Edited by Miranda Lash & Trevor Schoonmaker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPM-Catalog-Fall-2020.Pdf

N I V E R S I U T Y P R E S S O Books for Fall–Winter 2020–2021 F M I I S P S P I I S S N I V E R S I CONTENTS U T Y P R 3 Alabama Quilts ✦ Huff / King E 9 The Amazing Jimmi Mayes ✦ Mayes / Speek S ✦ S 9 Big Jim Eastland Annis ✦ O 27 Bohemian New Orleans Weddle F 32 Breaking the Blockade ✦ Ross M ✦ I 5 Can’t Be Faded Stooges Brass Band / DeCoste I S P S P I I S S 2 Can’t Nobody Do Me Like Jesus! ✦ Stone 33 Chaos and Compromise ✦ Pugh 23 Chocolate Surrealism ✦ Njoroge 7 City Son ✦ Dawkins OUR MISSION 12 Cold War II ✦ Prorokova-Konrad University Press of Mississippi (UPM) tells stories 31 The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev, Volume III ✦ Haney / Forrester of scholarly and social importance that impact our 18 Conversations with Dana Gioia ✦ Zheng 19 Conversations with Jay Parini ✦ Lackey state, region, nation, and world. We are commit- 19 Conversations with John Berryman ✦ Hoffman ted to equality, inclusivity, and diversity. Working 18 Conversations with Lorraine Hansberry ✦ Godfrey at the forefront of publishing and cultural trends, 21 Critical Directions in Comics Studies ✦ Giddens we publish books that enhance and extend the 8 Crooked Snake ✦ Boteler 22 Damaged ✦ Rapport reputation of our state and its universities. 10 Dan Duryea ✦ Peros Founded in 1970, the University Press of 7 Emanuel Celler ✦ Dawkins Mississippi turns fifty in 2020, and we are proud 30 Folklore Recycled ✦ de Caro of our accomplishments. -

FROM MOMENTSTO a MOVEMENT Advancing Civil Rights Through Economic Opportunity

FROM MOMENTSTO A MOVEMENT Advancing Civil Rights through Economic Opportunity 2020 IMPACT REPORT “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and TABLE OF CONTENTS the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This was the promise that all men, yes, Black men as well as Moments Moments that Moments Moments Moments Moments that Build a Saved Small that Shaped that Changed in Healthcare of Esperanza white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of Movement Businesses Policy Banking History happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note in so far as her citizens of color are concerned…But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice 3 6 12 14 20 23 is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So, we have come to cash this check, a check that will give us Moments HOPE Exists to Moments in Moments in Moments in Moments on upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.” in Consumer Close the Racial Homeownership Education Partnership Campus Lending Wealth Gap ― Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. August 28, 1963 27 29 32 36 39 43 Moments of 2020 Corporate Transformation Financials Governance 46 50 56 The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C., includes “The Stone of Hope,” a sculpture of Dr. King created by artist Lei Yixin. MOMENTS THAT BUILD A MOVEMENT 2020 was a year of American reckoning. -

Mississippi Blues Trail Taken by David Leonard

New Stage Theatre presents Book, Lyrics, and Music by Charles Bevel, Lita Gaithers, Randal Myler, Ron Taylor and Dan Wheetman Based on an original idea by Ron Taylor Directed by Peppy Biddy Musical Direction by Sheilah Walker Choreographed by Tiffany Jefferson May 26 – June 7, 2015 Sponsored by Stage Manager Scenic Designer Elise McDonald Jimmy “JR” Robertson Projection Designer and Richart Schug Marvin “Sonny” White Technical Director/ Lighting Designer Properties Designer Brent Lefavor Richard Lawrence Costume Designer Lesley Raybon blues_program_workin2.indd 1 5/21/15 1:50 PM Originally produced on Broadway by Eric Krebs, Jonathan Reinis, Lawrence Horowitz, Anita Waxman, Elizabeth Williams, CTM Productions and Anne Squandron, in association with Lincoln Center Electric Factory Concerts, Adam & David Friedson, Richard Martini, Marcia Roberts and Murray Schwartz. The original cast album, released by MCA Records, was produced and mixed by Spencer Proffer. Photographs from the Mississippi Blues Trail taken by David Leonard. Photographs from the book “Juke Joint” taken by Birney Imes. Welty images - Copyright ©Eudora Welty, LLC; Courtesy Eudora Welty Collection – Mississippi Department of Archives and History Tomato Packer’s Recess Chopping the Field Home by Dark Carrying Ice on Sunday Morning Mother In White Dress and Child Girl with Arms Akimbo Circle of Children Madonna with Coca – Cola “It Ain’t Nothin’ But the Blues” is presented by special arrangement with SAMUEL FRENCH, INC. There will be one 10 minute intermission This production of It Ain’t Nothin’ But the Blues is dedicated to Riley “B.B.” King September 16, 1925 – May 14, 2015 The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. -

Selma Photographer Captured History on 'Bloody Sunday' by MATT PEARCE

Selma photographer captured history on 'Bloody Sunday' By MATT PEARCE As the column of black demonstrators in Selma, Ala., marched two by two over the Edmund Pettus Bridge, James "Spider" Martin and his camera were there to record the scene. It was March 7, 1965. Martin didn’t know it yet, but he was documenting one of the most consequential moments in the history of Alabama. Every photo would become a blow against white supremacy in the South. Martin, then a 25-year-old staff photographer for the Birmingham News, scooted ahead of the action. An Alabama state trooper swings his club at future U.S. Rep. John Lewis, pictured on the ground, during "Bloody Sunday" in Selma, Ala., in 1965. (James "Spider" Martin Photographic Archive) Martin later wrote that while trying to wipe the tear gas from his eyes, he used one of his cameras to block a blow from a trooper’s club. “Excuse me,” the trooper then said, Martin recalled. “I thought you’s a [n-word.]” Martin, who was white, was exasperated by what was happening. “Alabama, God damn, why did you let it happen here?” he remembered thinking. Several of Martin’s photos raced across the Associated Press wire and into history, where, half a century later, they have become a crucial record of the civil rights movement. Earlier this year, the photos were part of a collection purchased from Martin’s estate for $250,000 by the University of Texas’ Briscoe Center for American History. Martin died in 2003. The photos were also “referenced extensively” for the recent film “Selma,” which dramatized the events of the march, said director Ava DuVernay, who called Martin’s work “incredible stuff.” “It was the, at the time, most important thing in his life that he’d ever done,” daughter Tracy Martin said of the weeks that her father spent covering the events leading up to and following "Bloody Sunday" in Selma. -

Module 15.Pdf

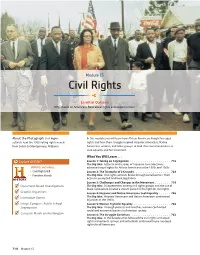

Module 15 Civil Rights Essential Question Why should all Americans have equal rights and opportunities? About the Photograph: Civil Rights In this module you will learn how African Americans fought for equal activists lead the 1965 voting rights march rights and how their struggle inspired Hispanic Americans, Native from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. Americans, women, and other groups to lead their own movements to seek equality and fair treatment. What You Will Learn . Explore ONLINE! Lesson 1: Taking on Segregation . 716 The Big Idea Activism and a series of Supreme Court decisions VIDEOS, including... advanced equal rights for African Americans in the 1950s and 1960s. • Civil Rights Bill Lesson 2: The Triumphs of a Crusade . 728 • Freedom March The Big Idea Civil rights activists broke through racial barriers. Their activism prompted landmark legislation. Lesson 3: Challenges and Changes in the Movement . 738 Document-Based Investigations The Big Idea Disagreements among civil rights groups and the rise of black nationalism created a violent period in the fight for civil rights. Graphic Organizers Lesson 4: Hispanic and Native Americans Seek Equality . 746 Interactive Games The Big Idea Hispanic Americans and Native Americans confronted injustices in the 1960s. Image Compare: Public School Lesson 5: Women Fight for Equality . 756 Segregation The Big Idea Through protests and marches, women confronted social and economic barriers in American society. Carousel: March on Washington Lesson 6: The Struggle Continues . 763 The Big Idea In the decades that followed the civil rights and equal rights movements, groups and individuals continued to pursue equal rights for all Americans. 714 Module 15 DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Timeline of Events 1953–2010 Explore ONLINE! United States Events World Events 1953 1954 Brown v. -

National Museum of African American History and Culture Presents New

Media only: Lindsey Koren (202) 633-4052 or [email protected] Feb. 12, 2015 Abby Benson (202) 633-9495 or [email protected] Media website: http://newsdesk.si.edu National Museum of African American History and Culture Presents New Book Series Based on Photography Collection “The power of photographs is not only the ability to depict events, but to bring human scale to those experiences”—Lonnie G. Bunch III Photography has served a crucial role in providing a visual record of African American history. “Double Exposure,” is a major new multi-volume series based on the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC)’s photography collection. The photography showcases a striking visual account of key historical events, cultural touchstones and private and communal moments to illuminate African American life. In addition to featuring more than 50 photographs from a broad range of African American experiences, each themed volume in the “Double Exposure” series includes contributions by leading contemporary historians, activists, photographers and writers. Many of the images in the series are by famous photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Spider Martin, Wayne F. Miller, Gordon Parks and Ernest C. Withers. There are also iconic images, such as McPherson & Oliver’s “Gordon under Medical Inspection” (circa 1867). These take their place next to unfamiliar or recently discovered images, including work by Rev. Henry Clay Anderson of everyday life in the black community in Greenville, Miss., during the height of the Jim Crow era. “Photography is an art form that connects us all,” said Rhea L. Combs, NMAAHC curator and head of the museum’s Earl W. -

Upstanders Circle of Remembrance Society

UPSTANDERS CIRCLE OF REMEMBRANCE SOCIETY Up-stand-er (n.) “This visit has inspired me to no longer sit back and just watch something happen because it doesn’t involve me. • Stands up for other people and their rights I have realized it is me and my generation’s job to make sure this doesn’t happen again.” • Combats injustice, inequality, or unfairness • Sees something wrong and works to make it right -Macie, 8th grade student visitor Individual Dual Family Friends & Partner Friend Supporter Patron Benefactor Chesed With your support, the Museum can further our mission to teach the history of the Holocaust Family $50 $85 $150 $500 $1,000 $2,500 $5,000 $10,000 and advance human rights to combat prejudice, hatred, and indifference. $300 $25,000 + Discount Rates for Educators / Students $25 $60 $125 [email protected], or 469-399-5205. Lai, Affairs and External information, contact Chief Advancement please at more Kerri Officer, For you. meaningful to the opportunity that most the to are investment areas as a donor, you, allows your allocate to Named after virtue the Hebrew kindness,” this “loving which giving means major society “Chesed,” Discount Rates for Senior Citizens / Military / People with Disabilities / Museum Volunteers / YLI $30 $65 $130 Fair market value of benefits $0 $40 $40 $60 $60 $136 $176 $316 $432 Core Benefits North American Reciprocal Museum access to 1,000+ Museums (narmassociation.org/) ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Number of Adult Member Cards (free admission to permanent and special exhibitions) 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 Plus-One Guest Card (if no name on second Member card, may use to bring a guest) ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Free Admission for Member's Children and Grandchildren (under 18) ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Complimentary Guest Passes (single use) 2 2 4 6 8 10 Parking Discount (Subject to availability. -

Wilson Selectedas Director of Center

Wilson Selected as Director of Center '_". 0_._.. ,' _~ ._~.~ .. "., .m -,.-,---.-~ ....... .,.. .. ."" hades Reagan Wilson, head 91"t~eademic program in Southern Studies since 1990, will succeed Bill Fer- ris as director of the Center. His new .flpOintment will begin July 1, 1998. University Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Gerald Walton echoed the sentiments of Center faculty, staff, and students in a recent comment on Wilson's appointment: "Charles Wil- son is a long-time member of the Uni- versity faculty and is a nationally recognized authority on the South. He will provide outstanding leadership for the Center, and I look forward to work- ing with him." An intellectual and cultural historian, Wilson received a bachelor of arts and a master of arts in history from the Uni- versity of Texas at EI Paso and a doctor- ate of philosophy in history from the University of Texas at Austin. After teaching at the University of Wurzburg, the University of Texas at EI Paso, and Texas Tech University, Wilson came to the Center in 1981 to coedit the 1,634- page Encyclopedia of Southern Culture and to accept a teaching appointment in Southern Studies and History. A native of Tennessee who spent his ty of Texas had already written a disserta- Soon after the publication of the adolescent years in West Texas, Wilson tion on this topic. Encyclopedia in 1989, Wilson became became seriously interested in studying Wilson's subsequent decision to study academic director for the Center. His the South while'working towards his doc- the religion of the South's Lost Cause duties as academic director have toral degree at the University of Texas. -

Civil Rights Historical Investigations

CIVIL RIGHTS HISTORICAL INVESTIGATIONS A FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES PUBLICATION CIVIL RIGHTS HISTORICAL INVESTIGATIONS A FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES PUBLICATION Facing History and Ourselves is an international educational and professional development orga- nization whose mission is to engage students of diverse backgrounds in an examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism in order to promote the development of a more humane and informed citizenry. By studying the historical development of the Holocaust and other examples of genocide, students make the essential connection between history and the moral choices they confront in their own lives. For more information about Facing History and Ourselves, please visit our website at www.facinghistory.org. Copyright © 2010 by Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. Facing History and Ourselves® is a trademark registered in the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office. Facing History and Ourselves Headquarters 16 Hurd Road Brookline, MA 02445-6919 ABOUT FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES Facing History and Ourselves is a nonprofit educational organization whose mission is to engage students of diverse backgrounds in an examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism in order to promote a more humane and informed citizenry. As the name Facing History and Ourselves implies, the organization helps teachers and their students make the essential connections between history and the moral choices they confront in their own lives, and offers a framework and a vocabu- lary -

Spider Martin Captured History by Documenting Civil Rights Battle

8/11/2014 Spider Martin captured history by documenting civil rights battle | www.mystatesman.com Spider Martin captured history by documenting civil rights battle Photojournalist’s work, shown at Briscoe Center, recorded brutality against peaceful protesters Posted: 12:00 a.m. Saturday, Aug. 9, 2014 By Michael Barnes - American-Statesman Staff The power of the central image lies in the void. And what intrudes into that void. To the left are uniformed white officers, guns in holsters, nightsticks in tensed hands, helmets on heads and, for a few, gas masks already strapped into place. They are in motion, moving forward at what appears to be a deliberate pace. + To the right are a half dozen or more African-Americans, jackets hunched over shoulders, hands in pockets or clasped at the waist. They are stationary, staring at the officers. One man holds his right hand to his lips. It is not a threatening gesture. Meanwhile, the lead trooper stretches COPYRIGHT: SPIDER MARTIN out his left arm and points to the black Spider Martin captured many side moments men. Whether he’s telling them to turn during the 1965 Alabama around or simply to halt — they already marches, which included representatives of varied have — is not immediately clear. Yet religious communities. there is no question that this gesture is threatening. Given the asymmetrical possession of weapons, it is clear this will not end well. And it did not. Very soon after that, troopers, some of them mounted, tore into peaceful demonstrators brutally. In that central scene, titled “Two -

Southern Register S/S 2005

the THESouthern NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF SOUTHERN CULTURE •SPRINGRegister/SUMMER 2005 g THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI Faulkner’s Inheritance Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha Conference July 24-28, 2005 n a sense Faulkner’s “inheritance” was the standard turn-of-the-century Southern condition, what Allen Tate years later referred to as the “double focus, a looking two ways.” One of those ways was backward to the antebellum culture and the War between the States Ithat was fought to defend it; the other was toward the present, modern world, with all its implicit and explicit challenges to much of what the Old South had stood for, good and bad. Mrs. L. H. Harris, writing in 1906, put it more poetically. Every Southerner, especially the white males, had to assume two roles simultaneously: to be “himself and his favorite forefather at the same time,” to inhabit “two characters . one which condemns us, more or less downtrodden by facts, to the days of our own years, and one in which we tread a perpetual minuet of past glories.” The Square, by John McCrady (1911-1968), illustrates the 2005 The 32nd annual Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha Conference Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference poster and program will explore for five days some of the complexities of that courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. William Lewis and the Downtown Grill. Flat copies of the poster and two others with McCrady paintings, “double focus,” the way in which Faulkner’s general Southern, Political Rally and Oxford on a Hill, are available for $10.00 each as well as his distinctive “Falkner,” past and present come plus $3.50 postage and handling. -

The Great Society

ARENA’S PAGE STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS The Play Meet the Playwright THE GREAT SOCIETY From the Director’s Notebook WRITTEN BY ROBERT SCHENKKAN | DIRECTED BY KYLE DONNELLY Presidential Profile FICHANDLER STAGE | FEBRUARY 2 — MARCH 11, 2018 Meet the Political Players What is The Great Society? Why are We in Vietnam Three Big Questions Resources THE PLAY It is 1965 and President Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ) is at a critical point in his presidency. He is launching “The Great Society”, an ambitious set of social programs that would increase funds for health care, education and poverty. He also wants to pass the Voting Rights Act, an act that would secure voting rights for minority communities across the country. At each step, Johnson faces resistance. Conservatives like Senator Everett Dirksen are pushing for budget cuts on his social welfare programs. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is losing patience at the lack of progress on voting rights. With rising discrimination against black communities in America, King takes matters into his own hands, organizing a civil rights protest in Selma, Alabama. Outside the U.S., the crisis in Vietnam is escalating. When the Viet Cong attacks a Marine support base, Johnson is faced with a difficult decision: should he deploy more American troops to fight overseas or should he focus on fighting the war on poverty within the U.S.? Time is ticking and the next presidential election is around the corner. In an “There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is only America divided by civil rights protests an American problem — the failure of America to live up to its unique and the anguish of the Vietnam War, can Johnson pave the way for a founding purpose — all men are created equal.” great society? — President Lyndon Baines Johnson, The Great Society Viet Cong — a communist political Additional support is provided by Decker Anstrom and Sherry Hiemstra and the David Bruce Smith Foundation.