The Hi !Am Ec Agic Lt Mics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ground Water Scenario of Lakhimpur Kheri District, Up

GROUND WATER SCENARIO OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. (A.A.P.: 2012-2013) By Dr. D.S. Pandey Scientist 'D' CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................2 I. INTRODUCTION ..................5 II. CLIMATE & RAINFALL ..................5 III. GEOMORPHOLOGY & SOIL TYPES ..................6 IV. GROUND WATER SCENARIO ..................6 V. GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ..................8 VI. GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUE AND PROBLEMS ..................9 VII. MASS AWARENESS PROGRAMME ..................9 PLATES: I. INDEX MAP OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. II. PRE-MONSOON DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL MAP (MAY, 2012) OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. III. POST-MONSOON DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL MAP (NOV. 2012) OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. IV. DYNAMIC GROUND WATER RESOURCES OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. V. GROUND WATER USER MAP, LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. VI. ARSENIC AFFECTED AREA OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. VII. Exploratory Tubewells (C.G.W.B.) For Arsenic Studies DISTRICT AT GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) : 7680.00 ii. Administrative Divisions (as on 31.3.2005) Number of Blocks : 6/15 Number of Panchayat Villages : 1829 iii. Population (as on 2001 census) : 32,07,234 iv. Average Annual Rainfall (mm) : 1093.50 mm 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic Units : Older & Younger Alluvium Major Drainages : Gomati & Ghaghra 3. LAND USE (Sq. Km.) a) Forest area (Sq. Km.) : 2321.54 b) Net area sown (Sq. Km.) : 4863.82 c) Cultivable area (Sq. Km.) : 4863.82 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES : Sandy Loam 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS (as on 2004-05) : 6984.20 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (Areas and Number of Structures) (Sq.Km.) Dugwells : 168 Tubewells / Borewells : 713 state tubewells & 108430 Private tubewells Canals : 641 Km. -

Basic Data Report of Kaliandi- Vihar Exploratory Tube

GROUND WATER SCENARIO OF SHRAVASTI DISTRICT, UTTAR PRADESH By S. MARWAHA Superintending. Hydrogeologist CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................3 I. INTRODUCTION ..................5 II. CLIMATE & RAINFALL ..................5 III. GEOMORPHOLOGY & SOILS ..................6 IV. HYDROGEOLOGY ..................7 V. GROUND WATER RESOURCES & ESTIMATION ..................11 VI. GROUND WATER QUALITY ..................13 VII. GROUND WATER DEVELOPMENT ..................16 VIII. GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ..................17 IX. AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITY ..................18 X. AREAS NOTIFIED BY CGWA/SGWA ..................18 XI. RECOMMENDATIONS ..................18 TABLES : 1. Land Utilisation of Shravasti district (2008-09) 2. Source-wise area under irrigation (Ha), Shravasti, UP 3. Block-wise population covered by hand pumps, Shravasti, UP 4. Depth to water levels - Shravasti district 5. Water Level Trend Of Hydrograph Stations Of Shravasti District, U.P. 6. Block Wise Ground Water Resources As On 31.3.2009, Shravasti 7. Constituent, Desirable Limit, Permissible Limit Number Of Samples Beyond Permissible Limit & Undesirable Effect Beyond Permissible Limit 8. Chemical Analysis Result Of Water Samples, 2011, Shravasti District, U.P 9. Irrigation Water Class & Number of Samples, Shravasti District, U.P 10. Block wise Ground water Extraction structures, 2009, Shravasti, U.P PLATES : (I) Hydrogeological Map Of Shravasti District, U.P. (II) Depth To Water Map (Pre-Monsoon, 2012), Shravasti District, U.P. (III) Depth To Water Map (Post-Monsoon, 2012) , Shravasti District, U.P. (IV) Water Level Fluctuation Map (Pre-Monsoon, 2012—Post-Monsoon,2012), Shravasti District, U.P. (V) Ground Water Resources, as on 31.3.2009, Shravasti District, U.P. 2 DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) : 1858 ii. -

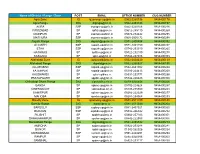

Copy of PSC Address.Xlsx

Address of Program Study Centers S.N Districts Name of Institutes Address Contact No 1 Agra District Women Hospital-Agra Shahid Bhagatsingh Rd, Rajamandi Crossing, Bagh Muzaffar 0562 226 7987 Khan, Mantola, Agra, Uttar Pradesh 282002 2Aligarh District Women Hospital-Aligarh Rasal Ganj Rd, City, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh 202001 3 Pt. DDU District Combined Hospital-Aligarh Ramghat Rd, Near Commissioner House, Quarsi, Aligarh, 0571 274 1446 Uttar Pradesh 202001 4 Prayagraj District Women Hospital-Prayagraj 22/26, Kanpur - Allahabad Hwy, Roshan Bagh, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh 211003 5 Azamgarh District Women Hospital-Azamgarh Deen Dayal Upadhyay Marg, Balrampur, Harra Ki Chungi, 091208 49999 Sadar, Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh 276001 6 Bahraich District Male Hospital-Bahraich Ghasiyaripura, Friganj, Bahraich, Uttar Pradesh 271801 094150 36818 7 Bareilly District Women Hospital-Bareilly Civil Lines, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh 243003 0581 255 0009 8 Basti District Women Hospital-Basti Ladies hospital, Kateshwar Pur, Basti, Uttar Pradesh 272001 9 Gonda District Women Hospital-Gonda Khaira, Gonda, Uttar Pradesh 271001 11 Etawah District Male Hospital-Etawah Civil Lines, Etawah, Uttar Pradesh 206001 099976 04403 12 Ayodhya District Women Hospital-Ayodhya Fatehganj Rikabganj Road, Rikaabganj, Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh 224001 13 GB Nagar Combined Hospital-GB Nagar C-18, Service Rd, C-Block, Sector 31, Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201301 14 Ghaziabad District Combined Hospital, Sanjay Nagar- District Combined Hospital, Mansi Vihar, Sector 23, Sanjay Ghaziabad Nagar, Ghaziabad, -

Officers Office/Home Mobile Number Health Department

S.No Officers Office/Home Mobile Number 1 District Magistrate 232815/232401 9454417535 2 Chief Revenue Officer 9454416032 3 Additional District Magistrate 232063/232419 9454417606 4 City Magistrate 232897/232654 9454416037 5 Settlement Officer Consolidation 233269 9452512381 6 A.I.G. Stamp 238653 9451724627 7 Senior Treasury Officer 232894 9415194051 8 Deputy Director Consolidation 9454416032 9 S D M , Kaiserganj 254014 9454416035 10 S D M , Nanpara 232211 9454416034 11 S D M , Mahasi 262280 9454416036 12 S D M , Mihinpurwa 9454416051 13 S D M , Payagpur 9454416050 14 Extra Magistrate 9454416043 15 Tehsildar,Bahraich 232885 9454416038 16 Tehsildar Judicial,Bahraich 9454719467 17 Nayab Tehsildar,Mahasi 9450910592 18 Tehsildar,Nanpara 232203 9454416039 19 Nayab Tehsildar,Mihinpurwa 9839644750 20 Nayab Tehsildar,Risia 9838141541 21 Tehsildar,Kaiserganj 254008 9454416040 22 Nayab Tehsildar,Kaiserganj 9454416045 23 Nayab Tehsildar,Jarwal 9454416051 24 Tehsildar,Mahasi 262281 9454416014 25 Nayab Tehsildar,Tejwapur 9454416050 26 Tehsildar , Mihinpurwa 9454416045 27 Tehsildar , Payagpur 9454416042 28 District Mining Officer 8004117191 Health department 25 Chief Medical Officer 232888/232417 9454455262 26 Chief Medical Suprintendent (Male) 9838771504 27 Chief Medical Suprintendent (Female) 9451086407 28 District Homeopathic Suprintendent 9453833926 29 Regional Ayurvedic Unani Medical Officer 9919130517 30 Nagar Health Officer 9415347357 31 Additional Chief Medical Officer 9919253979 32 Incharge Chief Veterinary Officer 235728 9411298565 33 Medical -

High Court of Judicature at Allahabad Notification Dated: Allahabad: August 04, 2018

HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT ALLAHABAD NOTIFICATION DATED: ALLAHABAD: AUGUST 04, 2018 No. 2879 /Admin. (Services)/2018 Sri Avinash Chandra Gautam, Additional Civil Judge (Junior Division), Faizabad is appointed U/s 11(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973 (Act No. 2 of 1974) as Judicial Magistrate, First Class, Faizabad vice Smt. Rashmi Chand. No. 2880 /Admin. (Services)/2018 Smt. Rashmi Chand, Judicial Magistrate, First Class, Faizabad to be Additional Civil Judge (Junior Division), Faizabad. No. 2881 /Admin. (Services)/2018 Smt. Tapasya Tripathi, Additional Civil Judge (Junior Division), Faizabad is appointed U/s 11(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973 (Act No. 2 of 1974) as Judicial Magistrate, First Class, Faizabad vice Smt. Shikha Yadav. No. 2882 /Admin. (Services)/2018 Smt. Shikha Yadav, Judicial Magistrate, First Class, Faizabad to be Civil Judge (Junior Division), Bahraich vice Sushri Roma Gupta. No. 2883 /Admin. (Services)/2018 Sushri Roma Gupta, Civil Judge (Junior Division), Bahraich is appointed U/s 11(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973 (Act No. 2 of 1974) as Judicial Magistrate, First Class, Bahraich vice Sri Purushottam Awasthi. No. 2884 /Admin. (Services)/2018 Sri Purushottam Awasthi, Judicial Magistrate, First Class, Bahraich to be Civil Judge (Junior Division), Kaiserganj sitting at Bahraich vice Sri Aviral Singh. No. 2885 /Admin. (Services)/2018 Sri Aviral Singh, Civil Judge (Junior Division), Kaiserganj sitting at Bahraich to be Additional Civil Judge (Junior Division), Bahraich. No. 2886 /Admin. (Services)/2018 Sri Dharmendra Kumar Yadav, Additional Civil Judge (Junior Division), Deoria to be Additional Civil Judge (Junior Division), Bahraich. No. 2887 /Admin. -

An Impact Evaluation of the Rollout of the Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Uttar Pradesh State, India

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Public Health Theses School of Public Health January 2020 An Impact Evaluation Of The Rollout Of The Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine In Uttar Pradesh State, India. 2017-2019 Elizabeth Edgerley [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ysphtdl Recommended Citation Edgerley, Elizabeth, "An Impact Evaluation Of The Rollout Of The Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine In Uttar Pradesh State, India. 2017-2019" (2020). Public Health Theses. 1933. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ysphtdl/1933 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Public Health at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Health Theses by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 An Impact Evaluation of the Rollout of the Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Uttar Pradesh State, India. 2017-2019 Author: Elizabeth Edgerley May 2020 For Consideration for the Completion of the MPH Thesis Credit 2020 Dept. of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases Committee Chair: Dr. Dan Weinberger Committee Member: Dr. Elsio Wunder 2 Abstract This paper is aimed toward examining whether methods currently being rolled out to administer the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to children in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh is effectively reducing morbidity and mortality. The fundamental question regarding this current effort is if it proves to be useful at reducing the prevalence of Streptococcus Pneumoniae and whether the surveillance methods examining the efficacy of healthcare interventions are helpful. -

District Survey Report

1. INTRODUCTION As per gazette notification dated 15th January 2016, of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, the District-Environment Impact Assessment Authority (DEIAA) to be constituted by the divisional commissioner for prior environmental clearance of quarry for minor minerals. The DEIAA will scrutinize and recommend the prior environmental clearance of ministry of minor minerals on the basis of district survey report. The main purpose of preparation of District Survey Report is to identify the mineral resources and mining activities along with other relevant data of district. This DSR contains details of Lease, Sand mining and Revenue which comes from minerals in the district and prepared on the basis of data collected from different concern departments and concern Mining Inspector. DISTRICT-SHRAVASTI Shravasti district is in the north western part of Uttar Pradesh covering an area of 1858.20 Sq. Km. It is a created district carved out from Bahraich district. Shravasti, which is closely associated with the life of Lord Buddha, shares border with Balrampur, Gonda & Bahraich districts. Bhinga is the district headquarters of Shravasti and is approximately 175 kilometers away from the state capital. The district is drained by river Rapti & its tributaries. In 2001 census, Shravasti has three Tehsils, viz., Bhinga, Jamunaha and Ikauna. Shravasti is a historically famous district of eastern Uttar Pradesh. As per 2011 census, total population of the district is 1,114,615 persons out of which 594,318 are males and 520,297 are females. The district has having 3 tehsils, 5 blocks and 536 inhabited villages. According to 2001 census, the district accounted 0.71 % of the State’s population in which male and female percentages are 0.72 and 0.69 respectively. -

District Fact Sheet Bahraich Uttar Pradesh

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare National Family Health Survey - 4 2015 -16 District Fact Sheet Bahraich Uttar Pradesh International Institute for Population Sciences (Deemed University) Mumbai 1 Introduction The National Family Health Survey 2015-16 (NFHS-4), the fourth in the NFHS series, provides information on population, health and nutrition for India and each State / Union territory. NFHS-4, for the first time, provides district-level estimates for many important indicators. The contents of previous rounds of NFHS are generally retained and additional components are added from one round to another. In this round, information on malaria prevention, migration in the context of HIV, abortion, violence during pregnancy etc. have been added. The scope of clinical, anthropometric, and biochemical testing (CAB) or Biomarker component has been expanded to include measurement of blood pressure and blood glucose levels. NFHS-4 sample has been designed to provide district and higher level estimates of various indicators covered in the survey. However, estimates of indicators of sexual behaviour, husband’s background and woman’s work, HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes and behaviour, and, domestic violence will be available at State and national level only. As in the earlier rounds, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India designated International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai as the nodal agency to conduct NFHS-4. The main objective of each successive round of the NFHS has been to provide essential data on health and family welfare and emerging issues in this area. NFHS-4 data will be useful in setting benchmarks and examining the progress in health sector the country has made over time. -

Name of District / Range / Zone POST EMAIL OFFICE NUMBER CUG

Name of District / Range / Zone POST EMAIL OFFICE NUMBER CUG NUMBER Agra Zone IG [email protected] 0562-2265736 9454400178 Agra Range DIG [email protected] 0562-2463343 9454400197 AGRA SSP [email protected] 0562-2250106 9454400246 FIROZABAD SP [email protected] 05612-285110 9454400269 MAINPURI SP [email protected] 05672-234442 9454400295 MATHURA SSP [email protected] 0565-2505172 9454400298 Aligarh Range DIG [email protected] 0571-2400404 9454400392 ALIGARH SSP [email protected] 0571-2401150 9454400247 ETAH SSP [email protected] 05742-233319 9454400265 HATHRAS SP [email protected] 05722-232100 9454400278 KASGANJ SP [email protected] 05744-247486 9454400393 Allahabad Zone IG [email protected] 0532-2424630 9454400139 Allahabad Range DIG [email protected] 0532-2260527 9454400195 ALLAHABAD SSP [email protected] 0532-2641902 9454400248 FATEHPUR SP [email protected] 05180-224413 9454400268 KAUSHAMBI SP [email protected] 05331-232771 9454400288 PRATAPGARH SP [email protected] 05342-220423 9454400300 Chitrakoot Dham Range DIG [email protected] 0519-2220538 9454400206 BANDA SP [email protected] 05192-224624 9454400257 CHITRAKOOT SP [email protected] 05198-235500 9454400263 HAMIRPUR SP [email protected] 05282-222329 9454400277 MAHOBA SP [email protected] 05281-254068 9454400293 Bareilly Zone IG [email protected] 0581-2511199 9454400140 Bareilly Range DIG [email protected] 0581-2511049 9454400204 BAREILLY SSP [email protected] 0581-2457021 9454400260 BUDAUN SSP [email protected] 05832-266342 9454400252 PILIBHIT SP [email protected] 05882-257183 9454400301 SHAHJAHANPUR SP [email protected] -

Directory of Officers - Uttar Pradesh (East) Telephone Directory of Income Tax Offices U

DIRECTORY OF OFFICERS - UTTAR PRADESH (EAST) TELEPHONE DIRECTORY OF INCOME TAX OFFICES U. P. (EAST) , LUCKNOW CHIEF COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX, LUCKNOW Name S.No. DESIGNATION ADDRESS (O) PHONE (O) FAX (O) MOBILE (Shri/Smt./Ms.) AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 - ASHOK 1 ARUN KUMAR SINGH CCIT (CCA) 0522-2233201 0522-2233210 8005445292 MARG, LUCKNOW ADDL. CIT (HQ), O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 8005445319 2 TAJINDER PAL SINGH 0522-2233202 0522-2233209 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW 0872080468 ADDL. CIT (Vig.) O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 8005445319 3 TAJINDER PAL SINGH 0522-2233203 0522-2233213 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW 0872080468 DY. CIT (HQ) Admn., AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 4 O. N. PATHAK 0522-2233204 0522-2233204 8005446100 O/o CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW DY. CIT (Judl.), O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 5 RANJAN SRIVASTAVA 0522-2233294 0522-2233294 8005445123 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW DY. CIT (Vig.), O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 6 SARAS KUMAR 0522-2233207 0522-2233207 8005445054 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW ACIT (Tech.), O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 7 G. D. SINGH 0522-2233208 0522-2233208 8005445001 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW ITO (HQ) Admn., O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 8 VIVEK NAGRATH 0522-2233206 0522-2233206 8005445321 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW ITO (HQ) / PR, O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 9 PRAJESH SRIVASTAVA 0522-2233205 0522-2233205 8005445350 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW MSTU, PRAGYA BHAWAN, DTRTI, 10 ATUL SONKAR ITO (MSTU) 0522-2720344 0522-2720344 8005445231 GOMTI NAGAR, LUCKNOW. AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 11 JYOTI SHARMA ITO (OSD) - - 9967033678 MARG, LUCKNOW AO / DDO, O/o CCIT, AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 12 ROOP SAXENA 0522-2233241 0522-2233241 8005445008 LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW AO O/o CCIT, AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 13 MUJEEB ASHRAF 0522-2233239 - 8005445011 LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW PS, O/o CCIT, AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 14 ANITA GUPTA 0522-2233201 0522-2233210 8005445010 LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW PS, O/o CCIT, AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 15 MANJU AGARWAL 0522-2233203 0522-2233213 8005445287 LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW AD (OL), O/o CCIT, RADHA KUNTI BHAWAN, 16 S. -

Allahabad Bank

ALLAHABAD BANK Central Public Information Officers Appellate Authority Sl No. Name / Designation/Address / Phone / E-mail/ Place / Office Name / Designation Address / Phone / Fax / E-mail Place / Office 1 Sri Shashikar Dayal Allahabad Bank, Zonal Office ALLAHABAD Dr. Rahul Srivastava Deputy General 22 -P, Purushottam Das Tandon Marg, ZONE Circle General Manager Manager Civil Lines, Allahabad-211001. Allahabad Bank, Zonal Office Phone – 0532-2622883 FAX - 2420325 22 -P, Purushottam Das Tandon e-mail – [email protected] Marg, Civil Lines, Allahabad-211001. 2 Sri Vineet Bajpai Allahabad Bank, Zonal Office BAHRAICH Phone – 0532-2622883 FAX – Assistant General 114, Raipur Raja, Civil Lines, ZONE 2420325 Manager Bahraich – 271801Phone – 05252-232539 Email: FAX - 236151e-mail – [email protected] [email protected] 3 Sri Vijay Kumar Allahabad Bank, Zonal Office GONDA Assistant General Near Roadways Bus Stand, Bahraich Road ZONE Manager Gonda (UP) Phone – 05262-232761 FAX - 232762 e-mail – [email protected] 4 Sri Ajit Kumar Jha Allahabad Bank, Zonal Office GORAKHPUR Deputy General Mohaddipur, Kashya Road, Post – Kuraghat, ZONE Manager Gorakhpur- 2731008 Phone – 0551-2202564 FAX – 2200008 e-mail – [email protected] 5 Sri Rananjay Singh Allahabad Bank, Zonal Office HAMIRPUR Assistant General 10/379 Ramedi Tarauns, Hamirpur-210301 ZONE Manager Phone – 05282223205 FAX - 222282 e-mail – [email protected] 6 Sri Vinod kumar Dixit Allahabad Bank, Zonal Office, MIRZAPUR Assistant General Juley Garden, Jangi Road, Mirzapur-231001 ZONE Manager Phone – 05442-245209 FAX - 245984 e-mail – [email protected] 7 Sri Shashank Jain Allahabad Bank, Zonal Office, VARANASI Deputy General Takshal Theatre Building Nadesar, ZONE Manager Varanasi-221 002. -

ZONE RANGE DISTRICT MAIL with PHONE NUMBERS.Xlsx

Name of District/Range POST QMAIL NIC POLICE OFFICE CUG OTHERS / FAX 2nd office no 1 1 Agra Zone ADG/IG [email protected] [email protected] 0562-2265736 9454400178 0562-2260088 9454405165 2 1 Agra Range IG/DIG [email protected] [email protected] 0562-2463343 9454400197 0562-2262000 9454402767 3 AGRA SSP [email protected] [email protected] 0562-2250106 9454400246 0562-2227256 4 FIROZABAD SP [email protected] [email protected] 05612-285110 9454400269 05612-285044 5 MAINPURI SP [email protected] [email protected] 05672-234442 9454400295 05672-234402 6 MATHURA SSP [email protected] [email protected] 0565-2505172 9454400298 0565-2409620 7 2 Aligarh Range DIG [email protected] [email protected] 0571-2400404 9454400392 9454404726 9454404726 8 ALIGARH SSP [email protected] [email protected] 0571-2401150 9454400247 0571-2703111 0571-2401454 9 ETAH SSP [email protected] [email protected] 05742-233319 9454400265 05742-233303 10 HATHRAS (MAHAMAYA NAGAR) SP [email protected] [email protected] 05722-232100 9454400278 05722-276100 11 KASGANJ (KASHIRAM NAGAR) SP [email protected] [email protected] 05744-247486 9454400393 05744-247487 12 2 Allahabad Zone ADG/IG [email protected] [email protected] 0532-2424630 9454400139 0532-2424630 9454405170 13 3 Allahabad Range IG/DIG [email protected] [email protected] 0532-2260527 9454400195 0532-2260527 9454402583 14 ALLAHABAD SSP [email protected] [email protected] 0532-2641902 9454400248 0532-2250600 15 FATEHPUR SP [email protected] [email protected]