Exhibit “I” to the Statement of Evidence of Marilyn Gabriel Chief of Kwantlen First Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experience the Fraser Concept Plan Overview

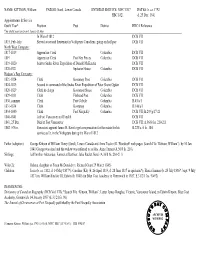

City of Report to Committee Richmond inR4:s -dvy,g_2 -\::? ;?i)t2- To: Parks, Recreation and Cultural Services Date: May 31 , 2012 Committee From: Dave Semple File: 06-2400-01/201 2-Vol General Manager, Parks and Recreation 01 Re: Experience the fraser Concept Plan Overview Staff Recommendation Then the Experience the Fraser: Lower Fraser River Corridor Project Concept Plan as described in attachment 1 of the report, Experience the Fraser Concept Plan Overview, dated May 22nd 2012 from the General Manager, Parks and Recreation, be endorsed as a regionally beneficial initiative. ave ern Ie ral Manager, Parks and Recreation (604-233-3350) Au. 1 REPORT CONCURRENCE ROUTED TO: CONCURRENCE CONCURRENCE OF G ENERAL MANAGER Arts, Culture & Heritage ~ ~~ / REVIEWED BY TAG INITIALS: REVI E~ AO SUBCOMMITIEE ~ m 3~ 4 S%2 CNCL - 45 ___-' M"'ay--1L 2012 - 2 - Staff Report Origin The Experience the Fraser (ETF) project is a Provincial Government initiative to raise awareness and showcase the rich recreational, cultural and natural heritage of the Lower Fraser Corridor from Hope to the Salish Sea. In 2009, Metro Vancouver and the Fraser Vall ey Regional District rece ived $2.0 million to develop a comprehensive plan for a continuous recreational corridor on both sides ofthe main river - the south ann of the Fraser. City staff have provided input into this concept plan by meeting with regional staff, attending workshops, and providing background information from the City's many existing strategic plans and documents. A draft concept plan has now been completed and was endorsed in principle by both the Metro Vancouver and Fraser Valley Regional District Boards in October 20 11. -

The Native Land Policies of Governor James Douglas

The Native Land Policies of Governor James Douglas Cole Harris* n British Columbia, as in other settler colonies, it was in the interest of capital, labour, and settlers to obtain unimpeded access to Iland. The power to do so lay in the state’s military apparatus and in an array of competences that enabled it to manage people and distance. Justification for the dispossession of Native peoples was provided by assumptions about the benefits of civilizing savages and of turning wasteful land uses into productive ones. Colonization depended on this combination of interest, power, and cultural judgment. In British Columbia, approximately a third of 1 percent of the land of the province was set aside in Native reserves. The first of these reserves were laid out on Vancouver Island in the 1850s, and the last, to all intents and purposes, during the First World War. Not all government officials thought them sufficient, and during these years there were two sustained attempts to provide larger Native reserves. The first, in the early 1860s, was associated with Governor James Douglas, and the second, in the late 1870s, with Gilbert Malcolm Sproat, an Indian reserve commis- sioner who knew Douglas and admired and emulated his Native land policies. Both attempts, however, were quickly superseded. Douglas resigned in April 1864. His Native land policies were discontinued and some of his reserves were reduced. Sproat resigned in March 1880, and over the next almost twenty years his successor, Peter O’Reilly, allocated the small reserves that the government and settler opinion demanded. The provincial government, which by the 1880s controlled provincial * Editors' note: This is a necessarily verbatim version of Cole Harris's deposition as an expert witness in a forthcoming land claims case. -

Building of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails Researched and Written by Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, June 2010; Updated Dec 2012 and Dec 2013

Early Trail Building in the New Colony of British Columbia — John Hall’s Building of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails Researched and written by Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, June 2010; updated Dec 2012 and Dec 2013. A recent “find” of colonial correspondence in the British Columbia Archives tells a story about the construction of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails between 1862 and 1864 by pioneer settler John Hall. (In 1870 Hall pre-empted 160 acres of Crown Land on Indian Arm and became Belcarra’s first European settler.) The correspondence involves a veritable “who’s who” of people in the administration in the young ‘Colony of British Columbia’. This historic account serves to highlight one of the many challenges faced by our pioneers during the period of colonial settlement in British Columbia. Sir James Douglas When the Fraser River Gold Rush began in the spring of 1858, there were only about 250 to 300 Europeans living in the Fraser Valley. The gold rush brought on the order of 30,000 miners flocking to the area in the quest for riches, many of whom came north from the California gold fields. As a result, the British Colonial office declared a new Crown colony on the mainland called ‘British Columbia’ and appointed Sir James Douglas as the first Governor. (1) The colony was first proclaimed at Fort Langley on 19th November, 1858, but in early 1859 the capital was moved to the planned settlement called ‘New Westminster’, Sir James Douglas strategically located on the northern banks of the Fraser River. -

The Implications of the Delgamuukw Decision on the Douglas Treaties"

James Douglas meet Delgamuukw "The implications of the Delgamuukw decision on the Douglas Treaties" The latest decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Delgamuukw vs. The Queen, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010, has shed new light on aboriginal title and its relationship to treaties. The issue of aboriginal title has been of particular importance in British Columbia. The question of who owns British Columbia has been the topic of dispute since the arrival and settlement by Europeans. Unlike other parts of Canada, few treaties have been negotiated with the majority of First Nations. With the exception of treaty 8 in the extreme northeast corner of the province, the only other treaties are the 14 entered into by James Douglas, dealing with small tracts of land on Vancouver Island. Following these treaties, the Province of British Columbia developed a policy that in effect did not recognize aboriginal title or alternatively assumed that it had been extinguished, resulting in no further treaties being negotiated1. This continued to be the policy until 1990 when British Columbia agreed to enter into the treaty negotiation process, and the B.C. Treaty Commission was developed. The Nisga Treaty is the first treaty to be negotiated since the Douglas Treaties. This paper intends to explore the Douglas Treaties and the implications of the Delgamuukw decision on these. What assistance does Delgamuukw provide in determining what lands are subject to aboriginal title? What aboriginal title lands did the Douglas people give up in the treaty process? What, if any, aboriginal title land has survived the treaty process? 1 Joseph Trutch, Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works and Walter Moberly, Assistant Surveyor- General, initiated this policy. -

HBCA Biographical Sheet

NAME: KITTSON, William PARISH: Sorel, Lower Canada ENTERED SERVICE: NWC 1817 DATES: b. ca. 1792 HBC 1821 d. 25 Dec. 1841 Appointments & Service Outfit Year* Position Post District HBCA Reference *An Outfit year ran from 1 June to 31 May In War of 1812 DCB VII 1815, Feb.-July Served as second lieutenant in Voltigeurs Canadiens, going on half-pay DCB VII North West Company: 1817-1819 Apprentice Clerk Columbia DCB VII 1819 Apprentice Clerk Fort Nez Perces Columbia DCB VII 1819-1820 Sent to Snake River Expedition of Donald McKenzie DCB VII 1820-1821 Spokane House Columbia DCB VII Hudson’s Bay Company: 1821-1824 Clerk Kootenay Post Columbia DCB VII 1824-1825 Second in command of the Snake River Expedition of Peter Skene Ogden DCB VII 1826-1829 Clerk in charge Kootenae House Columbia DCB VII 1829-1831 Clerk Flathead Post Columbia DCB VII 1830, summer Clerk Fort Colvile Columbia B.45/a/1 1831-1834 Clerk Kootenay Columbia B.146/a/1 1834-1840 Clerk Fort Nisqually Columbia DCB VII; B.239/g/17-21 1840-1841 At Fort Vancouver in ill health DCB VII 1841, 25 Dec. Died at Fort Vancouver DCB VII; A.36/8 fos. 210-211 1842, 5 Nov. Executors appoint James H. Kerr to get compensation for the estate for his B.223/z /4 fo. 184 service as Lt. in the Voltigeurs during the War of 1812 Father (adoptive): George Kittson of William Henry (Sorel), Lower Canada and Anne Tucker (R. Woodruff web pages; Search File “Kittson, William”); by 10 Jan. -

Sir James Douglas and British Columbia. by WALTER N. SAGE. (Toronto: the University of Toronto Press, 1930

BOOK REVIEWS Sir James Douglas and British Columbia. By WALTER N. SAGE. (Toronto: The University of Toronto Press, 1930. Pp. 308.) This study of the life and times of Sir James Douglas, which is a thesis for a doctorate, is the first attempt to deal with him as a man rather than an administrator. It is proverbially difficult to separate the man from the official. The earlier lives and sketches of Douglas's career have buried the man under his work-have treated him merely as a peg on which to hang forty years of Pacific Coast history. Our author settles definitely the date and place of Douglas's birth as being June 5, 1803, in Lanarkshire, Scotland, and not, as has been'frequently stated, August 14, 1803 in either British Guiam or Jamaica. He shows us the little Douglas attending school in Lanark, and, later, as a boy in his teens sailing for Canada to enter the service of the North West Company. There is a great paucity of biographical material for the first sixteen years (1819-1835) of Douglas's life in les pays d'en haut. All that can at present be found has been carefully sought out, brought together, and pieced out with tradition or family report, gathered from the lips of his descendants. It is doubtful if the in formation given by Dr. Sage or his conclusions thereon will ever be materially altered or supplemented, unless contemporary records of the two companies or letters of his early associates come to light a possibility of annually diminishing probability. -

Brae Island Regional Park Managament Plan

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS During the process of creating the Brae Island Regional Park Management Plan, many outside organizations, agencies and individuals provided perspectives and expertise. We recognize the contribution of representatives from the Fort Langley Community Association, Fort Langley Business Improvement Association, Langley Heritage Society, Langley Field Naturalists, Fort Langley Canoe Club, BC Farm Machinery and Agriculture Museum, Langley Centennial Museum and National Exhibition Centre, Greater Langley Chamber of Commerce, Equitas Developments, Wesgroup, Kwantlen First Nation, Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Agricultural Land Commission, Parks Canada, and especially, the Township of Langley. Thanks also go to our consultants including: Phillips Farevaag Smallenberg Landscape Architects, Strix Environmental Consultants, Northwest Hydraulics Consulting, GP Rollo & Associates, Tumia Knott of Kwantlen First Nation and Doug Crapo. Special thanks go out to: Board members from the Derby Reach/Brae Island Regional Park – Park Association; and Stan Duckworth, operator of Fort Camping. We also remember Don McTavish who saw the potential of creating a camping experience on Brae Island. While many GVRD staff from its Head and East Area Offices assisted this planning process special mention should go to the planning and research staff, Will McKenna, Janice Jarvis and Heather Wornell. Finally, we wish to thank all of those members of the public who regularly attended meetings and contributed their valuable time and insights to the Plan. Wendy DaDalt GVRD Parks Area Manager East Area TABLE OF CONTENTS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER OF CONVEYANCE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................................. 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION................................................................................ 3 1.1 Brae Island Regional Park and the GVRD Parks and Greenways System....................................... -

Smallpox and Identity Reformation Among the Coast Salish Keith Thor Carlson

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 02:56 Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada Precedent and the Aboriginal Response to Global Incursions: Smallpox and Identity Reformation Among the Coast Salish Keith Thor Carlson Global Histories Résumé de l'article Histoires mondiales Les réactions des Autochtones par rapport à la mondialisation ont été variées Volume 18, numéro 2, 2007 et complexes. Cette communication examine une expression particulière de l’internationalisme (épidémies au sein de la Première nation Coast Salish du URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/018228ar sud-ouest de la C.-B. et nord-ouest de l’État Washington par suite du contact DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/018228ar avec les Européens) et le situe dans le contexte des premières catastrophes régionales telles que comprises aux moyens des légendes. De cette façon, l’article recadre un des paradigmes d’interprétation standard du domaine – à Aller au sommaire du numéro l’effet que les épidémies étaient sans précédent et qu’elles représentaient peut-être la plus importante « rupture » de l’histoire autochtone. L’article montre les façons dont les communautés et les membres de la Première nation Éditeur(s) Coast Salish ont affronté les désastres. Il conclut que les histoires anciennes fournissaient au peuple des précédents qui façonnaient ensuite sa réaction à The Canadian Historical Association/La Société historique du Canada l’internationalisme. L’article illustre comment les historiens peuvent puiser dans les façons de raconter des Autochtones, dans lesquelles les généalogies, ISSN les légendes mythiques et les endroits spécifiques jouent des rôles cruciaux. -

The Fort Victoria Treaties

The Fort Victoria Treaties WILSON DUFF This essay had a simple purpose when it was begun : to publish a list of the Indian place names of the Victoria area which Songhees friends had told me about from time to time since 1952. It has grown, in the course of writing, into something more complicated than that. The rechecking of the names and their meanings gave opportunities to revisit old friends, and to learn more names and more of the Songhees history associated with them. It also led to the rediscovery of some of the earlier ethno graphic and historical records, and to a conviction that these now need to be better known. Of the ethnographic records the most commendable are the field notes and yet-unpublished thesis of Dr. Wayne Suttles ( 1951 ). Of the historical documents, those which above all seem worthy of renewed recognition are the eleven Fort Victoria treaties of 1850 and 1852, by which James Douglas of the Hudson's Bay Company extin guished the Indian title to the lands between Sooke and Saanich. An identical treaty which he made at Nanaimo in 1854 has recently been judged by the Supreme Court of Canada to be still in effect, and so by implication these untidy and almost-unknown little documents have been reconfirmed in their full status as treaties. A place name is a reminder of history, indelibly stamped on the land. To enquire about it is to reawaken memories of the history that produced it. To write about it is to retell some of that history. -

1 Between 1860 and 1870 First Nations in British Columbia Still

DEFINING THE WHONNOCK RESERVE Between 1860 and 1870 First Nations in British Columbia still largely outnumbered the European and other immigrants but a steadily growing number of newcomers, claiming large sections of land, increasingly put pressure on the original Native users of its resources. In some parts of the province open hostilities grew between First Nations and the settlers. Setting aside “Indian lands” or reserves was a way to avoid disputes. To satisfy the white settlers, members of the Columbia Detachment of the Royal Engineers under direction of Colonel Richard Moody started to define and mark out reserves in the Lower Mainland, including one of about 90 acres for the Whonnock Tribe. In 1864, the year of his retirement, Governor Douglas, having the interest of the Native population foremost in mind, instructed the former Royal Engineer William McColl to mark out Indian reserves on the Fraser River between New Westminster and the Harrison River leaving “...the extent and selection entirely optional with the Indians who were immediately interested in the reserve [and] to include every piece of ground to which to which they had acquired an equitable title through continued occupation.”1 Accordingly McColl defined large areas of land for the Native villages in areas where there were only a few or no pre-emptions by white settlers. The largest such area was for the Matsquee (Matsqui) Tribe with 9,600 acres. In comparison the 2,000 acres set aside for the Whonnock Tribe and the 500 acres for the Saan-oquâ village across the Fraser in what is now known as Glen Valley seemed small, but it was enormous when compared with the original 90-acre reserve laid out by the Royal Engineers. -

Kanaka World Travelers and Fur Company Employees, 1785-1860

Kanaka World Travelers and Fur Company Employees, 1785-1860 Janice K. Duncan Chinese, Japanese, and Negroes were not the only minority racial groups represented in the early history of Oregon Country (which included Oregon, Washington, parts of Idaho and Montana). Before approximately i860 many foreigners in the area were Hawaiian Islanders, called Sandwich Islanders, Owhyees and, most frequently, Kanakas. Hawaii was discovered in 1778 by Captain James Cook, who named the islands after his patron, the Earl of Sandwich. Within less than a decade after Cook's discovery the Islands had become a regular stop for merchant and whaling vessels needing fresh water and provisions, and many crew members remained in the newly discovered paradise.1 Cook's discovery also brought the natives of Hawaii a new outlet for their curiosity and for their excellent abilities on the sea. The ships that stopped in the Islands often were looking for additions to their crews, either as seamen or as personal servants for the officers or for the wives of merchant captains who often accompanied their husbands.2 In May 1787, the British ship Imperial Eagle took aboard an Hawaiian woman, to be the personal servant of the captain's wife, and she became the first recorded Islander to leave her homeland.3 In China the captain's wife decided to travel on to Europe, and Winee was left behind to return to the Islands. She found passage on the Nootka, then in the China Sea, and met an Hawaiian chief, Kaiona (Tianna), who had agreed to accom- pany John Meares aboard the Nootka when it left the Islands in August 1787.* There were two other Kanakas who boarded the Nootka with Winee. -

Year in Review

YEAR IN REVIEW 2020 (JULY 01, 2019 – JUNE 30, 2020) Registered Society # 810236273 RR0001 #1 45950 Cheam Avenue., Chilliwack BC V2P 1N6 fvwc.ca | 604-791-2235 Cover Photo: Downstream view of the Bedford Channel at low-low tide inspecting rootwads. at dawn 2020, MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR This past year, 2020, has challenged most of us, like no other year in living memory, and the Fraser Valley Watersheds Coalition was no exception. We have discovered a simple truth that sure, we thought about, but this year made us live it. That being, what makes an organization truly good, are the people that care and contribute, our staff, our supporters and our partners. Our staff have been exemplary in following strategies to keep themselves and the broader community healthy during this COVID year. Our supporters got us through our Annual General Meeting with a Zoom and a smile and maybe a laugh or two as we followed our health leader’s advice on how to stay safe while socially distant gathering. Our partners found creative ways to keep funds flowing and, on the ground, projects moving ahead, even under difficult circumstances, giving true meaning to that old quote “Strength through Adversity.” Just going fishing is a culturally important activity here in the Fraser River but the drive and creativity of certain supporters have turned this simple act into the “Wally Hall Jr. Memorial Steelhead Derby” which has raised much cherished funds for the FVWC works in the Chilliwack-River watershed, well done, thank you and tight lines to you all.