1999-2000 Report on Outreach Programs Introduction: Continued Works in Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pictured Aboved Are Two of UCLA's Greatest Basketball Figures – on The

Pictured aboved are two of UCLA’s greatest basketball figures – on the left, Lew Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) alongside the late head coach John R. Wooden. Alcindor helped lead UCLA to consecutive NCAA Championships in 1967, 1968 and 1969. Coach Wooden served as the Bruins’ head coach from 1948-1975, helping UCLA win 10 NCAA Championships in his 24 years at the helm. 111 RETIRED JERSEY NUMBERS #25 GAIL GOODRICH Ceremony: Dec. 18, 2004 (Pauley Pavilion) When UCLA hosted Michigan on Dec. 18, 2004, Gail Goodrich has his No. 25 jersey number retired, becoming the school’s seventh men’s basketball player to achieve the honor. A member of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, Goodrich helped lead UCLA to its first two NCAA championships (1964, 1965). Notes on Gail Goodrich A three-year letterman (1963-65) under John Wooden, Goodrich was the leading scorer on UCLA’s first two NCAA Championship teams (1964, 1965) … as a senior co-captain (with Keith Erickson) and All-America selection in 1965, he averaged a team-leading 24.8 points … in the 1965 NCAA championship, his then-title game record 42 points led No. 2 UCLA to an 87-66 victory over No. 1 Michigan … as a junior, with backcourt teammate and senior Walt Hazzard, Goodrich was the leading scorer (21.5 ppg) on a team that recorded the school’s first perfect 30-0 record and first-ever NCAA title … a two-time NCAA Final Four All-Tournament team selection (1964, 1965) … finished his career as UCLA’s all-time leader scorer (1,690 points, now No. -

31 Ed O'bannon #32 Bill Walton #11 Don Barksdale #25 Gail

RETIRED JERSEY NUMBERS #11 DON BARKSDALE during his professional career (a total that ranked first at the time and now ranks second to Ray Allen) ... Miller came to UCLA from an athletic family ... his brother Darrell played Ceremony: Feb 7, 2013 (Pauley Pavilion) catcher for the California Angels and now serves as MLB’s vice president of youth and UCLA retired the jersey of the late Don Barksdale at halftime facility development ... his sister Cheryl is a Hall of Fame women’s basketball player who of the Bruins’ 59-57 victory over Washington on Feb. 7, 2013. competed for the 1984 U.S. gold-medal winning Olympic women’s basketball team ... The Bruins celebrated the legacy of Barksdale on the court his sister Tammy played volleyball at Cal State Fullerton. in Pauley Pavilion before members of his family. UCLA won the contest that night on a buzzer-beating jump shot from #31 Ed O’BannON Larry Drew II before a crowd of 8,075. Ceremony: February 1, 1996 (Pauley Pavilion) Notes on Don Barksdale Ed O’Bannon’s jersey number was retired in a halftime A legendary African-American sports pioneer, Don Barksdale ceremony on Feb. 1, 1996, just the second such retirement was one of UCLA’s early superstars who could be described ceremony in school history. During halftime of the UCLA- as the “Jackie Robinson” of basketball ... he was the first Oregon contest, UCLA retired the numbers of O’Bannon African-American to earn All-America honors at UCLA (1947), the first to win an (31), along with No. -

Wilt Chamberlain's 100-Point Game 1 Wilt Chamberlain's 100-Point Game

Wilt Chamberlain's 100-point game 1 Wilt Chamberlain's 100-point game Wilt Chamberlain's 100-point game 1 2 3 4 Total Philadelphia 42 37 46 44 169 New York 26 42 38 41 147 Date March 2, 1962 Arena Hersheypark Arena City Hershey, Pennsylvania Attendance 4,124 Wilt Chamberlain's 100-point game, named by the National Basketball Association as one of its greatest games,[1] [2] was a regular-season game between the Philadelphia Warriors and the New York Knicks held on March 2, 1962 at Hersheypark Arena in Hershey, Pennsylvania. The Warriors won the game 169–147, setting what was then a record for the most combined points in a game by both teams. The game is most remembered, however, for the 100 points scored by Warriors center Wilt Chamberlain. This performance ranks as the NBA's single-game scoring record; along the way Chamberlain also broke five other NBA scoring records, of which four still stand. As Chamberlain broke several other scoring records during the 1961–62 NBA season, his 100-point performance was initially overlooked. In time, however, it became his signature game. Cover of Wilt, 1962 by Gary M. Pomerantz (2005), which draws parallels between Chamberlain's legendary 100-point game and the rising of Black America. Wilt Chamberlain's 100-point game 2 Prologue Chamberlain, the Warriors' star center, was on a unique scoring spree. He had already scored 60 or more points a record 15 times in his career. On December 8, 1961, in a triple overtime game versus the Los Angeles Lakers, he had set a new NBA record by scoring 78 points, eclipsing the previous mark of 71 held by the Lakers' Elgin Baylor. -

Pero's Seasoned

X . ^ { r ‘ - . .4 * 4 './ V -■ '■■■>■ '. .. , r: ‘ 1 ■-. ■ PAGE FpURTEEN illattrh fa trr lEtt^tthtg firra lb SA OCTOBER 2B, 198K police of a changtrof address," he ton, Bible study leader, yvlll speak replied, "Which one would you Service Series ^ on the Book of BevelattonS. A bou t T^owii like?" '.s' ' Neighborhood' committees from Heard AUpng Main Street Being Planned’ Lower Hebron Ava, Diamond Heancea Tuesday The 2nd Missile Bn. par«de Lake, Mancheater Rd. and. Oedari which was rained out at Mt. Nebo And on Sntno of IHanrhonter*a Sido Strt'OtB, Too The Herald's theater reporter picked up the. phone this morning In Buckingham Ridge are aaalsting in this second Field Thursday has been sched series of church nights. Attend-i uled to take place W>dnesday. to hear a man's voice say, "This is the ghost of Glenn Miller, I want The Rev. Philip M, Roee of ants of other Glastonbury churches The parade is part of a ceremony Penny for His Thoughts ^ "Why don't you knock It down, are Invited. The programs have to honor M. .Ss:t. Floyd E. Hal One dime, two nlcklee, end live Ed 7" the friend called Jokingly, to talk to the entertainment edi the Buckingham C^nirr«jgAtional tor," been planned by and are under stead who retires Oct. 31. pennies make 29 cents—exactly Whereupon Rybciyk drew him Church Announcea a scries of four auspices of the Bubkingham. self up to his fi.ll 6 feet 2, hefted •fVou'll have to watt your turn, PJNE LENOX 29 cents. -

Stands As UCLA's All-Time Scoring Leader (2608 Points). Bill Walton

Don MacLean (left) stands as UCLA’s all-time scoring leader (2,608 points). Bill Walton (center) owns the program’s career rebounds record (1,370). He finished his career averaging 15.7 rebounds per game. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (then known as Lew Alcindor) ranks second in career points (2,325) and career rebounds (1,367) but leads all UCLA players with 26.4 points per game. 119 UCLA RECORDS Individual – Career Most Games 147 Michael Roll 2006-2010 Most Starts 134 Josh Shipp 2004-2009 Most Points 2,608 Don MacLean 1989-1992 Highest Scoring Average 26.4 Lew Alcindor 1967-1969 Most Rebounds 1,370 Bill Walton 1972-1974 Highest Rebounding Average 15.7 Bill Walton 1972-1974 Most Field Goals 943 Lew Alcindor 1967-1969 943 Bill Walton 1972-1974 Most FG Attempts 1,776 Don MacLean 1989-1992 Highest FG Pct. 69.4 pct Jelani McCoy 1996-1998 Most 3-Point FGs 317 Jason Kapono 2000-2003 Most 3-Point FG Attempts 710 Jason Kapono 2000-2003 Pooh Richardson Darren Collison Highest 3-Point FG Pct. 46.6 pct Pooh Richardson 1986-1989 Most Free Throws 711 Don MacLean 1989-1992 Team – Season Most Free Throw Attempts 827 Don MacLean 1989-1992 Most Points 3,003 2014 Highest Free Throw Pct. 88.0 Rod Foster 1980-1983 Highest Scoring Average 94.6 1972 Most Assists 833 Pooh Richardson 1986-1989 Most Rebounds 1,670 1964 Most Steals 235 Earl Watson 1998-2001 Highest Rebound Average 55.7 1964 Most Blocked Shots 188 Jelani McCoy 1996-1998 Most Field Goals 1,161 1968 Most Minutes Played 4,371 Earl Watson 1998-2001 Most Field Goal Attempts 2,335 1950 Most League Points 1,486 -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E2168 HON

E2168 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks December 8, 2006 I also would like to thank members of my basketball and the nation will be forever re- by the BLM unless significant recreation serv- staff who worked on this issue including Chris- membered. ices are provided. This provision will help the tine Kojac and Mike Ringler of the Science- f public access the Bend Area free of charge for State-Justice-Commerce appropriations sub- activities like an afternoon hike or bike ride. committee, and Janet Shaffron and Samantha THE SACRAMENTO RIVER NA- Any modest fees that could be charged at the Stockman of my personal staff. A special TIONAL RECREATION AREA ES- Bend Area would be developed in consultation thanks goes to my chief of staff, Dan TABLISHMENT ACT OF 2006 with the public and proceeds would be rein- Scandling, who accompanied me on my trips vested in local recreation and safety facilities. to Iraq and served as photographer and writer HON. WALLY HERGER Local involvement and participation is also for the trip reports. OF CALIFORNIA required in the bill. The legislation would es- f IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES tablish an ‘‘Advisory Council’’ to ensure that Thursday, December 7, 2006 the ideas and concerns of local citizens are in- HONORING THE LIFE OF ARNOLD corporated into a management plan for the ‘‘RED’’ AUERBACH Mr. HERGER. Mr. Speaker, today I am in- area. The Advisory Council would be ap- troducing the Sacramento River National pointed by locally elected officials, and would SPEECH OF Recreation Area Establishment Act of 2006. consist of concerned citizens representing di- HON. -

Men's Basketball Release

MEN'S BASKETBALL RELEASE UCLA Men’s Basketball Feb. 3, 2005 Marc Dellins/Bill Bennett/310-206-8179 For Immediate Release UCLA(11-6 OVERALL,5-4 PAC-10/4TH-PLACE) TRAVELS TO WASHINGTON SCHOOLS THIS WEEK FOR TWO PAC-10 ENCOUNTERS – AT WSU(9-9,4-5,5TH-PLACE TIE) THURSDAY(FEB. 3/7:30P.M.) AND AT NO. 13 UW (17-3,7-2,1ST-PLACE TIE) SATURDAY(FEB. 5/2P.M.); LAST SATURDAY(JAN. 29), BRUINS SNAP THREE-GAME CONFERENCE LOSING STREAK, COMING BACK FROM AN 18-POINT HALFTIME DEFICIT TO WIN AT ARCHRIVAL USC(72-69) UCLA'S NEXT GAMES Tournament Championship and in 2002, Pittsburgh was THURSDAY, FEB. 3 – UCLA(11-6 Overall, 5-4 29-6 overall (school record for wins), advanced to the Pac-10/4th-place) at WASHINGTON STATE(9-9 NCAA "Sweet 16" and the Big East Tournament title Overall,4-5 Pac-10/5TH-place tie) - Pullman, WA, game and Howland was the consensus National Coach of Friel Court, 7:30p.m.PT(TV-FSN/Radio-Fabulous 690, the Year. with Chris Roberts and Don MacLean). UCLA STAFF - Joining Howland are assistant coaches, SATURDAY, FEB. 5 – UCLA at No. 1 3 all entering their second season - Donny Daniels, who WASHINGTON(17-3 Overall,7-2 Pac-10/1st- was head coach at CS Fullerton for three seasons (2000-03); place tie, UW hosts USC on Feb. 3) – Seattle, Ernie Zeigler, who for two years (2002-03) served on WA, Hec Edmondson Pavilion, 2 p.m.PT(TV-FSN/Radio- Howland's Pittsburgh staff and Kerry Keating, who for XTRA Sports 570, with Chris Roberts and Don MacLean). -

Violence Spreads in Belgian Crisis

J . I Weather Distribution I Clearing today; high about RED BANK Today 44. Fair tonight; low 25-30. Fair tomorrow; high about 40. 1 Independent Daily f 16,600 See tides and weather page 2. (^ MONDAY THKOUGH fKtBAY-tST. Ml J VOL. 83, NO. 128 Issued Dally. Monday throucti Friday, intered •• Second CI»M Matter RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, DECEMBER 30, 1960 7c PER COPY 35c PER WEEK at tha Post Olllce at Red Bank, N. J.. under the Act of March 3. 1879. BY CARRIER PAGE ONE Rain Turns Snow Into Icy Slush Violence Spreads LONG BRANCH — Two inches of snow which fell early yesterday turned to slush last night as a steady rain fell on the area. The rain, which left roads slippery, saved the area from another crippling snowstorm. In Belgian Crisis William D. Martin, U. S. weather observer, said the .58 inches of rain — had it been snow — would have amounted Airline to a fall of to about six and one-half inches. No serious accidents from the hazardous road conditions were Office reported, but police were main taining a watchful eye and road crews were sanding inter- sections. Stoned The weatherman promised Putting Snow To Good Use temperatures about 40 degrees BRUSSELS, Belgium today and tomorrow. Slow (AP) — Saber-swinging The weather'$ fine, although motorists may have had different views about yester- clearing today will be followed by fair skies tonight and to- mounted police today drove day's light snowfall, these Fair Haven youngsters thought it was just fine. The win- morrow. back marching strikers who ter wonderland producers, who used Christmas greens and wrappings to^ decorate stoned the Brussels head- seven snowmen, all live on Woodland Dr. -

Los Angeles High Schools Sports Hall of Fame

INAUGURAL INDUCTION CEREMONY JUNE 5, 2011 LOS ANGELES HIGH SCHOOLS SPORTS HALL OF FAME n behalf of the Los Angeles Unified School District and CIF Los Angeles City Section, I would O like to welcome you to the Induction Ceremony for the Inaugural Class of the Los Angeles High Schools Sports Hall of Fame! The Los Angeles City High School District was founded way back in 1890. Although high school sports have been a part of our schools for more than a century, there has never been true recognition given to the thousands of prominent athletes, coaches and contributors to the world of sport who have come through our schools. Some of the members honored tonight are Super Bowl Champion John Elway, Cy Young Winner Don Drysdale, Eight-Time CIF Champion Basketball Coach Willie West, US Open Champion Golfer Amy Alcott, Wrestling Hall of Famer Jack Fernandez, NBA All-Star Willie Naulls, NCAA Champion and USC Hall of Fame Gymnast Makoto Sakamoto, Two-time Olympic Softball Gold Medalist Sheila Cornell Douty, and Football and Track standout Tom Bradley, longest serving mayor in Los Angeles City history! This class also includes the U.S. Open Tennis Champion from 1912-14, an NCAA “Coach of the Century”, a U.S. National Soccer Player of the Year, a triple-gold medal winner in the 1984 Olympics, the first American women under 50 seconds in the 440, the “Godfather of Lithuanian Basketball”, a four-time WNBA Champion and MVP, a 400 Meter CIF Track and Olympic Champion, as well as the First African American Major League Baseball Umpire, and the first Asian American Olympic Gold Medal winner. -

Mtrack 50-63.Indd

HEAD COACHING HISTORY Since 1919, the UCLA men’s track team has been successfully led by six men - Harry Trotter, Elvin C. “Ducky” Drake, Jim Bush, Bob Larsen, Art Venegas and now, Mike Maynard. Behind these men, the Bruins have won eight National Championships, ranging from 1956 to 1988. Harry “Cap” Trotter - 1919 to 1946 Trotter started coaching the track team in 1919, the year UCLA was founded, and was called upon to coach the football team from 1920-1922. During his tenure as head track coach, Trotter produced numerous prominent track and fi eld athletes. The pride of his coaching career were sprinter Jimmy LuValle and his successor, Elvin “Ducky” Drake. Elvin C. “Ducky” Drake - 1946 to 1964 In 19 seasons under Elvin “Ducky” Drake, UCLA had a dual meet record of 107-48-0 (.690) and won one NCAA Championship and one Pac-10 title. Drake was a charter member into the UCLA Hall of Fame in 1984 and was inducted inducted into the USA Track & Field Track & Field Hall of Fame in December of 2007. In 1973, the Bruin track and fi eld complex was offi cially named “Drake Stadium” in honor of the UCLA coaching legend who had been associated with UCLA as a student-athlete, coach and athletic trainer for over 60 years. Some of Drake’s star athletes include Rafer Johnson, C.K. Yang, George Stanich, Craig Dixon and George Brown. Jim Bush - 1965 to 1984 Bush had incredible success during his 20 years as head coach, as UCLA won fi ve NCAA Championships, seven Conference Championships and seven national dual meet titles under his guidance. -

Ncaa Men's Basketball's Finest

The NCAA salutes 360,000 student-athletes participating in 23 sports at 1,000 member institutions NCAA 48758-10/05 BF05 MEN’S BASKETBALL’S FINEST THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION P.O. Box 6222, Indianapolis, Indiana 46206-6222 www.ncaa.org October 2005 Researched and Compiled By: Gary K. Johnson, Associate Director of Statistics. Distributed to Division I sports information departments of schools that sponsor basketball; Division I conference publicity directors; and selected media. NCAA, NCAA logo and National Collegiate Athletic Association are registered marks of the Association and use in any manner is prohibited unless prior approval is obtained from the Association. Copyright, 2005, by the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Printed in the United States of America. ISSN 1521-2955 NCAA 48758/10/05 Contents Foreword ............................................................ 4 Players................................................................ 7 Player Index By School........................................168 101 Years of All-Americans.................................174 Coaches ..............................................................213 Coach Index By School........................................288 On the Cover Top row (left to right): Tim Duncan, Bill Walton, Michael Jordan and Oscar Robertson. Second row: Jerry West, Dean Smith, James Naismith and Isiah Thomas. Third row: Bill Russell, Shaquille O’Neal, Carmelo Anthony and John Wooden. Bottom row: Tubby Smith, Larry Bird, Lew Alcindor (Kareem Abdul- Jabbar) and David Robinson. – 3 – Foreword Have you ever wondered about how many points Michael Jordan scored at North Carolina? Or how many shots were swatted away by Shaquille O’Neal at LSU? What kind of shooting percentage did Bill Walton have at UCLA? What was John Wooden’s coaching won-lost record before he went to UCLA? Did former Tennessee coach Ray Mears really look like Cosmo Kramer? The answers to these questions and tons more can be found in these pages. -

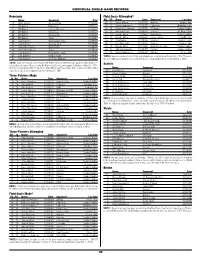

Rebounds Three-Pointers Made Three-Pointers Attempted Field

INDIVIDUAL SINGLE-GAME RECORDS Rebounds Field Goals Attempted* Name Opponent Date Att. FG Name Date Opponent Location 28 Willie Naulls Arizona State 01/28/56 27 13 Trevor Wilson 03/11/90 Arizona Tempe, Ariz. 27 Bill Walton Maryland 12/01/73 27 16 David Greenwood 01/13/77 California Berkeley, Calif. 27 Bill Walton Loyola (Chicago) 01/25/73 25 14 Raymond Townsend 03/05/78 Michigan Pauley Pavilion 24 Bill Walton Providence 01/20/73 25 12 Aaron Holiday 03/08/18 Stanford Las Vegas, Nev. 24 Bill Walton Washington 02/12/72 25 10 Reggie Miller 01/29/87 Washington Pauley Pavilion 24 Bill Walton Texas 12/29/71 25 16 Reggie Miller 03/06/86 Oregon State Corvallis, Ore. 24 Lew Alcindor Washington State 02/25/67 24 7 Toby Bailey 01/17/98 Stanford Stanford, Calif. 24 Lew Alcindor Georgia Tech 12/29/66 24 12 Don MacLean 01/26/91 Oregon Eugene, Ore. 23 David Greenwood Washington 01/06/78 24 15 Reggie Miller 02/09/86 Washington State Pauley Pavilion 23 David Greenwood Tulsa 12/18/76 24 13 Kiki Vandeweghe 12/15/79 DePaul Pauley Pavilion 23 Lew Alcindor New Mexico State 03/15/68 24 17 David Greenwood 03/17/79 DePaul Provo, Utah 23 Lew Alcindor Oregon State 02/18/67 *NOTES: Game-by-game records of field goal attempts are complete back through the 1976-77 season. 23 Lew Alcindor UC Santa Barbara 01/21/67 Most recently, Isaac Hamilton had 23 attempts (made seven) against Oregon State (March 5, 2016).