A&M Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PG&E Bankruptcy May Not Affect Community Choice Power

Thursday, JANUARY 24, 2019 VOLUME LVI, NUMBER 4 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING DUBLIN, LIVERMORE, PLEASANTON, SUNOL PG&E Bankruptcy May Not Affect Community Choice Power By Ron McNicoll News reports indicate PG&E has such tremendous potential legal li- ability from wildfires that allegedly may have been caused by its power East Bay Community Energy (EBCE) doubts there would be any lines that the firm might not be able to survive financially, unless it ap- negative impact on its power delivery program, if PG&E files bankruptcy, plies for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. PG&E stock value has been according to EBCE CEO Nick Chaset. See Inside Section A dropping, because of the news. Chaset said that EBCE is working on an official statement about the The California Community Choice Association (CalCCA), a group Section A is filled with topic, but he told a reporter that the potential bankruptcy “would have that represents EBCE and other Community Choice Aggregation (CCA) information about arts, people, no meaningful impact on our program.” entities throughout the state, issued a statement on Jan. 14 about PG&E. entertainment and special events. “We go out and buy energy, and serve our customers with energy “CCAs are committed to providing reliable service, clean energy There are education stories, a sources,” said Chaset. EBCE does not necessarily have to buy power at competitive rates, and innovative programs that benefit people, the variety of features, and the arts generated by PG&E. In fact, one motivation for Alameda County su- environment and the economy in communities across California. -

We'll Have a Gay Ol'time: Trangressive Sexulaity and Sexual Taboo In

We’ll have a gay ol’ time: transgressive sexuality and sexual taboo in adult television animation By Adam de Beer Thesis Presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Film Studies in the Faculty of Humanities and the Centre for Film and Media Studies UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN UniversityFebruary of 2014Cape Town Supervisor: Associate Professor Martin P. Botha The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Cape Town. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination at any other university. Adam de Beer February 2014 ii Abstract This thesis develops an understanding of animation as transgression based on the work of Christopher Jenks. The research focuses on adult animation, specifically North American primetime television series, as manifestations of a social need to violate and thereby interrogate aspects of contemporary hetero-normative conformity in terms of identity and representation. A thematic analysis of four animated television series, namely Family Guy, Queer Duck, Drawn Together, and Rick & Steve, focuses on the texts themselves and various metatexts that surround these series. The analysis focuses specifically on expressions and manifestations of gay sexuality and sexual taboos and how these are articulated within the animated diegesis. -

Tv Guide Sydney Yahoo

Tv guide sydney yahoo Continue Open the Mac App Store to buy and download apps. The number one Australian television guide to the App Store. Free for iPhone and iPad with TV listings for each Australian region supporting most major freeview and free-to-air channels. Features: - 100% Australian owned and operated, you can be sure that you are dealing with Aussie - Trust millions of users across the country - Available for iPhone and iPad - Australian freeview and free-to-air TV guide, all major TV channels are available for all Australian regions - Watch TV shows or program details, start and end time - Keep an eye out for your favorite programs, add favorites to your list, easy to check upcoming episodes - Get notifications about upcoming show programs, enter notifications and set reminders for any program - Export to calendar to create calendar events for shows - Explore popular movies and TV shows - Browse the TV guide by channel or category, watch upcoming favorite shows and movies channel - Search for TV guides for shows and episodes , Viewing trend searches - Modern, fast and responsive , the choice is yours - View recommendations for movies in the coming day - Choose to create an account to sync settings on multiple devices (account not required to use the app) - AusTV Plus updates to unlock additional features such as us: no ads, themes, customize categories of manuals and colors, and moreSupported channels: 10, 10 Bold, 10 HD, 10 Peach, 31 Digital, 7, 7 Digital, 7flix, 7HD, 7mate HD, 7TWO, 9, 9Gem, 9Gem HD, 9Go!, 9HD, 9Life, 9Rush, -

Television Academy

Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series For a single episode of a comedy series. Emmy(s) to director(s). VOTE FOR NO MORE THAN FIVE achievements in this category that you have seen and feel are worthy of nomination. (More than five votes in this category will void all votes in this category.) 001 About A Boy Pilot February 22, 2014 Will Freeman is single, unemployed and loving it. But when Fiona, a needy, single mom and her oddly charming 11-year-old son, Marcus, move in next door, his perfect life is about to hit a major snag. Jon Favreau, Director 002 About A Boy About A Rib Chute May 20, 2014 Will is completely heartbroken when Sam receives a job opportunity she can’t refuse in New York, prompting Fiona and Marcus to try their best to comfort him. With her absence weighing on his mind, Will turns to Andy for his sage advice in figuring out how to best move forward. Lawrence Trilling, Directed by 003 About A Boy About A Slopmaster April 15, 2014 Will throws an afternoon margarita party; Fiona runs a school project for Marcus' class; Marcus learns a hard lesson about the value of money. Jeffrey L. Melman, Directed by 004 Alpha House In The Saddle January 10, 2014 When another senator dies unexpectedly, Gil John is asked to organize the funeral arrangements. Louis wins the Nevada primary but Robert has to face off in a Pennsylvania debate to cool the competition. Clark Johnson, Directed by 1 Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series For a single episode of a comedy series. -

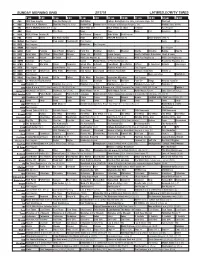

Sunday Morning Grid 2/17/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/17/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Ohio State at Michigan State. (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Day Hockey New York Rangers at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Hockey: Blues at Wild 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid American Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Planet Weird Fox News Sunday News PBC Face NASCAR RaceDay (N) 2019 Daytona 500 (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Grand Canyon Huell’s California Adventures: Huell & Louie 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Jeffress Win Walk Prince Carpenter Intend Min. -

The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21St Century Stand-Up

The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21st Century Stand-Up Comedy Stage © 2018 Rachel Eliza Blackburn M.F.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 2013 B.A., Webster University Conservatory of Theatre Arts, 2005 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Theatre and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Nicole Hodges Persley Dr. Katie Batza Dr. Henry Bial Dr. Sherrie Tucker Dr. Peter Zazzali Date Defended: August 23, 2018 ii The dissertation committee for Rachel E. Blackburn certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21st Century Stand-Up Comedy Stage Chair: Dr. Nicole Hodges Persley Date Approved: Aug. 23, 2018 iii Abstract In 2014, Black feminist scholar bell hooks called for humor to be utilized as political weaponry in the current, post-1990s wave of intersectional activism at the National Women’s Studies Association conference in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Her call continues to challenge current stand-up comics to acknowledge intersectionality, particularly the perspectives of women of color, and to encourage comics to actively intervene in unsettling the notion that our U.S. culture is “post-gendered” or “post-racial.” This dissertation examines ways in which comics are heeding bell hooks’s call to action, focusing on the work of stand-up artists who forge a bridge between comedy and political activism by performing intersectional perspectives that expand their work beyond the entertainment value of the stage. Though performers of color and white female performers have always been working to subvert the normalcy of white male-dominated, comic space simply by taking the stage, this dissertation focuses on comics who continue to embody and challenge the current wave of intersectional activism by pushing the socially constructed boundaries of race, gender, sexuality, class, and able-bodiedness. -

The Advertiser Deserves the Money Will Most Likely Be for New (Tuesday, October 20)

T S G E: [email protected] Ph: 5461-3866 www.maryboroughadvertiser.com.au www.maryboroughbusiness.com.au Published Tuesdays & Fridays No. 20,426 $1.50 c n i T HEALTH T COUNCIL T MDCA HEALTH SERVICE APPOINTS NEW CEO BROILER FARM APPLICATION HEADED TO COUNCIL MARYBOROUGH AND AVOCA UNITE FOR 2020/21 PAGE 3 PAGE 5 SPORT The Maryborough District AdvertiserEst. 1855 Tuesday, October 20, 2020 CAUTIONARY TALE Holly and Rolly the beagles have been Brian Smithʼs closest companions for some time now, after his wife Sandy passed away 18 months ago. The tight knit trio have endured a lot together, including Rollyʼs run in with a brown snake earlier this month — the first confirmed bite for the season and sparking an emergency trip to the vet. Story, Page 7. SMALL STEPS201020 04 Household bubble removed as Premier announces minor changes to COVID restrictions CHRISTIE HARRISON Third Step restrictions, residents are “It’s not so long ago that we had then to find that normal and begin Wednesday last week. Regional Victoria took another now able to host two visitors from 725 cases and there was simply no the process of rebuilding. Four new cases were recorded as step towards reopening at the two households per day at home, and way we could have a debate about “Yes, these lockdowns have come of the latest figures on Monday, and weekend with minor changes to patron limits have been increased for how and when to open,” Mr Andrews with significant hurt and pain and one life was lost to the virus. -

16 March 2018

22,000 copies / month Community News, Local Businesses, Local Events and Free TV Guide 16TH MARCH 2018 - 4TH APRIL 2018 VOL 35 - ISSUE 6 APRIL 20, 21 & 22ND Sandstone FULL STORY ON PAGE 12 MARK VINT Bathroom renovations Sales starting from Buy Direct From the Quarry 9651 2182 $9,900 270 New Line Road Prices Local Experienced Dural NSW 2158 starting from tilers, vinyl installers 9652 1783 to service the [email protected] $59+gst/sq m Gabion Spalls $16.50/T (min) for tiling Hills district. ABN: 84 451 806 754 75mm - 150mm for baskets 1800 733 809 Visit us at unit 3A/827 Old Northern Road, Dural NSW 2158 113 Smallwood Rd Glenorie WWW.DURALAUTO.COM www.duraltiles.com.au June 6 2014:H-H 2011 5/06/2014 11:15 PM Page 7 June 6 2014:H-H 2011 5/06/2014 11:15 PM Page 7 You may be surprised to learn, for instance, that research shows beet greens may: You may be surprised to learn, for instance, that research shows• Help beet ward greens off osteoporosis may: by boosting bone strength •• Help Fight ward Alzheimer's off osteoporosis disease by boosting bone strength •• Fight Strengthen Alzheimer's your immunedisease system by stimulating the production of antibodies and white blood cells • Strengthen your immune system by stimulating the If you'veproduction never of tried antibodies beet greens and white before, blood don't cells let them intimidate you. They can be added raw to vegetable juice If you've never tried beet greens before, don't let them or sautéed lightly right along with other greens like intimidate you. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

Advertiser Motoring

T S G E: [email protected] Ph: 5461-3866 www.maryboroughadvertiser.com.au www.maryboroughbusiness.com.au Published Tuesdays & Fridays No. 20,418 $1.50 c n i T COVID-19 T ELECTIONS T CYCLING CASE NUMBERS DROP TO THREE-MONTH LOW GEOFF LOVETT ANNOUNCES CANDIDACY JESS HITS THE ROAD FOR SOLO 1000 PAGE 3 PAGE 4 SPORT The Maryborough District AdvertiserEst. 1855 Tuesday, September 22, 2020 100 YEARS YOUNG A 100th birthday is a big deal by anyone's books, but long-time Dunolly resident Doris 'Dos' Polinelli insists she feels just the same as she did on her 90th birthday. Born on this day in 1920, Doris has been inundated with letters from family, friends and even the Queen and will celebrate the milestone digitally. Story, Page 7. 220920 07 NAPLAN REVIEW Local schools give mixed responses to NAPLAN recommendations CHRISTIE HARRISON the needs of students, schools and It also recommended tests should The test, which currently runs in Sutton said the school has had Australia’s national standar- parents. NAPLAN (National Assess- include a new assessment of critical May, would be brought forward strong attendance rates in the past dised assessment, NAPLAN, ment Program — Literacy and and creative thinking in STEM, and earlier in the year and results would and is in favour of the new could be set for a major overhaul Numeracy) is an annual assessment change the written section of the be returned within a week. recommendations. in some states including a name for all students in years three, five, assessment to address criticisms While some students can be “Traditionally, particularly over change, testing of critical and seven and nine that covers skills in that the current approach encoura- exempt from sitting the test, the the past few years we’ve had a strong creative thinking in STEM reading, writing, spelling, grammar ges formulaic responses. -

Your Prime Time Tv Guide ABC (Ch2) SEVEN (Ch6) NINE (Ch5) WIN (Ch8) SBS (Ch3) 6Pm the Drum

tv guide PAGE 2 FOR DIGITAL CHOICE> your prime time tv guide ABC (CH2) SEVEN (CH6) NINE (CH5) WIN (CH8) SBS (CH3) 6pm The Drum. 6pm Seven Local News. 6pm Nine News. 6pm News. 6pm Mastermind Australia. 7.00 ABC News. 6.30 Seven News. 7.00 A Current Affair. 6.30 The Project. Presented by Jennifer Byrne. Y 7.30 Gardening Australia. 7.00 Better Homes And Gardens. 7.30 Rugby League. NRL. Round 18. 7.30 The Living Room. 6.30 SBS World News. A 8.30 MotherFatherSon. (M) Caden 8.30 MOVIE Sweet Home Alabama. Penrith Panthers v Parramatta Eels. 8.30 Have You Been Paying 7.30 George W. Bush. (M) Part 1 of 2. D I returns to London. (2002) (PG) Reese Witherspoon, Josh 9.45 Friday Night Knock Off. Attention? (M) 9.30 Cycling. Tour de France. Stage 9.30 Miniseries: The Accident. (M) Lucas. A New York socialite returns 10.35 MOVIE The Last Castle. 9.30 Just For Laughs Uncut. (M) 13. Châtel-Guyon to Puy Mary FR Part 2 of 4. to Alabama. (2001) (M) Robert Redford, James 10.00 Just For Laughs. (MA15+) Cantal. 191.5km mountain stage. 10.20 ABC Late News. 10.45 To Be Advised. Gandolfini. A disgraced general 10.30 The Project. From France. 10.50 The Virus. organises an uprising. 11.30 WIN News. 7pm ABC News. 6pm Seven News. 6pm Nine News Saturday. 6pm To Be Advised. 6.30pm SBS World News. Y 7.30 Father Brown. (PG) Mrs 7.00 Border Patrol. (PG) 7.00 A Current Affair. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 105 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 105 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 144 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, MARCH 12, 1998 No. 26 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was The SPEAKER pro tempore. The UNFAITHFUL called to order by the Speaker pro tem- question is on the Chair's approval of (Mr. DELAY asked and was given per- pore (Mr. BRADY). the Journal. mission to address the House for 1 f The question was taken; and the minute and to revise and extend his re- Speaker pro tempore announced that marks.) DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER the ayes appeared to have it. Mr. DELAY. Mr. Speaker, the Presi- PRO TEMPORE Mr. WELLER. Mr. Speaker, I object dent has been unfaithful to the historic The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- to the vote on the ground that a budget agreement that he signed only fore the House the following commu- quorum is not present and make the last year. According to the Congres- nication from the Speaker: point of order that a quorum is not sional Budget Office, the President's WASHINGTON, DC, present. newest budget plan will wipe out the March 12, 1998. The SPEAKER pro tempore. Pursu- surplus and create a $5 billion deficit I hereby designate the Honorable KEVIN ant to clause 5, rule I, further proceed- by the year 2000. If we did nothing and BRADY to act as Speaker pro tempore on this ings on this question will be postponed.