NFS Form 10-900-B OMB No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Mission Is to Be a Favorite Destination

630 ST CLAIR, GROSSE POINTE MI. 313 8846810 FINE WINE & COLD BEER DINEIN · CARRYOUT · CATERING OUR MISSION IS TO BE A FAVORITE DESTINATION FOR ALL OF OUR GUESTS; BREAKFAST, LUNCH OR DINNER WE WANT TO OFFER YOU OLD TIME DINER FAVORITES WITH A NEW AGE FLAIR Life is short, order dessert first. Ask your server for today’s sweet little sheila’s selections Mozzarella Sticks Creamy mozzarella sticks covered in a seasoned Fried Pickles breading, served with ranch 6.99 5 zesty battered pickle spears served with homemade ranch 6.99 Spinach Artichoke Dip Creamy parmesan sauce mixed with diced artichokes and Poutine chopped spinach. Served with tortilla chips 8.99 Layer of crispy fries smothered in brown gravy and sprinkled with mozzarella cheese 7.99 Beer Battered Onion Rings Seasoned beer batter fried golden 5.99 Chili Cheese Fries Guacamole Bed of crinkle fries topped with house made chili Guacamole served with house made tortilla chips 8.99 with loads of cheddar cheese 7.99 { Soups & sides } { Beverages } HOMEMADE DAILY SOUPS Fine Wine or Cold Beer Cup 3.99 Bowl 4.99 QT 12.99 Gal 39.99 Ask your server for selection French Fries 3.79 Side Salad 3.99 Fountain Pop w/meal 2.79 Baked Potato 3.99 Pepsi, Diet Pepsi, Mountain Dew, Diet Dew, Sierra Mist, Mug Root Beer, Cherry Pepsi 2.29 Sweet Potato Fries 5.49 Pita 1.99 w/meal 3.99 Iced Tea or Lemonade 2.29 Coleslaw 2.99 Mashed Potatoes & Gravy 4.99 Flavored Iced Tea or Lemonade 2.59 Applesauce 1.99 Stir Fry Veggies 4.99 Coffee 2.29 Gravy 2.49 Roasted Veggies 4.99 Hot Tea or Cocoa 2.49 Green Beans 2.99 Flavored Hot Tea or Scalloped Apples 4.99 Stuffi ng 2.99 Cocoa Drinks 2.79 Mac n Cheese 4.99 Rice 2.99 Milk Sm. -

Please Click Here 2021 Takeout Menu

2021 Side Orders Children’s Plates 20212021 Lowfat Cottage CheeseSide ..................................Side Orders Orders . 2.95 Children’sChildren’sUnder 12Plates PleasePlates Open Year2021 Round LowfatLowfatCole Cottage SlawCottage ............................................ Cheese Cheese .................................. ..................................Side Orders. .. 2.952.952.25 All Children’s plates are served withUnder UnderapplesauceChildren’s 12 12Please Please and choice Plates of fresh fruit, vegetable or french fries Open Open Year Year Round Round All Children’s plates are served with applesauce Underand choice 12 Please of fresh fruit, vegetable or french fries OpenFrom Year 7 A .RoundM. ColeColeVegetable Slaw Slaw ............................................ ............................................ Lowfat............................................ Cottage Cheese ................................... 2..252.252.25 2.95All Children’s plates are served with applesauce and choice of fresh fruit, vegetable or french fries All Children’s plates are served with applesauce and choice of fresh fruit, vegetable or french fries FromFrom 7 A7 .AM.M. Vegetable ............................................Cole Slaw ............................................. 2.25 2.25 VegetableFrench ............................................ Fries ........................................... 2.25 2.50 Fried Chicken Fingers..................................... 6.95 From 7 A.M. Vegetable ............................................. 2.25 FriedFried -

A HPHC-452 Prog2007 23Ea.Qxd

THE 22ND ANNUAL RHODE ISLAND STATEWIDE Historic Preservation Conference RHODE ISLAND HISTORICAL PRESERVATION & HERITAGE COMMISSION PAWTUCKET, RHODE ISLAND SATURDAY, APRIL 14, 2007 Agenda 8:15 — 9:00 am Registration at Tolman High School Auditorium, 150 Exchange Street 9:00 — 10:45 am Opening Session at Tolman High School Auditorium Welcoming Remarks Keynote Address 1 2007 State Preservation Awards 10:45 — 11:15 am Break 11:15 am — 12:30 pm Session A at session locations 12:30 — 2:00 pm Lunch at the Pawtucket Armory, 172 Exchange Street 2:00 — 3:15 pm Session B at session locations 3:15 — 3:45 pm Break 3:45 — 5:00 pm Session C at session locations 5:00— 6:00 pm Closing Reception at The Grant, 250 Main Street design murphy & murphy Something Old, Something Green rom a perch on top of City Hall, we see historic mill complexes and residential neighborhoods, church steeples and downtown commercial blocks, F and important institutional buildings. Each historic building still in use – or adapted for a new use – embodies energy that would be wasted during demolition and reconstruction, makes use of local materials, and is sited along historic trans- 2 portation routes like the Blackstone River and the Northeast Railroad Corridor. Maintaining and reusing historic resources is fundamentally a green strategy This conference will demonstrate that preserving old buildings, historic downtowns, and traditional land use patterns ensures a level of land, energy, and materials consumption that is sustainable for the future. Learn how revitalizing existing buildings, transportation routes, commercial districts, and brownfields lessens our footprint on open space and greenfields. -

Great Lakes Dining Car

The Great Lakes Dining Car 2009 Year in Review Continuing to tell the story of the lunch wagon and dining car business that prospered in the Great Lakes region. With focus on the Great Lakes and neighboring states, and extra emphasis on Chautauqua County in New York. CONTENTS All correspondence can be sent to: Diner Movements - 3 Michael Engle ¬ Current diners in and out of the Great Lakes Region. 182 Speigletown Rd. Additional coverage on page 5 Troy, NY 12182 Focus on a Manufacturer - 4 [email protected] ¬ More smaller concerns. Hamburger huts Ward & Dickinson - 5 ¬ A look at some Ward & Dickinson news. List of Manufacturers - 2, 6 ¬ The builders of the lunch cars. Discovered on-line - 7 ¬ From EBAY and other on-line “collections” and newspapers. www.NYDiners.com/history.html - 8 ¬ What's on the web-site and what's upcoming. Great Lakes Diner Book - Project - 8 Copyright Hanover Historical Center ¬ Information on the project being contemplated. Dining Car Manufacturers Ward & Dickinson Dining Car Co. - Silver Creek, NY 1925-1938. The most prolific builder of the region. They started in mid 1924 building lunch cars in the open, and became a company in 1925. Their motto was, "They're built to last." Charles Ward left the company in late 1927. They would later start building double diners, which was one diner attached to another diner, length wise. The company built similar looking diners with monitor roofs and green and white swirled stained glass in the upper sashes of their windows. Closson Lunch Wagon Co. - Glens Falls, NY 1902-1912. -

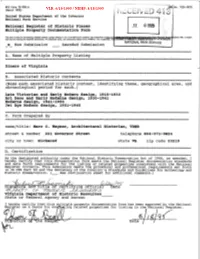

Ti~· F United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUL 61995 Multiple Property Documentation Form

--<._,,. -•r 'c~' c;:"':"~--'~2~ 7 • --~ NPS Form 10-900-b VLR: 6/19/1995 / NRHP: 8/18/1995 ,,., OMB!No. 1024-0018 (March 1992) ti~· f United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUL 61995 Multiple Property Documentation Form This fonn is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to . BIVISlb\\r Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional spaoe, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewnter, w NATIONAL PARK SERVICE x New Submission Amended Submission =============================================================================== A. Name of Multiple Property Listing =============================================================================== Diners of Virginia =============================================================================== B. Associated Historic Contexts =============================================================================== (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Late Victorian and Early Modern design, 1915-1930 Art Deco and Early Moderne design, 1930-1941 Moderne design, 1941-1950 Jet Age Modern design, 1951-1965 ============================================================================== c. Form Prepared by name/title: Marc c. Wagner, Architectural Historian, VDHR street & number 221 Governor street telephone 804-371-0824 city or town Richmond state -

“It's Diner Time!”

Voted #3 Diner #1 Diner in in the Country Georgia “It’s306 CobbDiner Parkway Time!” • Marietta, GA 30060 Phone: (770) 423-9390 • Fax: (770) 499-9814 Visit our other locations: C 4EXAS2OADHOUS !UTHENTI E 3696 Austell Road 3185 Canton Road 2710 Canton Road (770) 434-3535 (770) 218-3474 (770) 427-0490 4751 Sandy Plains Rd 2810 East-West Conn. (470) 767-8771 (470) 299-9700 mariettadiner.com Breakfast ServedServed 2424 HoursHours Eggs and Omelette Platters are served with choice of home fries, French fries, grits or sliced tomatoes and choice of toast (white, wheat or rye) or biscuit JuicesJuices andand FruitsFruits Juice (20-oz.) Orange, grapefruit, tomato, grape, apple, cranberry or V-8 3.65 Whole Banana 1.10 Chilled Fruit Salad Bowl 5.95 | Cup 3.95 Fresh Strawberries Country Fried Bowl 5.95 | Cup 3.95 Steak & Eggs Eggs Served with choice of grits, home fries or sliced Eggs tomatoes. Bread choices are toast, biscuit or pita. Bagel or English muffin .50 extra Two Eggs, any style 5.75 • With Ham, Bacon, or Sausage 9.45 • With Canadian Bacon or Country Ham 9.95 16-oz. Hamburger Steak & Eggs 14.75 HERCULES STEAK & EGGS Grilled Chicken Breast & Eggs 10.99 Jumbo 16-oz. rib eye steak with three eggs 28.59 Grilled Pork Chops & Eggs 15.85 Corned Beef Hash & Eggs 10-OZ. N.Y. STRIP STEAK With two eggs 10.55 & THREE EGGS, ANY STYLE 19.95 Country Fried Steak & Eggs With Country Gravy 12.65 Romanian Steak & Eggs 24.39 Three-EggThree-Egg OmelettesOmelettes Served with choice of grits, home fries or sliced tomatoes. -

GUIDE to the SHAWANGUNK MOUNTAINS SCENIC BYWAY and REGION Shawangunk Mountain Scenic Byway Access Map

GUIDE TO THE SHAWANGUNK MOUNTAINS SCENIC BYWAY AND REGION Shawangunk Mountain Scenic Byway Access Map Shawangunk Mountain Scenic Byway Other State Scenic Byways G-2 How To Get Here Located in the southeast corner of the State, in southern Ulster and northern Orange counties, the Shawangunk Mountains Scenic Byway is within an easy 1-2 hour drive for people from the metro New York area or Albany, and well within a day’s drive for folks from Philadelphia, Boston or New Jersey. Access is provided via Interstate 84, 87 and 17 (future I86) with Thruway exits 16-18 all good points to enter. At I-87 Exit 16, Harriman, take Rt 17 (I 86) to Rt 302 and go north on the Byway. At Exit 17, Newburgh, you can either go Rt 208 north through Walden into Wallkill, or Rt 300 north directly to Rt 208 in Wallkill, and you’re on the Byway. At Exit 18, New Paltz, the Byway goes west on Rt. 299. At Exit 19, Kingston, go west on Rt 28, south on Rt 209, southeast on Rt 213 to (a) right on Lucas Turnpike, Rt 1, if going west or (b) continue east through High Falls. If you’re coming from the Catskills, you can take Rt 28 to Rt 209, then south on Rt 209 as above, or the Thruway to Exit 18. From Interstate 84, you can exit at 6 and take 17K to Rt 208 and north to Wallkill, or at Exit 5 and then up Rt 208. Or follow 17K across to Rt 302. -

Diners Have Spoken: Opentable Reveals the Top 100 Restaurants in Canada and Top Dining Trends for 2019

Diners Have Spoken: OpenTable Reveals The Top 100 Restaurants in Canada and Top Dining Trends for 2019 December 9, 2019 Diner review data reveals Canadians are craving plant based foods and meat substitutions TORONTO, Dec. 9, 2019 /CNW/ -- Celebrating Canada's diverse and rich culinary offerings, OpenTable, the world's leading provider of online restaurant reservations and part of Booking Holdings, Inc., today announced the Top 100 Restaurants in Canada for 2019 according to OpenTable diners. The list is a comprehensive look at the year's most beloved dining spots selected from more than 500,000 verified diner reviews of over 3,000 restaurants across the country. To round up the year, OpenTable is also revealing the top dining trends of 2019, based on diner reviews. From the Italian neighbourhood gem Giulietta in Toronto, the Mediterranean influenced hot spot Escoba Bistro and Wine Bar in Calgary's downtown core, to the equally as delicious as it is visually stunning Osteria Savio Volpe in Vancouver, this year's list showcases OpenTable's eclectic dining options for every occasion across Canada. The restaurants featured have been recognized for their impeccable service, their ability to orchestrate one-of-a-kind dining experiences and for consistently offering unforgettable dishes. Ontario has the greatest number of restaurants included on the list with 55 featured, followed by Alberta with 19, Quebec with 15 and British Columbia with 9 restaurants. Newfoundland and Saskatchewan are also represented on the list. After scouring diner reviews from across the globe for qualitative insights, OpenTable is sharing the top dining trends of the year to complement the Top 100 Restaurants in Canada. -

Skills Unit 4 Reader

GRADE 2 Core Knowledge Language Arts® • New York Edition • Skills Strand The Job Hunt Job The Unit 4 Reader 4 Unit THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF: STATE Book No. PROVINCE Enter information COUNTY in spaces to the left as PARISH instructed. SCHOOL DISTRICT OTHER CONDITION Year ISSUED TO Used ISSUED RETURNED PUPILS to whom this textbook is issued must not write on any page or mark any part of it in any way, consumable textbooks excepted. 1. Teachers should see that the pupil’s name is clearly written in ink in the spaces above in every book issued. 2. The following terms should be used in recording the condition of the book: New; Good; Fair; Poor; Bad. The Job Hunt Unit 4 Reader Skills Strand GRADE 2 Core Knowledge Language Arts® New York Edition Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work to Remix — to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike — If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. -

Breakfast-Menu.Pdf

Allwood Diner Breakfast Specials SERVED MONDAY - FRIDAY 6:00 AM TO 11:00 AM • Specials Not Available For Take-Out • NO. 1 NO. 2 NO. 3 TWO EGGS TWO EGGS PANCAKES with Ham, Bacon, Taylor Ham or Sausage (Pork or Turkey), Served with Home Fries & Toast 5.5 Served with Butter & Syrup 6.5 Served with Home Fries & Toast 7.5 NO. 4 NO. 5 NO. 6 PANCAKES FRENCH TOAST FRENCH TOAST with Ham, Bacon, Taylor Ham or Sausage (Pork or Turkey), with Ham, Bacon, Taylor Ham or Sausage (Pork or Turkey), Served with Butter & Syrup 6.5 Served with Butter & Syrup 8.5 Served with Butter & Syrup 8.5 NO. 7 NO. 8 NO. 9 CLASSIC WAFFLE CLASSIC WAFFLE CHEESE OMELETTE with Ham, Bacon, Taylor Ham or Sausage (Pork or Turkey), with Choice of American, Cheddar or Swiss Cheese, Served with Butter & Syrup 7.5 Served with Butter & Syrup 9.5 served with Home Fries & Toast 8 All Above Served with Small Juice & Hot Coffee or Hot Tea Morning Favorites JIMMY’S BELLY BUSTER 12 GRAND SLAM 12.5 BREAKFAST SAMPLER 12 Short Stack of Pancakes, Two Eggs, Any Style, Choice of Cheese Omelette with Choice of Bacon, Three Eggs, Any Style, with Bacon, Bacon and Sausage (Pork or Turkey), Sausage or Ham, served with Home Fries Ham and Sausage (Pork or Turkey), served with Home Fries & Short Stack of Pancakes served with Home Fries and Toast RIB-EYE STEAK & EGGS 16 New! AVOCADO TOAST 11 CORNED BEEF HASH & EGGS 9 Rib-Eye Steak & Two Eggs, Any Style Smashed Avocados on Toasted Multi-Grain Bread, A Delicious Blend of Shredded Homemade Corned Beef served with Home Fries and Toast topped with EVOO, Lime -

Breakfast Meat Add-Ons Jazz Em’Up Homefries

440 River Street Fitchburg, MA 01420 978-345-8030 Monday, Tuesday, 5:00am – 2:00pm Wednesday,Thursday, Friday 5:00am – 7:00pm Saturday & Sunday 5:00am- 1:00pm *Cash Only* #1 Two Eggs Homefries & Toast #2 Two Eggs Two Cakes or French Toast $3.75 Choice of Ham Bacon or Sausage $6.00 #3 Egg & Cheese on Bulkie Choice of Ham Bacon or Sausage $4.00 #4 Three Cakes or French Toast Homefries #5 Three Eggs Homefries & Toast Choice of Ham Bacon or Sausage Choice of Ham Bacon or Sausage $7.00 $7.00 #6 Everything in #5 including Choice of 2 cakes or 2 French Toast $8.25 FAMILY FAVORITES INCLUDE HOMEFRIES CHELONI’S TWO EGG OMLETT DAVES THREE EGG OMLETT Cheese & One Favorite Ingredient Cheese & Two Favorite Ingredients w/Toast $6.25 w/Toast $8.25 THE THREE EGG SCRAMBLER PIE’S STUFFED FRENCH TOAST Cheese & Two Favorite Ingredients Layered w/cheese & Two Favorite Ingredients w/Toast $8.25 $8.25 BEEFY-MAN STEAK TIPS Three Eggs Homefries & Toast $9.50 BREAKFAST MEAT ADD-ONS JAZZ EM’UP HOMEFRIES Ham or Bacon ……………. $2.75 Hot Off The Grill…. $1.75 Sausage Patty or Links ….. $2.75 Cajun Spice Sprinkle … $2.00 Italian Sausage …………… $3.00 Sautéed Onions … $2.25 Homemade Grey Corned Beef Hash $3.50 Spice & Onions … $2.50 Cheesy Cheddar…. $2.75 PERFECTLEY POACHED EGGS Half $6.50 Full $8.50 Includes Homefries Hot Off The Grill w/Hollandaise or cheddar sauce • EGGS BENEDICT • EGGS FLORENTINE • EGGS CORDSEE • EGGS IRISH • HOMEMADE SAUSAGE GRAVY OVER BISCUITS Half $6.50 Full $8.50 Sweet Treats MICKEY MOUSE PANCAKE $2.50 Or Flavored w/ whip cream 3 FANCY FLAVORED PANCAKES OR FRENCH TOAST w/ homefries $7.00 Get Fruity: Get Chippy: Strawberries Chocolate Chips Blueberries Peanut Butter Chips Banana’s Butterscotch Chips Cinnamon Apples Walnuts BELGUM WAFFLE Half $6.50 Full $8.50 w/choice of strawberries, blueberries or hot apples SIMPLE SIDE ORDERS Toast $1.25 Single Plain Pancake $1.75 English Muffin $1.75 Singled Flavored Pancake $2.25 Plain Bagel $2.00 French Toast (3) $4.25 w/cream cheese $2.25 Pancakes (3) ……. -

Breakfast Menu

Breakfast Menu 160 BERGEN BLVD • FAIRVIEW NJ 07022 • 201-943-6719 BEACONDINERNJ.COM cafe corner Extra Shot of Espresso 2.00 • Add Hazelnut, Caramel, Vanilla or Chocolate .75 HOT COFFEE 2.00 LATTE 4.50 COLD BREW ICED COFFEE 3.00 ICED LATTE 5.00 ESPRESSO 3.50 ICED CARAMEL MACCHIATO ICED ESPRESSO 4.00 Espresso, Caramel & Milk 5.00 FRAPPE ICED COFFEE 4.00 CHAI LATTE 5.00 CAPPUCCINO 4.50 CAFE MOCHA BLACK TEA 2.00 Espresso, Chocolate, Steamed Milk HERBAL TEA 2.50 & Whipped Cream 5.00 HOT CHOCOLATE 4.00 GREEK COFFEE 3.50 spiked coffee Beverages CAFÉ ROMA Espresso, Sambuca, Steamed Milk & Juices & Whipped Cream 6.50 FOUNTAIN SODA 2.75 CAFE ITALIANO ICED TEA 2.75 Espresso, Disarrono, Steamed Milk Raspberry, Green Tea, Sweetened or Unsweetened & Whipped Cream 6.50 PELLEGRINO 3.00 IRISH COFFEE Coffee, Baileys Irish Cream, Jameson FRUIT JUICES & Whipped Cream 7.50 Cranberry, Grapefruit, Apple or Pineapple (8 oz) 2.50 • ( 12 oz) 3.50 DARK KNIGHT Chocolate Ice Cream FRESHLY SQUEEZED ORANGE JUICE blended with Iced Espresso & Kahlua 8.00 (8 oz) 3.50 • ( 12 oz) 5.50 sMootHies Add Protein to Any Smoothie $1.50 PEACH MANGO SMOOTHIE Peach Mango Yogurt & Orange Juice 6.00 VERY BERRY SMOOTHIE Strawberries, Blueberries, Raspberries, Banana, Ice & Yogurt 6.00 STRAWBANANA SMOOTHIE Strawberries, Bananas & Greek Yogurt 6.00 NUTELLA RASPBERRY SMOOTHIE Nutella, Raspberry Syrup & Vanilla Yogurt 6.00 PARADISE SMOOTHIE Mango, Bananas, Vanilla Yogurt & Pineapple Juice 6.00 PEACHES & CREAM SMOOTHIE Peaches, Vanilla Yogurt & Orange Juice 6.00 Breakfast specialties LATINO