World Wide Web Interface Study: Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Web Site Metadata

Web Site Metadata Erik Wilde and Anuradha Roy School of Information UC Berkeley Abstract. Understanding the availability of site metadata on the Web is a foundation for any system or application that wants to work with the pages published by Web sites, and also wants to understand a Web site’s structure. There is little information available about how much information Web sites make available about themselves, and this paper presents data addressing this question. Based on this analysis of available Web site metadata, it is easier for Web-oriented applications to be based on statistical analysis rather than assumptions when relying on Web site metadata. Our study of robots.txt files and sitemaps can be used as a starting point for Web-oriented applications wishing to work with Web site metadata. 1 Introduction This paper presents first results from a project which ultimately aims at pro- viding accessible Web site navigation for Web sites [1]. One of the important intermediary steps is to understand how much metadata about Web sites is made available on the Web today, and how much navigational information can be extracted from that metadata. Our long-term goal is to establish a standard way for Web sites to expose their navigational structure, but since this is a long-term goal with a long adoption process, our mid-term goal is establish a third-party service that provides navigational metadata about a site as a service to users interested in that information. A typical scenario would be blind users; they typically have difficulties to navigate Web sites, because most usability and accessibility methods focus on Web pages rather than Web sites. -

Using Information Architecture to Evaluate Digital Libraries, the Reference Librarian, 51, 124-134

FAU Institutional Repository http://purl.fcla.edu/fau/fauir This paper was submitted by the faculty of FAU Libraries. Notice: ©2010 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. This is an electronic version of an article which is published and may be cited as: Parandjuk, J. C. (2010). Using Information Architecture to Evaluate Digital Libraries, The Reference Librarian, 51, 124-134. doi:10.1080/027638709 The Reference Librarian is available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02763870903579737 The Reference Librarian, 51:124–134, 2010 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0276-3877 print/1541-1117 online DOI: 10.1080/02763870903579737 WREF0276-38771541-1117The Reference Librarian,Librarian Vol. 51, No. 2, Feb 2009: pp. 0–0 Using Information Architecture to Evaluate Digital Libraries UsingJ. C. Parandjuk Information Architecture to Evaluate Digital Libraries JOANNE C. PARANDJUK Florida Atlantic University Libraries, Boca Raton, FL Information users face increasing amounts of digital content, some of which is held in digital library collections. Academic librarians have the dual challenge of organizing online library content and instructing users in how to find, evaluate, and use digital information. Information architecture supports evolving library services by bringing best practice principles to digital collection development. Information architects organize content with a user-centered, customer oriented approach that benefits library users in resource discovery. The Publication of Archival, Library & Museum Materials (PALMM), -

SEO Fundamentals: Key Tips & Best Practices For

SEO Fundamentals 1 SEO Fundamentals: Key Tips & Best Practices for Search Engine Optimization The process of Search Engine Optimization (SEO) has gained popularity in recent years as a If your organization’s means to reach target audiences through improved web site positioning in search engines. mission has to do with However, few have an understanding of the SEO methods employed in order to produce such environmental results. The following tips are some basic best practices to consider in optimizing your site for protection, are your improved search engine performance. target visitors most likely to search for Identifying Target Search Terms “acid rain”, “save the forests”, “toxic waste”, The first step to any SEO campaign is to identify the search terms (also referred to as key “greenhouse effect”, or terms, or key words) for which you want your site pages to be found in search engines – these are the words that a prospective visitor might type into a search engine to find relevant web all of the above? Do sites. For example, if your organization’s mission has to do with environmental protection, are you want to reach your target visitors most likely to search for “acid rain”, “save the forests”, “toxic waste”, visitors who are local, “greenhouse effect”, or all of the above? Do you want to reach visitors who are local, regional regional or national in or national in scope? These are considerations that need careful attention as you begin the scope? These are SEO process. After all, it’s no use having a good search engine ranking for terms no one’s considerations that looking for. -

Digital Library Federation

SPRING FORUM 2005 WESTIN HORTON PLAZA SAN DIEGO, CA APRIL 13–15, 2005 Washington, D.C. 2 DLF Spring 2005 Forum Printed by Balmar, Inc. Copyright © 2005 by the Digital Library Federation Some rights reserved. The Digital Library Federation Council on Library and Information Resources 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20036 http://www.diglib.org It has been ten years since the founders of the Digital Library Federation signed a charter formalizing their commitment to leverage their collective strengths against the challenges faced by one and all libraries in the digital age. The forums—began in summer 1999—are an expression of this commitment to work collaboratively and congenially for the betterment of the entire membership. DLF Spring 2005 Forum 3 CONTENTS Acknowledgments……………………………………………..4 Site Map………………………………………………………..5 Schedule………………………………………………………..7 Program and Abstracts………………………………………..11 Biographies……………………………………………...........33 Appendix A: What is the DLF?................................................50 Appendix B: Recent Publications…………………………….53 Appendix C: DLF-Announce Listserv…..................................56 4 DLF Spring 2005 Forum ACKNOWLEDGMENTS DLF Forum Fellowships for Librarians New To the Profession The Digital Library Federation would like to extend its congratulations to the following for winning DLF Forum Fellowships: • John Chapman, Metadata Librarian, University of Minnesota • Keith Jenkins, Metadata Librarian, Cornell University • Tito Sierra, Digital Technologies Development Librarian, North Carolina State University • Katherine Skinner, Scholarly Communications Analyst, Emory University • Yuan Yuan Zeng, Librarian for East Asian Studies, Johns Hopkins University DLF Fellowship Selection and Program Committees The DLF would also like to extend our heartfelt thanks to the DLF Spring Forum 2005 Program Committee and Fellowship Selection Committee for all their hard work. -

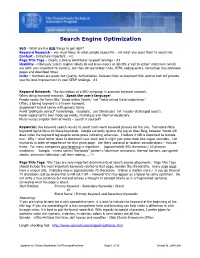

SEO - What Are the BIG Things to Get Right? Keyword Research – You Must Focus on What People Search for - Not What You Want Them to Search For

Search Engine Optimization SEO - What are the BIG things to get right? Keyword Research – you must focus on what people search for - not what you want them to search for. Content – Extremely important - #2. Page Title Tags – Clearly a strong contributor to good rankings - #3 Usability – Obviously search engine robots do not know colors or identify a ‘call to action’ statement (which are both very important to visitors), but they do see broken links, HTML coding errors, contextual links between pages and download times. Links – Numbers are good; but Quality, Authoritative, Relevant links on Keyword-Rich anchor text will provide you the best improvement in your SERP rankings. #1 Keyword Research: The foundation of a SEO campaign is accurate keyword research. When doing keyword research: Speak the user's language! People search for terms like "cheap airline tickets," not "value-priced travel experience." Often, a boring keyword is a known keyword. Supplement brand names with generic terms. Avoid "politically correct" terminology. (example: use ‘blind users’ not ‘visually challenged users’). Favor legacy terms over made-up words, marketese and internal vocabulary. Plural verses singular form of words – search it yourself! Keywords: Use keyword search results to select multi-word keyword phrases for the site. Formulate Meta Keyword tag to focus on these keywords. Google currently ignores the tag as does Bing, however Yahoo still does index the keyword tag despite some press indicating otherwise. I believe it still is important to include one. Why – what better place to document your work and it might just come back into vogue someday. List keywords in order of importance for that given page. -

Automating Navigation Sequences in AJAX Websites

Automating Navigation Sequences in AJAX Websites Paula Montoto, Alberto Pan, Juan Raposo, Fernando Bellas, and Javier López Department of Information and Communication Technologies, University of A Coruña Facultad de Informática, Campus de Elviña s/n 15071 A Coruña, Spain {pmontoto,apan,jrs,fbellas,jmato}@udc.es Abstract. Web automation applications are widely used for different purposes such as B2B integration, automated testing of web applications or technology and business watch. One crucial part in web automation applications is to allow easily generating and reproducing navigation sequences. Previous proposals in the literature assumed a navigation model today turned obsolete by the new breed of AJAX-based websites. Although some open-source and commercial tools have also addressed the problem, they show significant limitations either in usability or their ability to deal with complex websites. In this paper, we propose a set of new techniques to deal with this problem. Our main contributions are a new method for recording navigation sequences supporting a wider range of events, and a novel method to detect when the effects caused by a user action have finished. We have evaluated our approach with more than 100 web applications, obtaining very good results. Keywords: Web automation, web integration, web wrappers. 1 Introduction Web automation applications are widely used for different purposes such as B2B integration, web mashups, automated testing of web applications or business watch. One crucial part in web automation applications is to allow easily generating and reproducing navigation sequences. We can distinguish two stages in this process: − Generation phase. In this stage, the user specifies the navigation sequence to reproduce. -

Web Usability Glossary

USABILITY GLOSSARY TERM DEFINITION above the fold / : The fold' marks the end of the visible part of the web page. Therefore, 'above the below the fold fold' means the area of the web page that is visible without scrolling. 'below the fold' is the area of the web page that requires scrolling to see. accessibility : Accessibility is a prerequisite to usability. If a person can not access a web page he certainly can not use it. Accessibility refers to web page information/content being obtainable and functional to the largest possible audience. It is about providing access to information for those who would otherwise lose their opportunity to use the web. In contrast inaccessible means unobtainable, nonfunctional. accessibility aids : Assistive technology; tools to help people with disabilities to use computers more effectively. affordance / : A situation where an object's sensory characteristics intuitively imply its perceived affordance functionality and use: a button, by being slightly raised above an otherwise flat surface, suggests the idea of pushing it. A lever, by being an appropriate size for grasping, suggests pulling it. A blinking red light and buzzer suggests a problem and demands attention. A chair, by its size, its curvature, its balance, and its position, suggests sitting on it. An affordance is a desirable property of a user interface - software which naturally leads people to take the correct steps to accomplish their goals. banner blindness : This is the situation where a website user ignores banner-like information on a website. The banner information may or may not be an ad. breadcrumbs : Type of web navigation where current location within the website is indicated by a list of pages above the current page in the hierarchy, up to the main page. -

An Algorithm for Gaze Region Estimation on Web Pages

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 6, ISSUE 08, AUGUST 2017 ISSN 2277-8616 An Algorithm For Gaze Region Estimation On Web Pages John K. Njue, Simon G. Maina, Ronald Waweru Mwangi, Michael Kimwele Abstract: Accurate gaze region estimation on the web is important for the purpose of placing marketing advertisements in web pages and monitoring authenticity of user’s response in web forms. To identify gaze region on the web, we need cheap, less technical and non-laboratory setup that minimize user interruptions. This study uses the mouse and keyboard as input devices to collect web usage data. The data collected is categorized into mouse activities, keyboard activities and scroll activities. A regression model is then used to estimate gaze region from the categorized data. The results indicate that although mouse cursor data is generated throughout the user session, the use of data from keyboard presses and scroll from both keyboard and mouse improves the accuracy of identified gaze regions in web usage data. Index Terms: Gaze tracking, gaze region, linear regression model, mouse activities, keyboard activities, scroll activities, web page. ———————————————————— 1 INTRODUCTION 2 LITERATURE REVIEW Eye gaze tracking records eye movements whilst a participant A significant feature of web applications is possibility for non- examines a visual stimulus [1]. Tracking user’s eye gaze and sequential navigation to access items on web documents. eye movements are some of the main ways of studying There is no definite order of determining the sequence in attention on web pages as they provide rich details on user which the text is read in web documents [4]. -

Foraging Goes Mobile: Foraging While Debugging on Mobile Devices

2017 IEEE Symposium on Visual Languages and Human-Centric Computing (VL/HCC) Foraging Goes Mobile: Foraging While Debugging on Mobile Devices David Piorkowski1, Sean Penney2, Austin Z. Henley3, Marco Pistoia1, Margaret Burnett2, Omer Tripp4* , Pietro Ferrara5* 1IBM Research 2Oregon State University 3University of Memphis 4Google 5Julia SRL Yorktown Heights, NY, USA Corvallis, OR, USA Memphis, TN, USA New York, NY, USA Verona, Italy [email protected] {penneys, burnett} [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] @eecs.oregonstate.edu Abstract—Although Information Foraging Theory (IFT) re- Perhaps programmers of larger mobile applications could search for desktop environments has provided important in- also reap such benefits, if their foraging was supported on sights into numerous information foraging tasks, we have been mobile devices. Thus, in order to investigate where foraging unable to locate IFT research for mobile environments. Despite a complex information space on a mobile platform is the same the limits of mobile platforms, mobile apps are increasingly and where it differs from desktop foraging, we conducted a serving functions that were once exclusively the territory of dual replication study. Mobile and desktop platforms are dif- desktops—and as the complexity of mobile apps increases, so ferent, so our study is the type known as a conceptual repli- does the need for foraging. In this paper we investigate, through cation, which “test<s> the same fundamental idea or hypoth- a theory-based, dual replication study, whether and how forag- esis behind the original study, but the operationalizations of ing results from a desktop IDE generalize to a functionally sim- the phenomenon, … may all differ” [9] (italics added). -

The Explorer Bar: Unifying and Improving Web Navigation

The Explorer bar: Unifying and improving web navigation Scott Berkun Program Manager One Microsoft Way Redmond, WA 98052 [email protected] ABSTRACT The Explorer bar is a component of the Internet Explorer web browser that provides a unified model for web navigation activities. The user tasks of searching for new sites, visiting favorite sites, and accessing previously viewed sites are simplified and enhanced by using a single user interface element. Keywords Navigation, bookmark, design, hypertext, searching, browsing more digestible groups that users would understand. We settled on three groupings: web pages the user had not seen INTRODUCTION before, web pages the user was interested in, and web pages the user had visited before. We gave these groupings the names Search, Favorites and History for easier reference. The World Wide Web provides access to an enormous As we sketched out different ideas for solutions to the most amount of information and resources. The primary usability common navigation problems, we recognized that there issues with using the web involve insufficient support for were strong similarities for how users might interact with helping users find and return to individual web pages. The these sets of information. Explorer bar was designed to improve these usability For example, when searching the web using a problems by providing a single well designed user interface search engine, users received a long list of search results. In model for the most common set of web navigation tasks. formal and informal usability studies, we observed many users click on a result link which took them to a new site, The design problem click on several links on that site, and then recognize it was not the site they wanted. -

Scrolling Worse Than Tabs, Menus, and Collapsible Fieldsets

Navigation in Long Forms on Smartphones: Scrolling worse than Tabs, Menus, and Collapsible Fieldsets Johannes Harms, Martina Kratky, Christoph Wimmer, Karin Kappel, Thomas Grechenig INSO Research Group, Vienna Univ. of Technology, Austria. [firstname].[lastname]@inso.tuwien.ac.at Abstract. Mobile applications provide increasingly complex functionality through form-based user interfaces, which requires effective solutions for navi- gation on small-screen devices. This paper contributes a comparative usability evaluation of four navigation design patterns: Scrolling, Tabs, Menus, and Col- lapsible Fieldsets. These patterns were evaluated in a case study on social net- work profile pages. Results show that memorability, usability, overview, and subjective preference were worse in Scrolling than in the other patterns. This indicates that designers of form-based user interfaces on small-screen devices should not rely on Scrolling to support navigation, but use other design patterns instead. Keywords. Navigation; Mobile; Smartphone; Form Design; Evaluation 1 Introduction Forms are widely employed as user interfaces (UIs) for data entry and subsequent editing [15, 17, 22]. Long forms are often considered a bad design practice – e.g., an empirical study [22, p. 294] and recent guidelines [3] recommend against long forms and unnecessary questions. But they cannot always be avoided due to complex appli- cation requirements [16]. This also holds for forms on small-screen, mobile devices such as smartphones. Examples of mobile apps with long form-based UIs include editing a contact in the iOS address book (43 form fields), Facebook’s mobile profile page (11 collapsible fieldsets for 88 form fields), and the Samsung Galaxy system settings (4 tabs for about 380 form fields). -

Copy of Google Sitemap App

Copy of Google Sitemap app The Google Sitemap app creates an XML Sitemap file that lists URLs for each page. Sitemaps are used to tell search engines which pages they should index. This improves search engine optimization (SEO) by ensuring that all site pages are found and indexed. This is particularly important for sites that use dynamic access to content such as Adobe Flash and for sites that have JavaScript menus that do not include HTML links. Where navigation is built with Flash, a search engine will probably find the site homepage automatically, but may not find subsequent pages unless they are provided in a Google Sitemap format. Note that using Google Sitemaps does not guarantee that all links will be crawled, and even crawling does not guarantee indexing. Nevertheless, a Google Sitemap is still the best insurance for visibility in search engines. Webmasters can include additional information about each URL, such as when it was last updated, how often it changes, and how important it is in relation to other URLs in the site. Google Sitemaps adhere to the Sitemaps protocol and are ready to be submitted to search engines. Creating a sitemap Editing sitemap entries Editing virtual URI entries Publishing Viewing the sitemap Adding to robots.txt file Submitting to search engines Creating a sitemap To create a new sitemap, in Google Sitemaps (browser subapp): Click Add sitemap. You can also arrange your sitemaps in folders. In Site Map Properties: Name: The internal name of the sitemap. URI: The URI that renders the sitemap. Include Virtual URIs: Select to include any defined virtual URIs.