Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) ⇑ Jessica R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild Bees of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument: Richness, Abundance, and Spatio-Temporal Beta-Diversity

Wild bees of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument: richness, abundance, and spatio-temporal beta-diversity Olivia Messinger Carril1, Terry Griswold2, James Haefner3 and Joseph S. Wilson4 1 Santa Fe, NM, United States of America 2 USDA-ARS Pollinating Insects Research Unit, Logan, UT, United States of America 3 Biology Department, Emeritus Professor, Utah State University, Logan, UT, United States of America 4 Department of Biology, Utah State University - Tooele, Tooele, UT, United States of America ABSTRACT Interest in bees has grown dramatically in recent years in light of several studies that have reported widespread declines in bees and other pollinators. Investigating declines in wild bees can be difficult, however, due to the lack of faunal surveys that provide baseline data of bee richness and diversity. Protected lands such as national monuments and national parks can provide unique opportunities to learn about and monitor bee populations dynamics in a natural setting because the opportunity for large-scale changes to the landscape are reduced compared to unprotected lands. Here we report on a 4-year study of bees in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (GSENM), found in southern Utah, USA. Using opportunistic collecting and a series of standardized plots, we collected bees throughout the six-month flowering season for four consecutive years. In total, 660 bee species are now known from the area, across 55 genera, and including 49 new species. Two genera not previously known to occur in the state of Utah were discovered, as well as 16 new species records for the state. Bees include ground-nesters, cavity- and twig-nesters, cleptoparasites, narrow specialists, generalists, solitary, and social species. -

Studies of North American Bees

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) University Studies of the University of Nebraska January 1914 Studies of North American Bees Myron Harmon Swenk University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers Part of the Life Sciences Commons Swenk, Myron Harmon, "Studies of North American Bees" (1914). Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska). 9. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Studies of the University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOL. XIV JANUAR Y 1914 No. I I.-STUDIES OF NORTH AMERICAN BEES BY MYRON HARMON SWENK &+ The present paper is the second of the series proposed in a previous contribution on the famil.\- Nomadidae (arztea, XII, pp. I-II~),and aims to tabulate and list the bees of the family Stelididae occurring in Nebraska, together wilth annotations con- cerning their distribution, comparative abundance and season of flight. As in the previous study, records and descriptions of specimens from outside Nebraska before the writer are included where these seem to add anything to our knowledge of the species concerned. MATERIAL In the studies upon which this paper is based over four hundred specimens have been examined and determined. From the state of Nebraska fifteen species and subspecies are recorded, and of these three species are apparently new. -

Teletusa Limpida (SIGNORET)

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Teletusa limpida (SIGNORET): a Neotropical proconiine leafhopper that mimics megachilid bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea), with notes on Batesian mimicry in the subfamily Cicadellinae (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) G. MEJDALANI, D.M. TAKIYA, M. FELIX, P. CEOTTO & D. YANEGA Abstract Morphological comparisons and field and M. neoxanthoptera. Yellow areas on studies carried out in the Brazilian State of the leafhopper abdomen resemble the Minas Gerais suggested that the proconi- metasomal scopal hairs or the pollen ine leafhopper Teletusa limpida (SlG- carried on the scopa of the bees. The NORET) is a Batesian mimic of bees of the present case of mimicry is compared with family Megachilidae. This leafhopper the two other known cases of mimicry in exhibits the following mimicry-related leafhoppers of the subfamily Cicadellinae characteristics: (1) body densely covered (genera Propetes WALKER and Lissoscarta by conspicuous hairs, especially developed STAL), as well as with similar cases in the on the face and mesoscutellum, (2) disc of Auchenorrhyncha. The appearance of frons forming an approximately right angle mimicry in the Cicadellinae is discussed in with the longitudinal axis of body, (3) a phylogenetic context. fore- and hindwings almost entirely hya- line, (4) abdomen short and expanded lat- erally, and (5) overall coloration dark Key words brown or black with yellow markings. These features are remarkably similar to Proconiini, Cicadellini, mimetic spe- those of four megachilid species that are cies, morphology, phylogeny, Megachili- sympatric with T. limpida in Minas Gerais dae, Vespidae. (Anthodioctes megachiloides (HOLMBERG), Hypanthidiodes subarenarium (SCHWARZ), Hypanthidiodes musciforme (SCHROTTKY), and Megachile meoxanthoptera COCKE- RELL. -

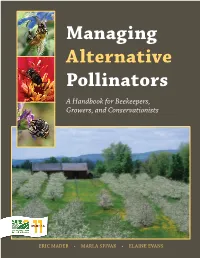

Managing Alternative Pollinators a Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists

Managing Alternative Pollinators A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists ERIC MADER • MARLA SPIVAK • ELAINE EVANS Fair Use of this PDF file of Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists, SARE Handbook 11, NRAES-186 By Eric Mader, Marla Spivak, and Elaine Evans Co-published by SARE and NRAES, February 2010 You can print copies of the PDF pages for personal use. If a complete copy is needed, we encourage you to purchase a copy as described below. Pages can be printed and copied for educational use. The book, authors, SARE, and NRAES should be acknowledged. Here is a sample acknowledgement: ----From Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists, SARE Handbook 11, by Eric Mader, Marla Spivak, and Elaine Evans, and co- published by SARE and NRAES.---- No use of the PDF should diminish the marketability of the printed version. If you have questions about fair use of this PDF, contact NRAES. Purchasing the Book You can purchase printed copies on NRAES secure web site, www.nraes.org, or by calling (607) 255-7654. The book can also be purchased from SARE, visit www.sare.org. The list price is $23.50 plus shipping and handling. Quantity discounts are available. SARE and NRAES discount schedules differ. NRAES PO Box 4557 Ithaca, NY 14852-4557 Phone: (607) 255-7654 Fax: (607) 254-8770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nraes.org SARE 1122 Patapsco Building University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-6715 (301) 405-8020 (301) 405-7711 – Fax www.sare.org More information on SARE and NRAES is included at the end of this PDF. -

Bees in the Genus Rhodanthidium. a Review and Identification

The genus Rhodanthidium is small group of pollinator bees which are found from the Moroccan Atlantic coast to the high mountainous areas of Central Asia. They include both small inconspicuous species, large species with an appearance much like a hornet, and vivid species with rich red colouration. Some of them use empty snail shells for nesting with a fascinating mating and nesting behaviour. This publication gives for the first time a complete Rhodanthidium overview of the genus, with an identification key, the first in the English language. All species are fully illustrated in both sexes with 178 photographs and 60 line drawings. Information is given on flowers visited, taxonomy, and seasonal occurrence; distribution maps are including for all species. This publication summarises our knowledge of this group of bees and aims at stimulating further Supplement 24, 132 Seiten ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. April 2019 research. Kasparek, Bees in the Genus Max Kasparek Bees in the Genus Rhodanthidium A Review and Identification Guide Entomofauna, Supplementum 24 ISSN 02504413 © Maximilian Schwarz, Ansfelden, 2019 Edited and Published by Prof. Maximilian Schwarz Konsulent für Wissenschaft der Oberösterreichischen Landesregierung Eibenweg 6 4052 Ansfelden, Austria EMail: [email protected] Editorial Board Fritz Gusenleitner, Biologiezentrum, Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum, Linz Karin Traxler, Biologiezentrum, Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum, Linz Printed by Plöchl Druck GmbH, 4240 Freistadt, Austria with 100 % renewable energy Cover Picture Rhodanthidium aculeatum, female from Konya province, Turkey Biologiezentrum, Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum, Linz (Austria) Author’s Address Dr. Max Kasparek Mönchhofstr. 16 69120 Heidelberg, Germany Email: Kasparek@tonline.de Supplement 24, 132 Seiten ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. -

Ejt-719 Williams Altanchimeg Byvaltsev.Indd

European Journal of Taxonomy 719: 1–120 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2020.719.1107 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2020 · Williams P.H. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A4500016-C219-4353-B81C-5E0BB520547F Widespread polytypic species or complexes of local species? Revising bumblebees of the subgenus Melanobombus world-wide (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Bombus) Paul H. WILLIAMS 1,*, Dorjsuren ALTANCHIMEG 2, Alexandr BYVALTSEV 3, Roland DE JONGHE 4, Saleem JAFFAR 5, George JAPOSHVILI 6, Sih KAHONO 7, Huan LIANG 8, Maurizio MEI 9, Alireza MONFARED 10, Tshering NIDUP 11, Rifat RAINA 12, Zongxin REN 13, Chawatat THANOOSING 14, Yanhui ZHAO 15 & Michael C. ORR 16 1,14 Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK. 2 Institute of General and Experimental Biology, Peace Avenue 54b, Ulaanbaatar 13330, Mongolia. 3 Novosibirsk State University, ul. Pirogova 2, Novosibirsk, 630090 Russia. 4 Langstraat 105, B-2260 Westerlo, Belgium. 5 South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China. 6 Agricultural University of Georgia, 240 Agmashenebli Alley, Tbilisi, Georgia. 7 Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Jakarta, Indonesia. 8,13,15 Kunming Institute of Botany (Chinese Academy of Sciences), 132 Lanhei Road, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China. 9 Università di Roma ‘Sapienza’, Piazzale Valerio Massimo 6, Roma 00162, Italy. 10 Yasouj University, Zirtol, Yasouj, Iran. 11 Sherubtse College, Royal University of Bhutan, Trashigang, Bhutan. 12 Zoological Survey of India, Pali Road, Jodhpur 342005, Rajasthan, India. 16 Institute of Zoology (Chinese Academy of Sciences), 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang, Beijing 100101, China. -

Wild Bee Declines and Changes in Plant-Pollinator Networks Over 125 Years Revealed Through Museum Collections

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2018 WILD BEE DECLINES AND CHANGES IN PLANT-POLLINATOR NETWORKS OVER 125 YEARS REVEALED THROUGH MUSEUM COLLECTIONS Minna Mathiasson University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Mathiasson, Minna, "WILD BEE DECLINES AND CHANGES IN PLANT-POLLINATOR NETWORKS OVER 125 YEARS REVEALED THROUGH MUSEUM COLLECTIONS" (2018). Master's Theses and Capstones. 1192. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/1192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILD BEE DECLINES AND CHANGES IN PLANT-POLLINATOR NETWORKS OVER 125 YEARS REVEALED THROUGH MUSEUM COLLECTIONS BY MINNA ELIZABETH MATHIASSON BS Botany, University of Maine, 2013 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences: Integrative and Organismal Biology May, 2018 This thesis has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences: Integrative and Organismal Biology by: Dr. Sandra M. Rehan, Assistant Professor of Biology Dr. Carrie Hall, Assistant Professor of Biology Dr. Janet Sullivan, Adjunct Associate Professor of Biology On April 18, 2018 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

Entertainment-Education in Science Education Available on Mobile Devices Interactive Tasks Allow You to Quickly Verify the Acquired Knowledge

Entertainment-education in science education the monograph edited by Grzegorz Karwasz & Małgorzata Nodzyńska 1 2 Entertainment-education in science education the monograph edited by Grzegorz Karwasz & Małgorzata Nodzyńska TORUŃ 2017 3 The monograph edited by: Grzegorz Karwasz & Małgorzata Nodzyńska Rewievers: Cover: Ewelina Kobylańska ISBN .......... 4 Introduction Jan Amos Komensky in „Great Didactics” (Amsterdam, 1657) defined didactics not as a mere process of teaching, but as teaching efficient, lasting and pleasant. He wrote (p. 131) “The school itself should be a pleasant place, and attractive to the eye both within and without. […] If this is done, boys will, in all probability, go to school with as much pleasure as to fairs, where they always hope to see and hear something new.” Further (p. 167) Komensky added: “The desire to know and to learn should be excited in boys in every possible manner.” The idea of linking the fun with didactics finds many followers, expressed also in tittles of activities like “Science is Fun” or “Physics is Fun”. In (Karwasz, Kruk, 2012) we defined three complementary aspects of any bit of information (an exhibition object, a film, a lecture): entertainment (“ludico” in Italian), didactics, and science. The first aspect gives an impression to a student/ visitor/ listener: “how funny it is!”. The didactical aspect induces: “How simple it is!” And the aspect of scientific curiosity induces in best students a question: “How complex it is!” These three functions add-up like three basic colors to give a full spectrum of enlightenment. The entertainment function can be performed in different forms – school, extra-school, complementary to school. -

Bees of Sub-Saharan Africa Poster

Bees of Sub-Saharan Africa It is estimated that there are around 30 000 bee species worldwide of which about 20 500 have been described, 2755 occur in sub-Saharan Africa and about 1200 occur in South Africa. Bees, in many shapes and sizes, pollinate about 80% of all flowering plants and 75% of the vegetables, fruits and nuts we eat. The symbols next to each bee indicate their sociality, where they nest and where they get their food. Megachilidae are long tongued bees with two submarginal cells on their wings that collect pollen Apidae are long tongued bees with two or three submarginal wing cells that collect pollen on their hind legs. under their abdomens. The group comprises almost every type of nest building behaviour. Most are solitary but some are social. Parasitism includes social parasites, cleptoparasites and robbers. ♂ ♂ ♀ ♀ ♀ ♀ ♀ ♂ C ♀ C ♀ ♂ F Pasites ♀ appletoni C C F Cleft Cuckoo Ammobates ♀ Nomada gigas Bee auster Gnathanthidium Wasp Cuckoo Sandwalker prionognathum Bee Cuckoo Bee F Big Jawed Afromelecta fulvohirta Euaspis abdominalis Xylocopa lugubris Fidelia braunsiana Redtailed Cuckoo Bee Carder Bee Coelioxys circumscriptus Large Carpenter Bee Pathwork Cuckoo Bee Pot Bee Cone Cuckoo Bee ♀ ♂ ♀ ♀ ♂ C ♂ ♀ F ♂ C ♂ ♀ ♀ ♂ ♀ ♀ F ♀ ♂ F Ceratina Sphecodopsis Icteranthidium ♀ ♂ Schwarzia emmae moerenhouti Max Cuckoo Bee vespericena F grohmani Small Carpenter Bee Cape Cuckoo Ridge Cheeked Bee C F Hoplitis similis Carder Bee F Lithurgus spiniferus Big Resin Bee Aglaoapis trifasciata Stone Bee Toothed Cuckoo Bee F ♀ ♂ ♀ ♂ Aspidosmia arnoldi ♀ ♂ Ugly Faced Carder Bee ♀ F ♀ ♀ Thyreus pictus Xylocopa scioensis F F Neon Cuckoo Bee Afroheriades sp. ♀ Large Carpenter Bee Compsomelissa Macrogalea candida African Resin Bee Ochreriades F ♀ Stenoheriades sp. -

Efectos De La Fragmentación Del Hábitat Sobre Himenópteros Antófilos (Insecta) En El Bosque Chaqueño Serrano

Universidad Nacional de Córdoba Facultad de Ciencias Exactas Físicas y Naturales Doctorado en Ciencias Biológicas Manuscrito de Tesis para optar al título de Dra. en Ciencias Biológicas Efectos de la fragmentación del hábitat sobre himenópteros antófilos (Insecta) en el Bosque Chaqueño Serrano Doctorando: Bióloga Mariana Laura Musicante Directora: Dra. Adriana Salvo Co-Director: Dr. Leonardo Galetto Centro de Investigaciones Entomológicas de Córdoba (CIEC) Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biología Vegetal (IMBIV-CONICET) Córdoba, Argentina 2013 Comisión Asesora Dr. Marcelo Aizen Laboratorio Ecotono-Centro Regional Universitario Bariloche (CRUB), Universidad Nacional del Comahue e Instituto de Investigaciones en Biodiversidad y Medioambiente (INIBIOMA), San Carlos de Bariloche. Departamento de Botánica, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, Buenos Aires. Dr. Marcelo Cabido Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biología Vegetal-CONICT. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Dra. Adriana Salvo Centro de Investigaciones Entomológicas de Córdoba. Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biología Vegetal-CONICT Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Defensa Oral y Pública Lugar y fecha: Calificación: Tribunal ______________________________ _____________________________________ Firma Aclaración ______________________________ _____________________________________ Firma Aclaración ______________________________ ____________________________________ Firma Aclaración A esos pequeños seres que zumbaban ayer y a los que todavía zumban hoy Efectos de la fragmentación del hábitat -

Effects of Invasive Plant Species on Native Bee Communities in the Southern Great Plains

EFFECTS OF INVASIVE PLANT SPECIES ON NATIVE BEE COMMUNITIES IN THE SOUTHERN GREAT PLAINS By KAITLIN M. O’BRIEN Bachelor of Science in Rangeland Ecology & Management Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 2015 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 2017 EFFECTS OF INVASIVE PLANT SPECIES ON NATIVE BEE COMMUNITIES IN THE SOUTHERN GREAT PLAINS Thesis Approved: Dr. Kristen A. Baum Thesis Adviser Dr. Karen R. Hickman Dr. Dwayne Elmore ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to begin by thanking my advisor, Dr. Kristen Baum, for all of her guidance and expertise throughout this research project. She is an exemplary person to work with, and I am so grateful to have shared my graduate school experience with her. I would also like to recognize my committee members, Dr. Karen Hickman and Dr. Dwayne Elmore, both of whom provided valuable insight to this project. A huge thank you goes out to the Southern Plains Network of the National Park Service, specifically Robert Bennetts and Tomye Folts-Zettner. Without them, this project would not exist, and I am forever grateful to have been involved with their network and parks, both as a research student and summer crew member. A special thank you for Jonathin Horsely, who helped with plot selection, summer sampling, and getting my gear around. I would also like to thank the Baum Lab members, always offering their support and guidance as we navigated through graduate school. And lastly, I would like to thank my family, especially my fiancé Garrett, for believing in me and supporting me as I pursued my goals. -

Oil Plant Pollination Systems

BIONOMY AND HOST PLANT FINDING IN OIL COLLECTING BEES Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades Dr. rer. nat. an der Fakultät Biologie/Chemie/Geowissenschaften der Universität Bayreuth vorgelegt von Irmgard Schäffler Bayreuth, 2012 Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde von August 2008 bis Januar 2012 am Lehrstuhl Pflanzensystematik der Universität Bayreuth unter Betreuung von Herrn PD Dr. Stefan Dötterl angefertigt. Sie wurde von der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft gefördert (DO 1250/3-1). Dissertation eingereicht am: 8. Februar 2012 Zulassung durch die Prüfungskommission: 16. Februar 2012 Wissenschaftliches Kolloquium: 16. Mai 2012 Amtierende Dekanin: Prof. Dr. Beate Lohnert Prüfungsausschuss: PD Dr. Stefan Dötterl (Erstgutachter) PD Dr. Gregor Aas (Zweitgutachter) PD Dr. Ulrich Meve (Vorsitz) Prof. Dr. Konrad Dettner Prof. Dr. Karlheinz Seifert Prof. Dr. Klaus H. Hoffmann This dissertation is submitted as a ‘Cumulative Thesis’ that includes four publications: two published articles, one submitted article, and one article in preparation for submission. List of Publications 1) Schäffler I., Dötterl S. 2011. A day in the life of an oil bee: phenology, nesting, and foraging behavior. Apidologie, 42: 409-424. 2) Dötterl S., Milchreit K., Schäffler I. 2011. Behavioural plasticity and sex differences in host finding of a specialized bee species. Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Neuroethology, Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology, 197: 1119-1126. 3) Schäffler I., Balao F., Dötterl S. Floral and vegetative cues in oil-secreting and non-oil secreting Lysimachia species. Annals of Botany, doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs101. In preparation for submission to Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: 4) Schäffler I., Steiner K. E., Haid M., Gerlach G., Johnson S.