Festivals Ric Knowles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Now Until Jun 16. NXNE Music Festival. Yonge and Dundas. Nxne

hello ANNUAL SUMMER GUIDE Jun 14-16. Taste of Little Italy. College St. Jun 21-30. Toronto Jazz Festival. from Bathurst to Shaw. tolittleitaly.com Featuring Diana Ross and Norah Jones. hello torontojazz.com Now until Jun 16. NXNE Music Festival. Jun 14-16. Great Canadian Greek Fest. Yonge and Dundas. nxne.com Food, entertainment and market. Free. Jun 22. Arkells. Budweiser Stage. $45+. Exhibition Place. gcgfest.com budweiserstage.org Now until Jun 23. Luminato Festival. Celebrating art, music, theatre and dance. Jun 15-16. Dragon Boat Race Festival. Jun 22. Cycle for Sight. 125K, 100K, 50K luminatofestival.com Toronto Centre Island. dragonboats.com and 25K bike ride supporting the Foundation Fighting Blindness. ffb.ca Jun 15-Aug 22. Outdoor Picture Show. Now until Jun 23. Pride Month. Parade Jun Thursday nights in parks around the city. Jun 22. Pride and Remembrance Run. 23 at 2pm on Church St. pridetoronto.com topictureshow.com 5K run and 3K walk. priderun.org Now until Jun 23. The Book of Mormon. Jun 16. Father’s Day Heritage Train Ride Jun 22. Argonauts Home Opener vs. The musical. $35+. mirvish.com (Uxbridge). ydhr.ca Hamilton Tiger-Cats. argonauts.ca Now until Jun 27. Toronto Japanese Film Jun 16. Father’s Day Brunch Buffet. Craft Jun 23. Brunch in the Vineyard. Wine Festival (TJFF). $12+. jccc.on.ca Beer Market. craftbeermarket.ca/Toronto and food pairing. Jackson-Triggs Winery. $75. niagarawinefestival.com Now until Aug 21. Fresh Air Fitness Jun 17. The ABBA Show. $79+. sonycentre.ca Jun 25. Hugh Jackman. $105+. (Mississauga). Wednesdays at 7pm. -

923466Magazine1final

www.globalvillagefestival.ca Global Village Festival 2015 Publisher: Silk Road Publishing Founder: Steve Moghadam General Manager: Elly Achack Production Manager: Bahareh Nouri Team: Mike Mahmoudian, Sheri Chahidi, Parviz Achak, Eva Okati, Alexander Fairlie Jennifer Berry, Tony Berry Phone: 416-500-0007 Email: offi[email protected] Web: www.GlobalVillageFestival.ca Front Cover Photo Credit: © Kone | Dreamstime.com - Toronto Skyline At Night Photo Contents 08 Greater Toronto Area 49 Recreation in Toronto 78 Toronto sports 11 History of Toronto 51 Transportation in Toronto 88 List of sports teams in Toronto 16 Municipal government of Toronto 56 Public transportation in Toronto 90 List of museums in Toronto 19 Geography of Toronto 58 Economy of Toronto 92 Hotels in Toronto 22 History of neighbourhoods in Toronto 61 Toronto Purchase 94 List of neighbourhoods in Toronto 26 Demographics of Toronto 62 Public services in Toronto 97 List of Toronto parks 31 Architecture of Toronto 63 Lake Ontario 99 List of shopping malls in Toronto 36 Culture in Toronto 67 York, Upper Canada 42 Tourism in Toronto 71 Sister cities of Toronto 45 Education in Toronto 73 Annual events in Toronto 48 Health in Toronto 74 Media in Toronto 3 www.globalvillagefestival.ca The Hon. Yonah Martin SENATE SÉNAT L’hon Yonah Martin CANADA August 2015 The Senate of Canada Le Sénat du Canada Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4 K1A 0A4 August 8, 2015 Greetings from the Honourable Yonah Martin Greetings from Senator Victor Oh On behalf of the Senate of Canada, sincere greetings to all of the organizers and participants of the I am pleased to extend my warmest greetings to everyone attending the 2015 North York 2015 North York Festival. -

Celebrate Ontario 2020 Successful Applicants Listing

Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Celebrate Ontario 2020 Tourism and Culture Successful Applicants Industries Listing © Destination Ontario ontario.ca/celebrateontario Celebrate Ontario 2020 – Successful Applicants Listing - 1 Event Name Location Funding #BollywoodMonster Mashup Mississauga $35,000 1000 Islands Regatta Brockville $13,727 1000 ISLANDS Waterfront Festival Gananoque $2,500 12th Annual Great Canadian Kayak Challenge & Festival Timmins $9,397 166th Lindsay Exhibition Kawartha Lakes $12,500 2020 Capital Pride Festival Ottawa $32,813 2020 Capital Ukrainian Festival Ottawa $25,000 2020 International Plowing Match & Rural Expo Kawartha Lakes $100,000 2020 Muskoka Summer Season Gravenhurst $9,462 2020 Red Lake Norseman Festival Red Lake $4,400 2020 Stonebridge Wasaga Beach Blues Festival Wasaga Beach $6,350 2020 TAIWANfest Toronto $15,714 2020 TD Markham Jazz Festival Markham $5,500 2021 Kingston Canadian Film Festival Kingston $20,000 21st imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival Toronto $90,863 23rd Annual Community Pow Wow Toronto $2,500 25th Anniversary Ashkenaz Festival Toronto $46,500 46th Annual Ball's Falls Thanksgiving Festival Lincoln $10,000 4th Line Theatre's 2020 Season Cavan Monaghan $57,895 '90s Nostalgia: Electric Circus Edition Vaughan $45,000 Afro Carib Fest (ACF) Toronto $24,512 Animation de la rue Principale Hawkesbury $1,985 Artfest Kingston Kingston $11,448 Celebrate Ontario 2020 – Successful Applicants Listing - 2 Event Name Location Funding ArtsFest Hamilton $15,000 Bay Block Party North Bay $3,536 Because Beer -

Canvas Sky Press History Page 1 of 4

Canvas Sky Press History Page 1 of 4 Press History 2019 (Night Feed) Toronto Fringe Festival Reviews for Night Feed - “NNNNN … Night Feed exquisitely captures a moment in time that feels like an eternity. … This is deeply honest storytelling and the performers keep it profoundly compelling. Although the story will have specific meaning to people who have gone through this experience, it will also appeal universally to anyone who has endured the challenges of life-altering events.” - Debbie Fein-Goldbach, NOW Magazine, July 6 2019, https://nowtoronto.com/stage/theatre/fringe-review-night-feed-2019/ - “Ginette Mohr … and Sarah Joy Bennett … are side-splittingly funny as they bring objects to life in a huge range of demeanours, voices, and accents. …Corinne Murray is exceptional as a mother trying to navigate her inner voice, while simultaneously puppeteering the baby. …As totally unnerving as it is hilariously funny, Night Feed is an ingeniously creative look at a night alone with a new baby.” - Rachel Fagan, Mooney On Theatre, July 5 2019, https://www.mooneyontheatre.com/2019/07/05/night-feed-canvas-sky-theatre-2019-toronto-fringe-revi ew/ - “★★★ … Bennett and Mohr are engaging puppeteers who create a dreamlike, sleep-deprived sensation with their physicality and vocals while giving each puppet a unique personality. Murray’s understated performance keeps the show grounded; with a believable mix of exhaustion, anxiety and patience, she cradles her puppet baby with such care that the emotional payoff of the conclusion hits right at home.” - Carly Maga, July 7 2019, https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/stage/review/2019/07/07/six-shows-you-should-see-at-the-toro nto-fringe-festival.html - “Murray is comically poignant as the Mother; struggling with self-doubt on a few hours of sleep a day, she’s able to brush off some fears and self-criticisms, while others land like a punch to the gut. -

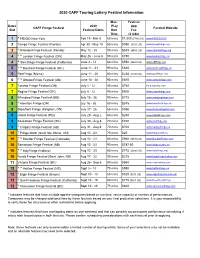

2020 CAFF Touring App Festival Info DB

2020 CAFF Touring Lottery Festival Information Max. Festival Dates 2020 Play App CAFF Fringe Festival Festival Website Slot Festival Dates Run Fee Time ($ Cdn) 1* FRIGID New York Feb 19 - Mar 8 60 mins $1,000 ($785 US) www.FRIGID.NYC 2 Tampa Fringe Festival (Florida) Apr 30 - May 10 60 mins $390 ($300 US) www.tampafringe.org 3 * Orlando Fringe Festival (Florida) May 12 - 25 90 mins $835 ($650 US) www.orlandofringe.org 4 * ^ London Fringe Festival (ON) May 26 - June 6 90 mins $750 www.londonfringe.ca 4 ^ San Diego Fringe Festival (California) June 4 - 14 60 mins $550 ($425 US) www.sdfringe.org 5 * ^ Montreal Fringe Festival (QC) June 11 - 21 90 mins $685 www.montrealfringe.ca 5 PortFringe (Maine) June 11 - 20 60 mins $258 ($200 US) www.portfringe.com 6 * ^ Ottawa Fringe Festival (ON) June 18 - 28 90 mins $685 www.ottawafringe.com 7 Toronto Fringe Festival (ON) July 1 - 12 90 mins $760 fringetoronto.com 7 Regina Fringe Festival (SK) July 8 - 12 90 mins $600 www.reginafringe.com 8 Winnipeg Fringe Festival (MB) July 15 - 26 90 mins $775 www.winnipegfringe.com 8 * Hamilton Fringe (ON) Juy 16 - 26 60 mins $675 www.hamiltonfringe.ca 8 Storefront Fringe (Kingston, ON) July 17 - 26 60 mins $398 www.theatrekingston.com 9 Island Fringe Festival (PEI) July 29 - Aug 2 60 mins $250 www.islandfringe.com 9 Saskatoon Fringe Festival (SK) July 30 - Aug 8 70 mins $760 www.yxefringe.org 9 * Calgary Fringe Festival (AB) July 31 - Aug 8 70 mins $700 www.calgaryfringe.ca 10 * Fringe North (Sault Ste. -

Toronto - Major Events 2011

Toronto - Major Events 2011 Please note: dates are subject to change without notice. Please consult websites. January Next Stage Theatre Festival – Jan. 5 to Jan. 16 ‐‐ www.fringetoronto.com Toronto International Boat Show – Jan. 8 to Jan. 16 ‐‐ www.torontoboatshow.com Interior Design Show – Jan. 27 to Jan. 30 ‐‐ www.interiordesignshow.com Toronto WinterCity Festival – www.toronto.ca/special_events Winterlicious – Jan. 28 to Feb. 10 ‐‐ www.toronto.ca/special_events February Kuumba Festival – Feb. 5 to Feb. 6 ‐‐ www.harbourfrontcentre.com/Kuumba Kuumba Festival – Feb. 12 to Feb. 13 ‐‐ www.harbourfrontcentre.com/Kuumba Auto Show – Feb. 18 to Feb. 27 ‐‐ www.autoshow.ca Masala! Mehndi! Masti! Winterfest – July 23 to July 25 ‐‐ www.masalamehndimasti.com National Home Show – Feb. 18 to Feb. 27 ‐‐ www.nationalhomeshow.com March International Bicycle Show – March 4 to March 6 ‐‐ www.bicycleshowtoronto.com Canadian Music Fest – March 9 to March 13 ‐‐ www.canadianmusicfest.com St. Patrick’s Day Parade – March 13 ‐‐ www.topatrick.com Toronto Sportsmen's Show ‐ March 16 to March 20 ‐‐ www.torontosportshow.ca/ Canada Blooms: The Toronto Flower and Garden Festival – March 15 to March 20 ‐‐ www.canadablooms.com One of a Kind Spring Show & Sale – March 30 to April 3 ‐‐ www.oneofakindshow.com April Sprockets International Film Festival – April 5 to April 17 ‐‐ www.sprockets.ca Creativ Festival – April 15 to April 16 – www.csnf.com Unionville Easter Weekend – April 2 to April 5 – www.unionvilleinfo.com Hot Docs Film Festival – April 28 to May 8 ‐‐ www.hotdocs.ca -

6Th Toronto Entertainment Survey Selected Highlights Report Date: April 6, 2018

6TH TORONTO ENTERTAINMENT SURVEY SELECTED HIGHLIGHTS REPORT DATE: APRIL 6, 2018 CONDUCTED BY FOR MORE INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT ANDREW ARNTFIELD [email protected] TEL 416-408-4446 EXT 226 INTRODUCTION In February 2018, Field Day conducted its 6th Toronto METHODOLOGY Entertainment Survey to gauge the interest in, and attitudes The survey was conducted online. Survey invitations were towards, Toronto’s live entertainment offerings. distributed via email to Field Day’s database of 4,500 The survey looked at nearly 100 GTA attractions in six Southern Ontario residents who have opted in to receive categories: theatre & performing arts organizations; galleries survey and contesting information. The survey link was & museums; festivals, fairs and events; destinations; sports; also promoted via social media (Facebook and Twitter) and concert or arts venues. and on Canadian contesting websites. As an incentive In addition to Toronto attractions, the survey also included to participate in the survey, Field Day offered a chance major Southern Ontario attractions such as African Lion to win a Grand Prize of $1,000 CDN cash, or one of four Safari, the Stratford Festival and Shaw Festival. Second Place Prizes of $250 CDN cash. Respondents were required to complete the survey prior to entering The survey asked respondents to identify which attractions the contest. they attended in the 2017 calendar year, how often they attended each attraction in 2017, and the average size of Field Day gathered over 1,800 responses from adults their group. living in Southern Ontario. Respondents provided basic demographic information including their FSA (the first Respondents were also asked to identify their three three digits of their postal code), age, household income, “All-Time Favourite” attractions. -

2012 Top 100 Winners

2012 Top 100 Winners 11th Annual Holstein Rodeo Weekend (Brampton) 30th Annual Sioux Lookout Blueberry Festival (Sioux Lookout) 49th Annual Rockhound Gemboree (Bancroft) Taste of Asia (Markham) Alight at Night Festival at Upper Canada Village (Morrisburg) All Canadian Jazz Festival (Port Hope) Art in the Park Windsor (Windsor) Aurora Jazz+ Festival (Aurora) Barrie Winterfest and Festival of Ice (Barrie) Blue Mountain Apple Harvest Festival (Blue Mountains) Bon Soo Winter Carnival (Sault Ste. Marie) Brantford International Villages Cultural Festival (Brantford) Buckhorn Fine Art Festival (Buckhorn) Burlington's Canada Day (Burlington) Burlington's Sound of Music Festival (Burlington) CAA Winter Festival of Lights (Niagara Falls) Canada Blooms (Toronto) Canada Day Celebrations (Ottawa) Canada Day Celebrations (Sarnia) Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) (Toronto) Canal Days Marine Heritage Festival (Port Colborne) Carassauga Festival of Cultures (Mississauga) Carrot Fest (Bradford) Carrousel of the Nations (Windsor) Children's Festival (Burlington) Collingwood Elvis Festival (Collingwood) Cruising on King Street (Kitchener) Doors Open Ontario Dundas Cactus Festival (Dundas) Dunnville 38th Mudcat Festival (Dunnville) Festival of Northern Lights (Owen Sound) First Light (Midland) Fort Fright (Kingston) Friendship Festival (Fort Erie) Glengarry Highland Games (Maxville) Hanover Sights & Sounds Festival (Hanover) Hockeyfest (Brantford) Home County Music & Art Festival (London) Huntsville Girlfriends' Getaway Weekend (Huntsville) It's Your Festival -

2019 Endorsement Letters

The City Clerk regularly provides a summary of the letters from the City of Toronto to the Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario (AGCO) in response to requests to endorse temporary liquor licences. The City Clerk processes these requests and issues a letter to the AGCO on behalf of the City of Toronto. Data Date Range: From: 09-Apr-19 To: 31-Dec-19 Generated on January 17, 2020 at 11:02 AM Ward Establishment Event Name and Address Endorsement Requested Starting Ending Dates Starting Ending Time Request for Dates Time Endorsement 02 Phaze 2 Restaurant and Lounge Afrobeat Workshop Temporary Extension of Premises 14-Sep-19 27-Sep-19 05:00 PM 02:00 AM Not 20-21 1500 Royal York Road, Toronto, ON Endorsed 03 Caffe Demetre Taste of The Kingsway Temporary Extension of Premises 06-Sep-19 06-Sep-19 06:00 PM 10:00 PM Endorsed 2962 Bloor St W 03 Caffe Demetre Taste of The Kingsway Temporary Extension of Premises 07-Sep-19 08-Sep-19 11:00 AM 10:00 PM Endorsed 2962 Bloor St W 03 Dakotas Sports Bar and Grill Lake Shore Grilled Cheese Challenge 2019 Temporary Extension of Premises 08-Jun-19 08-Jun-19 11:00 AM 08:00 PM Endorsed 2814 Lake Shore Blvd West Ontario M8V1H7 03 Gabby-s Grill and Tap Taste of The Kingsway Temporary Extension of Premises 06-Sep-19 06-Sep-19 06:00 PM 10:00 PM Endorsed 2899 Bloor St W 03 Gabby-s Grill and Tap Taste of The Kingsway Temporary Extension of Premises 07-Sep-19 08-Sep-19 11:00 AM 10:00 PM Endorsed 2899 Bloor St W 03 Halibut House Fish & Chips Lake Shore Grilled Cheese Challenge 2019 Temporary Extension of Premises -

Show Tickets at Exit

Art by sophia alonzo SHOW TICKETS AT www.theexit.org/fringE EXIT THEATRE, 156 EDDY, sf, ca 415-673-3847 #SFFRinge #EXITTheatre A note from our Founder Welcome and Greetings to the 2019 San Francisco Fringe Festival Community, as we celebrate our 28th Year! Since late May when I took my show, Denial Is A Wonderful Thing, on the road, I have been touring the CAFF Fringe circuit. So far I’ve been to the London, Ontario Fringe Festival, the PortFringe in Portland, Maine and as I write this letter I’m getting ready to head out to the two largest Fringe Festivals in North America: the Winnipeg Fringe and the Edmonton Fringe. 2019 marks the 25th Anniversary of CAFF (The Canadian Association of Fringe Festivals) of which the SF Fringe is a proud member. All CAFF Fringe Festivals are committed to being open access and to returning 100% of the artist ticket price to the performers and companies. It’s a rare tradition in support of artists that’s precious and unique and it allows a wide open door to a wonderful world of, wild, weird, wacky, sometimes bizarre, sometimes world-class, non-curated creativity. The community of artists, audience, staff and volunteers are the core of a Fringe. So welcome and know that you are a vital part of all that happens each year both on stage and off at the San Francisco Fringe Festival. Please see as many shows as you can and remember to Tip the Fringe so we can keep supporting and exploring this amazing world of Fringe together. -

2009 V.1 & Special Events a GUIDE to SUMMER FESTIVALS and EVENTS in TORONTO and the GTA *Free with the Price of Admission

YOUR GUIDE TO THE HOTTEST & COOLEST SUMMER EVENTS FESTIVALS SUMMER 2009 V.1 & Special Events A GUIDE TO SUMMER FESTIVALS AND EVENTS in TORONTO and the GTA *Free with the price of admission. Rides, games and food not included in the price of CNE admission. Visit TheEx.com for details! Summer 2009 V.1 On Line Edition Proud Member of From the editor Publisher and Managing Editor Joey Cee WE HAVE THE HOTTEST Contributors Annette Stallmach, Enzo Iammatteo & COOLEST FESTIVALS Lina Dhingra THIS SUMMER Interns Nilofer Kassam - Editorial Carly Barker - Editorial Sarah Witzel - Editorial Joey Cee, Publisher & Editor Trevor Harris - Graphics Photographers As we continue the celebration of our 15th Anniversary, HOToronto Magazine, in its commitment Aline Sandler, Tom Sandler, Joey Cee, Jody Glaser, Enzo Iammatteo to keeping you informed and enlightened, continues to present you with a host of new on-line download magazine titles. This addition of HOT & COOL FESTIVALS to the roster is the first Website Design DesignSource.com edition. Broadcast Media Division Producer Joey Cee The information compiled in this issue is derived from many sources, solicited and unsolicited. Our HOToronto Magazines team of writers and photographers have been covering festivals for more than a dozen years, and and each year there are more and more festivals popping up all over the city and throughout the GTA. What’s On Where Magazines are published on-line by JCO Communications Inc., Although this information is being transmitted to you via free subscription or as a download, it will 1235 Bay Street, 4th Floor, Toronto, Ontario. M5R 3K4. -

Lessons from Canada's Centennial and Other Celebrations for Planning for Toronto's Participation in Canada 150! a Toronto Strategy for Canada's 150Th in 2017

Attachment Lessons from Canada's Centennial and Other Celebrations for Planning for Toronto's Participation in Canada 150! A Toronto Strategy for Canada's 150th in 2017 August 2014 Past Milestone Celebrations and TO Canada 150! Section 1: Background/Context Council Direction The following report was prepared following City Council direction to begin preparing a regional strategy for the City of Toronto for Canada's 150th anniversary in 2017. On February 19 and 20, 2014 City Council adopted MM48.1 "150th Anniversary of Canadian Confederation": http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2014/mm/bgrd/backgroundfile-66905.pdf 1. City Council direct the General Manager, Economic Development and Culture to engage with citizens and neighbouring municipalities to create a regional strategy for 2017, and host local sessions in libraries, arenas, and community centres to educate citizens about the Centennial and plan for the Sesquicentennial. 2. City Council direct the General Manager, Economic Development and Culture to promote our community to the Provincial and Federal governments with a view to staging a major Sesquicentennial event in Toronto. 3. City Council direct the General Manager, Economic Development and Culture to review our local Centennial history, and look to other past celebrations which may provide inspiration for 2017 planning. 4. City Council direct the General Manager, Economic Development and Culture to create a TO Canada 150! Planning Committee to begin forming partnerships, consulting with residents, residents associations, as well as private sector organizations in planning Toronto-based 2017 initiatives. Why Celebrate? In 2017 Canada will celebrate a milestone, the 150th anniversary of Confederation, beginning with the introduction of the Constitution Act, 1867.