Forges and Furnaces Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elizabeth Furnace Plantation Herbert H

Elizabeth Furnace Plantation Herbert H. Beck Elizabeth Furnace Plantation, one of the historic and picturesque features of Pennsylvania, began with John Jacob Huber of Germany. In 1746 Huber acquired 400 acres of lands, with allowance of 18 acres for roads, then in Warwick Township, Lancaster County; and about the same year, he built a one-and-a-half story dwelling there. This building, which was restored about 1925 by Miss Fannie Coleman, is in the approximate center of the original quadrangle of buildings at Elizabeth. About 1750 Huber erected a blast furnace 125 yards southeast of his house, making use of the impounded stream, Furnace (or Broadwater) Run, to drive its blast. His ore and limestone came from Cornwall mines, nine miles away, his charcoal from woodlands adjoining the furnace. Aside of the furnace there was a casting house in which five plate stoves were made. Today there is a plate of such a stove at Ephrata Cloister marked: "Jacob Huber erste deutsche mann 1755." This is part of an in- scription, traditionally on Huber's furnace, which read: "Johan Jacob Hu- ber der erste deutsche Mann der das Eisenwerk volfuhren kann." (John Jacob Huber the first German man who can manage ironwork.) Like his son-in-law, Henry William Stiegel, Huber was a great advertizer. Heinrich Wilhelm Stiegel Heinrich Wilhelm Stiegel, born in Cologne in 1729, came to America in 1750 and soon found employment with Huber. In 1752 he married Huber's daughter, Elizabeth. Stiegel was a man of great enterprise, pomp and display. His career was meteoric, rising like a rocket to great heights only to fall within eighteen years. -

CHAPTER 3 NATURAL RESOURCES Percent, Respectively

Dauphin County Comprehensive Plan: Basic Studies & Trends CHAPTER 3 NATURAL RESOURCES percent, respectively. The mean annual sunshine To assist in providing orderly, intelligent, Average Annual Temperature 50° F per year for the County is about 2,500 hours. and efficient growth for Dauphin County, it is Mean Freeze-free Period 175 days Summer Mean Temperature 76° F Although the climate will not have a major essential that features of the natural environment Winter Mean Temperature 32° F effect on land uses, it should be considered in the be delineated, and that this information be layout of buildings for purposes of energy integrated with all other planning tools and Winds are important hydrologic factors consumption. Tree lines and high ground should be procedures. because of their evaporative effects and their on the northwest side of buildings to take association with major storm systems. The advantage of the microclimates of a tract of land. To that end, this chapter provides a prevailing wind directions in the area are from the By breaking the velocity of the northwest winds, compilation of available environmental data as an northwest in winter and from the west in spring. energy conservation can be realized by reducing the aid to planning in the County. The average wind speed is 10 mph, with an temperature slightly. To take advantage of the sun extreme wind speed of 68 mph from the west- for passive or active solar systems, buildings should CLIMATE northwest reported in the Lower Susquehanna area have south facing walls. during severe storm activity in March of 1955. -

2018 Pennsylvania Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws PERMITS, MULTI-YEAR LICENSES, BUTTONS

2018PENNSYLVANIA FISHING SUMMARY Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws 2018 Fishing License BUTTON WHAT’s NeW FOR 2018 l Addition to Panfish Enhancement Waters–page 15 l Changes to Misc. Regulations–page 16 l Changes to Stocked Trout Waters–pages 22-29 www.PaBestFishing.com Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 18 Southeastern Regular Opening Day 2 TROUT OPENERS Counties March 31 AND April 14 for Trout Statewide www.GoneFishingPa.com Use the following contacts for answers to your questions or better yet, go onlinePFBC to the LOCATION PFBC S/TABLE OF CONTENTS website (www.fishandboat.com) for a wealth of information about fishing and boating. THANK YOU FOR MORE INFORMATION: for the purchase STATE HEADQUARTERS CENTRE REGION OFFICE FISHING LICENSES: 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 of your fishing P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Phone: (814) 359-5110 BOAT REGISTRATION/TITLING: license! Phone: (866) 262-8734 Phone: (717) 705-7800 Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. The mission of the Pennsylvania Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday PUBLICATIONS: Fish and Boat Commission is to Monday through Friday BOATING SAFETY Phone: (717) 705-7835 protect, conserve, and enhance the PFBC WEBSITE: Commonwealth’s aquatic resources EDUCATION COURSES FOLLOW US: www.fishandboat.com Phone: (888) 723-4741 and provide fishing and boating www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia opportunities. REGION OFFICES: LAW ENFORCEMENT/EDUCATION Contents Contact Law Enforcement for information about regulations and fishing and boating opportunities. Contact Education for information about fishing and boating programs and boating safety education. -

Wild Trout Streams Proposed Additions and Revisions January 2019

Notice Classification of Wild Trout Streams Proposed Additions and Revisions January 2019 Under 58 Pa. Code §57.11 (relating to listing of wild trout streams), it is the policy of the Fish and Boat Commission (Commission) to accurately identify and classify stream sections supporting naturally reproducing populations of trout as wild trout streams. The Commission’s Fisheries Management Division maintains the list of wild trout streams. The Executive Director, with the approval of the Commission, will from time-to-time publish the list of wild trout streams in the Pennsylvania Bulletin. The listing of a stream section as a wild trout stream is a biological designation that does not determine how it is managed. The Commission relies upon many factors in determining the appropriate management of streams. At the next Commission meeting on January 14 and 15, 2019, the Commission will consider changes to its list of wild trout streams. Specifically, the Commission will consider the addition of the following streams or portions of streams to the list: County of Mouth Stream Name Section Limits Tributary To Mouth Lat/Lon UNT to Chest 40.594383 Cambria Headwaters to Mouth Chest Creek Creek (RM 30.83) 78.650396 Hubbard Hollow 41.481914 Cameron Headwaters to Mouth West Creek Run 78.375513 40.945831 Carbon Hazle Creek Headwaters to Mouth Black Creek 75.847221 Headwaters to SR 41.137289 Clearfield Slab Run Sandy Lick Creek 219 Bridge 78.789462 UNT to Chest 40.860565 Clearfield Headwaters to Mouth Chest Creek Creek (RM 1.79) 78.707129 41.132038 Clinton -

Nomination Form

UMD 1YU. 1 WLlt-UU 10 United States Department of the interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and dfstricts. See instructtons in How to Compiete the Nation81 Rsg~sterof Historic Pteces Rsg~sfrationFm (National Reg~sterButittin IOA). Compleie each Mrn by mark14 "x" In the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item doe not apply to the propeny bemg docmenled, enter "MIA" for "not appticable" For functions, archibdural classification, materials, and anas of signrficance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instmcfions. Place additional entrles and narraeve items on continuatlon sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typemter, word processor,or computer, in mmplete all items. I.Mama of Property historic name Redwell-lsabella Furnace Historic District cther nameslsite number VDHR file co. 069-5252 2. Location street S number Between SR 652 and Hawksbill Creek on north side of Luray -NIA not for publication dly or town Luray X vlcinity state Viroin~a code VA county Paqe code 139 zip code 22835 3. StatelFederal Agency Certification As the des~gnaledauthority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, 1 hereby certify that this 2 norn~nation- request for determination of eligibility meets the docurnentarion standards for registering properties in the National Register sf Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant -nationally -statewide & locally, ( Seecontinuation sheet for additional comments.) / --4,--= Signature of cefi$ng offrcialrritle Virqinia Department of Historic Resources State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property -meets -does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

Swatara Creek

SWATARA CREEK Description Swatara Creek is a large watershed covering, 571 mi2, 127.3 mi2 of which are in Dauphin County. The stream originates in Berks and Schuykill Counties, generally moving southwest through Lebanon and Dauphin Counties where it meets the Susquehanna River at Middletown Borough. Major tributaries in Dauphin County include Beaver Creek, Kellock Run, Manada Creek, and Bow Creek entering Swatara Creek from the north and Spring Creek East entering from the south. The watershed in Dauphin County is characterized by extensive suburban development with some areas of farmland and forestland. Population centers in the watershed include Hershey and surrounding area, Hummelstown Borough, and Middletown Borough. Swatara Creek before entering the Susquehanna River. Topography in the watershed is characterized by relatively low, rolling hills. The geology of the watershed is composed of two geologic formations. QUICK FACTS The formation in the northern and eastern portion of the watershed contains shale, limestone, dolomite, and sandstone. Geology in the southwestern portion Watershed Size: 571 mi2, is characterized by red sandstone, shale and 127 mi2 in conglomerate intruded by diabase. In areas of the Dauphin County watershed underlain by limestone, Karst topography dominates with many areas prone to sinkhole Land Uses: Wide variety formation. Stream Miles: 253.3 DEP Classification Impaired Stream Miles: 58.1 Swatara Creek watershed Swatara Creek and most of its major tributaries are DEP Stream Classification: classified as a Warm Water Fishery (WWF). Most of Section of Manada Creek from source to I-81 – CWF its major tributaries are also classified as WWF. Swatara Creek and all other tributaries – WWF However, Manada Creek from its source to Interstate- 81 is listed as a Cold Water Fishery (CWF). -

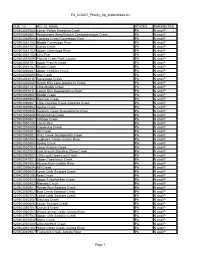

PA COAST Priority Ag Watersheds.Xls

PA_COAST_Priority_Ag_Watersheds.xls HUC_12 HU_12_NAME STATES PARAMETER 020503050505 Lower Yellow Breeches Creek PA N and P 020700040601 Headwaters West Branch Conococheague Creek PA N and P 020503060904 Cocalico Creek-Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061104 Middle Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061701 Conoy Creek PA N and P 020503061103 Upper Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061105 Lititz Run PA N and P 020503051009 Fishing Creek-York County PA N and P 020402030701 Upper French Creek PA N and P 020503061102 Muddy Creek PA N and P 020503060801 Upper Chickies Creek PA N and P 020402030608 Hay Creek PA N and P 020503051010 Conewago Creek PA N and P 020402030606 Green Hills Lake-Allegheny Creek PA N and P 020503061101 Little Muddy Creek PA N and P 020503051011 Laurel Run-Susquehanna River PA N and P 020503060902 Middle Creek PA N and P 020503060903 Hammer Creek PA N and P 020503060901 Little Cocalico Creek-Cocalico Creek PA N and P 020503050904 Spring Creek PA N and P 020503050906 Swatara Creek-Susquehanna River PA N and P 020402030605 Wyomissing Creek PA N and P 020503050801 Killinger Creek PA N and P 020503050105 Laurel Run PA N and P 020402030408 Cacoosing Creek PA N and P 020402030401 Mill Creek PA N and P 020503050802 Snitz Creek-Quittapahilla Creek PA N and P 020503040404 Aughwick Creek-Juniata River PA N and P 020402030406 Spring Creek PA N and P 020402030702 Lower French Creek PA N and P 020503020703 East Branch Standing Stone Creek PA N and P 020503040802 Little Lost Creek-Lost Creek PA N and P 020503041001 Upper Cocolamus Creek -

Scotch-Irish Presbyterian Pioneering Along the Susquehanna River*

SCOTCH-IRISH PRESBYTERIAN PIONEERING ALONG THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER* BY GuY S. KLETT 1 ARIED as the motives were that prompted multitudes of VS cotch-Irish to leave the North of Ireland for the Wilderness of America, there is one that appeared uppermost in the minds of many upon their arrival in Pennsylvania. The religious disabilities in Ireland and the economic and political restrictions arising there- from, fortunately did not dog their tracks when they arrived in Pennsylvania. So the prime motive was to earn a livelihood on land that they could claim as their own. Before these Ulster Scots migrated to America they had been characterized as land-hungry. In 1681 the inhabitants of the North of Ireland were described as "the Northern Presbyterians and Fanatics, able-bodied, hearty and stout men, where one may see 3 or 400 at every meetinghouse on Sundays and all the North is inhabited with these, which is the most populous place of all Ireland by far. They are very numerous and greedy after land."' Both James Logan and Richard Peters bear testimony to this insatiable hunger for land. Logan, quite sympathetic to fellow Ulsterites, was, however, greatly concerned with this large migra- tion of land-hungry people. Some he characterized as "truly hon- est" but others as "capable of the highest villainies." They rarely made any attempt to purchase land. He complained that they pushed to the Pennsylvania-Maryland boundary in Chester and Lancaster counties and settled "any where with or without leave, and on any spott that they think will turn out grain to afford them a maintenance."' It was choice territory for them because no rental or price could be put on the land that was disputed terri- *A paper read before the Annual Meeting of the Pennsvlvania Historical Association, at Selinsgrove, October 17-18, 1952. -

The Hidden Economy of Slavery: Commercial and Industrial Hiring in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware, 1728-1800

THE HIDDEN ECONOMY OF SLAVERY: COMMERCIAL AND INDUSTRIAL HIRING IN PENNSYLVANIA, NEW JERSEY AND DELAWARE, 1728-1800 Michael V. Kennedy University ofMichigan-Flint ABSTRACT Industrial and commercial businesses in the Mid-Atlantic region depended on a controllable workforce of slaves during the eighteenth century; A sig nificant percentage of these slaves were hired from private citizens who regu larly profited from the exchange. Because of the almost continuous move ment of slaves across township, county and colony borders due to hiring-out practices, slaves in tax and census lists were routinely under-reported. The use of business accounts listing hires and labor done by slaves reveals the extent and importance ofslave hiring and additional numbers ofslaves owned in the region that were otherwise invisible. In 1767, Pennsylvania’s Charming Forge hired one of blacksmith John Herr’s slaves to work as a hammerman at the company finery for the term of one year. Since the slave was unnamed, it is unclear if this was the same slave Herr hired out nearly every year until 1775. It is only known that the forge had the use of a slave hired from Herr annu ally;’ In 1773, Tom May, manager ofPine Forge, hired James Whitehead’s slave Wetheridge as a woodcutter on a monthly basis. Wetheridge worked at least three months, and White- head was paid at the end of the year for his slave’s services.2 Union Forge hired farmer William Wood’s slave Bob to work in the chafery and to cut wood on an annual basis between 1785 and 1789. -

Natural Resources Profile

BBaacckkggrroouunndd SStttuuddyy ##66 Natural Resources Profile The Natural Resources Profile is designed to identify and analyze the vast assortment of natural resources that are found within or have an influence on Lebanon County. These resources and features include the physical geography; topography; soils; geologic formations and physiographic provinces; water resources; wellhead protection; woodlands; and wildlife and their value to economic pursuits, such as agriculture and forestry, and to the county’s overall environmental quality. The purpose of the profile is to help local, regional, and state government officials and decision-makers, developers, and citizens make more informed planning decisions. Sensitive environmental resources, threats to resource existence and function, development impacts, and types of protection techniques are of specific interest, as they aid in the identification of natural resources in need of remediation, features that impose development constraints, areas to be preserved, and places that are well-suited for development. Physical Geography Lebanon County is located in the Lebanon Valley between South Mountain, which rises to an elevation of 800 to 1,000 feet, and the Blue Mountain Chain to the north, which reaches peaks of 1,300 to 1,500 feet. The Lebanon Valley is divided into several smaller valleys by lines of hills parallel to the ensconcing mountains. The valley lies on the northern edge of the Southeast Piedmont Climatological Division which also includes Dauphin, Berks, Lancaster, Chester, Bucks, Montgomery, Delaware, and Philadelphia Counties and is more or less a transition zone from the piedmont region to the East Central Mountain and Middle Susquehanna Climatic Divisions.1 Climate The climate of Lebanon County is best described as humid continental. -

The Grubbs the Colemans and the Iron Industry in Elizabethtown .Pdf

FYS 100 HD Landmarks & Legends: Learning Local History Ryan Runkle Professor Benowitz Jonathan Freaney Jacob Beranek 28 November 2017 The Grubbs, The Colemans, and The Iron Industry in Pennsylvania The Grubb family were iron-masters in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, for over 165 years. Back in 1677, John Grubb came from Cornwall, U.K., settled in Delaware, and established a tannery. He had nine children, the last of whom, Peter Grubb, was a mason. Peter first learned stonemasonry as a trade, building a water, corn, and boulting mill in Bradford, Pennsylvania in 1729. Around a decade later, in 1737, he discovered the Cornwall ore hill – also known as the Cornwall Iron Mines, one of the richest iron ore deposits east of Lake Superior, in Lebanon County, about 21 miles north of Lancaster. There, Peter built the Cornwall Iron Forge and two forges nearby on Hammer Creek, called the Upper and Lower Hopewell Forges. Most of the property was eventually sold over to Robert Coleman, a former clerk of the Grubbs’, who maintained the forges until his own forge, Speedwell Forge, was shut down. The forges produced at least 250 tons of materials in the year 1833. Peter had two sons: Peter Grubb Jr. and Curtis Grubb, both of whom inherited the ironworks after Peter’s death in 1754. After the lease had expired, the two took over the business and expanded it. Curtis Grubb, the older of the siblings, received the larger portion of the inheritance. However, due to issues, such as remarriage, all of Curtis’ portions were eventually sold over to Robert Coleman by his children.