Ÿþm I C R O S O F T W O R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

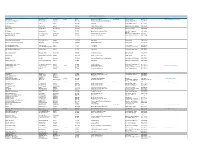

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

Pontesbury Village Profile - 2018

Pontesbury Village Profile - 2018 Pontesbury is a large village and civil parish which lies approximately 8 miles south west of the county town of Shrewsbury. The parish also includes the hamlets of Pontesford, Plealey, Asterley, Cruckton , Cruckmeole, Arscott, Lea Cross, Habberley and Malehurst. The village is located alongside the A488 road which runs from Shrewsbury to Bishop’s Castle. The village is a mile away from neighboring Minsterley and sits at the north edge of the Shropshire Hills AONB. The nearest station is Shrewsbury. The village has a number of thriving small shops and businesses and has a doctors, dentist and a police station and pubs. The village is surrounded by beautiful countryside and farmland. The Earls Hill nature reserve, Coppice Wood and Pontesford Hill are popular landmarks and walks in the area. The Reabrook runs close by to Pontesbury. Key Facts and Geography Area: 80.75 Hectares Population Density: 23.2 persons per hectare There is a local primary school Pontesbury Primary School Total Population 1,873 and the village falls into the catchment for Mary Webb Households: 817 School. And Science College. Please visit Shropshire Council Dwellings: 840 website for more details of schools in the and catchment areas. Communal Establishment 1 Source: 2011 Census View a map of schools in Shropshire Phone: 0345 678 9000, Email: [email protected] Information, Intelligence & Insight Team Contents Page Location Maps 3 Demographics 4 Economy 11 Health 14 Housing 17 Additional Information This Profile uses the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Built up Area (BUA) geography which is available for the 2011 Census results. -

Pontesbury Parish Council

Pontesbury Parish Council NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT THE NEXT MEETING OF PONTESBURY PARISH COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE WILL TAKE PLACE ON 3RD APRIL 2017 AT PONTESBURY PUBLIC HALL AT 6.30pm AGENDA 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CODE OF CONDUCT 3. MINUTES OF COUNCIL - To approve the Minutes of the meeting held on 6th March 2017. 4. PUBLIC QUESTIONS AND COMMENTS – (Fifteen minutes will be allowed) 5. REQUEST FOR CONFIRMATION OF LOCAL CONNECTION RELATING TO THE SHROPSHIRE COUNCIL AFFORDABLE HOUSING SCHEME - Tricia Harrison-Rogers, 6 Ensdon, Montford Bridge, Shrewsbury, SY41EN (Parents live at Woodfield, Cruckton) 6. PLANNING APPLICATIONS 6.1. Planning Decisions for Pontesbury Parish Council Area To receive details of planning decisions made between 25th February 2017 to 24th March 2017 6.2. Pre-application consultation request To consider pre-application request for informal comments on proposals to rebuild Conway, Plealey. 6.3. Planning Applications for Pontesbury Parish Council Area To consider submitting comments and/or objections on the following applications received for planning consent: a) 17/00947/FUL - Erection of two storey extension with first floor balcony (modification to previous application) - Hill View Arscott Shrewsbury Shropshire SY5 0XP b) 17/01027/VAR106 - Variation of Section 106 for planning application number 13/00798/OUT to remove the requirement to contribute towards affordable housing - Cherry Cottage Lower Road Pontesbury Shrewsbury Shropshire SY5 0YH a) 16/04747/FUL -

Placement Contact Lists from 2019

Placement Contact Lists FROM 2019 Placement Placement Address1 Placement Address 2 Town Postcode Occupational Area Type of Business Contact Telephone No. Email Address 3D Hair Studio 50 West Street St Georges Telford TF2 9 Hairdressers assistant Hairdressers Deborah Heaney 07813 712610 [email protected] 7 Sence Event Management The Town House Oswestry SY11 1AQ Business Admin/Professional Management Charlotte Gwynne (Event 01691 670027 Manager) 7 Valley Transport Unit 29 Shifnal TF11 8SD Transport Glenys Hillman - Owner 01952 461991 A H Griffiths 11 Bull Ring Ludlow SY8 1AD Retail / Customer Service Matthew Sylvester - Manager 01584 872141 A Ryan & Son 60 High Street Much Wenlock TF13 6AE Retail / Customer Service Sue Ryan - Manager 01952 727409 A T Browns Hortonwood 50 Telford TF1 7GZ Motor Vehicle & Associated Trade Dave Price - Operations 01952 605331 Manager A Walters Electrician Contractor 62 Longden Road Shrewsbury SY3 7HG Plant and Tool Hire/ Contractor Mike Davis- Operations Director 01743 247850 Aardvark Books Ltd The Bookery Bucknell SY7 0DH Retail / Customer Service Sarah Swinson (Director) 01547 530744 Abacus Day Nursery (Newport) 38 St Mary's Street Newport TF10 7AB Educational Leanne Nolan 01952 813652 Abbey Veterinary Centre (Shawbury) High Ridge Shrewsbury SY4 4NW Working With Animals Tracie Howells 01939 250655 ABC Day Nursery (Hadley) Crescent Road Telford TF1 5JU Educational Emma Burrows 01952 387190 ABC Day Nursery (Hoo Farm) Hoo Farm Animal kingdom, Telford TF6 6DJ Educational Lucy Holbrook - Manager 01952 -

Shropshire Youth Association

Westbury and Yockleton Newsletter Local News: July 2021 Stay connected, stay informed Keeping our communities informed. It's packed with Monthly Current News: Local Events; Announcements; POLICE crime figures; Planning Applications Local Resources and what's going on Yockleton Westbury Westbury and Yockleton Newsletter Issue 228 - July 2021 News items for the Newsletter should go to the Editor, Rita Waters, Dingley Dell, Westbury, Shrewsbury SY5 9QX Tel: 01743 884434, email: [email protected] Business adverts and any new businesses wishing to place adverts should also contact the Editor preferably by email. Items for inclusion in the Newsletter must reach me by : for the August 2021 edition : 9am Monday, 26 July 2021 and for the September 2021 edition : 9am Monday, 23 August 2021. Westbury Village Hall Westbury Youth Club :The “physical” Youth Club Westbury Parish Council : It is hoped that the next has closed; however - conscious that the Covid-19 virus two meetings will be held in Westbury Village Hall on situation is putting a huge strain on everyone, Lee and Thursday, 2 September 2021 and on Thursday, Hayley are keeping in touch with the young people and 4 November 2021, both meetings commencing at will run a “virtual” Youth Club, which is being 7.30pm. These dates may be subject to change due to advertised through their Facebook page. For further the Covid-19 virus situation. Should any member of information, call Richard Parkes, Chief Executive the public wish to join these meetings, it is requested Officer, Shropshire Youth Association. Tel: 01743 that they first contact : Mrs Sarah Smith, Parish Clerk 730005 or 07710095802 (Mobile). -

West Midlands Aggregate Working Party

URBAN VISION PARTNERSHIP LTD West Midlands Aggregate Working Party Annual Monitoring Report 2015, incorporating data from January – December 2015 For further information on this document and the West Midlands Aggregates Working Party, please contact: Chairman Adrian Cooper Team Leader, Environment & Economic Policy Shropshire Council The Shirehall Abbey Foregate Shrewsbury SY2 6ND Tel: 01743 252568 [email protected] Secretary Mike Halsall Senior Planning Consultant: Minerals & Waste Planning Unit Urban Vision Partnership Ltd Emerson House Albert Street Salford M30 0TE Tel: 0161 779 6096 [email protected] (Previously Ian Thomas, National Stone Centre and then Hannah Sheldon Jones, Urban Vision) The statistics and statements contained in this report are based on information from a large number of third party sources and are compiled to an appropriate level of accuracy and verification. Readers should use corroborative data before making major decisions based on this information. Published by Urban Vision Partnership Ltd on behalf of the West Midlands Aggregates Working Party. This publication is also available electronically free of charge on www.communities.gov.uk and www.urbanvision.org.uk. 2 West Midlands AWP Annual Monitoring Report 2015 Executive Summary The West Midlands Aggregate Working Party (AWP) is one of nine similar working parties throughout England and Wales established in the 1970's. The membership of the West Midlands AWP is detailed in Appendix 1. This Annual Monitoring (AM) report provides sales and reserve data for the calendar year 2015. The report provides data for each of the sub-regions in the West Midlands: • Herefordshire • Worcestershire • Shropshire • Staffordshire • Warwickshire • West Midlands Conurbation . -

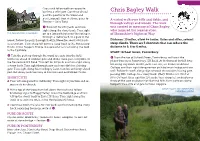

Chris Bagley Walk Past the Pool in to the Wood and Past Lingcroft Pool Via Three Gates to a Varied Walk Over Hills and Fields, and Plealey – Oaks Road

Cross and follow path on opposite bank to a stile/gate. Continue ahead Chris Bagley Walk past the pool in to the wood and past Lingcroft Pool via three gates to A varied walk over hills and fields, and Plealey – Oaks Road. through valleys and woods. The walk 7 Turn left for 250 yards and turn was created in memory of Chris Bagley right along the stony track. Turn right who inspired the regeneration THE OLD RECTORY, HABBERLEY on to a footpath between the cottages, of Shropshire’s Rights of Way. through a stable yard, to a gate in the wood. Follow the path through Radlith Wood for about 400 yards Distance: 10 miles, allow 4+ hours. Gates and stiles, several to a junction. Turn sharp left down a steep track to the Pontesford steep climbs. There are 3 shortcuts that can reduce the Brook. Cross Bagger’s Bridge to a gate and turn left along the field distance to 9, 8 or 6 miles. to the Lyd Hole. START: School Green, Pontesbury. 8 Take the path up through the wood to a gate into the field. 1 From the top of School Green, Pontesbury, walk past the Continue ahead to wooden gate and follow track, past two pools, to phone box on to Pontesbury Hill Road. At the brow of the hill bear the Pontesford Hill Road. Turn left for 80 yards and turn right along left along Top Road. In 250 yards turn left just before Gladstone a stony track. Turn right through gate and cross field to a kissing Cottage and then right along narrow path between hedge and low gate. -

Shropshire Cycleway Shropshire

Leaflet edition: SCW5-1a/Feb2015 • Designed by MA Creative Limited www.macreative.co.uk Limited Creative MA by Designed • SCW5-1a/Feb2015 edition: Leaflet This leaflet © Shropshire Council 2015. Part funded by the Department for Transport for Department the by funded Part 2015. Council Shropshire © leaflet This www.bicyclesmart.co.uk 01743 537124 01743 07528 785844 07528 Newport SY3 8JY SY3 Bicycle Smart Bicycle 20 Frankwell, Shrewsbury Shrewsbury Frankwell, 20 (MTB specialist) (MTB Trailhead The www.pjcyclerepairs.co.uk www.pjcyclerepairs.co.uk 07722 530531 07722 www.hawkcycles.co.uk Condover 01743 344554 01743 Repairs Cycle PJ SY1 2BB SY1 Shrewsbury www.bicyclerepairservices.co.uk www.bicyclerepairservices.co.uk 15 Castle Street Castle 15 07539 268741 07539 Hawk Cycles Hawk Broseley Bicycle Repair Services Services Repair Bicycle www.urbanbikesuk.co.uk 01686 625180 01686 www.cycletechshrewsbury.co.uk www.cycletechshrewsbury.co.uk 07828 638132 638132 07828 07712 183148 07712 Shrewsbury SY1 1HX SY1 Shrewsbury Stapleton Shrewsbury Market Hall Market Shrewsbury Cycle Tech Shrewsbury Shrewsbury Tech Cycle Unit 9-10, 9-10, Unit Urban Bikes UK Bikes Urban www.gocycling-shropshire.com www.gocycling-shropshire.com 07950 397335 07950 www.shrewsburycycles.co.uk Go Cycling Go 01743 232061 01743 SY1 4BE SY1 Mobile bike mechanics bike Mobile Shrewsbury Road, Ditherington 43 Cyclelife Shrewsbury Cyclelife www.halfords.com www.stanscycles.co.uk www.stanscycles.co.uk to Shropshire. Shropshire. to 01743 270277 01743 01743 343775 01743 attractive and -

Flash Flood History Severn and Welsh Borders

Flash flood history Severn and Welsh Borders Hydrometric Rivers Tributaries Towns and Cities area 54 Severn Date and Rainfall Description sources 13-15 Jul <Worcs>: Thunderstorm with heavy rain and hail caused flooding in Worcestershire. 1640 Townshend’s Diary Jones et al 1984 6 Jun 1697 This followed even more <Westhide> (Hereford): In a hailstorm the hailstones were more than 70 mm across. There was no reference to Webb and devastating storms in flooding. Cheshire and Herts Elsom 2016 5 Jul 1726 <Ledbury>, <Herefordshire>: There happened such a sudden shower of rain accompanied by thunder and Ipswich Jour 9 lightning that in the space of half an hour the town was almost drowned, several of the houses being six foot Jul deep in water so that had they not opened the doors and windows to let it out they would have been carried Stanley’s away with the torrent. Several farmers had their litter carried away and many persons their goods and in rooms Newsletter Jul 14 thereof some had fish brought into their lower rooms that was driven out of adjacent ponds. 19 Jun 1728 <Gloucester>: We hear from <Arlington> in the parish of <Bibury> that there happened such a prodigious storm Caledonian of rain that the like has not been seen for more than thirty years which in the space of half an hour caused a Mercury 4 Jul dreadful flood that it carried away more than 50 cartloads of stones some of which were judged to be more than ‘300 Weight’ and fixed in the road which the violence of the flood tore up and drove down the highway and in our common field the mould of several acres was carried off. -

Proposed Development Land South of Plealey Lane, Longden

Committee and date Central Planning Committee 21 May 2015 Development Management Report Responsible Officer: Tim Rogers email: [email protected] Tel: 01743 258773 Fax: 01743 252619 Summary of Application Application Number: 15/00724/OUT Parish: Longden Proposal : Outline application for residential development (to include access) (revised scheme) Site Address : Proposed Development Land South Of Plealey Lane Longden Shropshire Applicant : Mr & Mrs D Jones Case Officer : Andrew Gittins email : [email protected] Grid Ref: 344020 - 306547 © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Shropshire Council 100049049. 2011 For reference purposes only. No further copies may be made. Contact: Tim Rogers (01743) 258773 Proposed Development Land Central Planning Committee – 21 May 2015 South of Plealey Lane Longden Recommendation: Grant permission subject to the conditions set out in Appendix 1, and to prior completion of a legal agreement to secure the provision of affordable housing; provision of new 3m wide hard surfaced footway link to existing public footpath through the school grounds, with the existing footpath resurfaced in macadam to a width of 1.8m; and the transfer of 3 metre wide section of land to the south of the existing playing field to Shropshire Council. REPORT 1.0 THE PROPOSAL 1.1 This proposal is an outline application for residential development. Approval for the proposed access is sought, with all other matters (appearance, landscaping, layout and scale) reserved for later approval. Access to the development would be gained via Plealey Lane, the adjacent public highway to the north of the application site. 1.2 Condition 4 has been recommended to ensure that the Reserved Matters is for no more than 20 dwellings. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Central Planning Committee, 31/08

Shropshire Council Legal and Democratic Services Shirehall Abbey Foregate Shrewsbury SY2 6ND Date: Tuesday, 22 August 2017 Committee: Central Planning Committee Date: Thursday, 31 August 2017 Time: 2.00 pm Venue: Shrewsbury Room, Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6ND You are requested to attend the above meeting. The Agenda is attached Claire Porter Head of Legal and Democratic Services (Monitoring Officer) Members of the Committee Substitute Members of the Committee Dean Carroll Peter Adams Ted Clarke (Chairman) Roger Evans Nat Green (Vice Chairman) Hannah Fraser Nick Hignett Ioan Jones Pamela Moseley Jane MacKenzie Tony Parsons Alan Mosley Alexander Phillips Harry Taylor Ed Potter Dan Morris Kevin Pardy Lezley Picton Keith Roberts Claire Wild David Vasmer Your Committee Officer is: Shelley Davies Committee Officer Tel: 01743 257718 Email: [email protected] AGENDA 1 Apologies for absence To receive apologies for absence. 2 Minutes (Pages 1 - 6) To confirm the Minutes of the meeting of the Central Planning Committee held on 27th July 2017. Contact Shelley Davies on 01743 257718. 3 Public Question Time To receive any public questions or petitions from the public, notice of which has been given in accordance with Procedure Rule 14. The deadline for this meeting is 4 p.m. on Friday 25th August 2017. 4 Disclosable Pecuniary Interests Members are reminded that they must not participate in the discussion or voting on any matter in which they have a Disclosable Pecuniary Interest and should leave the room prior to the commencement of the debate. 5 Shrewsbury College Of Arts And Technology, Radbrook Road, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY3 9BL (17/00823/COU) (Pages 7 - 28) Change of use of land to form domestic curtilage land and formal public open space including the construction of a footpath. -

Minutes of Pontesbury Parish Council Meeting Held on 13Th May 2019 1

PONTESBURY PARISH COUNCIL Annual Meeting of Council Held at Mary Webb School & Science College, Pontesbury At 7.30pm on Monday 13th May 2019 PRESENT Cllr D Fletcher (Chairman), Cllr J Pritchard (Vice-Chairman), Cllr R Evans, Cllr N Hignett, Cllr A Hodges, Cllr N Lewis, Cllr S Lockwood, Cllr R Martinali, Cllr B Morris, Cllr P Heywood, Cllr D Jones, Cllr P Bradbury, Cllr C Sandells IN ATTENDANCE: None CLERK: Debbie Marais Five members of the public were present. 1.19 ELECTION OF CHAIRMAN Nominations were sought for the election of Chairman to the Council for the following year. It was proposed by Cllr J Pritchard and seconded by Cllr R Martinali and it was unanimously RESOLVED that Cllr D Fletcher be elected as Chair for the year 2019/20. Cllr Fletcher took the chair. 2.19 ELECTION OF VICE CHAIRMAN Nominations were sought for the election of Vice-Chairman to the Council. It was proposed by Cllr N Lewis and seconded by Cllr N Hignett and it was unanimously RESOLVED that Cllr J Pritchard be elected as Vice-Chair for the year 2019/20. 3.19 DECLARATIONS OF ACCEPTANCE OF OFFICE Cllr D Fletcher and Cllr J Pritchard were asked to sign the Declaration of Acceptance of Office as Chair and Vice-Chair to the Parish Council. 4.19 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Cllr C Robinson and Cllr D Gregory for personal reasons 5.19 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST AND DISPENSATIONS - None 6.19 PUBLIC QUESTIONS AND COMMENTS Resident 1. Expressed concerns about the following; • Burning practices of Budget Skips in Cruckmeole.