HAVANA Great Houses Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Cuba News PUBLISHED by CITIZENS COMMITTEE for a FREE CUBA, INC

This document is from the collections at The Robert J. Dole Archive and Special Collections, University of Kansas. http://dolearchive.ku.edu Free Cuba News PUBLISHED BY CITIZENS COMMITTEE FOR A FREE CUBA, INC. Telephone 783-7507 • 617 Albee Building, 1426 G Street, N.W. • Washington 5, D. C. Editor: Daniel James Vol. 1, No. 13, August 31, 1963 INSIDE CUBA NEW SOVIET MILITARY COMPLEX IN PINAR DEL RIO Sources inside Cuba provide facts pointing to the existence of a new Soviet mili tary complex in Cuba 1s westernmost province, Pinar del Rio, which commands the Florida Straits. The main Soviet installation and the site of Soviet military GHQ is at La Gobernadora hills, near the country's principal naval base of Marie!. Five large tunnels have been constructed in the La Gobernadora area. They are 105 ft. wide -- permitting two - way traffic -- and have reinforced ceilings 30 ft . high. Two of the tunnels penetrate La Gobernadora hills laterally for a distance of 6 miles , according to a Rebel Army lieutenant who personally toured the tunnels during their construction and has defected. Guided missiles are secreted in the tunnels, according to reports from the mili tary arm of the Cuban resistance movement. Other sources inside Cuba say that at least one tunnel has been air-conditioned for the storage of nuclear warheads, and that another has been equipped with refrigerating equipment for storing liquid oxygen used for ballis tic missiles. Electrical systems have been installed at the nearby base of Meseta de Anafe, add the latter sources, and are connected with the guided-missile stations at La Gober nadora and the Havana military 11 horseshoe 11 {see ''Military 1Horseshoe 1 Around Havana, 11 FCN No. -

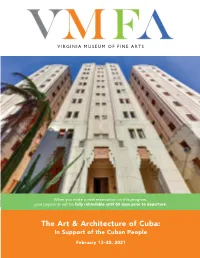

The Art & Architecture of Cuba

VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS When you make a new reservation on this program, your payments will be fully refundable until 60 days prior to departure. The Art & Architecture of Cuba: In Support of the Cuban People February 13–20, 2021 HIGHLIGHTS ENGAGE with Cuba’s leading creators in exclusive gatherings, with intimate discussions at the homes and studios of artists, a private rehearsal at a famous dance company, and a phenomenal evening of art and music at Havana’s Fábrica de Arte Cubano DELIGHT in a private, curator-led tour at the National Museum of Fine Arts of Havana, with its impressive collection of Cuban artworks and international masterpieces from Caravaggio, Goya, Rubens, and other legendary artists CELEBRATE and mingle with fellow travelers at exclusive receptions, including a cocktail reception with a sumptuous dinner in the company of the President of The Ludwig Foundation of Cuba and an after-tours tour and reception at the dazzling Ceramics Museum MEET the thought leaders who are shaping Cuban society, including the former Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs, who will share profound insights on Cuban politics DISCOVER the splendidly renovated Gran Teatro de La Habana Alicia Alonso, the ornately designed, Neo-Baroque- style home to the Cuban National Ballet Company, on a private tour ENJOY behind-the-scenes tours and meetings with workers at privately owned companies, including a local workshop for Havana’s classic vehicles and a factory producing Cuban cigars VENTURE to the picturesque Cuban countryside for When you make a new reservation on this program, a behind-the-scenes tour of a beautiful tobacco plantation your payments will be fully refundable until 60 days prior to departure. -

Servants' Passage

SERVANTS’ PASSAGE: Cultural identity in the architecture of service in British and American country houses 1740-1890 2 Volumes Volume 1 of 2 Aimée L Keithan PhD University of York Archaeology March 2020 Abstract Country house domestic service is a ubiquitous phenomenon in eighteenth and nineteenth century Britain and America. Whilst shared architectural and social traditions between the two countries are widely accepted, distinctive cultural identity in servant architecture remains unexplored. This thesis proposes that previously unacknowledged cultural differences between British and American domestic service can be used to rewrite narratives and re-evaluate the significance of servant spaces. It uses the service architecture itself as primary source material, relying on buildings archaeology methodologies to read the physical structures in order to determine phasing. Archival sources are mined for evidence of individuals and household structure, which is then mapped onto the architecture, putting people into their spaces over time. Spatial analysis techniques are employed to reveal a more complex service story, in both British and American houses and within Anglo-American relations. Diverse spatial relationships, building types and circulation channels highlight formerly unrecognised service system variances stemming from unique cultural experiences in areas like race, gender and class. Acknowledging the more nuanced relationship between British and American domestic service restores the cultural identity of country house servants whose lives were not only shaped by, but who themselves helped shape the architecture they inhabited. Additionally, challenging accepted narratives by re-evaluating domestic service stories provides a solid foundation for a more inclusive country house heritage in both nations. This provides new factors on which to value modern use of servant spaces in historic house museums, expanding understanding of their relevance to modern society. -

Culture Box of Cuba

CUBA CONTENIDO CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................3 Introduction .................................6 Items .............................................8 More Information ........................89 Contents Checklist ......................108 Evaluation.....................................110 AGRADECIMIENTOS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Contributors The Culture Box program was created by the University of New Mexico’s Latin American and Iberian Institute (LAII), with support provided by the LAII’s Title VI National Resource Center grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Contributing authors include Latin Americanist graduate students Adam Flores, Charla Henley, Jennie Grebb, Sarah Leister, Neoshia Roemer, Jacob Sandler, Kalyn Finnell, Lorraine Archibald, Amanda Hooker, Teresa Drenten, Marty Smith, María José Ramos, and Kathryn Peters. LAII project assistant Katrina Dillon created all curriculum materials. Project management, document design, and editorial support were provided by LAII staff person Keira Philipp-Schnurer. Amanda Wolfe, Marie McGhee, and Scott Sandlin generously collected and donated materials to the Culture Box of Cuba. Sponsors All program materials are readily available to educators in New Mexico courtesy of a partnership between the LAII, Instituto Cervantes of Albuquerque, National Hispanic Cultural Center, and Spanish Resource Center of Albuquerque - who, together, oversee the lending process. To learn more about the sponsor organizations, see their respective websites: • Latin American & Iberian Institute at the -

The Breakers/Cornelius Vanderbilt II House National Historic Landmark

__________ ______________ __-_____________-________________ -. ‘"I. *II.fl.* *%tØ*** *.‘" **.‘.i --II * y*’ * - *t_ I 9 - * ‘I teul eeA ‘4 I A I I I UNITED STATES IEPASTMENI OF THE INTERIOP ;‘u is NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Rhode Island .5 1 - COUNTY NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Newport INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER I DATE Type ii!! entries - Complete applicable SeCtions NAME -- OMMON - ... The Breakers AN 0/On HISTORIC: * Vanderbilt Corneiius..II Hcnise ftcOCAT!ON .1 ., * ./1..... H :H5.j_ .. H .O H.H/.H::: :- 51 RECT AND NUMBER: Ochre Point Avenue CITY OR TOWN: flewpcrt STATE COUNTY: - *[7m . CODE Rhode I3land, O2flhO Newport 005 -- CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE tn OWNERSHIP STATUS C/reck One TO THE PUBLIC El District iEj Building LI PubIC Public Acc1ui Si’on: LI Occupied Yes: 0 Restricted El Si to LI Structure Private LI 0 P roess Unoccupied LI Unre.trtcsed Er Oblect LI Both [3 Being Considered j Preservation work I. in progress LI No U PRESENT USE Check One or More as Appropriate LI Agriu Iturol LI 0 overn-ten? LI Pork [3 Transportation [3 Comments DC El C OrIImerC i ol [3 Hdju al [3 Pri vote Residence [3 Other SpocI’ I LI Educational [3 Miii tory [3 Religious - Entertainment Museum Scientific ‘I, LI --__ flAkE; S UWNIrRs Alice FHdik, Gladys raljlqt Peterson, Sylvia S. 5zapary, Nanine -I tltz, Gladys P.. thoras, Cornelia Uarter Roberts; Euaene B. R&erts, Jr. -1 S w STREET ANd NLIMBER: Lu The Breakers, Ochre Point Avenue CITY ** STATE: tjfl OR TOWN: - --.*** CODE Newport Rhode Island, 028b0 lili iLocATIoNcrLEGALDEsRIpTwN 7COURTHOUSr, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. -

Cultural Exchange Trip to Cuba November 10 - 17, 2020

Cultural Exchange Trip to Cuba November 10 - 17, 2020 Tuesday, November 10 1 – 6 pm Settle into the historic Hotel Capri, which was one of the first hotel casinos built by the American mafia in Cuba. Owned by mobster Santo Trafficante and run by actor George Raft, the hotel housed at a time one of the largest casinos in Havana. Located blocks from the University of Havana, Coppelia ice cream, and the Havana seawall, the recent remodeling provides first class amenities. 6:30 pm Orientation meeting and welcome drinks at the hotel 7:00 pm Enjoy a traditional Cuban meal overlooking the Straits of Florida at the Hotel Nacional. Tasty Cuban food served family style with a great view of the Havana sea wall and the old Spanish fortress. Wedenesday, November 11 10:00 am Socio-economic discussion with urban planner Miguel Coyula, whose presentation will touch on housing, infrastructure, investment, and restoration programs. Professor Coyula’s talk will help you better understand Havana’s historical development and what lies ahead for this storied city. 11:30 am Behind-the-scenes walking tour of Old Havana. Explore the historic center and learn about the history and architectural importance of Old Havana, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1982. Venture to the side streets to witness Cuban life first-hand, stopping at local bodegas, markets, and the popular gathering places where Habaneros play dominos and discuss sports, transportation, jobs, and other topics of daily life. Along the way, we will stop at various new, private businesses, including Dador and Cladestina, and meet with owners to discuss the triumphs and challenges of cuentapropistas (the self-employed) in Cuba. -

Cuba / by Amy Rechner

Blastoff! Discovery launches a new mission: reading to learn. Filled with facts and features, each book offers you an exciting new world to explore! This edition first published in 2019 by Bellwether Media, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Bellwether Media, Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 6012 Blue Circle Drive, Minnetonka, MN 55343. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rechner, Amy, author. Title: Cuba / by Amy Rechner. Description: Minneapolis, MN : Bellwether Media, Inc., 2019. | Series: Blastoff! Discovery: Country Profiles | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018000616 (print) | LCCN 2018001146 (ebook) | ISBN 9781626178403 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781681035819 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Cuba--Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC F1758.5 (ebook) | LCC F1758.5 .R43 2019 (print) | DDC 972.91--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018000616 Text copyright © 2019 by Bellwether Media, Inc. BLASTOFF! DISCOVERY and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Bellwether Media, Inc. SCHOLASTIC, CHILDREN’S PRESS, and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc., 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. Editor: Rebecca Sabelko Designer: Brittany McIntosh Printed in the United States of America, North Mankato, MN. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE OLD NEW WORLD 4 LOCATION 6 LANDSCAPE AND CLIMATE 8 WILDLIFE 10 PEOPLE 12 COMMUNITIES 14 CUSTOMS 16 SCHOOL AND WORK 18 PLAY 20 FOOD 22 CELEBRATIONS 24 TIMELINE 26 CUBA FACTS 28 GLOSSARY 30 TO LEARN MORE 31 INDEX 32 THE OLD NEW WORLD OLD HAVANA A family of tourists walks the narrow streets of Old Havana. -

Cultural Pathways to Cuba

Cultural Pathways to Cuba Nov 9-19, 2019 Havana | Matanzas | Varadero Please note: This itinerary is subject to change and will be updated as we get closer to our travel dates, particularly to take advantage of events organized to celebrate Havana 500. Day 1 Havana 9 NOV Saturday 11:00 Arrival in Havana Airport Recommended arrival by 11:00 am for a group transfer. 1:00 Lunch at El Jardín de los Milagros paladar (privately owned restaurant) We’ve planned our first meal at “The Garden of Miracles” to set a auspicious tone for the adventures to come! We’ll meet each other in a patio with vine covered trellises, while sharing a tasty Cuban lunch. Tour the hydroponic garden and the bee hives on the roof where the owners grow herbs and vegetables for the restaurant. 3:30 Check in at Hotel Victoria, Vedado You’ll have some down time to settle in and rest before gathering for a Group Orientation and the Welcome Dinner. 6:00 Group Orientation AltruVistas staff and your Cuban guide will share tips to ensure your journey is fun and safe. We’ll review and agree on processes that will help the group travel experience flow more smoothly, and end with a toast to a fabulous trip! 7:30 Welcome Dinner An unforgettable place to continue your introduction to Havana is the San Cristobal Paladar -- one of the most noted restaurants in the city, serving fine comida criolla. Housed in a turn of the century mansion in Centro Habana, the home was thoughtfully renovated to maintain the spectacular tiles and other original elements, including a large altar in the front room. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 188/Monday, September 28, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 188 / Monday, September 28, 2020 / Notices 60855 comment letters on the Proposed Rule Proposed Rule Change and to take that the Secretary of State has identified Change.4 action on the Proposed Rule Change. as a property that is owned or controlled On May 21, 2020, pursuant to Section Accordingly, pursuant to Section by the Cuban government, a prohibited 19(b)(2) of the Act,5 the Commission 19(b)(2)(B)(ii)(II) of the Act,12 the official of the Government of Cuba as designated a longer period within which Commission designates November 26, defined in § 515.337, a prohibited to approve, disapprove, or institute 2020, as the date by which the member of the Cuban Communist Party proceedings to determine whether to Commission should either approve or as defined in § 515.338, a close relative, approve or disapprove the Proposed disapprove the Proposed Rule Change as defined in § 515.339, of a prohibited Rule Change.6 On June 24, 2020, the SR–NSCC–2020–003. official of the Government of Cuba, or a Commission instituted proceedings For the Commission, by the Division of close relative of a prohibited member of pursuant to Section 19(b)(2)(B) of the Trading and Markets, pursuant to delegated the Cuban Communist Party when the 7 Act, to determine whether to approve authority.13 terms of the general or specific license or disapprove the Proposed Rule J. Matthew DeLesDernier, expressly exclude such a transaction. 8 Change. The Commission received Assistant Secretary. Such properties are identified on the additional comment letters on the State Department’s Cuba Prohibited [FR Doc. -

The Theory of the Cuban Revolution

University of Central Florida STARS PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements 1-1-1962 The theory of the Cuban Revolution Joseph Hansen Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Book is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Hansen, Joseph, "The theory of the Cuban Revolution" (1962). PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements. 280. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism/280 Theory of the by Joseph Hansen PIONEER PUBLISHERS 116 Unhrdty b Nw Yd3, N. Y. In reply to all this, Ssme continued. beeianing ef the year some Cuban he had heard a thowand The came ta see him. "Tbey talked RwoIution is a pmxh whlch- fwses its at lemgtb, with fire, of the Revoludrn, Ideasin&n."This~,theM but I Med h vain to get them to tell ExistentIalIst philcsopber and play- me wheber the new regIme was social- wright held, was logically unmble, Ist or not." but a little abstract. Citing a practical Sartre was prevailed on to vislt Cuba interest in cl-bg up the question of a08 -mine for himself. Upon leav- the theory of the Cuban revohrtiopl, he ing, he offered bis imgmsdmr in en declared: "1t is nmto -. of UPWinter&, ''Ideologk y certainly, the und- - sincere or Revo1uci&" (Ideom end Rwolutlon ) , feigned - of those who say that they which was published ithe March 21 don't know anything or who repmacb isme af tunes de Rerrdurd6R. -

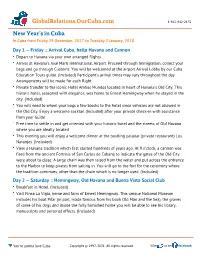

Globalrelations.Ourcuba.Com New Year's in Cuba

GlobalRelations.OurCuba.com 1-815-842-2475 New Year's in Cuba In Cuba from Friday 29 December, 2017 to Tuesday 2 January, 2018 Day 1 – Friday :: Arrival Cuba, hello Havana and Cannon Depart to Havana via your own arranged flights Arrival at Havana’s José Martí International Airport. Proceed through Immigration, collect your bags and go through Customs. You will be welcomed at the airport Arrival Lobby by our Cuba Education Tours guide. (Included) Participant’s arrival times may vary throughout the day. Arrangements will be made for each flight Private transfer to the iconic Hotel Ambos Mundos located in heart of Havana’s Old City. This historic hotel, seasoned with elegance, was home to Ernest Hemingway when he stayed in the city. (Included) You will need to wheel your bags a few blocks to the hotel since vehicles are not allowed in the Old City. Enjoy a welcome cocktail (Included) after your private check-in with assistance from your Guide Free time to settle in and get oriented with your historic hotel and the streets of Old Havana where you are ideally located This evening you will enjoy a welcome dinner at the bustling paladar (private restaurant) Los Naranjos. (Included) View a Havana tradition which first started hundreds of years ago. At 9 o’clock, a cannon was fired from the ancient Fortress of San Carlos de Cabana to indicate the gates of the Old City were about to close. A large chain was then raised from the water and put across the entrance to the Harbor to keep pirates from sailing in. -

VINTAGE CUBA Win Air Canada Flights to Havana WELCOME the CHECK in INTERVIEW

Winter 2012/13 Top tips for winter travel pics VINTAGE CUBA Win Air Canada flights to Havana WELCOME THE CHECK IN INTERVIEW This has been a remarkable summer. World Airline Awards, which are Not only have we celebrated the based on a survey of more than 75th anniversary of Air Canada, 18 million passengers worldwide. we have also played our part in The awards are regarded in the 40 years of teamwork welcoming the Olympic Games to aviation industry as a key London; helping Heathrow to provide benchmarking tool for airline Robert Atkinson, General Manager – Sales UK, Ireland and Northern Europe celebrates great service to customers during passenger satisfaction levels. the busiest period in its history. As 40 years at Air Canada this year. Check In catches up with the man himself... the Official Airline of the Canadian This winter, Air Canada will continue Olympic and Paralympic Teams, to offer more daily flights from the Today Robert Atkinson is the General What’s changed the most? benefit customers with integrated we were in the privileged position UK to Canada than any other airline, Manager – Sales UK, Ireland and I guess technology is the biggest pricing, a wider route network and of welcoming Canadian athletes with up to 63 non-stop flights per Northern Europe, but 40 years ago change. 40 years ago we flew DC8s common administration. onboard Air Canada and flying them week to seven major Canadian cities. he started his career at Air Canada on and today we fly the Boeing 777. to London – very fuel efficiently as We will operate up to four flights the ticket desk, when life in the airline Environmental efficiency is where great What’s your funniest moment? you will see on page 7.