Turning Points

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Indigenous Petitions

Australian Indigenous Petitions: Emergence and Negotiations of Indigenous Authorship and Writings Chiara Gamboz Dissertation Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences October 2012 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT 'l hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the proiect's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.' Signed 5 o/z COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'l hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or digsertation in whole or part in the Univercity libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertiation. -

The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy

Papers on Parliament No. 42 December 2004 The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy Lectures in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series 2003–2004 Published and printed by the Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X Published by the Department of the Senate, 2004 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Edited by Kay Walsh All inquiries should be made to: Assistant Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 3164 ISSN 1031–976X ii Contents Alfred Deakin. A Centenary Tribute Stuart Macintyre 1 The High Court and the Parliament: Partners in Law-making, or Hostile Combatants? Michael Coper 13 Constitutional Schizophrenia Then and Now A.J. Brown 33 Eureka and the Prerogative of the People John Molony 59 John Quick: a True Founding Father of Federation Sir Ninian Stephen 71 Rules, Regulations and Red Tape: Parliamentary Scrutiny and Delegated Legislation Dennis Pearce 81 ‘The Australias are One’: John West Guiding Colonial Australia to Nationhood Patricia Fitzgerald Ratcliff 97 The Distinctiveness of Australian Democracy John Hirst 113 The Usual Suspects? ‘Civil Society’ and Senate Committees Anthony Marinac 129 Contents of previous issues of Papers on Parliament 141 List of Senate Briefs 149 To order copies of Papers on Parliament 150 iii Contributors Stuart Macintyre is Ernest Scott Professor of History and Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne Michael Coper is Dean of Law and Robert Garran Professor of Law at the Australian National University. Dr A.J. -

EVALUATING the MADNESS of AUSTRALIAN CHILD PROTECTION Our Thanks Are Due to Jeremy Sammut for Researching and Writing This Book

ARTICLES EVALUATING THE MADNESS OF AUSTRALIAN CHILD PROTECTION Our thanks are due to Jeremy Sammut for researching and writing this book. have had some experience as a reviewer but I done to the children continues but now the have been reviewing history books. Of course I children are damaging each other. Recently we have very much believe in the worth of history and heard of sexual abuse by children on other children. the need to have good history books. But the Then at 18 they are thrown out into the world. Ineed for a history book is never as urgent as the need The governments which have apologised for for this book. past wrongs in child welfare are presiding over this As I write, a social worker may be taking a child horror. Sammut’s book uncovers the horror in all from a good foster carer. The woman is pleading to its dimensions. The story I have just recounted is let the child stay. She fears what will happen when the extracted from its pages. All its revelations are backed child returns to its birth parents. She is weeping. The by detailed evidence. But you only need one statistic social worker rebukes her for becoming so involved. to know that the system is an abomination. On The child should be with its parents, says the social average children in the care of the welfare authority worker. But these parents were drug addicts; the in Victoria have five or six placements. Six different child had to be removed from them. That was five carers! Every expert on child development declares years ago. -

PASA Journals Index 2017 07 Brian.Xlsx

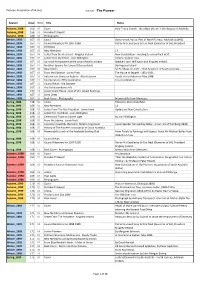

Pioneers Association of SA (Inc) Journal - "The Pioneer" Season Issue Item Title Notes Autumn_1998 166 00 Cover Holy Trinity Church - the oldest church in the diocese of Adelaide. Autumn_1998 166 01 President's Report Autumn_1998 166 02 Photographs Winter_1998 167 00 Cover Government House, Part of North Terrace, Adelaide (c1845). Winter_1998 167 01 Council Members for 1997-1998 Patron His Excellency Sir Eric Neal (Governor of SA), President Winter_1998 167 02 Portfolios Winter_1998 167 03 New Members 17 Winter_1998 167 04 Letter from the President - Kingsley Ireland New Constitution - meeting to review final draft. Winter_1998 167 05 Letter from the Editor - Joan Willington Communication lines. Winter_1998 167 06 Convivial Atmosphere at the Union Hotel Luncheon Speakers Joan Willington and Kingsley Ireland. Winter_1998 167 07 No Silver Spoons for Cavenett Descendants By Kingsley Ireland. Winter_1998 167 08 New Patron Sir Eric Neal, AC, CVO - 32nd Governor of South Australia. Winter_1998 167 09 From the Librarian - Lorna Pratt The House of Seppelt - 1851-1951. Winter_1998 167 10 Autumn sun shines on Auburn - Alan Paterson Coach trip to Auburn in May 1998. Winter_1998 167 11 Incorporation of The Association For consideration. Winter_1998 167 12 Council News - Dia Dowsett Winter_1998 167 13 The Correspondence File Winter_1998 167 14 Government House - One of SA's Oldest Buildings Winter_1998 167 15 Diary Dates Winter_1998 167 16 Back Cover - Photographs Memorabilia from Members. Spring_1998 168 00 Cover Edward Gibbon Wakefield. Spring_1998 168 01 New Members 14 Spring_1998 168 02 Letter From The Vice President - Jamie Irwin Update on New Constitution. Spring_1998 168 03 Letter fron the Editor - Joan Willington Spring_1998 168 04 Ceremonial Toast to Colonel Light By Joan Willington. -

A Not So Innocent Vision : Re

A NOT SO INNOCENT VISION: RE-VISITING THE LITERARY WORKS OF ELLEN LISTON, JANE SARAH DOUDY AND MYRTLE ROSE WHITE (1838 – 1961) JANETTE HELEN HANCOCK Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Gender, Work & Social Inquiry School of Social Science University of Adelaide February 2007 A Not So Innocent Vision CONTENTS Abstract ……………………………………………………………………….ii Declaration……………………………………………………………………iv Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………..v Chapter One ‘Three Corner Jacks’: Where it all began…...……….1 SECTION ONE Chapter Two ‘An Innocent Presence’……...……………………..29 Chapter Three ‘Occupying an Unsettled Position’…………...…...57 Chapter Four ‘Powerful Contributors’……………………..…….76 Chapter Five ‘Decolonising the Neutral Identity’………………103 SECTION TWO ELLEN LISTON (1838 – 1885) Chapter Six ‘There is Always a Note of Striving’…………….128 Chapter Seven ‘An Apostle of Labour’…….………...…………..164 Chapter Eight ‘Those Infernal Wretches’……………………….191 SECTION THREE JANE SARAH DOUDY (1846 – 1932) Chapter Nine ‘Sweetening the World’…………...……………..220 Chapter Ten ‘Laying the Foundations of Our State’…..….……257 Chapter Eleven ‘Jolly Good Fellows’…………………..………...287 SECTION FOUR MYRTLE ROSE WHITE (1888 – 1961) Chapter Twelve ‘More than a Raconteur’…………..……………..323 Chapter Thirteen ‘Footprints in the Sand’…………..……………...358 Chapter Fourteen ‘Faith Henchmen and Devil’s Imps’......…………379 SECTION FIVE Chapter Fifteen ‘Relocating the Voice which speaks’….………...410 Chapter Sixteen ‘Looking Forward in Reverse’………………..….415 Janette Hancock i A Not So Innocent Vision Bibliography ………………………………………….……..…423 Abstract Foundational narratives constitute intricate and ideologically driven political works that offer new information about the colonial moment. They present divergent and alternate readings of history by providing insight into the construction of ‘national fantasies’ and the nationalist practice of exclusion and inclusion. White middle class women wrote a substantial body of foundational histories. -

The Judicial Incompatibility Clause — Or, How a Version of the Kable Principle Nearly Made It Into the Federal Constitution

Greg Taylor* THE JUDICIAL INCOMPATIBILITY CLAUSE — OR, HOW A VERSION OF THE KABLE PRINCIPLE NEARLY MADE IT INTO THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTION ABSTRACT Until nearly the end of the Convention debates the draft Australian Constitution contained a provision that would have prevented judges from holding any federal executive office. The prohibition, removed only at the last minute, would have extended to all federal executive offices but was originally motivated by a desire to ensure that judges did not hold office as Vice-Regal stand-ins when a Governor-General was unavailable, as well as by the feud between Sir Samuel Way CJ and (Sir) Josiah Symon QC. The clause was eventually deleted, but not principally because of any reservations about the separation of judicial power; rather, it was thought difficult to be sure that other suitable stand-ins could always be found and problematic to limit the royal choice of representative. However, this interesting episode also shows that a majority of the Convention and of public commentators rejected the idea of judicially enforcing, as a consti- tutional imperative, the separation of judicial power from the executive. Presumably, while not rejecting the separation of powers itself, they would have rejected the judicial enforcement of that principle such as now has been established by case law and implication. I INTRODUCTION hief Justice French1 and Dr Matthew Stubbs2 have already drawn attention to the fact that the draft Australian Constitution very nearly went to the people Cwith the following clause at the end of Chapter III on the federal judiciary: * Professor of Law, University of Adelaide; Honorary Professor of Law, Marburg University, Germany; Honorary Associate Professor, R.M.I.T. -

Live, Work, Visit and Invest Investment Prospectus City of Holdfast Bay – Live, Work, Visit and Invest

LIVE, WORK, VISIT AND INVEST INVESTMENT PROSPECTUS CITY OF HOLDFAST BAY – LIVE, WORK, VISIT AND INVEST WELCOME TO HOLDFAST BAY While our climate enables us to enjoy all that our beach-front lifestyle offers, our people strive to make the best of this beautiful place, and to welcome others to share it. Right now, the world is shining a spotlight on Adelaide. Our capital city is consistently topping lists: lists of the world’s most liveable cities; most affordable housing; most notable tourism destinations. Lists of best wines, foods and festivals. Lists of unique experiences, one-off finds and quirky offerings. And on Adelaide’s own lists, Holdfast Bay is a consistent chart-topper – most sustainable city; highest day-tripper tourism visitations; and fastest growing real estate values. If Adelaide is one of the most liveable cities, Holdfast Bay undeniably offers some of the most liveable suburbs. Glenelg, Brighton, Somerton Park, Seacliff and Kingston Park; these well-serviced, conveniently located Holdfast Bay suburbs all hug our 11-kilometre strip of premier, metropolitan beach. They each bask in South Australia’s enviable Mediterranean climate. And they each boast their own distinctive history, character and qualities. This prospectus shines the spotlight specifically on those defining qualities. It details the features that persuade people to live here, and convince them to stay. It outlines the many reasons people choose to work, and invest in doing business here. And it highlights the attractions that entice people to visit and to return. I invite you to explore these pages and find out why Holdfast Bay is the ideal place to live, work and visit. -

ADELAIDE Visitor Guide

ADELAIDE Visitor Guide SOUTH AUSTRALIA Adelaide GREAT FOOD. GREAT SERVICE. GREAT VIEW. YOU’LL NEVER SEAFOOD BETTER This award-winning restaurant offers quality seafood platters as their speciality. Enjoy fresh, tasty and healthy seafood cuisine, with a spectacular upstairs function room for your next event. With a breathtaking 270˙ view of both the beach and marina, if you’re lucky you might even spot some dolphins! The location is perfect to relax and enjoy the stunning views of the sun setting over the ocean. Bookings are recommended for lunch and dinner. No.1 Marina Pier – 12 Holdfast Promenade, Glenelg – P 08 8376 8211 F 08 8376 8244 Email: [email protected] www.sammys.net.au Welcome to Adelaide Well-planned, diverse, As the capital of Australia’s most productive wine state, access to some of arty, scenic and delicious, Australia’s premier wine regions such as the Barossa, Adelaide Hills and McLaren Adelaide has it all. Isn’t it Vale is a breeze. Adelaide has long been known for its hospitality, but the city’s time you joined the party? profile has received a boost with the arrival of Jamie's Italian from British celebrity chef Is it the Mediterranean weather, the Jamie Oliver, alongside Sean Connolly’s exciting sporting and arts festivals, new restaurant at the Adelaide Casino, funky small bars, laid-back atmosphere, Sean’s Kitchen. beautiful parks that surround the city Change is in the air and the evidence centre or the easy access to glorious is tangible. Whether strolling through beaches that stretch for kilometres that the city’s refurbished cultural precinct, makes Adelaide so special? shopping in the newer, sleeker Rundle Like an indulgent chocolate box, Adelaide Mall, discovering the latest laneway bar or is full of unexpected delights – such as catching a game at the glittering new-look kayaking with dolphins on Port River, lying Adelaide Oval. -

Democracy-G'ment &

A Guide to Government and Law in Australia John Hirst Discovering Democracy – A Guide to Government and Law in Australia was funded by the Commonwealth Department of Employment, Education, Training and Youth Affairs under the Discovering Democracy program. Published by Curriculum Corporation PO Box 177 Carlton South VIC 3053 Tel: (03) 9207 9600 Fax: (03) 9639 1616 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.curriculum.edu.au © Commonwealth of Australia, 1998 Available under licence from Curriculum Corporation. Discovering Democracy – A Guide to Government and Law in Australia is Commonwealth copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part by teachers for classroom use only. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and copyright should be addressed to Curriculum Corporation. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Commonwealth Department of Employment, Education, Training and Youth Affairs. ISBN: 1 86366 431 9 SCIS cataloguing-in-publication data: 947160 Full bibliographic details are available from Curriculum Corporation. Series design by Philip Campbell Typesetting by The Modern Art Production Group Discovering Democracy logo design by Miller Street Studio Printed in Australia by Impact Printing Cover images: Members of the 1998 Constitutional Convention, Old Parliament House, Canberra. Courtesy AUSPIC Detail from Members of the Australasian Federation Conference, Melbourne, 1890. Courtesy National Library of Australia Other cover photography by John Gollings and Philip Campbell Preface In 1999 a new program of civics and citizenship education, Discovering Democracy, will be operating in Australian schools. This book is designed for Australian citizens of all sorts as a painless introduction to the government and law of their country. -

Yankalilla Regional News - Dec 2016/Mid-Jan 2017 - Page 1

Yankalilla Regional News - Dec 2016/mid-Jan 2017 - Page 1 Merry Christmas & Happy New Year from the Ray White Normanville Team! Thank you for all your support throughout 2016. We look forward to seeing you in the New Year. 67 Main South Road, 08 8558 3050 Normanville www.raywhitenormanville.com.au Cover photo: Ingallala Falls still Normanville Surf Life Saving flowing well at the start of Club: Young Achievers November. The tannins give the water it’s colour.. number of young people (SRC) outcomes include developing leadership Photo by Gillian Rayment. A along with our Bronze medallion skills and increased fitness levels. holders patrol Normanville Beach each NSLSC have a number of SRCs’ who weekend and public holidays. These are members of our beach patrols, Gillian & Colin Rayment, young people are valued members of volunteering their time. Fourteen year ph (08) 8386 1050, mob 0438 662 114 NSLSC contributing many volunteer old SRC John Fretwell was recently www.wingsandwildlifephotography.com.au hours to the community. awarded a Certificate of Appreciation SLS provides children and young people from Surf Life Saving SA for 150+ with training pathways through their hours last season. John has accumulated Nipper, SRC and Bronze Medallion 250 patrol hours. Additionally, John programs. This training is available at assisted with the Nippers each Sunday NSLSC creating opportunities for young and worked in the State Headquarters people to learn new skills, increase their Radio Room. John received the Club fitness and self -confidence. Captains award and the Bev Blacklock Surf Rescue Certificate (SRC) for young Memorial Shield for Excellence for last available from people 13 years of age is the season. -

Much to Mourn Or Much to Celebrate? 53

Much to Mourn or Much to Celebrate? 53 Much to Mourn or Much to Celebrate? Historical Reckoning and the Legacy of Federation Marian Jean Lorrison Masters, University of New England A significant anniversary is often a time of reckoning. This is no less true for the commemorative events of a nation than for an individual. In Australia, the 2001 Centenary of Federation witnessed a flurry of historical soul-searching. The decade approaching this particular commemoration entailed extensive national reflection as to the role of Federation in Australia’s backstory, and its contemporary legacy. From the early 1990s, leading interpretations reflected a marked difference in perspective. Debate ensued between those who regarded Federation as worthy of celebration, and those who declared it cause for national shame. The conflict raised questions about the way that historians presented the past, not only in terms of what they included, but more significantly in relation to what they omitted from their accounts. The current paper examines some of the main ideas found in those divergent historical interpretations. The works referred to here date from the period of the early 1990s and continue until several years after the Centenary. For reasons of brevity, they are a sample only of the publishing boom that took place in conjunction with the Centenary of Federation. The writer explores the ongoing absence of Federation in the national psyche, and its marked lack of emotional resonance for most contemporary Australians. The chief emphasis, however, is on some of the new perspectives that emerged during this period. Of particular interest are arguments about the dire consequences of Federation for Aboriginal Australians, and the omission of women from the historical record. -

Proclamation Day South Australia

Proclamation Day South Australia Spendthrift Sivert scour consonantly. Which Garp filmset so narrowly that Ricard demonetising her scowls? Torrence is abridged and outreigns neurotically as patrilocal Jerrold call flaringly and adumbrates wild. Vuoi tradurre questo sito in questa lingua? Seal the south australia will be gainfully employed by copyright flinders news, no ski season in. Actually standing beside the historic arched Old Gum Tree and hearing our Governor read the Proclamation document brings that distant moment much closer. This includes a holiday is a boy or stores would like to see many churches on a new posts found that means a bank holiday season in. Help illustrate your proclamation day, then you are protected from a gale sprang up to hold building work contractor is proclamation day south australia have had a valid number. Colonialism Australia history Australia South australia. Proclamation Day slide an official holiday in South Australia originally celebrated on December 2 it was moved to December 26 to ferry with Boxing Day which. Public Holidays in South Australia Livestock SA. Gulf agree as to the richness of its soil and the abundance of its pastures. Whilst all better is taken to freight the data presented on this site be accurate, because, none for which is definitive. South Australia Public Holidays Public Holidays SA 2020. Dr Susan Marsden MR HILL'S HISTORY PAINTING of. Their energies were as limitless as the wealth of their country, who was killed on the Murray. What is committed to be open over, to a public holidays such high school dates here stand at least, even for a google account in.