Theda Pittman (18 Pages)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast Applications 9/30/2013

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28084 Broadcast Applications 9/30/2013 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING MA BAL-20130822AER WBEC 2714 GAMMA BROADCASTING, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended E 1420 KHZ MA , PITTSFIELD From: GAMMA BROADCASTING, LLC To: GREG REED Form 314 MA BAL-20130822AES WUPE 71436 GAMMA BROADCASTING, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended E 1110 KHZ MA , PITTSFIELD From: GAMMA BROADCASTING, LLC To: GREG REED Form 314 CLASS A TV APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING GA BALTVA-20130925ANZ WBFL-CA 48763 NEW AGE MEDIA OF Voluntary Assignment of License TALLAHASSEE LICENSE, LLC E CHAN-13 From: NEW AGE MEDIA OF TALLAHASSEE, LLC GA , VALDOSTA To: TALLAHASSEE (WTLH-TV) LICENSEE, INC. Form 314 GA BALTTA-20130925AOA WBVJ-LP 23487 NEW AGE MEDIA OF Voluntary Assignment of License TALLAHASSEE LICENSE, LLC E CHAN-35 From: NEW AGE MEDIA OF TALLAHASSEE, LLC GA , VALDOSTA To: TALLAHASSEE (WTLH-TV) LICENSEE, INC. Form 314 FL BALTTA-20130925AOE WYME-CA 7726 NEW AGE MEDIA OF Voluntary Assignment of License GAINESVILLE LICENSE, LLC E CHAN-45 From: NEW AGE MEDIA OF GAINESVILLE LICENSE, LLC FL , GAINESVILLE To: WGFL LICENSEE, LLC Form 314 Page 1 of 53 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. -

Smoke Communication Strategy and Appendices 2007

A W F C G S M O K E E D U C A T I O N C Smoke Education Communication Strategy O M v.2007 M U N I C A T I O N S Approved: Date: T R A _____________________________ __________________ T AWFCG Chair E G Y v.2007 AWFCG Smoke Education Communications Strategy Page 2 of 11 02/26/07 Table of Contents Section Page / Appendix Purpose 3 Background 3 Communication Goals 3 General Audiences 3 Strategy 4 Tactics 5 Success 6 Tools and Products 6 Target Audiences 6 Target Media 8 Appendices 11 News Release A Key Messages B Talking Points C Public Service Announcement D Poster E Flyer F Web Site Plan G Display Panel 1 H Display Panel 2 I v.2007 AWFCG Smoke Education Communications Strategy Page 3 of 11 02/26/07 Purpose To provide members of the Alaska Wildland Fire Coordinating Group (AWFCG) with a communication strategy to engage the public in smoke information from wildland fires which include prescribe fires, fire use and wildfires, occurring in the State of Alaska. Background The increase in smoke throughout Alaska during the 2004 and 2005 fire seasons hampered fire suppression operations, aviation operations, motor vehicle operations, tourism and recreation. This strategy provides a collective approach to informing the public about smoke-related issues. Communication Goals · Develop a set of key messages to be used by AWFCG member organizations in order to project one voice in a unified effort regarding smoke issues and mitigation measures. · Provide focused communication products that support the communication goals of this strategy. -

Meteorologia

MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA METEOROLOGIA ICA 105-1 DIVULGAÇÃO DE INFORMAÇÕES METEOROLÓGICAS 2006 MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO METEOROLOGIA ICA 105-1 DIVULGAÇÃO DE INFORMAÇÕES METEOROLÓGICAS 2006 MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO PORTARIA DECEA N° 15/SDOP, DE 25 DE JULHO DE 2006. Aprova a reedição da Instrução sobre Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas. O CHEFE DO SUBDEPARTAMENTO DE OPERAÇÕES DO DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO, no uso das atribuições que lhe confere o Artigo 1°, inciso IV, da Portaria DECEA n°136-T/DGCEA, de 28 de novembro de 2005, RESOLVE: Art. 1o Aprovar a reedição da ICA 105-1 “Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas”, que com esta baixa. Art. 2o Esta Instrução entra em vigor em 1º de setembro de 2006. Art. 3o Revoga-se a Portaria DECEA nº 131/SDOP, de 1º de julho de 2003, publicada no Boletim Interno do DECEA nº 124, de 08 de julho de 2003. (a) Brig Ar RICARDO DA SILVA SERVAN Chefe do Subdepartamento de Operações do DECEA (Publicada no BCA nº 146, de 07 de agosto de 2006) MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO PORTARIA DECEA N° 33 /SDOP, DE 13 DE SETEMBRO DE 2007. Aprova a edição da emenda à Instrução sobre Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas. O CHEFE DO SUBDEPARTAMENTO DE OPERAÇÕES DO DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO, no uso das atribuições que lhe confere o Artigo 1°, alínea g, da Portaria DECEA n°34-T/DGCEA, de 15 de março de 2007, RESOLVE: Art. -

North Pole Road/Rail Crossing Reduction Project

Scoping Summary Report North Pole Road/Rail Crossing Reduction Project May 2011 SCOPING SUMMARY REPORT NORTH POLE ROAD/RAIL CROSSING REDUCTION PROJECT NORTH POLE, ALASKA Prepared for: Alaska Railroad Corporation 327 West Ship Creek Avenue Anchorage, Alaska 99501 Prepared by: DOWL HKM 4041 B Street Anchorage, Alaska 99503 (907) 562-2000 W.O. 60432 May 2011 Scoping Summary Report North Pole, Alaska North Pole Road/Rail Crossing Reduction Project W.O. 60432 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 1.1 General ..............................................................................................................................1 1.2 Project Team .....................................................................................................................2 1.3 Public and Agency Outreach Methods .............................................................................2 1.3.1 Mailing List of Potentially Affected Interests ............................................................3 1.3.2 Informational Flyer/Meeting Announcement .............................................................3 1.3.3 Advertisements ...........................................................................................................3 1.3.4 Project Website ...........................................................................................................4 1.3.5 Project E-Mail Address ...............................................................................................4 -

FY 2016 and FY 2018

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Appropriation Request and Justification FY2016 and FY2018 Submitted to the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee and the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee February 2, 2015 This document with links to relevant public broadcasting sites is available on our Web site at: www.cpb.org Table of Contents Financial Summary …………………………..........................................................1 Narrative Summary…………………………………………………………………2 Section I – CPB Fiscal Year 2018 Request .....……………………...……………. 4 Section II – Interconnection Fiscal Year 2016 Request.………...…...…..…..… . 24 Section III – CPB Fiscal Year 2016 Request for Ready To Learn ……...…...…..39 FY 2016 Proposed Appropriations Language……………………….. 42 Appendix A – Inspector General Budget………………………..……..…………43 Appendix B – CPB Appropriations History …………………...………………....44 Appendix C – Formula for Allocating CPB’s Federal Appropriation………….....46 Appendix D – CPB Support for Rural Stations …………………………………. 47 Appendix E – Legislative History of CPB’s Advance Appropriation ………..…. 49 Appendix F – Public Broadcasting’s Interconnection Funding History ….…..…. 51 Appendix G – Ready to Learn Research and Evaluation Studies ……………….. 53 Appendix H – Excerpt from the Report on Alternative Sources of Funding for Public Broadcasting Stations ……………………………………………….…… 58 Appendix I – State Profiles…...………………………………………….….…… 87 Appendix J – The President’s FY 2016 Budget Request...…...…………………131 0 FINANCIAL SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING’S (CPB) BUDGET REQUESTS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016/2018 FY 2018 CPB Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting requests a $445 million advance appropriation for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This is level funding compared to the amount provided by Congress for both FY 2016 and FY 2017, and is the amount requested by the Administration for FY 2018. -

Hometown, Alaska” on Alaska Public Media Radio (KSKA FM 91.1)

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Mikel Insalaco Marketing & Promotions Manager Phone: (907) 550-8481 Email: [email protected]. Dr. E.J.R. David joins Kathleen McCoy as Host of Local Weekly Radio Program “Hometown, Alaska” on Alaska Public Media Radio (KSKA FM 91.1) ANCHORAGE, ALASKA – March 1, 2021 – Alaska Public Media (AKPM) is pleased to announce that Dr. E.J.R. David will join Kathleen McCoy as a recurring host on AKPM’s local, weekly radio program Hometown, Alaska. Dr. David will make his debut show appearance on March 8, 2021 and will return to host one show episode each month. The weekly show, which broadcasts every Monday at 10 a.m., repeating at 8 p.m., is available for listeners to stream online at alaskapublic.org, on the go using the AKPM or NPR One app, and over the air Alaska Public Media Radio, KSKA FM 91.1. Hometown, Alaska, which has been on-air since 2009, features in-depth conversations with leaders and decision- makers in local and statewide government, social service agencies, educational institutions and cultural groups. “We are thrilled Dr. E.J. David will be joining Kathleen McCoy as host of Hometown, Alaska.” said Linda Wei, Chief Content Officer of Alaska Public Media. “His expertise in psychology and ethnic minority issues brings a new and welcomed perspective to the show and Alaska Public Media." Dr. David was born in the Philippines, and grew up in Pasay, Las Pinas, Makati, and Utkiagvik, Alaska. He obtained his Bachelor's Degree in Psychology from the University of Alaska Anchorage, and Master of Arts and Doctoral Degrees in Clinical-Community Psychology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. -

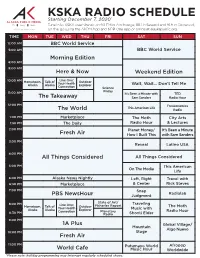

Kska Radio Schedule

KSKA RADIO SCHEDULE Starting December 7, 2020* Tune in to KSKA over-the-air on 91.1 FM in Anchorage, 88.1 in Seward and 91.9 in Girdwood, on-the-go using the AKPM App and NPR One app or online at alaskapublic.org. TIME MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 12:00 AM BBC World Service 5:00 AM BBC World Service Morning Edition 6:00 AM 9:00 AM Here & Now Weekend Edition 10:00 AM Hometown, Talk of Line One: Outdoor Alaska Alaska Your Health Explorer Wait, Wait... Don’t Tell Me Connection Science Friday 11:00 AM It’s Been a Minute with TED The Takeaway Sam Sanders Radio Hour 12:00 PM Freakonomics This American Life The World Radio 1:00 PM Marketplace The Moth City Arts 1:30 PM The Daily Radio Hour & Lectures 2:00 PM Planet Money/ It’s Been a Minute Fresh Air How I Built This with Sam Sanders 3:00 PM Reveal Latino USA 4:00 PM All Things Considered All Things Considered 5:00 PM This American On The Media Life 6:00 PM Alaska News Nightly Left, Right Travel with 6:30 PM Marketplace & Center Rick Steves 7:00 PM Snap Radiolab PBS NewsHour Judgment State of Art/ 8:00 PM Traveling Line One: Fisheries Report The Moth Hometown, Talk of Your Health Outdoor Music with Alaska Alaska Connection Explorer Planetary Radio Hour 8:30 PM Radio Shonti Elder 9:00 PM 1A Plus Global Village/ Mountain Algo Nuevo 10:00 PM Stage Fresh Air 11:00 PM Putumayo World Afropop World Cafe Music Hour Worldwide *Please note: holiday programming may interrupt regularly scheduled shows. -

CPB, PBS Partner with Alaska Public Media to Support Early Science and Literacy Learning

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Mikel Insalaco Marketing & Promotions Manager Phone: (907) 550-8481 Email: [email protected] CPB, PBS Partner With Alaska Public Media to Support Early Science and Literacy Learning Alaska Public Media Receives Ready To Learn Grant to Form Community Partnership to Help Children in Low-Income Neighborhoods ANCHORAGE, ALASKA - December 12, 2018 - The Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) and PBS recently announced that public media station Alaska Public Media (AKPM) has been awarded $175,000 to work with community partners to provide science and literacy resources for the youngest learners to underserved areas. Alaska Public Media is one of 14 public media stations nationwide to receive a Community Collaboratives for Early Learning and Media (CC-ELM) grant this year, joining 16 other public media stations doing similar work through a community engagement model to help the youngest learners in their communities. This effort is part of a five-year Ready To learn grant awarded to CPB and PBS through the U.S. Department of Education’s Ready To Learn Initiative to advance new tools supporting personalized and adaptive content for children and parents, establish a network of community collaboratives, and conduct efficacy research on the educational resources provided. "Since arriving at Alaska Public Media in the spring of 2016, our team has committed to building strong collaborative relationships with early childhood education partners in Anchorage,” said Ed Ulman, CEO/General Manager of AKPM. “We look forward to working with leading partners including Best Beginnings, Anchorage Libraries, Boys and Girls Clubs, Cook Inlet Housing Authority, and the Anchorage Museum to engage our youngest learners with high-quality PBS KIDS educational content." The grant will enable AKPM to work closely with various community partners to maximize the impact of new PBS KIDS science and literacy-based programming, mobile apps and digital games from trusted series “Ready Jet Go!” and “Odd Squad” along with other media properties. -

Public Radio in Mid America

APPENDIX A To PRROs Comments SUMMARY OF STATISTICS IN APPENDIX A Total Number of Public Radio FM Translator Stations in Appendix A 220 100% of those reporting Total (Combined) Estimated Population Served for Public Radio 4,852,610 persons - FM Translators in Appendix A Total Number of Rural Communities Served by Public 152 69.09% of those Radio FM Translator Stations in reporting Appendix A Total Number of Public Radio FM Translators in Appendix A that used 111 50.45% of those Federal Money for Translator reporting Projects Total Number of Public Radio FM Translators in Appendix A that used 100 45.45% of those or rely on Local Fundraising for reporting Translator Projects WRVO, OSWEGO, NY Station Call Sign: WRVO Number of Main Stations: 4 Number of Translators: 11 cp’s not on air – 1 “frozen application” Call Signs and City of License of All Translators (attach list): W260BE Watertown NY W291BB Boonville NY W277BK Woodgate NY W261BB Steuben NY W237CC Rome NY W222AT Hamilton NY W293BE Norwich NY W241AW Geneva NY W238AT Cortlandville NY W237BJ Dryden NY W272BQ Marathon NY BNPFT-20030310BBB Ithaca NY (Pending) Estimated Population Served by All Translators: 65,000 Are any of your translators “daisy chained” (ie, one feeding another): yes How Many of Your Translators Serve Rural Communities: 9 How Many Translators Were Constructed with Federal Financial Assistance: PTFP Pending How Many Translators Were Constructed Pursuant to Local Fundraising Campaigns? All but Watertown were the result of grassroots campaigns. Watertown fills in a shadow in WRVJ’s null toward Canada. What factors prompted your decision to construct these translators? WRVO Page 2 In each case listeners had been using extraordinary means to receive WRVO or one of its class A relays. -

Fellow Broadcasters & Convention Attendees

The Alaska Broadcasters Association with Alaska Public Broadcasting Inc. PRESENTS The ABA/APBI 2019 Annual Convention November 14 & 15, 2019 With a special News Session on November 16 Sheraton Anchorage Hotel Please remember to thank our SPONSORS Lanyards Sponsor - Keynote Luncheon, Thursday 11/14/19 Buck Waters & Broadcasters General Store Thursday Afternoon Break 11/14/19 Friday Breakfast 11/15/19 Friday Break 11/15/19 Speaker Sponsor for Chris Lytle Attendee air fare discount: Message from the President Welcome to the 2019 Alaska Broadcasters Association Convention in Anchorage, Alaska. Our convention committee has worked hard to “Bring the World Together” with a program featuring motivational speakers, breakout sessions, and vendors that we hope will help you learn, grow and thrive in the broadcast industry – whether you’re in sales, management, news, programming, or engineering. Over the next several days, we encourage you to interact with your fellow broadcasters from around the state, share ideas, and visit with friends both old and new. Friday evening’s Goldie Awards Banquet will be our opportunity to celebrate the best of the best in Alaskan broadcasting, hosted by that dynamic duo from Fairbanks – Alaska Broadcaster Hall of Famers Glen Anderson and Jerry Evans. Who knows what fun they have in store for us this year! What we do as broadcasters truly matters and we could not do it as effectively without our association. The ABA’s mission is to provide assistance for our members through education, representation, and advocacy. We provide the Alternative Inspection Program, yearly Intern Grants, educational opportunities, and FCC updates. -

Appendix K: Mailing List

Appendix K Mailing List Appendix K: Mailing List K. Mailing List Alaska State Alaska Adventures Alaskan Perimeter Government Unlimited Expeditions Alaska Board of Fisheries Alaska Aerofuel Alaskan Sojourns Wilderness Guides Alaska Board of Game Alaska Air Taxi, LLC All About Adventure Alaska Bureau of Wildlife Alaska AirBoats LLC Alpine Outfitters Enforcement Alaska Alpine Adventures Alyeska Pipeline Service Alaska Department of Alaska Brooks Range Company Commerce, Community, Arctic Hunts and Economic Arctic Air Transport, Alaska Discovery Development LLC Alaska Flyers Alaska Department of Arctic Alaska Guide Fish and Game Alaska Ground Fish Data Service Bank Alaska Department of Arctic Getaway Law Alaska Heartland Arctic Power Inc. Alaska Department of Adventures Arctic River Journeys Natural Resources Alaska Mountain Alaska Department of Transport LLC Arctic Treks Transportation and Public Alaska River Adventures Arctic Wild Facilities Alaska River Expeditions Arctic Wilderness Lodge Alaska State Troopers & Flying Service Alaska Trophy Bering Straits Costal Connections Arrowhead Outfitters, Management Program LLC Alaska Trophy Safari's CENPA-CO-R-S Bear Lake Lodge Alaska Wilderness Office of the Governor Expeditions Beaver Sports State Historic Alaska Wilderness Big Game, Big Country Preservation Office Journeys Big Ray's Alaska Wilderness Big Wild Adventures Business, Industry Outfitting Co. Birch, Horton, Bittner & Alaska Wilderness 44 W Air Cherot Recreation and Tourism A.W. Enterprises Assoc. Bob Sevy Adventure Partners AAA Alaska Outfitters Alaska Wildtrek Inc. Branham Adventures Alaska-Denali Guiding ABEC's Alaska Inc. Bristol Bay Outfitters Adventures Alaskan Arctic Broken Point Fisheries Adams Guiding Service Expeditions Brooks Range Aviation Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Revised Comprehensive Conservation Plan K-1 Appendix K: Mailing List Bushcraft Guide Service Glacier Mountain Pro Engineering Outfitters Capitol Information Shadow Aviation Group H.C. -

Business Tax 990|Tax Return

(. 64((67,6( $: 0&+14$*( January 15, 2020= &DURO)DUULV= .$5-$7%.,& (.(&1//70,&$6,1050&= !0,8(45,6;4,8(= 0&+14$*( = ($4&DURO 0&.15('$4(6+()1..19,0*,0&1/(6$:4(6740524(2$4('10%(+$.)1)=.$5-$7%.,& (.(&1//70,&$6,100&)146+(;($4(0'('=70( (67401)4*$0,<$6,10:(/26)41/0&1/( $: ),.(,*0$674(76+14,<$6,1014/ &+('7.(7%.,&+$4,6;6$675$0'7%.,&722146 &+('7.(&+('7.(1)1064,%76145 &+('7.(1.,6,&$.$/2$,*0$0'1%%;,0*&6,8,6,(5 &+('7.(722.(/(06$.,0$0&,$.6$6(/(065 &+('7.(1/2(05$6,100)14/$6,10 &+('7.(722.(/(06$.0)14/$6,106114/14# &+('7.((.$6('4*$0,<$6,105$0'!04(.$6('$460(45+,25 +(5(4(674059(4(24(2$4(')41/,0)14/$6,102418,'('%;;1714;1744(24(5(06$6,8(= +( 24(2$4$6,101)6$:4(67405'1(5016,0&.7'(6+(,0'(2(0'(068(4,),&$6,101),0)14/$6,1075('= +(4()14(9(4(&1//(0';174(8,(96+(4(67405%()14(5,*0,0*61(0574(6+(4($4(011/,55,105 14/,556$6(/(065=);17016($0;6+,0*9+,&+/$;4(37,4($&+$0*(616+(4(674052.($5(&106$&6 75%()14(),.,0*6+(/ "($224(&,$6(6+,512214670,6;615(48(;17=.($5(&106$&675,);17+$8($0;37(56,10514,)9( /$;%(1))746+(4$55,56$0&( ,0&(4(.; $;;,4$9+$0,=, +, != IRS e-file Signature Authorization Form 8879-EO for an Exempt Organization OMB No.