Jiraporn Phornprapha* & Weerayuth Podsatiangool, Revisiting The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S19-Seven-Seas.Pdf

19S Macm Seven Seas Nurse Hitomi's Monster Infirmary Vol. 9 by Shake-O The monster nurse will see you now! Welcome to the nurse's office! School Nurse Hitomi is more than happy to help you with any health concerns you might have. Whether you're dealing with growing pains or shrinking spurts, body parts that won't stay attached, or a pesky invisibility problem, Nurse Hitomi can provide a fresh look at the problem with her giant, all-seeing eye. So come on in! The nurse is ready to see you! Author Bio Shake-O is a Japanese artist best known as the creator of Nurse Hitomi's Monster Infirmary Seven Seas On Sale: Jun 18/19 5 x 7.12 • 180 pages 9781642750980 • $15.99 • pb Comics & Graphic Novels / Manga / Fantasy • Ages 16 years and up Series: Nurse Hitomi's Monster Infirmary Notes Promotion • Page 1/ 19S Macm Seven Seas Servamp Vol. 12 by Strike Tanaka T he unique vampire action-drama continues! When a stray black cat named Kuro crosses Mahiru Shirota's path, the high school freshman's life will never be the same again. Kuro is, in fact, no ordinary feline, but a servamp: a servant vampire. While Mahiru's personal philosophy is one of nonintervention, he soon becomes embroiled in an ancient, altogether surreal conflict between vampires and humans. Author Bio Strike Tanaka is best known as the creator of Servamp and has contributed to the Kagerou Daze comic anthology. Seven Seas On Sale: May 28/19 5 x 7.12 • 180 pages 9781626927278 • $15.99 • pb Comics & Graphic Novels / Manga / Fantasy • Ages 13 years and up Series: Servamp Notes Promotion • Page 2/ 19S Macm Seven Seas Satan's Secretary Vol. -

Costellazione Manga: Explaining Astronomy Using Japanese Comics and Animation

Costellazione Manga: explaining astronomy using Japanese comics and animation Downloaded from: https://research.chalmers.se, 2021-09-30 20:30 UTC Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Dall` Olio, D., Ranalli, P. (2018) Costellazione Manga: explaining astronomy using Japanese comics and animation Communicating Astronomy with the Public Journal(24): 7-16 N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. research.chalmers.se offers the possibility of retrieving research publications produced at Chalmers University of Technology. It covers all kind of research output: articles, dissertations, conference papers, reports etc. since 2004. research.chalmers.se is administrated and maintained by Chalmers Library (article starts on next page) Costellazione Manga: Explaining Astronomy Using Japanese Comics and Animation Resources Daria Dall’Olio Piero Ranalli Keywords Onsala Space Observatory, Chalmers Combient AB, Göteborg, Sweden; Public outreach, science communication, University of Technology, Sweden; Lund Observatory, Sweden informal education, planetarium show, ARAR, Planetarium of Ravenna and ASCIG, Italy [email protected] learning development [email protected] Comics and animation are intensely engaging and can be successfully used to communicate science to the public. They appear to stimulate many aspects of the learning process and can help with the development of links between ideas. Given these pedagogical premises, we conducted a project called Costellazione Manga, in which we considered astronomical concepts present in several manga and anime (Japanese comics and animations) and highlighted the physics behind them. These references to astronomy allowed us to introduce interesting topics of modern astrophysics and communicate astronomy-related concepts to a large spectrum of people. -

The Dissemination of Japanese Manga in China

Lund University Center for East and South-East Asian Studies Masters Programme in Asian studies East and Southeast Asian track Spring semester, 2005 The Dissemination of Japanese Manga in China: The interplay of culture and social transformation in post reform period Author: Yang Wang Supervisor: Anna Jerneck Acknowledgements I want to thank my teachers in Lund University, who gave me the opportunity to do research for my thesis. I want to thank teachers in Waseda University for the summer course. I also want to thank my family who has always been supportive. And finally, I want to thank all the friends I have met with in Sweden, Japan and China. 2 Abstract The thesis is a combination of both research fieldwork in sociology and documentary study on the historical development of Japanese animation (and manga) within China in the past two decades. The author tries to reveal some of the social changes taken place in Chinese society through a prevailing foreign culture that once did not even exist. The thesis examines the background, the initiation and developing course of Japanese animation (and manga) while trying to find out how it was distributed and received in the country. By looking into the history of Japanese animation (and manga) in China, several points can be made to the subject. 1) The timing of Japanese animation (and manga) entering China is to the moment of political and social significance. The distribution and consuming of a once considered children program has reflected almost every corner of the social transformation. 2) It has educated the young generation with a blurred idea of modernity at the first place while partly changed their worldview that driving them further away from the lost tradition. -

Hallo Fellow Members of Bellatrix! Welcome to the First 2016 Edition of the Chimera

Hallo fellow members of Bellatrix! Welcome to the first 2016 edition of the Chimera. This is your new Mother of Monsters writing. My legal name is Charisse James, which you will need to use if you ever wish to email me. I answer to Sky and use the “she/her/them/they” pronouns. As the Mother of Monsters, it is my duty to oversee the editing and publishing of each edition of the Chimera. For 2016, the Chimera will be a monthly edition, printed in the last week of every month. The Chimera is a collection of artwork, story serials, fan fictions, book reviews, poems, jokes, blog posts, and anything really that revolves around Manga, Anime, Fantasy, Science Fiction, Manhwa, and Comics. The Chimera depends on student contribution. If you are a current MHC student, a member of Bellatrix and/or Renegades, feel free to email me at [email protected], with your submissions. Here are the guidelines: 1) It must be your own work plagiarism is not tolerated. If you wish to submit something and claim that it is yours, it is best that that be so. If you are submitting work on behalf of someone else, make sure that you have their permission. 2) All work will be reviewed and must be approved by an editor before submissions. 3) Only current Mount Holyoke Students may submit to the Chimera. That is, classes of 2019, 2018, 2017, and 2016. All other students can send their submissions in to the Bellorophan on Tumblr. 4) It is preferable that all written work be five pages or less. -

Seven Seas Will Release Re:Monster As Single PRICE: $12.99 / $15.99 CAN

S E V E N S E A S Kanekiru Kogitsune Re:Monster Vol. 4 A young man begins life anew as a lowly goblin in this action-packed shonen fantasy manga! Tomokui Kanata has suffered an early death, but his adventures are far from over. He is reborn into a fantastical world of monsters and magic--but as a lowly goblin! Not about to let that stop him, the now renamed Rou uses his new physical prowess and his old memories to plow ahead in a world where consuming other creatures allows him to acquire their powers. KEY SELLING POINTS: * POPULAR MANGA SUBJECT: Powerful shonen-style artwork and ON-SALE DATE: 8/27/2019 fast-paced action scenes will appeal to fans of such fantasy series as Overlord ISBN-13: 9781626927100 and Sword Art Online. * SPECIAL FEATURES: Seven Seas will release Re:Monster as single PRICE: $12.99 / $15.99 CAN. volumes with at least two full-color illustrations in each book. PAGES: 180 * BASED ON LIGHT NOVEL: The official manga adaptation of the popular SPINE: 181MM H | 5IN W IN Re:Monster light novel. CTN COUNT: 42 * SERIES INFORMATION: Total number of volumes are currently unknown SETTING: FANTASY WORLD but will have a planned pub whenever new volumes are available in Japan. AUTHOR HOME: KANEKIRU KOGITSUNE - JAPAN; KOBAYAKAWA HARUYOSHI - JAPAN 2 S E V E N S E A S Strike Tanaka Servamp Vol. 12 The unique vampire action-drama continues! When a stray black cat named Kuro crosses Mahiru Shirota's path, the high school freshman's life will never be the same again. -

Costellazione Manga: Explaining Astronomy Using

Costellazione Manga: Explaining Astronomy Using Japanese Comics and Animation Resources Daria Dall’Olio Piero Ranalli Keywords Onsala Space Observatory, Chalmers Combient AB, Göteborg, Sweden; Public outreach, science communication, University of Technology, Sweden; Lund Observatory, Sweden informal education, planetarium show, ARAR, Planetarium of Ravenna and ASCIG, Italy [email protected] learning development [email protected] Comics and animation are intensely engaging and can be successfully used to communicate science to the public. They appear to stimulate many aspects of the learning process and can help with the development of links between ideas. Given these pedagogical premises, we conducted a project called Costellazione Manga, in which we considered astronomical concepts present in several manga and anime (Japanese comics and animations) and highlighted the physics behind them. These references to astronomy allowed us to introduce interesting topics of modern astrophysics and communicate astronomy-related concepts to a large spectrum of people. In this paper, we describe the methodology and techniques that we developed and discuss the results of our project. Depending on the comic or anime considered, we can introduce general topics such as the difference between stars, planets and galaxies or ideas such as the possibility of finding life on other planets, the latest discoveries of Earth-like planets orbiting other stars or the detection of complex organic molecules in the interstellar space. When presenting the night sky and the shapes of constellations, we can also describe how the same stars are perceived and grouped by different cultures. The project outcomes indicate that Costellazione Manga is a powerful tool to popularise astronomy and stimulate important aspects of learning development, such as curiosity and crit- ical thinking. -

ANIME FAN FEST PANELS SCHEDULE May 6-8, 2016

ANIME FAN FEST PANELS SCHEDULE May 6-8, 2016 MAY 6, FRIDAY CENTRAL CITY game given a bit of Japanese polish; players wager their Kingdom Hearts is one of the best-selling, and most 4:00pm - 5:00pm yen on their knowledge of a variety of tricky clues in their complex video game series of all time. In anticipation OTAKU USA’S ANIME WORTH WATCHING Now is probably quest to become Jeopardy! champion! of KHIII, we will be going over all aspects of the series the best time in history to be an anime fan. With tons 5:30pm- 6:30pm in great detail such as: elements of the plot, music, lore, of anime freely (and legally) available, the choices are BBANDAI NAMCO ENTERTAINMENT PRESENTS: ANIME and more. As well as discussing theories and specu- endless...which makes it all the more difficult for anime GAMES IN AMERICA Join Bandai Namco for a behind- lations about what is to come in the future. A highly fans to find out WHICH they should watch. Otaku USA the-scenes look at what it’s like working for the premier educational panel led by your host, Kyattan, this panel Magazine’s Daryl Surat (www.animeworldorder.com) Anime videogame publisher, the process and challenges is friendly to those who haven’t played every game, and NEVER accepts mediocrity as excellence and has prepared of bringing over anime-based and Japanese game content those who are confused about its plot. a selection of recommendations, as covered in the publi- to the Western market, and exclusive insider-only looks at 6:00pm- 7:00pm cation’s 9+ year history! Bandai Namco’s upcoming titles. -

Homosexualité Et Manga : Le Yaoi

Homosexualité et manga : le yaoi Articles, entretiens, chroniques et manga Éditions H Éditorial « Si tu ne trouves pas ce que tu cherches, fais-le ! » : c’est ce conseil, que je donnais déjà il y a quelques années sur le forum d’un site spécialisé dans les mangas, qui a été appliqué avec la collection Manga 10 000 images. Déplorer le manque d’articles de fond sur le manga est une chose mais ne rien faire pour que cela change ne permet pas de tenir longtemps une telle position. Manga 10 000 images est donc une collection d’ouvrages à thème, en quelque sorte une revue d’étude sur la bande dessinée japonaise. À propos, pourquoi ce titre ? Il nous a semblé approprié de montrer dès le début que la diversité serait une de nos préoccupations principales, davantage que la notion de loisir. En jouant sur l’idéogramme « man » (10 000), nous reprenons l’idée du créateur du terme, Shôtarô Ishinomori, qui voulait montrer que la bande dessinée japonaise ne se limitait pas au story manga à la Tezuka, c’est-à-dire aux œuvres de divertissement à destination des enfants. C’est dans le même état d’esprit que Manga 10 000 images va s’efforcer au fi l des publications de montrer que le manga est bien plus diversifi é que ce que l’on pourrait penser au premier abord. Quatre numéros sont déjà planifi és, à raison d’un tous les six mois, chacun sur un thème différent, avec des rédacteurs différents, spécialisés dans le domaine abordé afi n de proposer des articles adaptés, notamment au lectorat concerné. -

I. Early Days Through 1960S A. Tezuka I. Series 1. Sunday A

I. Early days through 1960s a. Tezuka i. Series 1. Sunday a. Dr. Thrill (1959) b. Zero Man (1959) c. Captain Ken (1960-61) d. Shiroi Pilot (1961-62) e. Brave Dan (1962) f. Akuma no Oto (1963) g. The Amazing 3 (1965-66) h. The Vampires (1966-67) i. Dororo (1967-68) 2. Magazine a. W3 / The Amazing 3 (1965) i. Only six chapters ii. Assistants 1. Shotaro Ishinomori a. Sunday i. Tonkatsu-chan (1959) ii. Dynamic 3 (1959) iii. Kakedaze Dash (1960) iv. Sabu to Ichi Torimono Hikae (1966-68 / 68-72) v. Blue Zone (1968) vi. Yami no Kaze (1969) b. Magazine i. Cyborg 009 (1966, Shotaro Ishinomori) 1. 2nd series 2. Fujiko Fujio a. Penname of duo i. Hiroshi Fujimoto (Fujiko F. Fujio) ii. Moto Abiko (Fujiko Fujio A) b. Series i. Fujiko F. Fujio 1. Paaman (1967) 2. 21-emon (1968-69) 3. Ume-boshi no Denka (1969) ii. Fujiko Fujio A 1. Ninja Hattori-kun (1964-68) iii. Duo 1. Obake no Q-taro (1964-66) 3. Fujio Akatsuka a. Osomatsu-kun (1962-69) [Sunday] b. Mou Retsu Atarou (1967-70) [Sunday] c. Tensai Bakabon (1969-70) [Magazine] d. Akatsuka Gag Shotaiseki (1969-70) [Jump] b. Magazine i. Tetsuya Chiba 1. Chikai no Makyu (1961-62, Kazuya Fukumoto [story] / Chiba [art]) 2. Ashita no Joe (1968-72, Ikki Kajiwara [story] / Chiba [art]) ii. Former rental magazine artists 1. Sanpei Shirato, best known for Legend of Kamui 2. Takao Saito, best known for Golgo 13 3. Shigeru Mizuki a. GeGeGe no Kitaro (1959) c. Other notable mangaka i. -

Protoculture Addicts Is ©1987-2004 by Protoculture

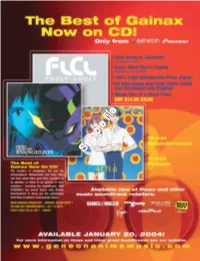

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ P r o t o c u l t u r e A d d i c t s # 8 0 January / February 2004. Published bimonthly by Protoculture, P.O. Box 1433, Station B, Montreal, Qc, ANIME VOICES Canada, H3B 3L2. Web: http://www.protoculture-mag.com Presentation ............................................................................................................................ 4 Letters ................................................................................................................................... 70 E d i t o r i a l S t a f f Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] – Publisher / Editor-in-chief [email protected] NEWS Miyako Matsuda [MM] – Editor / Translator ANIME & MANGA NEWS: Japan ................................................................................................. 5 Martin Ouellette [MO] – Editor ANIME RELEASES (VHS / R1 DVD) .............................................................................................. 6 PRODUCTS RELEASES (Live-Action, Soundtracks) ......................................................................... 7 C o n t r i b u t i n g E d i t o r s MANGA RELEASES .................................................................................................................... 8 Asaka Dawe, Keith Dawe, Kevin Lillard, James S. Taylor MANGA SELECTION .................................................................................................................. 8 P r o d u c t i o n A s s i s t a n t s ANIME & MANGA NEWS: North -

Mangas Jeunesse

Titre construit 1er responsable Série Genre A silent voice (1) : A silent voice Ōima, Yoshitoki (1989 - ...) A silent voice / Yoshitoki Ōima [Ki-oon] Fiction A silent voice (2) : A silent voice Ōima, Yoshitoki (1989 - ...) A silent voice / Yoshitoki Ōima [Ki-oon] Fiction A silent voice (3) : A silent voice Ōima, Yoshitoki (1989 - ...) A silent voice / Yoshitoki Ōima [Ki-oon] Fiction A silent voice (4) : A silent voice Ōima, Yoshitoki (1989 - ...) A silent voice / Yoshitoki Ōima [Ki-oon] Fiction A silent voice (5) : A silent voice Ōima, Yoshitoki (1989 - ...) A silent voice / Yoshitoki Ōima [Ki-oon] Fiction A silent voice (6) : A silent voice Ōima, Yoshitoki (1989 - ...) A silent voice / Yoshitoki Ōima [Ki-oon] Fiction A silent voice (7) : A silent voice Ōima, Yoshitoki (1989 - ...) A silent voice / Yoshitoki Ōima [Ki-oon] Fiction Alchimia (1) : Alchimia Bailly, Samantha (1988 - ...) Alchimia / Eric Sanvoisin [Editions Nathan] Fiction Alchimia (2) : Alchimia Bailly, Samantha (1988 - ...) Alchimia / Eric Sanvoisin [Editions Nathan] Fiction Alchimia (3) : Alchimia Bailly, Samantha (1988 - ...) Alchimia / Eric Sanvoisin [Editions Nathan] Fiction Alice au royaume de coeur (1) : Alice au royaume de coeur QuinRose Alice au royaume de coeur / QuinRose [Ki-oon] Alice au royaume de coeur (2) : Alice au royaume de coeur QuinRose Alice au royaume de coeur / QuinRose [Ki-oon] Alice au royaume de coeur (3) : Alice au royaume de coeur QuinRose Alice au royaume de coeur / QuinRose [Ki-oon] Alice au royaume de coeur (4) : Alice au royaume de coeur QuinRose -

Proyecto Integral Para Revista De Anime Y Manga

UNIVERSIDAD INSURGENTES PLANTEL XOLA LICENCIATURA EN DISEÑO Y COMUNICACIÓN VISUAL CON INCORPORACION A LA U.N.A.M. CLAVE 3315-31 “PROYECCIÓN INTEGRAL PARA REVISTA DE ANIME Y MANGA” “PROUESTA EN CONTENIDO Y FORMACIÓN QUE INTERESE A LA JUVENTUD MEXICANA” T E S I S QUE PARA OBTENER EL TITULO DE: LICENCIADO EN DISEÑO Y COMUNICACIÓN VISUAL P R E S E N T A OMAR GARCÍA OCAMPO ASESORA: LIC. CLAUDIA BEATRIZ VÁZQUEZ BARAJAS MEXICO D.F. 2008 Neevia docConverter 5.1 PROYECCIÓN INTEGRAL PARA REVISTA DE ANIME Y MANGA “La imaginación es una de las partes más importantes de la vida, sin ella no somos nada, pero con ella dominamos al mundo...” Neevia2 docConverter 5.1 Índice Pag. Capítulo I El diseño editorial en la revista. 1.1 El Diseño y la Comunicación Visual .......................................................................................8 1.2 Areas del Diseño y la Comunicación Visual .........................................................................10 1.3 Diseño Editorial .........................................................................................................................11 1.4 Historia de la revista..................................................................................................................16 1.5 La revista en México ................................................................................................................18 1.6 Concepto y función de la revista ..........................................................................................19 1.7 Elementos de diseño en la revista