Dyslexia: an Overview*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebook Download Teaching Literacy to Learners With

TEACHING LITERACY TO LEARNERS WITH DYSLEXIA: A MULTI-SENSORY APPROACH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kathleen S. Kelly, Sylvia Phillips | 424 pages | 14 Oct 2011 | Sage Publications Ltd | 9780857025357 | English | London, United Kingdom Teaching Literacy to Learners with Dyslexia: A Multi-sensory Approach PDF Book Key Takeaways Orton—Gillingham is a well-regarded approach to teaching kids who struggle with reading. With tried and tested strategies and activities this book continues to provide everything you need to help improve and develop the literacy skills of learners in your setting including;. Immediate online access to all issues from This creative kind of teaching doesn't have to be that unorthodox, since counting on your fingers is multisensory, but it definitely goes beyond the traditional approach to education that relies almost exclusively on vision reading text and hearing listening to the teacher talk. Teachers should demonstrate and model appropriate learning strategies for all their pupils. Teaching the confusing letter B from Sight and Sound Reading! Affective behaviours include personality variables such as persistence and perseverance, frustration and tolerance, curiosity, locus of control, achievement motivation, risk taking, cautiousness, competition, co-operation, reaction to reinforcement and personal interests. Quick Facts about Multisensory Learning. Have you ever danced in mathematics, sung a song in science or painted in phys. The development of word reading skills and reading comprehension skills can be facilitated by morphological awareness. Buy the book. Dyscalculia Learning Support Formative Assessment. It is an acquired ability that requires effort and incremental skill development. Dyslexic author and champion Ben Foss is fond of distinguishing "eye reading" from "ear reading" which we think is a great idea, because your can indeed read with your ears using audiobooks and text to speech applications. -

Sampling Inner Experience in the Learning Disabled Population

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1992 Sampling inner experience in the learning disabled population Barbara Lynn Schamanek University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Schamanek, Barbara Lynn, "Sampling inner experience in the learning disabled population" (1992). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 187. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/sa8u-f0vh This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Dyslexia and Physical Education (Outdoor Education, Sports, Games, Dance)

Dyslexia and Physical Education (Outdoor Education, Sports, Games, Dance) No 2.9 in the series of Supporting Dyslexic Pupils in the Secondary Curriculum By Moira Thomson Supporting Dyslexic Pupils in the Secondary Curriculum by Moira Thomson DYSLEXIA AND PHYSICAL EDUCATION (Outdoor Education, Sports, Games, Dance) Published in Great Britain by Dyslexia Scotland in 2007 Dyslexia Scotland, Stirling Business Centre Wellgreen, Stirling FK8 2DZ Charity No: SCO00951 © Dyslexia Scotland 2007 ISBN 13 978 1 906401 15 3 Printed and bound in Great Britain by M & A Thomson Litho Ltd, East Kilbride, Scotland Supporting Dyslexic Pupils in the Secondary Curriculum by Moira Thomson Complete set comprises 18 booklets and a CD of downloadable material (see inside back cover for full details of CD contents) Foreword by Dr. Gavin Reid, a senior lecturer in the Department of Educational Studies, Moray House School of Education, University of Edinburgh. An experienced teacher, educational psychologist, university lecturer, researcher and author, he has made over 600 conference and seminar presentations in more than 35 countries and has authored, co-authored and edited fifteen books for teachers and parents. 1.0 Dyslexia: Secondary Teachers’ Guides 1.1. Identification and Assessment of Dyslexia at Secondary School 1.2. Dyslexia and the Underpinning Skills for the Secondary Curriculum 1.3. Classroom Management of Dyslexia at Secondary School 1.4. Information for the Secondary Support for Learning Team 1.5. Supporting Parents of Secondary School Pupils with Dyslexia 1.6. Using ICT to Support Dyslexic Pupils in the Secondary Curriculum 1.7. Dyslexia and Examinations 2.0 Subject Teachers’ Guides 2.1. -

The Essential Need for Ortin-Gillingham Based Reading

“So please, oh please, we beg, we pray. Go throw your TV set away. And in its place you can install. A lovely bookshelf on the wall.” Roald Dahl WHO WAS DR. SAMUEL ORTON? (1879-1948) 1. A neuropsychiatrist and pathologist who worked with stroke victims in Iowa. 2. Revolutionized thought on reading failure and language based processing difficulties while working with stroke patients that had lost the ability to read. 3. Hypothesized that students with reading difficulties were not due to brain damage. Cont. ORTON CONT. 4. Maintained disabilities and disorders were neurological and not environmental. 5. Influenced by kinesthetic method described by Grace Fernald and Helen Keller. 6. Using neuroscientific information and best practices in remediation techniques, he formulated a set of teaching principles and practices. Dunson, W. What is the Orton-Gillingham Approach? Retrieved from http://www.special educationdvisor.com/what-is-orton-gillingham-approach/ The Orton-Gillingham Approach in Practice. Retrieved from http://archive.excellence gateway.org.uk/article.aspx?o=126837 WHO WAS ANNA GILLINGHAM?1878-1963 Remedial teacher, administrator, psychologist, teacher trainer • Worked with Dr. Orton at the Neurological Institute, Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, NY. • Combined Orton’s teaching philosophy/methodology with structure of English/American Language. (Excellence Gateway). • Devised methods of teaching based on formulated principles of Dr. Orton. • Wrote: Orton-Gillingham Manual: Remedial Training for Children with Specific Disability in Reading, Spelling, and Handwriting. Duchan, J. Retrieved from http://www.acsubuffalo.edu/~duchan/indew.html records.ancestry.com NAEP NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF EDUCATIONAL PROGRESS 1998 • 2 million children receive special education for reading. -

White Paper: Dyslexia and Read Naturally 1 Table of Contents Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc

Dyslexia and Read Naturally Cory Stai Director of Research and Partnership Development Read Naturally, Inc. Published by: Read Naturally, Inc. Saint Paul, Minnesota Phone: 800.788.4085/651.452.4085 Website: www.readnaturally.com Email: [email protected] Author: Cory Stai, M.Ed. Illustration: “A Modern Vision of the Cortical Networks for Reading” from Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read by Stanislas Dehaene, copyright © 2009 by Stanislas Dehaene. Used by permission of Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Part I: What Is Dyslexia? . 3 Part II: How Do Proficient Readers Read Words? . 9 Part III: How Does Dyslexia Affect Typical Reading? . .. 15 Part IV: Dyslexia and Read Naturally Programs . 18 End Notes . 24 References . 28 Appendix A: Further Reading . 35 Appendix B: Program Scope and Sequence Summaries . 36 White Paper: Dyslexia and Read Naturally 1 Table of Contents Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc. Table of Contents 2 White Paper: Dyslexia and Read Naturally Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc. Read Naturally’s mission is to facilitate the learning necessary for every child to become a confident, proficient reader . Dyslexia is a reading disability that impacts millions of Americans . To support learners with dyslexia, educators must understand: n what dyslexia is and what it is not n how the dyslexic brain differs from that of a typical reader n how and why recommended reading interventions help To these ends, this paper supports educators to deepen their understanding of the instructional needs of dyslexic readers and to confidently select and use Read Naturally intervention programs, as appropriate . -

Investigating the Applicability of the Neurodevelopmental Framework to Enhance Learning for All Students, Especially Those with Mild to Moderate Disabilites

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2012 Investigating the applicability of the neurodevelopmental framework to enhance learning for all students, especially those with mild to moderate disabilites Lisa B. Kline California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Kline, Lisa B., "Investigating the applicability of the neurodevelopmental framework to enhance learning for all students, especially those with mild to moderate disabilites" (2012). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 421. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/421 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVESTIGATING THE APPLICABILITY OF THE NEURODEVELOPMENTAL FRAMEWORK TO ENHANCE LEARNING FOR ALL STUDENTS, ESPECIALLY THOSE WITH MILD TO MODERATE DISABILTIES By Lisa B. Kline A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in Education The College of Professional Studies School of Education California State University, Monterey Bay December 2012 ©2012 Lisa B. Kline. All Rights Reserved. 11 Action Thesis Signature Page INVESTIGATING THE APPLICABILITY OF THE NEURODEVELOPMENTAL FRAMEWORK TO ENHANCE LEARNING FOR ALL STUDENTS, ESPECIALLY THOSE WITH MILD TO MODERATE DISABILTIES By LISA B. KLINE APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: iii Acknowledgements A sincere thank you to Dr. -

IDA Dyslexia Handbook: What Every Family Should Know

IDA Dyslexia Handbook: What Every Family Should Know Introduction 1 Chapter 1: IDA Definition of Dyslexia 2 Chapter 2: Characteristics of Dyslexia 3 Chapter 3: Valid Assessments for Dyslexia 9 Chapter 4: Identifying Effective Teaching Approaches - Structured Literacy 15 Chapter 5: Managing the Education of a Student with Dyslexia 19 Chapter 6: Transitioning into College 22 Chapter 7: Recommended Readings and Resources on Dyslexia 28 Chapter 8: Glossary of Terms 31 References 33 © Copyright 2014, The International Dyslexia Association (IDA). IDA encourages the reproduction and distribution of this handbook. If portions of the text are cited, appropriate reference must be made. This may not be reprinted for the purpose of resale. 40 York Road, 4th Floor • Baltimore, MD 21204 [email protected] www.interdys.org Introduction Welcome to the International Dyslexia Association (IDA). IDA was founded in 1949 in memory of Dr. Samuel Orton, a pioneer in the field of dyslexia. IDA’s mission is to actively promote effective teaching approaches and intervention strategies for persons with dyslexia and related disorders. IDA encourages and supports interdisciplinary reading research and disseminates this information to professionals and the general public. IDA has 42 state branches and 22 global partners to carry out its mission. These states and countries provide information regarding the best methods for helping individuals who need to learn how to read. Structured Literacy describes the scientifically based approach for learning how to read. Chapter 4 addresses Structured Literacy and evidence-based approaches for learning to read. The IDA Handbook provides necessary information regarding: definition of dyslexia characteristics of dyslexia appropriate assessment tools evidence-based interventions, suggestions for managing a dyslexic’s educational process In addition, helpful resources and a glossary of terms are provided to better understand dyslexia and its related disorders. -

Download Samuel T. & June Lyday Orton Papers PDF Finding

Archives & Special Collections, Columbia University Health Sciences Library Samuel T. Orton and June Lyday Orton Papers ORTON, SAMUEL TORREY, 1879-1948. ORTON, JUNE LYDAY, 1898-1977. Samue l Torre y Orton and June Lyday Orton papers, 1901-1977. 12 cubic feet (29 document boxes, 6 card file boxes, 1 record storage box) BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE: The husband and wife team of Samuel Torrey Orton and June Lyday Orton were professional partners in the field of language disabilit ies. Together they conducted research, trained educators and therapists, and treated individuals with reading and writing difficulties. In the process, they became two of the most important individuals in the history of dyslexia. Samuel Torrey Orton was born in Columbus, Ohio, on October 15, 1879. His father, Edward Orton, was at various times the state geologist of Ohio, the President of Antioch College, and the first President of Ohio State University. Other distinguished family members included his cousin, President William Howard Taft, and his uncle, educator Horace Taft of the Taft School in Watertown, Connecticut, where young Sam completed high school in 1897. Orton attended Ohio State University (B.S., 1901), the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (M.D., 1905), and Harvard University (M.A., 1906). He was a member of Alpha Omega Alpha and Sigma Xi. He began his medical career by training in pathology under Frank B. Mallory at Boston City Hospital in 1905-06. He then spent a year at the Columbus (Ohio) State Hospital, and two years at St. Ann’s Hospital in Anaconda, Montana. On October 13, 1908, he married Mary Follett in Columbus, Ohio. -

Research Into Dyslexia Provision in Wales Literature Review on the State of Research for Children with Dyslexia

Research into dyslexia provision in Wales Literature review on the state of research for children with dyslexia Research Research document no: 058/2012 Date of issue: 24 August 2012 Research into dyslexia provision in Wales Audience Local authorities and schools. Overview The Welsh Government commissioned a literature review, auditing and benchmarking exercise to respond to the recommendations of the former Enterprise and Learning Committee’s Follow-up report on Support for People with Dyslexia in Wales (2009). This work was conducted by a working group, which comprised of experts in the field of specific learning difficulties (SpLD) in Wales including the Centre for Child Development at Swansea University, the Miles Dyslexia Centre at Bangor University, the Dyscovery Centre at the University of Wales, Newport, the Wrexham NHS Trust and representatives from the National Association of Principal Educational Psychologists (NAPEP) and the Association of Directors of Education in Wales (ADEW). Action None – for information only. required Further Enquiries about this document should be directed to: information Additional Needs Branch Support for Learners Division Department for Education and Skills Welsh Government Cathays Park Cardiff CF10 3NQ Tel: 029 2082 6044 Fax: 029 2080 1044 e-mail: [email protected] Additional This document can be accessed from the Welsh Government’s copies website at http://wales.gov.uk/topics/educationandskills/publications/ researchandevaluation/research/?lang=en Related Current literacy and dyslexia provision in Wales: A report on the documents benchmarking study (2012) Digital ISBN 978 0 7504 7972 1 © Crown copyright 2012 WG16498 Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 I. INTRODUCTION 3 II. CURRENT DEFINITIONS OF DYSLEXIA 4 III. -

The Online Journal of Missouri Speech-Language-Hearing Association 2015

THE ONLINE JOURNAL OF MISSOURI SPEECH-LANGUAGE-HEARING ASSOCIATION 2015 The Online Journal of Missouri Speech- Language-Hearing Volume1; Number 1; 2015 Association © Missouri Speech-Language- Hearing Association 2015 Ray, Jayanti Annual Publication of the Missouri Speech- Language-Hearing Association Scope of OJMSHA The Online Journal of MSHA is a peer-reviewed interprofessional journal publishing articles that make clinical and research contributions to current practices in the fields of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology. The journal is also intended to provide updates on various professional issues faced by our members while bringing them the latest and most significant findings in the field of communication disorders. The journal welcomes academicians, clinicians, graduate and undergraduate students, and other allied health professionals who are interested or engaged in research in the field of communication disorders. The interested contributors are highly encouraged to submit their manuscripts/papers to [email protected]. An inquiry regarding specific information about a submission may be emailed to Jayanti Ray ([email protected]). Upon acceptance of the manuscripts, a PDF version of the journal will be posted online. Our first issue is expected to be published in August. This publication is open to both members and nonmembers. Readers can freely access or cite the article. 2 THE ONLINE JOURNAL OF MISSOURI SPEECH-LANGUAGE-HEARING ASSOCIATION 2015 The Online Journal of Missouri Speech-Language-Hearing Association Vol. 1 No. 1 ∙ August 2015 Table of Contents Story Presentation Effects on the Narratives of Preschool Children 8 From Low and Middle Socioeconomic Homes Grace E. McConnell Evidence-Based Practice, Assessment, and Intervention Approaches for 25 Children with Developmental Dyslexia Ryan Riggs Advocacy Training: Taking Charge of Your Future 37 Nancy Montgomery, Greg Turner, and Robert deJonge Working with Your Librarian 42 Cherri G. -

Differences. CM BEST COPY AVAILABLE

DOCUMENT RESUME ID 100 112 EC 070 982 MLR Project Child Ten Kit 3: Characteristicsof the Language Disabled Child. INSTITUTION Texas Education Agency, Austin. NOTE 51p.; For related information see EC 070975-992 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$3.15 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Behavioral Objectives; Exceptional Child Education; Instructional Materials; *Language Handicapped; Learning Disabilities; *Performance Based Teacher Education; Performance Criteria; *Student Characteristics IDENTIFIERS *Project CHILD ABSTRACT Presented is the third of 12 instructional kits, on characteristics of the language disabled (LD) child, for a performance based teacher education program which was developed by Project CHILD, a research effort to validate identification, intervention, and teacher education programs for LD children. Included in the kit are directions for preassessment tasks for the five performance objectives, a listing of the five performance objectives (such as correctly identifying three learning disabled children from five case histories), instructions for four learning experiences (such as using correct terminology to identify pantomimed behavior characteristics), a checklist for self-evaluation for each of the performance objectives, and guidelines for proficiency assessment of each objective. Also included are two descriptions of LD children intended to help the student identify individual differences. CM BEST COPY AVAILABLE PROJECT CHILD U.S. DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH, EDUCATION A WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN Ten Kit 3 ATOM IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY Texas Education Agency Austin, Texas 4 Texas Education Agency publications are not copyrighted. -

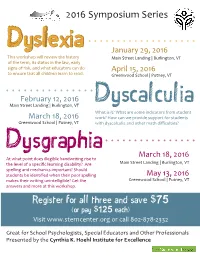

2016 Symposium Series

2016 Symposium Series Dyslexia January 29, 2016 This workshop will review the history Main Street Landing | Burlington, VT of the term, its status in the law, early signs of risk, and what educators can do April 15, 2016 to ensure that all children learn to read. Greenwood School | Putney, VT February 12, 2016 Dyscalculia Main Street Landing | Burlington, VT What is it? What are some indicators from student March 18, 2016 work? How can we provide support for students Greenwood School | Putney, VT with dyscalculia and other math difficulties? Dysgrap hia March 18, 2016 At what point does illegible handwriting rise to the level of a specific learning disability? Are Main Street Landing | Burlington, VT spelling and mechanics important? Should students be identified when their poor spelling May 13, 2016 makes their writing unintelligible? Get the Greenwood School | Putney, VT answers and more at this workshop. Register for all three and save $75 (or pay $125 each) Visit www.sterncenter.org or call 802-878-2332 Great for School Psychologists, Special Educators and Other Professionals Presented by the Cynthia K. Hoehl Institute for Excellence Friday, April 15, 2016 Dyslexia Greenwood School | Putney, Vermont The field of reading is rife with About the Presenter controversy. We not only disagree over Melissa Farrall, Ph.D. what constitutes a reading disorder, we is the author of Reading often bristle over the language that others Assessment: Linking Language, Literacy, and Cognition, use to describe one. The term, dyslexia, and the co-author of All elicits a wide range of reactions. About Tests & Assessments published by Wrightslaw.