Sleep Patterns and Predictors of College Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campus Cops Corner

January 31, 2011 Volume 4, Issue 1 Pikes Peak Community College Campus Cops Corner Important Numbers & -Public Safety Tips for the websites: 24-7 Emergency PPCC Community- Number: 502-2911 Emergency Alert Sign Up: www.ppcc.edu/ Public Safety Newsletter alert Crime Stoppers Just like the rest of you, I’m struggling to make sense out of the madness which 634-STOP (7867) impacted Tucson and the rest of the country earlier this month. In the wake of Anonymous Reporting John Hinckley’s 1981 assassination attempt of President Ronald Reagan, the www.SAFE2TELL.org April 13, 1981, issue of Time magazine quoted President John Kennedy who said, “If anyone wants to do it, no amount of protection is enough. All a man needs is a willingness to trade his life for mine." While the discussion regarding 1-877-542-7233 civility during public discourse is interesting, I prefer to focus on the more tangible issue of “What do we do if we’re present when it happens?” Ken Hilte, MSM, Chief Of Police Department of Public Safety 5675 South Academy Blvd., A-100 Colorado Springs, CO 80906 Another Spree Shooter The January 24, 2011, issue of Time magazine reports that the emotionally disturbed Tucson gunman fired 31 rounds in 15 seconds. Nineteen people were wounded and six died. Reports indicate that while Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords was the shooter’s intended and first victim, shooting her from a distance of two - three feet, the remaining victims were struck as the shooter randomly fired rounds at the crowd. The shooter was stopped when bystanders, men and women alike, pounced on him. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

Introduction

Introduction Mircea Pitici In the fourth annual volume of The Best Writing on Mathematics series, we present once again a collection of recent articles on various aspects re- lated to mathematics. With few exceptions, these pieces were published in 2012. The relevant literature I surveyed to compile the selection is vast and spread over many publishing venues; strict limitation to the time frame offered by the calendar is not only unrealistic but also undesirable. I thought up this series for the first time about nine years ago. Quite by chance, in a fancy, and convinced that such a series existed, I asked in a bookstore for the latest volume of The Best Writing on Mathematics. To my puzzlement, I learned that the book I wanted did not exist—and the remote idea that I might do it one day was born timidly in my mind, only to be overwhelmed, over the ensuing few years, by unusual ad- versity, hardship, and misadventures. But when the right opportunity appeared, I was prepared for it; the result is in your hands. Mathematicians are mavericks—inventors and explorers of sorts; they create new things and discover novel ways of looking at old things; they believe things hard to believe, and question what seems to be obvi- ous. Mathematicians also disrupt patterns of entrenched thinking; their work concerns vast streams of physical and mental phenomena from which they pick the proportions that make up a customized blend of ab- stractions, glued by tight reasoning and augmented with clues glanced from the natural universe. This amalgam differs from one mathemati- cian to another; it is “purer” or “less pure,” depending on how little or how much “application” it contains; it is also changeable, flexible, and adaptable, reflecting (or reacting to) the social intercourse of ideas that influences each of us. -

Flying the Line Flying the Line the First Half Century of the Air Line Pilots Association

Flying the Line Flying the Line The First Half Century of the Air Line Pilots Association By George E. Hopkins The Air Line Pilots Association Washington, DC International Standard Book Number: 0-9609708-1-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 82-073051 © 1982 by The Air Line Pilots Association, Int’l., Washington, DC 20036 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Printing 1982 Second Printing 1986 Third Printing 1991 Fourth Printing 1996 Fifth Printing 2000 Sixth Printing 2007 Seventh Printing 2010 CONTENTS Chapter 1: What’s a Pilot Worth? ............................................................... 1 Chapter 2: Stepping on Toes ...................................................................... 9 Chapter 3: Pilot Pushing .......................................................................... 17 Chapter 4: The Airmail Pilots’ Strike of 1919 ........................................... 23 Chapter 5: The Livermore Affair .............................................................. 30 Chapter 6: The Trouble with E. L. Cord .................................................. 42 Chapter 7: The Perils of Washington ........................................................ 53 Chapter 8: Flying for a Rogue Airline ....................................................... 67 Chapter 9: The Rise and Fall of the TWA Pilots Association .................... 78 Chapter 10: Dave Behncke—An American Success Story ......................... 92 Chapter 11: Wartime............................................................................. -

MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where Everyone Goes for Scripts and Writers™

DECEMBER VOLUME 17 2017 MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers™ Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer PAGE 8 Q&A with Producer Lauren de Normandie of Status Media & Entertainment PAGE 14 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! CONTENTS Contest/Festival Winners 4 Feature Scripts – FIND YOUR Grouped by Genre SCRIPTS FAST 5 ON INKTIP! Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer 8 INKTIP OFFERS: Q&A with Producer Lauren • Listings of Scripts and Writers Updated Daily de Normandie of Status Media • Mandates Catered to Your Needs & Entertainment • Newsletters of the Latest Scripts and Writers 14 • Personalized Customer Service • Comprehensive Film Commissions Directory Scripts Represented by Agents/Managers 40 Teleplays 43 You will find what you need on InkTip Sign up at InkTip.com! Or call 818-951-8811. Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they place their scripts on our site. 3 WHAT PEOPLE SAY ABOUT INKTIP WRITERS “[InkTip] was the resource that connected “Without InkTip, I wouldn’t be a produced a director/producer with my screenplay screenwriter. I’d like to think I’d have – and quite quickly. I HAVE BEEN gotten there eventually, but INKTIP ABSOLUTELY DELIGHTED CERTAINLY MADE IT HAPPEN WITH THE SUPPORT AND FASTER … InkTip puts screenwriters into OPPORTUNITIES I’ve gotten through contact with working producers.” being associated with InkTip.” – ANN KIMBROUGH, GOOD KID/BAD KID – DENNIS BUSH, LOVE OR WHATEVER “InkTip gave me the access that I needed “There is nobody out there doing more to directors that I BELIEVE ARE for writers than InkTip – nobody. -

Auditing the Cost of the Virginia Tech Massacre How Much We Pay When Killers Kill

THE ASSOCIATED PRESS/M ASSOCIATED THE AR Y AL Y ta FF ER Auditing the Cost of the Virginia Tech Massacre How Much We Pay When Killers Kill Anthony Green and Donna Cooper April 2012 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Auditing the Cost of the Virginia Tech Massacre How Much We Pay When Killers Kill Anthony Green and Donna Cooper April 2012 Remembering those we lost The Center for American Progress opens this report with our thoughts and prayers for the 32 men and women who died on April 16, 2007, on the Virginia Tech campus in Blacksburg, Virginia. We light a candle in their memory. Let the loss of those indispensable lives allow us to examine ways to prevent similar tragedies. — Center for American Progress Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Determining the cost of the Virginia Tech massacre 7 Virginia Tech’s costs 14 Commonwealth of Virginia’s costs 16 U.S. government costs 17 Health care costs 19 What can we learn from spree killings? 24 Analysis of the background check system that failed Virginia Tech 29 Policy recommendations 36 The way forward 38 About the authors and acknowledgements 39 Appendix A: Mental history of Seung-Hui Cho 45 Appendix B: Brief descriptions of spree killings, 1984–2012 48 Endnotes Introduction and summary Five years ago, on April 16, 2007, an English major at Virginia Tech University named Seung-Hui Cho gunned down and killed 32 people, wounded another 17, and then committed suicide as the police closed in on him on that cold, bloody Monday. Since then, 12 more spree killings have claimed the lives of another 90 random victims and wounded another 92 people who were in the wrong place at the wrong time when deranged and well-armed killers suddenly burst upon their daily lives. -

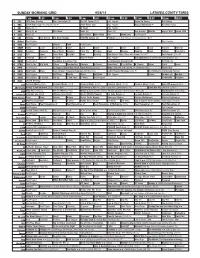

Sunday Morning Grid 9/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Tunnel to Towers Bull Riding 4 NBC 2014 Ryder Cup Final Day. (4) (N) Å 2014 Ryder Cup Paid Program Access Hollywood Å Red Bull Series 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Sea Rescue Wildlife Exped. Wild Exped. Wild 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Green Bay Packers at Chicago Bears. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program The Specialist ›› (1994) Sylvester Stallone. (R) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) La Arrolladora Banda Limón Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue (2012) Baby’s Day Out ›› (1994) Joe Mantegna. -

Print Prt4470417888201353876.Tif

U.S. Department of Homeland Security U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Administrative Appeals Office (AAO) 20 Massachusetts Ave., N.W., MS 2090 Washington, DC 20529-2090 U.S. Citizenship (b)(6) and Immigration Services DATE: MAY 1 3 2015 FILE#: IN RE: Petitioner: Beneficiary: PETITION: Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker Pursuant to Section 101(a)(15)(H)(i)(b) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(15)(H)(i)(b) ON BEHALF OF PETITIONER: INSTRUCTIONS: Enclosed is the non-precedent decision of the Administrative Appeals Office (AAO) for your case. If you believe we incorrectly decided your case, you may file a motion requesting us to reconsider our decision and/or reopen the proceeding. The requirements for motions are located at 8 C.P.R. § 103.5. Motions must be filed on a Notice of Appeal or Motion (Form I-290B) within 33 days of the date of this decision. The Form I-290B web page (www.uscis.gov/i-290b) contains the latest information on fee, filing location, and other requirements. Please do not mail any motions directly to the AAO. Thank you, Ron Rosenberg Chief, Administrative Appeals Office www.uscis.gov (b)(6) NON-PRECEDENT DECISION Page 2 DISCUSSION: The Director, Vermont Service Center, denied the nonimmigrant visa petition. The matter is now before the Administrative Appeals Office on appeal. The appeal will be dismissed. I. PROCEDURAL AND FACTUAL BACKGROUND On the Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker (Form I-129), the petitioner describes itself as a 57-employee "Design of digital products" firm established in In order to employ the beneficiary in what it designates as a "StaffAccountant" position, the petitioner seeks to classify her as a nonimmigrant worker in a specialty occupation pursuant to section 10l(a)(15)(H)(i)(b) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (the Act), 8 U.S.C. -

Arrests Among Emotionally Disturbed Violent and Assaultive Individuals Following Minimal Versus Lengthy Intervention Through North Carolina's Willie M Program

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology Copyright 1990 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 1990, Vol. 58, No. 6,720-728 0022-006X/90/$00.75 Arrests Among Emotionally Disturbed Violent and Assaultive Individuals Following Minimal Versus Lengthy Intervention Through North Carolina's Willie M Program John R. Weisz Bernadette R. Walter University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Orange-Person-Chatham Mental Health Center Chapel Hill, North Carolina Bahr Weiss Vanderbilt University Gustavo A. Fernandez and Victoria A. Mikow Division of Mental Health, Developmental Disabilities, and Substance Abuse Services North Carolina Department of Human Resources Time to first arrest after termination of Willie M Program services was compared in 2 groups of former clients. All Ss had met program criteria and "aged out" after their 18th birthday, but the two groups differed in duration and extent of intervention received: (a) A short-certification group (n = 21), because they turned 18 near the 1981 program start date, had received Willie M services for a mean of only 26 days (all cases < 3 months); (b) a long-certification group (n = 147) averaged 896 days in the program (all cases > 1 year). The groups did not differ significantly in gender or race; geographic region; IQ; diagnosis according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd. ed. (DSM-III, American Psychiatric Association, 1980); or age at earliest antisocial acts. A survival analysis compared the short and long groups on proportion avoiding arrest as a function of time since aging out. The long group showed slightly better arrest survival, but survival curves for the 2 groups did not differ reliably. -

Slightly Disturbed a Mathematical Approach to Oscillations and Waves

Slightly Disturbed A Mathematical Approach to Oscillations and Waves Brooks Thomas Lafayette College Second Edition 2017 Contents 1 Simple Harmonic Motion 4 1.1 Equilibrium, Restoring Forces, and Periodic Motion . ........... 4 1.2 Simple Harmonic Oscillator . ...... 5 1.3 Initial Conditions . ....... 8 1.4 Relation to Cirular Motion . ...... 9 1.5 Simple Harmonic Oscillators in Disguise . ....... 9 1.6 StateSpace ....................................... ....... 11 1.7 Energy in the Harmonic Oscillator . ........ 12 2 Simple Harmonic Motion 16 2.1 Motivational Example: The Motion of a Simple Pendulum . .......... 16 2.2 Approximating Functions: Taylor Series . ........... 19 2.3 Taylor Series: Applications . ........ 20 2.4 TestsofConvergence............................... .......... 21 2.5 Remainders ........................................ ...... 22 2.6 TheHarmonicApproximation. ........ 23 2.7 Applications of the Harmonic Approximation . .......... 26 3 Complex Variables 29 3.1 ComplexNumbers .................................... ...... 29 3.2 TheComplexPlane .................................... ..... 31 3.3 Complex Variables and the Simple Harmonic Oscillator . ......... 32 3.4 Where Making Things Complex Makes Them Simple: AC Circuits . ......... 33 3.5 ComplexImpedances................................. ........ 35 4 Introduction to Differential Equations 37 4.1 DifferentialEquations ................................ ........ 37 4.2 SeparationofVariables............................... ......... 39 4.3 First-Order Linear Differential Equations -

On Linear Systems Disturbed by Wide-Band Noise

On linear systems disturbed by wide-band noise Agamirza E. Bashirov Department of Mathematics, Eastern Mediterranean University Gazimagusa, Mersin 10, Turkey [email protected] Institute of Cybernetics, Azerbaijan Academy of Sciences F. Agayev St. 9, Baku-370141, Azerbaijan Keywords: Wide-band noise, white noise, stochastic sys- function £ is called an autocovariance function. The wide- tem, filtering. band noise process ³ is said to be stationary if the autoco- × " variance function £ depends only on (see [1]). If is so small that it is normally assumed to be 0, then the wide-band Abstract noise process ³ is transformed into a white noise process. As it was mentioned, in many fields such substitution gives rise An approach, based on a distributed delay, is presented to to tangible distortions. handle wide-band noise processes. This approach is closely There are different techniques of handling and working related with the semigroups of right translation and allows with the wide-band noise processes. For example, in [2] the a reduction of a wide-band noise driven linear system to a approximate approach is used. Another approach, based on white noise driven linear system. This reduction is applied a representation of wide-band noise as a distributed delay of to the Kalman-Bucy filtering in order to modify it to a wide- white noise, is suggested in [3]. band noise driven linear system. In [3, 4] the Kalman-Bucy estimation results are modified to a wide-band noise driven systems. The proofs of respec- tive results are based on the duality principle and, technically, 1 Introduction they are routine being useless if one tries to modify them to nonlinear systems.