The Synchronisms of the Hebrew Kings-A Re-Evaluation : I Edwin R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept of Kingship

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Jacob Douglas Feeley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Jacob Douglas, "Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2276. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Abstract Scholars who have discussed Josephus’ political philosophy have largely focused on his concepts of aristokratia or theokratia. In general, they have ignored his concept of kingship. Those that have commented on it tend to dismiss Josephus as anti-monarchical and ascribe this to the biblical anti- monarchical tradition. To date, Josephus’ concept of kingship has not been treated as a significant component of his political philosophy. Through a close reading of Josephus’ longest text, the Jewish Antiquities, a historical work that provides extensive accounts of kings and kingship, I show that Josephus had a fully developed theory of monarchical government that drew on biblical and Greco- Roman models of kingship. Josephus held that ideal kingship was the responsible use of the personal power of one individual to advance the interests of the governed and maintain his and his subjects’ loyalty to Yahweh. The king relied primarily on a standard array of classical virtues to preserve social order in the kingdom, protect it from external threats, maintain his subjects’ quality of life, and provide them with a model for proper moral conduct. -

1 Kings 15-16

Book of First Kings I Kings 15-16 The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly This section of 1 Kings gives a brief survey of the kings of Judah and Israel from 913 to 885 B.C. From this point through the rest of 1 Kings, a cross reference is used in introducing each new king of Judah and Israel. When each king begins his reign it is connected to the reigning king of the other kingdom. Eight of Judah’s kings were good, but most were bad kings. Four kings of Judah (Asa, Jehoshaphat, Hezekiah, and Josiah) led notable religious revivals at critical times to preserve the nation. All of Israel’s kings were bad, but some were worse than others. Two Kings of Judah (15:1-24) – One bad king and one good king 1. King Abijam (15:1-8) – He reigned over Judah 3 years (913-911 B.C.). Two bad things are said about him: A. He walked in the sins for his father – Like father, like son. B. He was not devoted to the Lord – He was not loyal to God (“his heart was not perfect”) as David had been. The same thing was said about Solomon (11:4). David was mostly faithful to God except in the matter of Uriah. He took Uriah’s wife and then he took Uriah’s life. For the most part, David did what was right in the eyes of God. Proverbs 15:3 The eyes of the LORD are in every place, beholding the evil and the good. -

Not Afraid, Not Alone We Aren’T the First Ones to Feel Afraid & Alone, and We Won’T Be the Last

Not Afraid, Not Alone We aren’t the first ones to feel afraid & alone, and we won’t be the last. The Bible is FULL of people who have struggled through tough times & unanswered questions. We need to be reminded about the central message of the Christmas story - God WIth Us. * All Scripture is from CSB (Christian Standard Bible) unless otherwise noted. The central message of the Christmas story didn’t begin with Mary and Joseph & a baby named Jesus. Hundreds of miles and 2000 years removed, God’s great plan began to unfold as God called out to Abram (later known as Abraham). Genesis 26:4 I will make your offspring as numerous as the stars of the sky, I will give your offspring all these lands, and all the nations of the earth will be blessed by your offspring, The rest of the Bible is the story of God using the family of Abraham to bless all nations...through the birth, life, death, & resurrection of Jesus. In fact, the first line of Matthew’s story begins like this… Matthew 1:1 An account of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the Son of David, the Son of Abraham: Abraham’s family was tested and tried, going through many tough times...often feeling afraid & alone. Abraham’s son, Isaac was afraid of the Philistine people who mistreated him. In the middle of it, see God’s encouragement… Genesis 26:24 (LEB) And Yahweh appeared to him that night and said, “I am the God of your father Abraham. Do not be afraid, for I am with you, and I will bless you and make your descendants numerous for the sake of my servant Abraham.” Wouldn’t it be GREAT to hear those powerful words...from the God of the universe!?! ‘Do not be afraid, for I am with you’. -

When Athaliah the Mother of Ahaziah Saw That Her Son Was Dead, She Proceeded to Destroy the Whole Royal Family

Pentecost 13C, August 14 & 15 2016 TEXT: 2 Kings 11:1-3, 12-18 THEME: GOD KEEPS HIS PROMISES 1. An Attack Against God’s Promise 2. God Raised Up a Heroine to Keep His Promise When Athaliah the mother of Ahaziah saw that her son was dead, she proceeded to destroy the whole royal family. But Jehosheba, the daughter of King Jehoram and sister of Ahaziah, took Joash son of Ahaziah and stole him away from among the royal princes, who were about to be murdered. She put him and his nurse in a bedroom to hide him from Athaliah; so he was not killed. He remained hidden with his nurse at the temple of the LORD for six years while Athaliah ruled the land. … Jehoiada brought out the king's son and put the crown on him; he presented him with a copy of the covenant and proclaimed him king. They anointed him, and the people clapped their hands and shouted, "Long live the king!" When Athaliah heard the noise made by the guards and the people, she went to the people at the temple of the LORD. She looked and there was the king, standing by the pillar, as the custom was. The officers and the trumpeters were beside the king, and all the people of the land were rejoicing and blowing trumpets. Then Athaliah tore her robes and called out, "Treason! Treason!" Jehoiada the priest ordered the commanders of units of a hundred, who were in charge of the troops: "Bring her out between the ranks and put to the sword anyone who follows her." For the priest had said, "She must not be put to death in the temple of the LORD." So they seized her as she reached the place where the horses enter the palace grounds, and there she was put to death. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

THE GOOD KINGS of JUDAH Learning to Avert Moral Failure from Eight Good Men Who Didn’T

THE GOOD KINGS OF JUDAH learning to avert moral failure from eight good men who didn’t . give me an undivided heart . Psalm 86:11 Answer Guide ©2013 Stan Key. Reproduction of all or any substantial part of these materials is prohibited except for personal, individual use. No part of these materials may be distributed or copied for any other purpose without written permission. Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version® (ESV®), copyright ©2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. For information about these or other additional study materials, contact: PO Box 7 Wilmore, KY 43090 859-858-4222 800‒530‒5673 [email protected] www.francisasburysociety.com To follow Stan on his blog, visit: http://pastorkeynotes.wordpress.com. Downloadable PDFs of both student and answer guides for this study are available at www.francisasburysociety.com/stan-key. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO THE GOOD KINGS OF JUDAH .......................1 SOLOMON ................................................................................3 ASA .........................................................................................5 JEHOSHAPHAT .........................................................................7 JOASH .....................................................................................10 AMAZIAH .................................................................................12 UZZIAH....................................................................................15 -

RE111 Page 1 Day Topic Prep Reading Questions August 28 30

RE111 Day Topic Prep reading Questions August 28 What is a study bible? (Compare commentaries on Ex 20:1-18 – JSB, HCSB, WBC) 30 Academic Study of Bible WWTB 15-32 31 Academic Study II Carr, 1-14 September 3 The Bible’s setting. Carr, chapter 1 Complete the map (handout) by looking at the maps in your study Bible. We will have a map quiz on Friday. 4 Pre-monarchial Israel Carr, chapter 2 Josh 11, Jdg 1; OLR: Mernepthah Stele How do the two biblical passages present different accounts of Inscription Israel’s settlement in the Promised Land? What similarities can you find with the Mernepthah stele? 6 Exod 1-3, 5-10, 12:29-42, 14-15 What parts of this narrative demonstrate resistance to domination? Why would this ideology be attractive to Canaanite refugees setting in the mountains? 7 Map Quiz Gen 25, 27-35; Discussion: Art – Substitute “George Washington” for “Jacob” in these stories. Jacob wrestling with the Angel? Why are these stories strange to recount about the founder of the (guest lecturer?) nation? 10 (Last day to Add/Drop Jdg 4-5; OLR: How to read an academic In preparation for reading Smith, read the two short OLR articles Classes) article; Rosenberg, How to Read an about how to read an academic essay. academic article 11 OLR: Smith, 19-59. Don’t panic at the length of this reading – almost all of Smith’s pages are ½ full of footnotes, which you can skip! How does Smith characterize pre-monarchial Israelite religion? What is distinctive about it? 13 Transition to Monarchy WWTB, 33-49; Carr, chapter 3 1 Sam 8-17 Be sure you can identify: David, Solomon, Samuel, Rehoboam, and Jeroboam. -

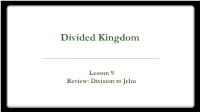

Divided Kingdom

Divided Kingdom Lesson 9 Review: Division to Jehu Divided Kingdom: Kings of Israel Jeroboam – 22y Jehoahaz – 17y Nadab - 2y Joash (Jehoash) – 16y Baasha – 24y Jeroboam II – 41y Elah – 2y Zechariah – 6m Zimri – 1w Shallum – 1m Omri – 12y Menahem – 10y Ahab – 22y Pekahiah – 2y Ahaziah – 2y Pekah – 20y Jehoram (Joram) – 12y Hoshea – 9y – 28y Divided Kingdom: Kings of Israel Jeroboam – 22y Jehoahaz – 17y Nadab - 2y Joash (Jehoash) – 16y Baasha – 24y Jeroboam II – 41y Elah – 2y Zechariah – 6m Zimri – 1w Shallum – 1m Omri – 12y Menahem – 10y Ahab – 22y Pekahiah – 2y Ahaziah – 2y Pekah – 20y Jehoram (Joram) – 12y Hoshea – 9y – 28y Divided Kingdom: Kings of Israel Jeroboam – 22y Jehoahaz – 17y Nadab - 2y Joash (Jehoash) – 16y Baasha – 24y Jeroboam II – 41y Elah – 2y Zechariah – 6m Zimri – 1w Shallum – 1m Omri – 12y Menahem – 10y Ahab – 22y Pekahiah – 2y Ahaziah – 2y Pekah – 20y Jehoram (Joram) – 12y Hoshea – 9y – 28y Divided Kingdom: Kings of Israel Jeroboam – 22y Jehoahaz – 17y Nadab - 2y Joash (Jehoash) – 16y Baasha – 24y Jeroboam II – 41y Elah – 2y Zechariah – 6m Zimri – 1w Shallum – 1m Omri – 12y Menahem – 10y Ahab – 22y Pekahiah – 2y Ahaziah – 2y Pekah – 20y Jehoram (Joram) – 12y Hoshea – 9y – 28y Divided Kingdom: Kings of Israel Jeroboam – 22y Jehoahaz – 17y Nadab - 2y Joash (Jehoash) – 16y Baasha – 24y Jeroboam II – 41y Elah – 2y Zechariah – 6m Zimri – 1w Shallum – 1m Omri – 12y Menahem – 10y Ahab – 22y Pekahiah – 2y Ahaziah – 2y Pekah – 20y Jehoram -

The Authority of Scripture: the Puzzle of the Genealogies of Jesus Mako A

The Authority of Scripture: The Puzzle of the Genealogies of Jesus Mako A. Nagasawa, June 2005 Four Main Differences in the Genealogies Provided by Matthew and Luke 1. Is Jesus descended through the line of Solomon (Mt) or the line of Nathan (Lk)? Or both? 2. Are there 27 people from David to Jesus (Mt) or 42 (Lk)? 3. Who was Joseph’s father? Jacob (Mt) or Heli (Lk)? 4. What is the lineage of Shealtiel and Zerubbabel? a. Are they the same father-son pair in Mt as in Lk? (Apparently popular father-son names were repeated across families – as with Jacob and Joseph in Matthew’s genealogy) If not, then no problem. I will, for purposes of this discussion, assume that they are not the same father-son pair. b. If so, then there is another problem: i. Who was Shealtiel’s father? Jeconiah (Mt) or Neri (Lk)? ii. Who was Zerubbabel’s son? Abihud (Mt) or Rhesa (Lk)? And where are these two in the list of 1 Chronicles 3:19-20 ( 19b the sons of Zerubbabel were Meshullam and Hananiah, and Shelomith was their sister; 20 and Hashubah, Ohel, Berechiah, Hasadiah and Jushab-hesed, five)? Cultural Factors 1. Simple remarriage. It is likely that in most marriages, men were older and women were younger (e.g. Joseph and Mary). So it is also likely that when husbands died, many women remarried. This was true in ancient times: Boaz married the widow Ruth, David married the widow Bathsheba after Uriah was killed. It also seems likely to have been true in classical, 1 st century times: Paul (in Rom.7:1-3) suggests that this is at least somewhat common in the Jewish community (‘I speak to those under the Law’ he says) in the 1 st century. -

Athaliah, a Treacherous Queen: a Careful Analysis of Her Story in 2 Kings 11 and 2 Chronicles 22:10-23:21

Athaliah, a treacherous queen: A careful analysis of her story in 2 Kings 11 and 2 Chronicles 22:10-23:21 Robin Gallaher Branch School of Biblical Sciences & Bible Languages Potchefstroom Campus North-West University POTCHEFSTROOM E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Athaliah, a treacherous queen: A careful analysis of her story in 2 Kings 11 and 2 Chronicles 22:10-23:21 This article presents a critical look at the story of the reign of Athaliah, the only ruling queen of Israel or Judah in the biblical text. Double reference in 2 Kings and 2 Chronicles shows her story’s importance and significance to the biblical writers. The largely parallel accounts read like a contemporary soap opera, for they contain murder, intrigue, harem politics, religious upheaval, and coup and counter-coup. Her story provides insights on the turbulent political climate of the ninth century BC. However, the purpose of the biblical writers is not to show Athaliah as the epitome of evil or that all women in power are evil. Opsomming Atalia, ’n verraderlike koningin: ’n noukeurige analise van haar verhaal in 2 Konings 11 en 2 Kronieke 22:10-23:21 In hierdie artikel word die verhaal van Atalia krities nagegaan. Atalia was naamlik die enigste koninging van Israel of Juda wie se regeringstyd in die Bybelteks verhaal word. Die dubbele verwysings na hierdie tyd in 2 Konings en 2 Kronieke dui op die belangrikheid en betekenis van haar verhaal vir die Bybel- skrywers. Die twee weergawes wat grotendeels parallelle weer- gawes is, lees byna soos ’n hedendaagse sepie, want hierdie verhale sluit elemente in soos moord, intrige, harempolitiek, godsdiensopstand, staatsgreep en kontrastaatsgreep. -

The Interphased Chronology of Jotham, Ahaz, Hezekiah and Hoshea1 Harold G

THE INTERPHASED CHRONOLOGY OF JOTHAM, AHAZ, HEZEKIAH AND HOSHEA1 HAROLD G. STIGERS, Ph.D. Up until the appearance of The Mysteríous Numbers of the Hebrew Kings* by Edwin Thiele in 1951, the possibility of the harmonization of the dates for the Hebrew kings as given in the Book of Kings seemed impossibly remote, if not actually irreconcilable. The apparent conflict of data is seemingly due to the fact that an eye-witness account takes things as they are with no attempt being made to harmonize apparently contradictory data, nor to state outright the clues as to the relationships which would make it possible in an easy manner to coordinate the reigns of the kings. Living in the times of the kings of Israel and Judah, and understanding completely the circumstances, and writing a message, the significance of which is not dependent on the dates being harmonized, the authors of the records used in Kings felt no need of explaining coordinating data. However, if the dating were to be harmonized, the viewpoint that the present text of the Old Testament represents a careful transmission of the Hebrew text through the centuries3, would receive a great testi- mony to its accuracy. Now, with the work of Thiele, that testimony has, in a great measure, been given, but not without one real lack, in that for him, the chronology of the period of Jotham through Hezekiah is twelve years out of phase.4 In this point for him the chronology is contradictory and requires the belief that the synchronisms of 2 Ki. 18:9, 10 and 18:1 are the work of a later harmonizing hand, not in the autograph written by the inspired prophet.5 The method correlating the synchronizations between the Judean and Israelite kings of the time of 753/52 B.C. -

Josephus Writings Outline

THE WARS OF THE JEWS OR THE HISTORY OF THE DESTRUCTION OF JERUSALEM – BOOK I CONTAINING FROM THE TAKING OF JERUSALEM BY ANTIOCHUS EPIPHANES TO THE DEATH OF HEROD THE GREAT. (THE INTERVAL OF 177 YEARS) CHAPTER 1: HOW THE CITY JERUSALEM WAS TAKEN, AND THE TEMPLE PILLAGED [BY ANTIOCHUS EPIPHANES]; AS ALSO CONCERNING THE ACTIONS OF THE MACCABEES, MATTHIAS AND JUDAS; AND CONCERNING THE DEATH OF JUDAS. CHAPTER 2: CONCERNING THE SUCCESSORS OF JUDAS; WHO WERE JONATHAN AND SIMON, AND JOHN HYRCANUS? CHAPTER 3: HOW ARISTOBULUS WAS THE FIRST THAT PUT A DIADEM ABOUT HIS HEAD; AND AFTER HE HAD PUT HIS MOTHER AND BROTHER TO DEATH, DIED HIMSELF, WHEN HE HAD REIGNED NO MORE THAN A YEAR. CHAPTER 4: WHAT ACTIONS WERE DONE BY ALEXANDER JANNEUS, WHO REIGNED TWENTY- SEVEN YEARS. CHAPTER 5: ALEXANDRA REIGNS NINE YEARS, DURING WHICH TIME THE PHARISEES WERE THE REAL RULERS OF THE NATION. CHAPTER 6: WHEN HYRCANUS WHO WAS ALEXANDER'S HEIR, RECEDED FROM HIS CLAIM TO THE CROWN ARISTOBULUS IS MADE KING; AND AFTERWARD THE SAME HYRCANUS BY THE MEANS OF ANTIPATER; IS BROUGHT BACK BY ABETAS. AT LAST POMPEY IS MADE THE ARBITRATOR OF THE DISPUTE BETWEEN THE BROTHERS. CHAPTER 7: HOW POMPEY HAD THE CITY OF JERUSALEM DELIVERED UP TO HIM BUT TOOK THE TEMPLE BY FORCE. HOW HE WENT INTO THE HOLY OF HOLIES; AS ALSO WHAT WERE HIS OTHER EXPLOITS IN JUDEA. CHAPTER 8: ALEXANDER, THE SON OF ARISTOBULUS, WHO RAN AWAY FROM POMPEY, MAKES AN EXPEDITION AGAINST HYRCANUS; BUT BEING OVERCOME BY GABINIUS HE DELIVERS UP THE FORTRESSES TO HIM.