Explosion and the Normativity of Logic 1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classifying Material Implications Over Minimal Logic

Classifying Material Implications over Minimal Logic Hannes Diener and Maarten McKubre-Jordens March 28, 2018 Abstract The so-called paradoxes of material implication have motivated the development of many non- classical logics over the years [2–5, 11]. In this note, we investigate some of these paradoxes and classify them, over minimal logic. We provide proofs of equivalence and semantic models separating the paradoxes where appropriate. A number of equivalent groups arise, all of which collapse with unrestricted use of double negation elimination. Interestingly, the principle ex falso quodlibet, and several weaker principles, turn out to be distinguishable, giving perhaps supporting motivation for adopting minimal logic as the ambient logic for reasoning in the possible presence of inconsistency. Keywords: reverse mathematics; minimal logic; ex falso quodlibet; implication; paraconsistent logic; Peirce’s principle. 1 Introduction The project of constructive reverse mathematics [6] has given rise to a wide literature where various the- orems of mathematics and principles of logic have been classified over intuitionistic logic. What is less well-known is that the subtle difference that arises when the principle of explosion, ex falso quodlibet, is dropped from intuitionistic logic (thus giving (Johansson’s) minimal logic) enables the distinction of many more principles. The focus of the present paper are a range of principles known collectively (but not exhaustively) as the paradoxes of material implication; paradoxes because they illustrate that the usual interpretation of formal statements of the form “. → . .” as informal statements of the form “if. then. ” produces counter-intuitive results. Some of these principles were hinted at in [9]. Here we present a carefully worked-out chart, classifying a number of such principles over minimal logic. -

On Basic Probability Logic Inequalities †

mathematics Article On Basic Probability Logic Inequalities † Marija Boriˇci´cJoksimovi´c Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Belgrade, Jove Ili´ca154, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] † The conclusions given in this paper were partially presented at the European Summer Meetings of the Association for Symbolic Logic, Logic Colloquium 2012, held in Manchester on 12–18 July 2012. Abstract: We give some simple examples of applying some of the well-known elementary probability theory inequalities and properties in the field of logical argumentation. A probabilistic version of the hypothetical syllogism inference rule is as follows: if propositions A, B, C, A ! B, and B ! C have probabilities a, b, c, r, and s, respectively, then for probability p of A ! C, we have f (a, b, c, r, s) ≤ p ≤ g(a, b, c, r, s), for some functions f and g of given parameters. In this paper, after a short overview of known rules related to conjunction and disjunction, we proposed some probabilized forms of the hypothetical syllogism inference rule, with the best possible bounds for the probability of conclusion, covering simultaneously the probabilistic versions of both modus ponens and modus tollens rules, as already considered by Suppes, Hailperin, and Wagner. Keywords: inequality; probability logic; inference rule MSC: 03B48; 03B05; 60E15; 26D20; 60A05 1. Introduction The main part of probabilization of logical inference rules is defining the correspond- Citation: Boriˇci´cJoksimovi´c,M. On ing best possible bounds for probabilities of propositions. Some of them, connected with Basic Probability Logic Inequalities. conjunction and disjunction, can be obtained immediately from the well-known Boole’s Mathematics 2021, 9, 1409. -

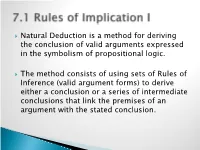

7.1 Rules of Implication I

Natural Deduction is a method for deriving the conclusion of valid arguments expressed in the symbolism of propositional logic. The method consists of using sets of Rules of Inference (valid argument forms) to derive either a conclusion or a series of intermediate conclusions that link the premises of an argument with the stated conclusion. The First Four Rules of Inference: ◦ Modus Ponens (MP): p q p q ◦ Modus Tollens (MT): p q ~q ~p ◦ Pure Hypothetical Syllogism (HS): p q q r p r ◦ Disjunctive Syllogism (DS): p v q ~p q Common strategies for constructing a proof involving the first four rules: ◦ Always begin by attempting to find the conclusion in the premises. If the conclusion is not present in its entirely in the premises, look at the main operator of the conclusion. This will provide a clue as to how the conclusion should be derived. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in the consequent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via modus ponens. ◦ If the conclusion contains a negated letter and that letter appears in the antecedent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining the negated letter via modus tollens. ◦ If the conclusion is a conditional statement, consider obtaining it via pure hypothetical syllogism. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a disjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via disjunctive syllogism. Four Additional Rules of Inference: ◦ Constructive Dilemma (CD): (p q) • (r s) p v r q v s ◦ Simplification (Simp): p • q p ◦ Conjunction (Conj): p q p • q ◦ Addition (Add): p p v q Common Misapplications Common strategies involving the additional rules of inference: ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a conjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via simplification. -

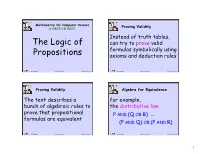

Propositional Logic (PDF)

Mathematics for Computer Science Proving Validity 6.042J/18.062J Instead of truth tables, The Logic of can try to prove valid formulas symbolically using Propositions axioms and deduction rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.1 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.2 Proving Validity Algebra for Equivalence The text describes a for example, bunch of algebraic rules to the distributive law prove that propositional P AND (Q OR R) ≡ formulas are equivalent (P AND Q) OR (P AND R) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.3 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.4 1 Algebra for Equivalence Algebra for Equivalence for example, The set of rules for ≡ in DeMorgan’s law the text are complete: ≡ NOT(P AND Q) ≡ if two formulas are , these rules can prove it. NOT(P) OR NOT(Q) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.5 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.6 A Proof System A Proof System Another approach is to Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a start with some valid particularly elegant example of this idea. formulas (axioms) and deduce more valid formulas using proof rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.7 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.8 2 A Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a Axioms: particularly elegant example of 1) (¬P → P) → P this idea. It covers formulas 2) P → (¬P → Q) whose only logical operators are 3) (P → Q) → ((Q → R) → (P → R)) IMPLIES (→) and NOT. The only rule: modus ponens Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.9 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.10 Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Prove formulas by starting with Prove formulas by starting with axioms and repeatedly applying axioms and repeatedly applying the inference rule. -

Deontic Logic and Meta-Ethics

Deontic Logic and Meta-Ethics • Deontic Logic as been a field in which quite apart from the questions of antinomies "paradoxes" have played a decisive roles, since the field has been invented. These paradoxes (like Ross' Paradox or the Good Samaritian) are said to show that some intuitively valid logical principles cannot be true in deontic logic, even if the same principles (like deductive closure within a modality) are valid in alethic modal logic. Paraconsistency is not concerned with solutions to these paradoxes. pp ∧¬∧¬pp • There are, however, lots of problems with ex contradictione qoudlibet Manuel Bremer in deontic logic, since systems of norms and regulations, even more so Centre for Logic, Language and if they are historically grown, have a tendency to contain conflicting Information requirements. To restrict the ensuing problems at least a weak paraconsistent logic is needed. • There may be, further on, real antinomies of deontic logic and meta- ethics (understood comprehensively as including also some basic decision and game theory). Inconsistent Obligations • It often may happen that one is confronted with inconsistent obligations. • Consider for example the rule that term papers have to be handed in at the institute's office one week before the session in question combined with the rule that one must not disturb the secretary at the institute's office if she is preparing an institute meeting. What if the date of handing in your paper falls on a day when an institute meeting is pp ∧¬∧¬pp prepared? Entering the office is now obligatory (i.e. it is obligatory that it is the Manuel Bremer case that N.N. -

Chapter 9: Answers and Comments Step 1 Exercises 1. Simplification. 2. Absorption. 3. See Textbook. 4. Modus Tollens. 5. Modus P

Chapter 9: Answers and Comments Step 1 Exercises 1. Simplification. 2. Absorption. 3. See textbook. 4. Modus Tollens. 5. Modus Ponens. 6. Simplification. 7. X -- A very common student mistake; can't use Simplification unless the major con- nective of the premise is a conjunction. 8. Disjunctive Syllogism. 9. X -- Fallacy of Denying the Antecedent. 10. X 11. Constructive Dilemma. 12. See textbook. 13. Hypothetical Syllogism. 14. Hypothetical Syllogism. 15. Conjunction. 16. See textbook. 17. Addition. 18. Modus Ponens. 19. X -- Fallacy of Affirming the Consequent. 20. Disjunctive Syllogism. 21. X -- not HS, the (D v G) does not match (D v C). This is deliberate to make sure you don't just focus on generalities, and make sure the entire form fits. 22. Constructive Dilemma. 23. See textbook. 24. Simplification. 25. Modus Ponens. 26. Modus Tollens. 27. See textbook. 28. Disjunctive Syllogism. 29. Modus Ponens. 30. Disjunctive Syllogism. Step 2 Exercises #1 1 Z A 2. (Z v B) C / Z C 3. Z (1)Simp. 4. Z v B (3) Add. 5. C (2)(4)MP 6. Z C (3)(5) Conj. For line 4 it is easy to get locked into line 2 and strategy 1. But they do not work. #2 1. K (B v I) 2. K 3. ~B 4. I (~T N) 5. N T / ~N 6. B v I (1)(2) MP 7. I (6)(3) DS 8. ~T N (4)(7) MP 9. ~T (8) Simp. 10. ~N (5)(9) MT #3 See textbook. #4 1. H I 2. I J 3. -

Argument Forms and Fallacies

6.6 Common Argument Forms and Fallacies 1. Common Valid Argument Forms: In the previous section (6.4), we learned how to determine whether or not an argument is valid using truth tables. There are certain forms of valid and invalid argument that are extremely common. If we memorize some of these common argument forms, it will save us time because we will be able to immediately recognize whether or not certain arguments are valid or invalid without having to draw out a truth table. Let’s begin: 1. Disjunctive Syllogism: The following argument is valid: “The coin is either in my right hand or my left hand. It’s not in my right hand. So, it must be in my left hand.” Let “R”=”The coin is in my right hand” and let “L”=”The coin is in my left hand”. The argument in symbolic form is this: R ˅ L ~R __________________________________________________ L Any argument with the form just stated is valid. This form of argument is called a disjunctive syllogism. Basically, the argument gives you two options and says that, since one option is FALSE, the other option must be TRUE. 2. Pure Hypothetical Syllogism: The following argument is valid: “If you hit the ball in on this turn, you’ll get a hole in one; and if you get a hole in one you’ll win the game. So, if you hit the ball in on this turn, you’ll win the game.” Let “B”=”You hit the ball in on this turn”, “H”=”You get a hole in one”, and “W”=”you win the game”. -

CHAPTER 8 Hilbert Proof Systems, Formal Proofs, Deduction Theorem

CHAPTER 8 Hilbert Proof Systems, Formal Proofs, Deduction Theorem The Hilbert proof systems are systems based on a language with implication and contain a Modus Ponens rule as a rule of inference. They are usually called Hilbert style formalizations. We will call them here Hilbert style proof systems, or Hilbert systems, for short. Modus Ponens is probably the oldest of all known rules of inference as it was already known to the Stoics (3rd century B.C.). It is also considered as the most "natural" to our intuitive thinking and the proof systems containing it as the inference rule play a special role in logic. The Hilbert proof systems put major emphasis on logical axioms, keeping the rules of inference to minimum, often in propositional case, admitting only Modus Ponens, as the sole inference rule. 1 Hilbert System H1 Hilbert proof system H1 is a simple proof system based on a language with implication as the only connective, with two axioms (axiom schemas) which characterize the implication, and with Modus Ponens as a sole rule of inference. We de¯ne H1 as follows. H1 = ( Lf)g; F fA1;A2g MP ) (1) where A1;A2 are axioms of the system, MP is its rule of inference, called Modus Ponens, de¯ned as follows: A1 (A ) (B ) A)); A2 ((A ) (B ) C)) ) ((A ) B) ) (A ) C))); MP A ;(A ) B) (MP ) ; B 1 and A; B; C are any formulas of the propositional language Lf)g. Finding formal proofs in this system requires some ingenuity. Let's construct, as an example, the formal proof of such a simple formula as A ) A. -

Proposi'onal Logic Proofs Proof Method #1: Truth Table Example

9/9/14 Proposi'onal Logic Proofs • An argument is a sequence of proposi'ons: Inference Rules ² Premises (Axioms) are the first n proposi'ons (Rosen, Section 1.5) ² Conclusion is the final proposi'on. p p ... p q TOPICS • An argument is valid if is a ( 1 ∧ 2 ∧ ∧ n ) → tautology, given that pi are the premises • Logic Proofs (axioms) and q is the conclusion. ² via Truth Tables € ² via Inference Rules 2 Proof Method #1: Truth Table Example Proof By Truth Table s = ((p v q) ∧ (¬p v r)) → (q v r) n If the conclusion is true in the truth table whenever the premises are true, it is p q r ¬p p v q ¬p v r q v r (p v q)∧ (¬p v r) s proved 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 n Warning: when the premises are false, the 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 conclusion my be true or false 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 n Problem: given n propositions, the truth 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 n table has 2 rows 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 n Proof by truth table quickly becomes 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 infeasible 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 3 4 1 9/9/14 Proof Method #2: Rules of Inference Inference proper'es n A rule of inference is a pre-proved relaon: n Inference rules are truth preserving any 'me the leJ hand side (LHS) is true, the n If the LHS is true, so is the RHS right hand side (RHS) is also true. -

A New Probabilistic Explanation of the Modus Ponens–Modus Tollens Asymmetry

A New Probabilistic Explanation of the Modus Ponens–Modus Tollens Asymmetry Benjamin Eva ([email protected]) Department of Philosophy, Univeristy of Konstanz, 78464 Konstanz (Germany) Stephan Hartmann ([email protected]) Munich Center for Mathematical Philosophy, LMU Munich, 80539 Munich (Germany) Henrik Singmann ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL (UK) Abstract invalid inferences (i.e., they accept more valid than invalid inferences). However, their behavior is clearly not in line A consistent finding in research on conditional reasoning is that individuals are more likely to endorse the valid modus po- with the norms of classical logic. Whereas participants tend nens (MP) inference than the equally valid modus tollens (MT) to unanimously accept the valid MP, the acceptance rates for inference. This pattern holds for both abstract task and prob- the equally valid MT inference scheme is considerably lower. abilistic task. The existing explanation for this phenomenon within a Bayesian framework (e.g., Oaksford & Chater, 2008) In a meta-analysis of the abstract task, Schroyens, Schaeken, accounts for this asymmetry by assuming separate probabil- and d’Ydewalle (2001) found acceptance rates of .97 for MP ity distributions for both MP and MT. We propose a novel compared to acceptance rates of .74 for MT. This MP-MT explanation within a computational-level Bayesian account of 1 reasoning according to which “argumentation is learning”. asymmetry will be the main focus of -

Modus Ponens and the Logic of Dominance Reasoning 1 Introduction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PhilPapers Modus Ponens and the Logic of Dominance Reasoning Nate Charlow Abstract If modus ponens is valid, you should take up smoking. 1 Introduction Some recent work has challenged two principles thought to govern the logic of the in- dicative conditional: modus ponens (Kolodny & MacFarlane 2010) and modus tollens (Yalcin 2012). There is a fairly broad consensus in the literature that Kolodny and Mac- Farlane’s challenge can be avoided, if the notion of logical consequence is understood aright (Willer 2012; Yalcin 2012; Bledin 2014). The viability of Yalcin’s counterexam- ple to modus tollens has meanwhile been challenged on the grounds that it fails to take proper account of context-sensitivity (Stojnić forthcoming). This paper describes a new counterexample to modus ponens, and shows that strate- gies developed for handling extant challenges to modus ponens and modus tollens fail for it. It diagnoses the apparent source of the counterexample: there are bona fide in- stances of modus ponens that fail to represent deductively reasonable modes of reasoning. The diagnosis might seem trivial—what else, after all, could a counterexample to modus ponens consist in?1—but, appropriately understood, it suggests something like a method for generating a family of counterexamples to modus ponens. We observe that a family of uncertainty-reducing “Dominance” principles must implicitly forbid deducing a conclusion (that would otherwise be sanctioned by modus ponens) when certain con- ditions on a background object (e.g., a background decision problem or representation of relevant information) are not met. -

Gert-Jan C. LOKHORST an ALTERNATIVE INTUITIONISTIC

REPORTS ON MATHEMATICAL LOGIC 51 (2016), 35–41 doi:10.4467/20842589RM.16.003.5280 Gert-Jan C. LOKHORST AN ALTERNATIVE INTUITIONISTIC VERSION OF MALLY’S DEONTIC LOGIC A b s t r a c t. Some years ago, Lokhorst proposed an intuitionistic reformulation of Mally’s deontic logic (1926). This reformulation was unsatisfactory, because it provided a striking theorem that Mally himself did not mention. In this paper, we present an alter- native reformulation of Mally’s deontic logic that does not provide this theorem. .1 Introduction Some years ago, Lokhorst proposed an intuitionistic reformulation of Mally’s deontic logic (1926) [3]. This reformulation was unsatisfactory, because it provided a striking theorem that Mally himself did not mention, namely ⌥(A A). In this paper, we present an alternative reformulation of Mally’s _¬ deontic logic that does not provide this theorem. Received 4 October 2015 Keywords and phrases: deontic logic, intuitionistic logic. 36 GERT-JAN C. LOKHORST .2 Definitions Heyting’s system of intuitionistic propositional logic h is defined as follows [1, Ch. 2]. Axioms: (a) A (B A). ! ! (b) (A (B C)) ((A B) (A C)). ! ! ! ! ! ! (c) (A B) A;(A B) B. ^ ! ^ ! (d) A (B (A B)). ! ! ^ (e) A (A B); B (A B). ! _ ! _ (f) (A C) ((B C) ((A B) C)). ! ! ! ! _ ! (g) A. ?! Rule: A, A B/B (modus ponens, MP). ! Definitions: A = A , = , A B =(A B) (B A). ¬ !? > ¬? $ ! ^ ! The second-order intuitionistic propositional calculus with comprehension C2h is h plus [1, Ch. 9]: Axioms: Q1 ( x)A(x) A(y). 8 ! Q2 A(y) ( x)A(x).