign-inference and kind required for the Epicureans' inferences to the rion-evident. But instead of dismissing this challenge, as Epicurus' notoriously Related Forms ofArgument contemptuous attitude towards logic might have led us to expect, the Epicureans accept it and attempt· to show that similarity can THOUGH Aristotle was the first to make sign-inference the object give rise to true conditionals of the required strictness. What is oftheoretical reflection, what he left us is less a theory proper than a more, they treat inference by analogy as one of two species of argu sketch of one. Its fullest statement is found in Prior Analytics 2. 27, ment embraced by the method ofsimilarity they defend. The other the last in a sequence offive chapters whose aim is to establish that: is made up of what we should call inductive arguments or, if we .' not only are dialectical and demonstrative syllogisms [auAAoyw,uol] effected construe induction more broadly, an especially prominent special by means of the figures [of the categorical syllogism] but also rhetorical case of inductive argument, viz. -

The Use of Animals in Higher Education

THE USE OF P R O B L E M S, A L T E R N A T I V E S , & RECOMMENDA T I O N S HUMANE SOCIETY PR E S S by Jonathan Balcombe, Ph.D. PUBLIC PO L I C Y SE R I E S Public Policy Series THE USE OF An i m a l s IN Higher Ed u c a t i o n P R O B L E M S, A L T E R N A T I V E S , & RECOMMENDA T I O N S by Jonathan Balcombe, Ph.D. Humane Society Press an affiliate of Jonathan Balcombe, Ph.D., has been associate director for education in the Animal Res e a r ch Issues section of The Humane Society of the United States since 1993. Born in England and raised in New Zealand and Canada, Dr . Balcombe studied biology at York University in Tor onto before obtaining his masters of science degree from Carleton University in Ottawa and his Ph.D. in ethology at the University of Tennessee. Ack n ow l e d g m e n t s The author wishes to thank Andrew Rowan, Martin Stephens, Gretchen Yost, Marilyn Balcombe, and Francine Dolins for reviewing and commenting on earlier versions of this monograph. Leslie Adams, Kathleen Conlee, Lori Do n l e y , Adrienne Gleason, Daniel Kos s o w , and Brandy Richardson helped with various aspects of its research and preparation. Copyright © 2000 by The Humane Society of the United States. -

Aristotle-Rhetoric.Pdf

Rhetoric Aristotle (Translated by W. Rhys Roberts) Book I 1 Rhetoric is the counterpart of Dialectic. Both alike are con- cerned with such things as come, more or less, within the general ken of all men and belong to no definite science. Accordingly all men make use, more or less, of both; for to a certain extent all men attempt to discuss statements and to maintain them, to defend themselves and to attack others. Ordinary people do this either at random or through practice and from acquired habit. Both ways being possible, the subject can plainly be handled systematically, for it is possible to inquire the reason why some speakers succeed through practice and others spontaneously; and every one will at once agree that such an inquiry is the function of an art. Now, the framers of the current treatises on rhetoric have cons- tructed but a small portion of that art. The modes of persuasion are the only true constituents of the art: everything else is me- rely accessory. These writers, however, say nothing about en- thymemes, which are the substance of rhetorical persuasion, but deal mainly with non-essentials. The arousing of prejudice, pity, anger, and similar emotions has nothing to do with the essential facts, but is merely a personal appeal to the man who is judging the case. Consequently if the rules for trials which are now laid down some states-especially in well-governed states-were applied everywhere, such people would have nothing to say. All men, no doubt, think that the laws should prescribe such rules, but some, as in the court of Areopagus, give practical effect to their thoughts 4 Aristotle and forbid talk about non-essentials.