Perceptions and Evaluations of University Principal Preparation Programs by Michigan Public School Principals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

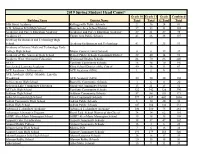

STATE LOCAL EDUCATION AGENCY (ENROLLMENTS > 1250) ENR. 504S RATE CONNECTICUT Newtown School District 4570 710 15.53% TEXAS

As a supplement to the corresponDing Zirkel analysis in the Educa'on Law Reporter, this compilaon, in DescenDing orDer of the percentage of 504-only stuDents, is baseD on the 2015-16 CRDC Data. To obtain the actual complete Data anD to request any correcbons, please go Directly to hdps://ocrData.eD.gov/ STATE LOCAL EDUCATION AGENCY (ENROLLMENTS > 1250) ENR. 504s RATE CONNECTICUT Newtown School District 4570 710 15.53% TEXAS Carrizo Springs Consol. InDep. School District 2254 325 14.41% CONNECTICUT Weston School District 2393 343 14.33% TEXAS Pittsburg InDep. School District 2472 335 13.55% TEXAS Pleasanton InDep. School District 3520 467 13.26% TEXAS Van Alstyne InDep. School District 1336 174 13.02% NEW JERSEY Hanover Park Regional High School District 1561 200 12.81% TEXAS Buna InDep. School District 1456 183 12.56% TEXAS Tatum InDep. School District 1687 208 12.32% TEXAS Crockett InDep. School District 1280 157 12.26% NEW YORK WinDsor Central School District 1697 208 12.25% TEXAS Hughes Springs InDep. School District 1266 153 12.08% TEXAS Pottsboro InDep. School District 4284 507 11.83% TEXAS Lake Dallas InDep. School District 3945 467 11.83% TEXAS NorthsiDe InDep. School District 105049 12425 11.82% TEXAS Kerrville InDep. School District 5038 592 11.75% TEXAS Gatesville InDep. School District 2853 335 11.74% TEXAS GoDley InDep. School District 1780 205 11.51% PENNSYLVANIA WallingforD-Swarthmore School District 3561 401 11.26% GEORGIA Wilkinson County Schools 1523 169 11.09% LOUISIANA Terrebonne Parish School District 18445 2039 11.05% NEW YORK Briarcliff Manor Union Free School District 1469 162 11.02% WASHINGTON Mercer IslanD School District 4423 485 10.96% TEXAS Community InDep. -

Michigan Department of Education Indirect Cost Rates for Special Education Added Costs, Year 2018-2019 District Code: 01010 Report R0416

Michigan Department of Education Indirect Cost Rates for Special Education Added Costs, Year 2018-2019 District Code: 01010 Report R0416 Alcona Community Schools P.O. Box 249 Lincoln, MI 48742 Indirect Costs (Operations & Maintenance): General Fund 720,059.52 Less: Capital Outlay 5,823.86 Special Education Fund 0.00 Less: Capital Outlay 0.00 School Lunch Fund 0.00 Less: Capital Outlay 0.00 Total Indirect (less Capital) 714,235.66 Direct Costs: General Fund 7,404,605.03 Less: Capital Outlay 137,372.70 Less: Facilities Acquisition 87,223.14 Special Education Fund 0.00 Less: Capital Outlay 0.00 Less: Facilities Acquisition 0.00 School Lunch Fund 0.00 Less: Capital Outlay 0.00 Less: Facilities Acquisition 0.00 Total Direct (less Capital) 7,180,009.19 Special Education Indirect Cost Rate: 9.95% (If computed rate exceeds maximum allowable of 15.00%, 15.00% is used) SAMS/FIDReports/IndirectSpecialEdCosts.rdl 4/16/2019 Michigan Department of Education Indirect Cost Rates for Special Education Added Costs, Year 2018-2019 District Code: 02010 Report R0416 AuTrain-Onota Public Schools P.O. Box 105 Deerton, MI 49822 Indirect Costs (Operations & Maintenance): General Fund 69,629.04 Less: Capital Outlay 0.00 Special Education Fund 0.00 Less: Capital Outlay 0.00 School Lunch Fund 825.49 Less: Capital Outlay 0.00 Total Indirect (less Capital) 70,454.53 Direct Costs: General Fund 893,639.88 Less: Capital Outlay 26,604.97 Less: Facilities Acquisition 4,695.63 Special Education Fund 0.00 Less: Capital Outlay 0.00 Less: Facilities Acquisition 0.00 School Lunch Fund 46,744.56 Less: Capital Outlay 0.00 Less: Facilities Acquisition 0.00 Total Direct (less Capital) 909,083.84 Special Education Indirect Cost Rate: 7.75% (If computed rate exceeds maximum allowable of 15.00%, 15.00% is used) SAMS/FIDReports/IndirectSpecialEdCosts.rdl 4/16/2019 Michigan Department of Education Indirect Cost Rates for Special Education Added Costs, Year 2018-2019 District Code: 02020 Report R0416 Burt Township School District P.O. -

Annual Report for 2018-19

IMPROVING LEARNING. IMPROVING LIVES. MICHIGAN VIRTUAL UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT: 2018-19 Table of Contents About Michigan Virtual ................................................................................................................... 2 Student Learning ............................................................................................................................ 3 Student Online Learning in Michigan ...................................................................................................... 3 Michigan Virtual Student Learning Fast Facts for 2018-19 .................................................................. 4 Students .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Districts ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Courses ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Pass Rates ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Current Initiatives ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Professional Learning ................................................................................................................... -

2019 Spring Student Head Count*

2019 Spring Student Head Count* Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade Combined Building Name District Name Total Total 12 Total Total 54th Street Academy Kelloggsville Public Schools 21 36 24 81 A.D. Johnston Jr/Sr High School Bessemer Area School District 39 33 31 103 Academic and Career Education Academy Academic and Career Education Academy 27 21 27 75 Academy 21 Center Line Public Schools 43 26 38 107 Academy for Business and Technology High School Academy for Business and Technology 41 17 35 93 Academy of Science Math and Technology Early College High School Mason County Central Schools 0 0 39 39 Academy of The Americas High School Detroit Public Schools Community District 39 40 14 93 Academy West Alternative Education Westwood Heights Schools 84 70 86 240 ACCE Ypsilanti Community Schools 28 48 70 146 Accelerated Learning Academy Flint, School District of the City of 40 16 11 67 ACE Academy - Jefferson site ACE Academy (SDA) 1 2 0 3 ACE Academy (SDA) -Glendale, Lincoln, Woodward ACE Academy (SDA) 50 50 30 130 Achievement High School Roseville Community Schools 3 6 11 20 Ackerson Lake Community Education Napoleon Community Schools 15 21 15 51 ACTech High School Ypsilanti Community Schools 122 142 126 390 Addison High School Addison Community Schools 57 54 60 171 Adlai Stevenson High School Utica Community Schools 597 637 602 1836 Adrian Community High School Adrian Public Schools 6 10 20 36 Adrian High School Adrian Public Schools 187 184 180 551 Advanced Technology Academy Advanced Technology Academy 106 100 75 281 Advantage Alternative Program -

MONROE COUNTY Schools of Choice ENROLLMENT PERIOD APRIL 1, 2021 - JUNE 25, 2021 ONLY

MONROE COUNTY Schools of Choice ENROLLMENT PERIOD APRIL 1, 2021 - JUNE 25, 2021 ONLY 2021-2022 Guidelines and Application What Parents Graduation/ and Guardians Step-By-Step Promotion Transportation and Timeline of the Important Dates Need to Know: Requirements and Information for The Schools Athletic Policies Application and Curriculum Process Parents of Choice Issues Application Process Deadlines TO REMEMBER To provide a quality education for all students in Monroe County, the Monroe County Schools of Choice STEP 1: Due June 25, 2021 Program is offered by the Monroe County Intermediate Application must be returned to the School District in cooperation with its constituent administration building of the resident districts. This program allows parents and students the district. choice to attend any public school in Monroe County, as STEP 2: July 9, 2021 determined by space available. Applicants are notified to inform them whether they have been accepted into Remember, a student must be released by his/her the Schools of Choice Program. resident district and be accepted by the choice district before he/she can enroll at the choice district. The STEP 3: August 6, 2021 Parents/guardians must formally accept student will not be able to start school unless ALL or reject acceptance into the Schools of paperwork is completed BEFORE THE START OF Choice Program. SCHOOL. The student must be formally registered at the choice district by Friday, August 13, 2021. STEP 4: August 13, 2021 Student must be formally registered at the choice school. The Schools of Choice Application Process WHAT PARENTS AND GUARDIANS NEED TO KNOW The application process for the • Students participating in this program • An application form must be completed Monroe County Schools of Choice who wish to return to their resident for each student wishing to participate school for the following year, must notify Program has been designed to the resident school district as soon in the choice program. -

COVID Relief 75-25 Full Data BD.Xlsx

Michigan School District: Extra COVID Funds Breakdown District District (1) FEDERAL COVID (2) STATE FORMULA: 75- COVID Relief: CARES COVID Relief: ESSER Code Type District Name RELIEF Per Pupil 25 IMPACT Per Pupil ACT COVID Relief: ESSER II III 01010 LEA Alcona Community Schools $3,428,818.24 $5,195.18 $72,269.01 $109.50 $344,479.24 $949,771.00 $2,134,568.00 02010 LEA AuTrain-Onota Public Schools $250,407.99 $10,887.30 $17,584.56 $764.55 $26,485.99 $68,953.00 $154,969.00 02020 LEA Burt Township School District $24,268.17 $808.94 $1,564.05 $52.14 $9,954.17 $4,408.00 $9,906.00 02070 LEA Munising Public Schools $1,706,250.46 $2,877.32 $79,812.24 $134.59 $255,846.46 $446,628.00 $1,003,776.00 02080 LEA Superior Central School District $710,011.80 $2,297.77 $37,878.37 $122.58 $134,632.80 $177,179.00 $398,200.00 03010 LEA Plainwell Community Schools $4,213,754.82 $1,593.70 $905,349.82 $342.42 $755,800.82 $1,064,819.00 $2,393,135.00 03020 LEA Otsego Public Schools $3,435,751.05 $1,523.61 $393,302.39 $174.41 $604,677.05 $871,782.00 $1,959,292.00 03030 LEA Allegan Public Schools $6,466,858.21 $2,927.50 $1,345,452.68 $609.08 $896,281.21 $1,715,367.00 $3,855,210.00 03040 LEA Wayland Union Schools $4,229,061.97 $1,452.29 $771,923.87 $265.08 $771,107.97 $1,064,819.00 $2,393,135.00 03050 LEA Fennville Public Schools $4,450,305.03 $3,404.98 $45,097.16 $34.50 $649,021.03 $1,170,542.00 $2,630,742.00 03060 LEA Martin Public Schools $1,433,212.85 $2,315.37 $0.00 $0.00 $219,894.85 $373,622.00 $839,696.00 03070 LEA Hopkins Public Schools $1,709,034.23 $1,110.48 -

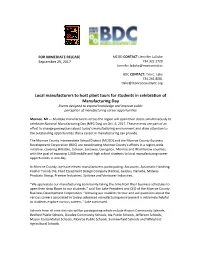

Joint Press Release for 2017 Event

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MCISD CONTACT: Jennifer LaDuke September 29, 2017 734.322.2720 [email protected] BDC CONTACT: Tim C. Lake 734.241.8081 [email protected] Local manufacturers to host plant tours for students in celebration of Manufacturing Day Events designed to expand knowledge and improve public perception of manufacturing career opportunities Monroe. MI — Multiple manufacturers across the region will open their doors simultaneously to celebrate National Manufacturing Day (MFG Day) on Oct. 6, 2017. These events are part of an effort to change perceptions about today’s manufacturing environment and draw attention to the outstanding opportunities that a career in manufacturing can provide. The Monroe County Intermediate School District (MCISD) and the Monroe County Business Development Corporation (BDC) are coordinating Monroe County’s efforts in a region-wide initiative, covering Hillsdale, Jackson, Lenawee, Livingston, Monroe and Washtenaw counties, with the goal of exposing 1,000 middle and high school students to local manufacturing career opportunities in one day. In Monroe County, we have eleven manufacturers participating: Accuworx, Automatic Handling, Fischer Tool & Die, Fluid Equipment Design Company (Fedco), Gerdau, Hanwha, Midway Products Group, Premier Industries, Spiratex and Ventower Industries. “We appreciate our manufacturing community taking the time from their business schedules to open their shop floors to our students,” said Tim Lake President and CEO of the Monroe County Business Development Corporation. “Allowing our students to tour and ask questions about the various careers associated in todays advanced manufacturing environment is extremely helpful as students explore various careers,” Lake continued. Schools from all nine districts will be participating which include Airport Community Schools, Bedford Public Schools, Dundee Community Schools, Ida Public Schools, Jefferson Schools, Mason Consolidated Schools, Monroe Public Schools, Summerfield Schools and Whiteford Agricultural Schools. -

Fiscal Year 2019 Title I Grants to Local Educational Agencies

Fiscal Year 2019 Title I Grants to Local Educational Agencies - MICHIGAN No data No data No data LEA ID District FY 2019 Title I Allocation 2601890 Adams Township School District 48,702 2601920 Addison Community Schools 176,777 2601950 Adrian City School District 1,065,733 2601980 Airport Community School District 592,071 2602010 Akron-Fairgrove Schools 109,502 2621810 Alanson Public Schools 122,097 2602040 Alba Public Schools 54,249 2602160 Alcona Community Schools 294,838 2602190 Algonac Community School District 320,379 2602220 Allegan Public Schools 500,720 2602520 Allen Park Public Schools 302,176 2602550 Allendale Public School District 199,237 2602640 Alma Public Schools 638,109 2602670 Almont Community Schools 106,882 2602730 Alpena Public Schools 1,090,796 2602790 Anchor Bay School District 444,963 2602820 Ann Arbor Public Schools 1,992,536 2603060 Arenac Eastern School District 145,018 2603240 Armada Area Schools 52,311 2603270 Arvon Township School District 0 2603480 Ashley Community Schools 81,924 2603510 Athens Area Schools 187,809 2603540 Atherton Community Schools 343,521 2603570 Atlanta Community Schools 150,532 2603600 Au Gres-Sims School District 142,341 2603660 Autrain-Onota Public Schools 28,736 2603690 Avondale School District 291,470 2600017 Bad Axe Public Schools 272,994 2603810 Baldwin Community Schools 718,564 2603870 Bangor Public Schools 455,527 2603960 Bangor Township School District 8 14,476 2603900 Bangor Township Schools 515,938 2603990 Baraga Area Schools 129,234 2604020 Bark River-Harris School District -

2013 SCF Annual Report.Pdf

OUR MISSION The Saginaw Community Foundation has one mission: 4 to come to life, now and forever. We accomplish our mission by: *strategic leadership in our community *endowment *grantmaking *Stewardship4 CONTENTS Year-in-Review 4 Scholarly Impact 16 2013 Contributors 22 Community Impact 6 Volunteers 18 Current Funds 26 ! Inner Circle Sponsors 19 )*%+ )! Our Youth, Our Future 10 ' %( #/ +* A Vision to Steer the Future 12 Financial Report 20 Committee Members 31 Making an Impact with Force 14 Investment Strategy 21 Foundation Staff 31 "#$ %& 57;<<5= This annual report was written and designed in-house at Saginaw Community Foundation. Developmental Assets is a registered trademark of Search Institute. There is no doubt about it – the Saginaw Community Foundation (SCF) < is the SCF 2013 annual report so focused on that impact? Well, maybe because it’s how we made or accomplished that impact in 2013. Let us explain. "5=#/ to participate in a strategic planning process. The purpose for the process was to create a master plan for the delivery of foundation services and making an impact. As we began the planning process, we discovered that we could be doing a better job of communicating our impact to the community. That discussion led to a complete revision of our mission statement, which can be found on the opposite page. RENEÉ S. JOHNSTON The 2013 annual report shares some great stories on how we put the <(# to life” – such as building equity and fairness in local foods systems /;#$DEG<HJ$ kids about employability through the Jump Start program (see page 7). Through the leadership SCF can offer or the grants we award, we have positioned ourselves to work with organizations, individuals, governmental entities or groups of volunteers, to assist with projects and programs so they can have a positive impact on the community. -

School Bus Inspection Report for School Year 2014/2015

School Bus Inspection Report for School Year 2014/2015 1-SEP-2014 to 31-MAY-2015 DISTRICT NAME PASS YELLOW RED TOTAL Academy for Business and Technology 3 0 0 3 Ada Christian School 3 0 1 4 Adams Township School District 2 0 2 4 Addison Community Schools 10 1 0 11 Adrian, School District of the City of 26 1 0 27 Airport Community Schools 21 1 1 23 Akron-Fairgrove Schools 1 1 4 6 Alanson Public Schools 4 0 0 4 Alba Public Schools 3 0 0 3 Albion Public Schools 8 0 0 8 Alcona Community Schools 15 0 0 15 Algoma Christian School 0 1 2 3 Algonac Community School District 15 0 1 16 Allegan Area Educational Service Agency 25 1 0 26 Allegan Public Schools 22 5 1 28 School Bus Inspection Report for School Year 2014/2015 1-SEP-2014 to 31-MAY-2015 DISTRICT NAME PASS YELLOW RED TOTAL Allen Park Public Schools 2 0 0 2 Allendale Christian School 0 0 2 2 Alma Public Schools 5 3 9 17 Almont Community Schools 14 1 2 17 Alpena Public Schools 36 2 3 41 Anchor Bay School District 44 1 2 47 Ann Arbor Public Schools 108 0 0 108 Arvon Township School District 2 0 0 2 Ashley Community Schools 1 0 5 6 Atherton Community Schools 7 0 0 7 Atlanta Community Schools 4 0 1 5 Au Gres-Sims School District 1 0 0 1 AuTrain-Onota Public Schools 1 0 0 1 Bad Axe Public Schools 1 0 0 1 Bangor Public Schools (Van Buren) 12 1 1 14 Bangor Township Schools 16 4 3 23 School Bus Inspection Report for School Year 2014/2015 1-SEP-2014 to 31-MAY-2015 DISTRICT NAME PASS YELLOW RED TOTAL Baraga Area Schools 6 0 1 7 Bark River-Harris School District 8 0 3 11 Bath Community Schools 6 1 -

SAMS/Fidreports/Indirectratessummary.Rdl Page 1 / 22 Michigan Department of Education Local District Indirect Cost Rates

*** Final *** Michigan Department of Education *** Final *** Local District Indirect Cost Rates for School Year 2018-2019 Based on 2016-2017 Costs R0418 Rate Summary Report * * ** District Restricted Unrestricted Medicaid Code District Name Rate Rate Rate 01010 Alcona Community Schools 6.45 17.03 17.03 02010 AuTrain-Onota Public Schools 12.60 21.95 21.95 02020 Burt Township School District 3.81 20.22 20.22 02070 Munising Public Schools 5.02 18.36 19.23 02080 Superior Central School District 4.67 13.99 12.65 03000 Allegan Area Educational Service Agency 11.75 23.05 26.06 03010 Plainwell Community Schools 2.34 14.74 13.86 03020 Otsego Public Schools 2.65 14.73 13.60 03030 Allegan Public Schools 1.80 12.37 12.36 03040 Wayland Union Schools 3.80 15.38 15.37 03050 Fennville Public Schools 3.78 22.90 22.63 03060 Martin Public Schools 5.37 18.99 19.36 03070 Hopkins Public Schools 3.96 16.78 14.02 03080 Saugatuck Public Schools 5.29 13.66 13.66 03100 Hamilton Community Schools 1.56 8.77 8.77 03440 Glenn Public School District 9.90 64.11 63.24 03902 Outlook Academy 3.55 7.24 7.24 04000 Alpena-Montmorency-Alcona ESD 15.63 15.17 15.17 04010 Alpena Public Schools 3.32 15.15 13.81 05010 Alba Public Schools 4.95 19.27 17.30 05035 Central Lake Public Schools 0.00 12.26 12.26 05040 Bellaire Public Schools 2.85 18.43 17.61 05060 Elk Rapids Schools 3.35 12.50 12.50 05065 Ellsworth Community School 2.31 8.33 8.33 05070 Mancelona Public Schools 4.47 17.50 19.63 06010 Arenac Eastern School District 2.26 19.18 21.61 06020 Au Gres-Sims School District 3.03 14.08 -

SAF Loss from Tax Refund Shift DISTRICT BREAKDOWNS 2018

What Losing $180m Means For School Districts - By Senate District NOTE: School districts cuts are counted in full in each SD where all or part of the school district lies (i.e., School districts are counted in multiple SDs) Based on projected $180m loss to SAF - broken down to $121.47 per pupil x number of students Row Labels Sum of Loss Based on 2017-18 Pupil Count 1 $9,045,806.71 Ecorse Public School District $124,779.82 Gibraltar School District $448,115.82 Grosse Ile Township Schools $223,375.87 River Rouge School District $260,890.22 Riverview Community School District $352,167.79 Trenton Public Schools $308,668.68 Woodhaven-Brownstown School District $649,729.38 Wyandotte City School District $579,035.88 Detroit Public Schools Community District $6,099,043.26 2 $7,689,360.97 Grosse Pointe Public Schools $951,103.87 Hamtramck Public Schools $399,621.92 Harper Woods Schools, City of $239,591.92 Detroit Public Schools Community District $6,099,043.26 3 $9,007,842.92 Dearborn City School District $2,540,081.78 Melvindale-North Allen Park Schools $368,717.89 Detroit Public Schools Community District $6,099,043.26 4 $7,604,788.47 Allen Park Public Schools $464,955.01 Lincoln Park Public Schools $593,217.34 Southgate Community School District $447,572.86 Detroit Public Schools Community District $6,099,043.26 5 $10,573,169.69 Crestwood School District $507,843.14 Dearborn Heights School District #7 $305,894.33 Garden City School District $460,658.67 Redford Union School District $384,167.47 South Redford School District $463,484.03 Taylor