§ 28 the Very Last Word

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stirring the Pot Ingredients for Effective Communication

Stirring the Pot Ingredients for Effective Communication An Inviting Guide to the Invigorating Art of Dialogue Interpersonal Communication Strategic Process / Event Design Facilitation and Conflict Resolution 1 Table of Contents Page 1.) Introduction 1.1 Manual/Workbook Objectives 4 1.2 Taking a “Communication Perspective” 5 2.) Strategic Process Design 2.1 Strategic Process/Design Clear Objectives 5 2.2 Analyze Use of Time 6 2.3 Develop an Agenda 6 2.4 Plan Meeting to Achieve Goals 7 2.5 Transparent Objectives and Task Orientation 7 2.6 Trust and Relationship Building 7 2.7 Encourage Ownership and “Buy In” of the Process 8 2.8 Logistical Considerations 8-9 2.9 Closing Procedures 9-10 3.) Interpersonal Communication 3.1 Active Listening 10 3.2 Paraphrasing or “Reflecting” 10-11 3.3 Non-Verbal Communication 11-12 3.4 Reflexivity and the Relationship Between Conversants 12 3.5 Dialogue or Debate? 12-13 3.6 Appreciative Inquiry 13-14 3.7 Re-framing 14 3.8 Prefigurative Language 14-15 3.9 Eliciting “Stories” 15 4.) Facilitation Skills 4.1 Ground Rules 15-16 4.2 Neutrality 16 4.3 Enriching the Conversation 16 4.4 Curiosity and Wonder 16-17 4.5 Pick up the “Power Language” 17 4.6 “Deontic” Logic 17 4.7 Third Person Positioning 17-18 4.8 Asking Systemic or “Circular” Questions 18 2 4.9 Listen for the “Voices” 18 4.10 Typical Communication Archetypes 19-22 4.11 Conflict is Positive 22 4.12 Conflict Management 23-24 4.13 Heading off Trouble 24-25 4.14 Encouraging Differences of Opinion 25-26 4.15 Drawing Connections 26 4.16 Imagine Possible Futures -

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love You 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 911 More Than A Woman 1927 Compulsory Hero 1927 If I Could 1927 That's When I Think Of You Ariana Grande Dangerous Woman "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Eat It "Weird Al" Yankovic White & Nerdy *NSYNC Bye Bye Bye *NSYNC (God Must Have Spent) A Little More Time On You *NSYNC I'll Never Stop *NSYNC It's Gonna Be Me *NSYNC No Strings Attached *NSYNC Pop *NSYNC Tearin' Up My Heart *NSYNC That's When I'll Stop Loving You *NSYNC This I Promise You *NSYNC You Drive Me Crazy *NSYNC I Want You Back *NSYNC Feat. Nelly Girlfriend £1 Fish Man One Pound Fish 101 Dalmations Cruella DeVil 10cc Donna 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc I'm Mandy 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Wall Street Shuffle 10cc Don't Turn Me Away 10cc Feel The Love 10cc Food For Thought 10cc Good Morning Judge 10cc Life Is A Minestrone 10cc One Two Five 10cc People In Love 10cc Silly Love 10cc Woman In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 2 Unlimited No Limit 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 2nd Baptist Church (Lauren James Camey) Rise Up 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

Laughing with Kafka After Promethean Shame

PROBLEMI INTERNATIONAL,Laughing with vol. Kafka 2, no. 2,after 2018 Promethean © Society for Shame Theoretical Psychoanalysis Laughing with Kafka after Promethean Shame Jean-Michel Rabaté We have learned that Kafka’s main works deploy a fully-fledged political critique whose main weapon is derision.1 This use of laughter to satirize totalitarian regimes has been analyzed under the name of the “political grotesque” by Joseph Vogl. Here is what Vogl writes: From the terror of secret scenes of torture to childish officials, from the filth of the bureaucratic order to atavistic rituals of power runs a track of comedy that forever indicates the absence of reason, the element of the arbitrary in the execution of power and rule. How- ever, the element of the grotesque does not unmask and merely denounce. Rather it refers—as Foucault once pointed out—to the inevitability, the inescapability of precisely the grotesque, ridicu- lous, loony, or abject sides of power. Kafka’s “political grotesque” displays an unsystematic arbitrariness, which belongs to the func- tions of the apparatus itself. […] Kafka’s comedy turns against a diagnosis that conceives of the modernization of political power as 1 This essay is a condensed version of the second part of Kafka L.O.L., forthcoming from Quodlibet in 2018. In the first part, I address laughter in Kaf- ka’s works, showing that it takes its roots in the culture of a “comic grotesque” dominant in Expressionist German culture. Günther Anders’s groundbreaking book on Kafka then highlights the political dimensions of the work while criti- cizing Kafka’s Promethean nihilism. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

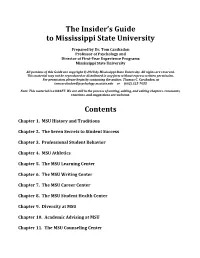

The Insider's Guide to Mississippi State University Contents

The Insider’s Guide to Mississippi State University Prepared by Dr. Tom Carskadon Professor of Psychology and Director of First-Year Experience Programs Mississippi State University All portions of this Guide are copyright © 2018 by Mississippi State University. All rights are reserved. This material may not be reproduced or distributed in any form without express written permission. For permission, please begin by contacting the author, Thomas G. Carskadon, at [email protected] or (662) 325-7655 Note: This material is a DRAFT. We are still in the process of writing, adding, and editing chapters. Comments, reactions, and suggestions are welcome. Contents Chapter 1. MSU History and Traditions Chapter 2. The Seven Secrets to Student Success Chapter 3. Professional Student Behavior Chapter 4. MSU Athletics Chapter 5. The MSU Learning Center Chapter 6. The MSU Writing Center Chapter 7. The MSU Career Center Chapter 8. The MSU Student Health Center Chapter 9. Diversity at MSU Chapter 10. Academic Advising at MSU Chapter 11. The MSU Counseling Center Chapter 1: THE PEOPLE’S UNIVERSITY poor, male or female, urban or rural, sophisticated or simple, black or white or red or yellow or brown, all Scholars, it’s a long story, but I actually came to are welcomed and given opportunity here. There is no Mississippi State by accident—and I loved it so much I “one” way that students are supposed to be at never left. Being a professor here is my first, last, and Mississippi State. This is the friendliest campus I have only full-time job. In fact, I was shocked to discover ever set foot on, and that is nothing new. -

![ONE NIGHT @ the CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset By: Arun K Gupta]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7467/one-night-the-call-center-chetan-bhagat-typeset-by-arun-k-gupta-1187467.webp)

ONE NIGHT @ the CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset By: Arun K Gupta]

ONE NIGHT @ THE CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset by: Arun K Gupta] This is someway my story. A great fun, inspirational One! Before you begin this book, I have a small request. Right here, note down three things. Write down something that i) you fear, ii) makes you angry and iii) you don’t like about yourself. Be honest, and write something that is meaningful to you. Do not think too much about why I am asking you to do this. Just do it. One thing I fear: __________________________________ One thing that makes me angry: __________________________________ One thing I do not like about myself: __________________________________ Okay, now forget about this exercise and enjoy the story. Have you done it? If not, please do. It will enrich your experience of reading this book. If yes, thanks Sorry for doubting you. Please forget about the exercise, my doubting you and enjoy the story. PROLOGUE _____________ The night train ride from Kanpur to Delhi was the most memorable journey of my life. For one, it gave me my second book. And two, it is not every day you sit in an empty compartment and a young, pretty girl walks in. Yes, you see it in the movies, you hear about it from friend’s friend but it never happens to you. When I was younger, I used to look at the reservation chart stuck outside my train bogie to check out all the female passengers near my seat (F-17 to F-25)is what I’d look for most). Yet, it never happened. -

D.C. "Truth" Written by John August

D.C. "Truth" written by John August FADE IN: 1 INT. TOWNHOUSE KITCHEN - MORNING 1 CLOSE ON the floor. We hear an approaching CLACK, CLACK, CLACK, CLACK. It’s LUCY, the biggest dog on television. From this angle, she looks like an AT-AT walker, lumbering but oddly graceful. She stops at her giant food bowl. It’s empty. This is a problem. 2 INT. UPSTAIRS TOWNHOUSE HALLWAY / BEDROOMS - DAY 2 WHIMPERING, Lucy scratches at doors, trying to wake someone up. At the third door, she succeeds in pushing it open. 3 INT. MASON’S ROOM - DAY 3 MASON SCOTT is sprawled out asleep, a lump amid a tangle of blankets. With no time for subtlety, Lucy climbs up on the bed, lying on top of him. She’s a big girl. Mason GROANS. MASON Alright, alright. I’ll get up. 4 INT. TOWNHOUSE / ENTRY - DAY 4 Coming in from outside, Mason lets Lucy off her leash. He has the Post under his arm. In the living room, an exhausted young woman (KRISTI) is looking for her other shoe. She’s sporting some serious bed- hair, and still wearing last night’s clothes. She finds the missing shoe under the coffee table. MASON Hello? Startled, she spins around to see Mason. She smiles, embarrassed. KRISTI Hi. 2. MASON Hi. (recognizing, smiles) Kristi, right? You work for Piedmont. KRISTI I do. (recognizing) You work for Abbott. MASON I did. I’m looking for a new job. (beat) Mason. He reaches out a hand to shake. She has to switch her shoe- holding hands to do so. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1990S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1990s Page 174 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1990 A Little Time Fantasy I Can’t Stand It The Beautiful South Black Box Twenty4Seven featuring Captain Hollywood All I Wanna Do is Fascinating Rhythm Make Love To You Bass-O-Matic I Don’t Know Anybody Else Heart Black Box Fog On The Tyne (Revisited) All Together Now Gazza & Lindisfarne I Still Haven’t Found The Farm What I’m Looking For Four Bacharach The Chimes Better The Devil And David Songs (EP) You Know Deacon Blue I Wish It Would Rain Down Kylie Minogue Phil Collins Get A Life Birdhouse In Your Soul Soul II Soul I’ll Be Loving You (Forever) They Might Be Giants New Kids On The Block Get Up (Before Black Velvet The Night Is Over) I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight Alannah Myles Technotronic featuring Robert Palmer & UB40 Ya Kid K Blue Savannah I’m Free Erasure Ghetto Heaven Soup Dragons The Family Stand featuring Junior Reid Blue Velvet Bobby Vinton Got To Get I’m Your Baby Tonight Rob ‘N’ Raz featuring Leila K Whitney Houston Close To You Maxi Priest Got To Have Your Love I’ve Been Thinking Mantronix featuring About You Could Have Told You So Wondress Londonbeat Halo James Groove Is In The Heart / Ice Ice Baby Cover Girl What Is Love Vanilla Ice New Kids On The Block Deee-Lite Infinity (1990’s Time Dirty Cash Groovy Train For The Guru) The Adventures Of Stevie V The Farm Guru Josh Do They Know Hangin’ Tough It Must Have Been Love It’s Christmas? New Kids On The Block Roxette Band Aid II Hanky Panky Itsy Bitsy Teeny Doin’ The Do Madonna Weeny Yellow Polka Betty Boo -

Prof. Michael G. Levine Fall 2015 172 College Avenue 01:470:388:01 Office Hours: Tuesdays, 4:30-6Pm 01:195:395:01 Tel

Prof. Michael G. Levine Fall 2015 172 College Avenue 01:470:388:01 Office Hours: Tuesdays, 4:30-6pm 01:195:395:01 Tel. 732-932-7201 Hardenbergh Hall B2 (T) [email protected] Hardenbergh Hall A4 (TH) TTh5 2:30-4:10 Love Letters Course Description: An examination of the intimacies, estrangements, enigmas and vagaries of love through the correspondence of a number of famous men and women of letters. Our exploration of the epistolary genre will range between private letters and published literary works and seek to read the one in conjunction with the other. Of particular concern will be structures of direct and indirect address, the use of pet names and invention of secret codes and idioms, the materiality of the letter and the postal network, epistolary conventions, and the ties through which poetry, philosophy, literature, personal and public correspondence are themselves intimately bound. Readings include selections from the letters of Friedrich Hölderlin and Susette Gontard (Diotima), Franz Kafka and Felice Bauer, Paul Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann, Walter Benjamin and Gretel Karplus Adorno. We will also read epistolary novels, poetry, criticism, and philosophical works by Goethe, Hölderlin, Celan, Bachmann, Barthes, Derrida, Siegert, and Benjamin. Discussion in English; all readings available in English translation and also in the original German or French whenever relevant. Books to be purchased at Rutgers University Bookstore Gateway Transit Bldg - 100 Somerset Street: Goethe, The Sorrows of Young Werther ISBN 978-0-19-958302-7 Correspondence (Seagull Books) by Celan, Paul, Bachman, Ingeborg 2010 Correspondence Walter Benjamin and Gretel Adorno ISBN 13: 978074569023 Derrida, The Post Card, ISBN 13: 978-0226143224 Canetti, Kafka’s Other Trial 0-8052-0705-8 Sakai https://sakai.rutgers.edu/portal/site/7ecf7c27-beb7-4696-9844-faed103a2ec9 All other readings available on course website on Sakai When accessing this material it is necessary to use your RU Eden account address. -

November/December 2012

From the Office By Daniel D. Skwire His complaints about his duties were epic, but Kafka clearly drew satisfaction from working his day job at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute of the Kingdom of Bohemia in Prague. ITTLE KNOWN DURING HIS LIFETIME, ghastly machine to torture and execute his prisoners. And in Franz Kafka has come to be recognized as one of The Trial, a man must defend himself in court without being the greatest writers of the 20th century. His works informed of the crime he has been accused of committing. These include some of the most disturbing and enduring portraits of disillusionment, anxiety, and despair anticipate the images of modern fiction. The hero of The Metamor- subsequent horrors of mid-20th-century war and inhumanity. phosis, for example, awakens one morning to find he has been Many of the details of Kafka’s own life are scarcely more Ltransformed into a giant insect. Kafka’s short story “In the Penal cheerful. A sickly individual, he struggled with tuberculosis and Colony” features an officer in a prison camp who maintains a other illnesses before dying at the age of 40. His relationships 20 CONTINGENCIES NOV | DEC.12 WWW.CONTINGENCIES.ORG of Franz Kafka Kafka's desk at the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute in Prague with women were unsuccessful, and he never married despite their occupations. An examination of Kafka’s insurance career being engaged on several occasions. He lived with his parents humanizes him and sheds light on his writing by showing his for most of his life and complained bitterly that his work in the dedication, accomplishments, and sense of humor alongside his insurance profession kept him from his true calling of writing—a many frustrations. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co.