Top Cover and Global Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Jurisdiction in OSHA, Region 10 Version 2018.2

Guide to Jurisdiction in OSHA, Region 10 Version 2018.2 General Principles - Federal civilian employers are covered by OSHA throughout the four-state region. State, county, municipal and other non-federal public employers (except tribal government employers) are covered by state programs in Washington, Oregon, and Alaska. There is no state program in Idaho, and OSHA’s coverage of public employers in Idaho is limited to the federal sector. OSHA regulates most private employers in Idaho with exceptions noted below. Industry / Location State Coverage OSHA Coverage Air Carriers1 Washington, Oregon and Alaska: Air Washington, Oregon and Alaska: carrier operations on the ground only. Aircraft cabin crewmembers’ exposures to only hazardous chemicals (HAZCOM), bloodborne pathogens, noise, recordkeeping, and access to employee exposure and medical records. Idaho: Air carrier operations on the ground. Aircraft cabin crewmembers’ exposures to only hazardous chemicals (HAZCOM), bloodborne pathogens, noise, recordkeeping, and access to employee exposure and medical records. Commercial Diving Washington, Oregon and Alaska: Washington, Oregon, and Alaska: Employers with diving operations staged Employers with diving operations from shore, piers, docks or other fixed staged from boats or other vessels afloat locations. on navigable waters 2. Idaho: All diving operations for covered employers. 1 The term “air carrier refers to private employers engaged in air transportation of passengers and/or cargo. The term “aircraft cabin crew member” refers to employees working in the cabin during flight such as flight attendants or medical staff; however, the term does not include pilots. 2 In the state of Washington, for vessels afloat, such as boats, ships and barges moored at a pier or dock, DOSH’s jurisdiction ends at the edge of the dock or pier and OSHA’s jurisdiction begins at the foot of the gangway or other means of access to the vessel; this principle applies to all situations involving moored vessels, including construction, longshoring, and ship repair. -

Merry Christmas & Happy New Year

SOLVANG LODGE 457 WESTBY, WISCONSIN Sons of Norway Newsletter (Sandhetter) Editor: David Torgerson Volume 50 Issue #4 Westby, W December 25, 2018 MERRY CHRISTMAS & HAPPY NEW YEAR I NOT ONLY REMBER 2018, BUT THE 1950S 1950S CHRISTMAS CARD FROM YOUR EDITOR SOLVANG LODGE SEPTEMBER 25, 2018 MEETING Solvang Lodge 5-457 met at the Bekkum Library Community room on September 25, 2018 with 53 people in attendance. Corky Olson reported on the resent District 5 Convention held in La Crosse. There are funds available for flood damaged suffered by SON members with a 1- page application and at least a 1- year membership. Our lodge made a donation to The Bethel Butikk to be used for area flood victims. Karen Hankee is collecting family stories of the early Norwegian Settlers as they interacted with the Native Americans living in this area at that time, she will share these with people in Norway preparing a program on this subject. If you have a family story you would like to share, contact Karen. We acknowledged the passing of a longtime SON member Trygve Ostrem. Dennis Hagen won the Pot ‘O gold. Our program for the evening was presented by a very knowledgeable and talented wood carver Judy Gates. She had samples of the many different styles of carving and the varieties of wood used. We were told that “if you can peal a potato you can carve in wood.” A “whittler” uses a knife, a “carver” uses many different tools, of which she had samples. There will be a “Carve In” to be held on April 27, 2019 in the Bekkum Library Community Room. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Federal Register/Vol. 78, No. 193/Friday, October 4, 2013/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 78, No. 193 / Friday, October 4, 2013 / Notices 61851 11. Type of Information Collection this collection contact Anitra Johnson at would constitute a clearly unwarranted Request: Reinstatement without change 410–786–0609). invasion of personal privacy. of a previously approved collection; 13. Type of Information Collection Name of Committee: National Human Title of Information Collection: Request: Extension of a currently Genome Research Institute Special Emphasis Medicare Geographic Classification approved collection; Title of Panel Extramural Gene Function Research Review Board (MGCRB) Procedures and Information Collection: State Children’s Initiative (R21) UDP. Supporting Regulations; Use: The Health Insurance Program and Date: November 27, 2013. information submitted by the hospitals Supporting Regulations; Use: States Time: 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. is used to determine the validity of the must submit title XXI plans and Agenda: To review and evaluate grant hospitals’ requests and the discretion amendments for approval by the applications. Secretary. We use the plan and its Place: National Human Genome Research used by the Medicare Geographic Institute, 4076 Conference Room, 5635 Classification Review Board (MGCRB) subsequent amendments to determine if Fishers Lane, Rockville, MD 20852, in reviewing and making decisions the state has met the requirements of (Telephone Conference Call). regarding hospitals’ requests for title XXI. Information provided in the Contact Person: Keith McKenney, Ph.D., geographic reclassification. Form state plan, state plan amendments, and Scientific Review Officer, NHGRI, 5635 Number: CMS–R–138 (OCN: 0938– from the other information we are Fishers Lane, Suite 4076, Bethesda, MD 0573); Frequency: Yearly; Affected collecting will be used by advocacy 20814, 301–594–4280, mckenneyk@ Public: Business or other for-profits and groups, beneficiaries, applicants, other mail.nih.gov. -

Decision Analysis Methodology to Evaluate Integrated Solid Waste Management Alternatives for a Remote Alaskan Air Station

Air Force Institute of Technology AFIT Scholar Theses and Dissertations Student Graduate Works 3-2001 Decision Analysis Methodology to Evaluate Integrated Solid Waste Management Alternatives for a Remote Alaskan Air Station Mark J. Shoviak Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.afit.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Shoviak, Mark J., "Decision Analysis Methodology to Evaluate Integrated Solid Waste Management Alternatives for a Remote Alaskan Air Station" (2001). Theses and Dissertations. 4696. https://scholar.afit.edu/etd/4696 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Graduate Works at AFIT Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AFIT Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DECISION ANALYSIS METHODOLOGY TO EVALUATE INTEGRATED SOLID WASTE MANAGMENT ALTERNATIVES FOR A REMOTE ALASKAN AIR STATION THESIS Mark J. Shoviak, Captain, USAF AFIT/GEE/ENV/01M-20 DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED. The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U. S. Government. AFIT/GEE/ENV/01M-20 DECISION ANALYSIS METHODOLOGY TO EVALUATE INTEGRATED SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT ALTERNATIVES FOR A REMOTE ALASKAN AIR STATION THESIS Presented to the Faculty Department of Systems and Engineering Management Graduate School of Engineering and Management Air Force Institute of Technology Air University Air Education and Training Command In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering and Environmental Management Mark J. -

Defending Attack from the North: Alaska's Forward Operating Bases

DEFENDING ATTACK FROM THE NORTH: Alaska’s Forward Operating Bases During the Cold War Photo: Eleventh Air Force History Office Archives DDTTACKEFENDING FROMATTACK THE NORTH FROM: THE NORTH: Alaska’s Forward Operating Bases During the Cold War The Alaskan forward operating bases (FOBs) played a significant role in the United States’ strategic air defense in the early Cold War. Because the Alaskan FOBs were located close to the Soviet Union, and more importantly, close to Soviet bases used for bomber opera- tions, the fighters stationed there could and Must Watch Both North and West did intercept the major share of Soviet aircraft that ventured into American airspace. This booklet presents the history of the FOBs and was compiled from a variety of sources, including recently declassified military histories and interviews with veterans and long-time contractors at the installations. The Soviet Threat in the 1950s Soon after World War II, the military emphasis for U.S. forces in Alaska shifted from coun- tering a threat from the western Pacific to countering a threat from the Arctic north. The Soviet Union, which lacked access to foreign bases within bombing distance of North America, established numerous airfields in northern Siberia beginning in 1945. Because those airfields were one thousand miles closer to the heartland of the United States than any other potential military base in the U.S.S.R. and because Soviet bombers lacked adequate range to attack from other bases, the Siberian bases represented the most significant threat This map created and published by the 49th Star newspaper illus- of Soviet attack on North America. -

AFA National Report [email protected] by Frances Mckenney, Assistant Managing Editor

AFA National Report [email protected] By Frances McKenney, Assistant Managing Editor Think Big, Plan Big The Frank Luke Chapter hosted the Southwest Region Conference in Litchfield Park, Ariz., with AFA repre- sentatives present from Arizona, New Mexico, and Nevada. The three-day event not only covered AFA regional business but also offered guest speakers and panel discussions on Air Force, space, and cyberspace topics, with a local focus. Retired Lt. Gen. John F. Regni, superintendent of the US Air Force Academy until his retirement in 2009, led the roster of speakers. He is to- day director of Science Foundation Arizona, a nonprofit based in Phoenix that encourages investment in science through administration of research, development, and education grants. Werner J. A. Dahm, a former Air Force chief scientist, was another keynote speaker. He is now director of Arizona State University’s Security and Defense AFA Board Chairman Sandy Schlitt (second from right) goes over the agenda at the Southwest Region Conference in June in Litchfield Park, Ariz. He was a keynote Systems Initiative. speaker. L-r: Karel Toohey; Southwest Region President John Toohey; Arizona State A panel of military personnel included President Ross Lampert; and Scott Chesnut, conference master of ceremonies. Brig. Gen. Jerry D. Harris Jr., commander of Luke Air Force Base’s 56th Fighter More photos at http://www.airforce-magazine.com, in “AFA National Report” Wing; Col. Jose R. Monteagudo from the 944th Fighter Wing at Luke; Col. enth annual Space and Cyberspace David D. Thompson, director of air, Kirk W. Smith from the 27th Special Warfare Symposium took place June space, and cyberspace operations Operations Wing at Cannon AFB, N.M.; 14-16 in Keystone, Colo. -

0 7 Jun 2005

DCN: 11893 THE SECRETARY OF THE AIR FORCE CHIEF OF STAFF, UNITED STATES AIR FORCE WASHINGTON DC 0 7 JUN 2005 MEMORANDUM FOR CHAIRMAN, DEFENSE BASE CLOSURE AND REALIGNMENT COMMISSION (HONORABLE ANTHONY J. PRINCIPI) SUBJECT: Department of Defense Recommendation to Realign Eielson AFB, Alaska and Grand Forks AFB, North Dakota We would like to take this opportunity to provide you information on the U.S. Air Force vision for Eielson Air Force Base (AFB), Alaska and Grand Forks AFB, North Dakota and the significant role these installations will play as the Air Force implements its Future Total Force. The Secretary of Defense accepted Air Force reco~nmendationsto realign, but not close, Eielson and Grand Forks AFBs. Our reco~mendations,while somewhat unusual as they did not permanently assign additional aircraft to these bases as part of realignment, considered the long-term military value of both installations. During our May 17,2005 testimony to your co~lltnission,we attempted to convey our vision for these bases and the important contributions they will make to the Air Force's ability to confiont the new and evolving threats of the 21" Century. Attached are two papers describing this vision more clearly. We hope you and the members of the Base Realignment and Closure Commission will find this information helpful. Chief of Staff Attaclunents: 1. Background Paper on Eielson AFB 2. Background Paper on Grand Forks AFB DCN: 11893 BACKGROUND PAPER REALIGNMENT OF EIELSON AIR FORCE BASE, ALASKA PURPOSE Provide Air Force Vision for Eielson Air Force Base (AFB) realignment and how this base will contribute to Air Force Future Total Force missions and initiatives. -

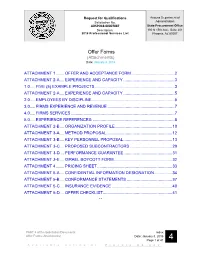

Offer Forms (Attachments) Date: January 8, 2018

Request for Qualifications Arizona Department of Solicitation No. Administration ADSPO18-00007887 State Procurement Office Description: 100 N 15th Ave., Suite 201 2018 Professional Services List Phoenix, AZ 85007 Offer Forms (Attachments) Date: January 8, 2018 ATTACHMENT 1 ........ OFFER AND ACCEPTANCE FORM ...................................... 2 ATTACHMENT 2-A .... EXPERIENCE AND CAPACITY ............................................. 3 1.0 ..... FIVE (5) EXAMPLE PROJECTS ...................................................................... 3 ATTACHMENT 2-A .... EXPERIENCE AND CAPACITY ............................................. 5 2.0 ..... EMPLOYEES BY DISCIPLINE ......................................................................... 5 3.0 ..... FIRMS EXPERIENCE AND REVENUE ........................................................... 7 4.0 ..... FIRMS SERVICES ........................................................................................... 7 5.0 ..... EXPERIENCE REFERENCES: ........................................................................ 8 ATTACHMENT 2-B .... ORGANIZATION PROFILE .................................................. 10 ATTACHMENT 3-A .... METHOD PROPOSAL .......................................................... 12 ATTACHMENT 3-B .... KEY PERSONNEL PROPOSAL ........................................... 13 ATTACHMENT 3-C ... PROPOSED SUBCONTRACTORS ..................................... 29 ATTACHMENT 3-D ... PERFORMANCE GUARANTEE ........................................... 31 ATTACHMENT 3-E .... ISRAEL -

Integrated Natural Resources Management Plan 2013

INTEGRATED NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT PLAN 2013 611th Air Support Group Alaska Installations U.S. AIR FORCE, 611th AIR SUPPORT GROUP, ALASKA 611th CIVIL ENGINEER SQUADRON, ASSESSMENT MANAGEMENT INTEGRATED NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT PLAN 2013 611th Air Support Group, Alaska Installations This revised Integrated Natural Resources Management Plan (INRMP) meets requirements of the Sikes Act (16 USC 670a et seq.) as amended and as approved in previous plans in 2007, 2008, and 2009 by the 611th Air Support Group Commander, the Alaska Regional Director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game commissioner. Use and mission of the installations have not significantly changed since approval of the previous plans. The Short and Long Range Radar Sites and Eareckson Air Station INRMPs were approved for use in 2007; the King Salmon Airport INRMP was approved for use in 2008; and the Inactive Sites INRMP was approved for use in 2009. They will remain in use until replaced by the final version of this plan. The primary change in this revised INRMP is that of format to follow guidance provided in Air Force Instruction 32-7064. This INRMP also groups installations from the four previous plans into one document. Data specific to each installation and management goals, objectives, and projects have also been updated and included in this revision. Sikes Act Cooperating Agencies* ROBYN M. BURK, Colonel, USAF Commander 611th Air Support Group GEOFFREY HASKETT Regional Director, Region 7 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service *Above signatures are digital copies of originals, which are on file at the 611th Air Support Group. -

Pinnacle 19-1 Bio Book.Pdf

BBIIOOGGRRAAPPHHIICCAALL DDAATTAA BBOOOOKK Pinnacle 19-1 25-29 March 2019 National Defense University SENIOR FELLOWS Admiral Sam J Locklear, US Navy (Ret) Admiral Locklear started as a Capstone, Keystone, Pinnacle Senior Fellow in 2019. He is President of SJL Global Insights LLC, a global consulting firm specializing in a wide range of security and defense issues and initiatives. Today he serves on the Board of Directors of the Fluor Corporation, Halo Maritime Defense Systems, Inc., the National Committee on U.S. China Relations, is a Senior Advisor to the Center for Climate and Security and New York University’s Center for Global Affairs, is a Senior Fellow at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, and is the Chairman of the Board of Trustees United States Naval Academy Alumni Association. He also occasionally consults for HII, Raytheon IDS, and Fairfax National Security Solutions. In 2015 he retired from the US Navy after serving with distinction for over 39 years, including 15 years of service as a Flag Officer. During his significant tenure Admiral Locklear lead at the highest levels serving as Commander U.S. Pacific Command, Commander U.S. Naval Forces Europe and Africa, and Commander of NATO’s Allied Joint Force Command. In 2013 Defense News ranked him eleventh out of the 100 most influential people in global defense issues. As Commander U.S. Pacific Command, the United States’ oldest and largest geographic unified combatant command, he commanded all U.S. military forces operating across more than half the globe. He accurately assessed the rapidly changing geopolitical environment of the Indo-Asia-Pacific, the most militarized area of the world, made significant advancements in how U.S. -

Fy18 Ballistic Missile Defense Systems

Director, Operational Test and Evaluation FY 2018 Annual Report December 2018 This report satisfies the provisions of Title 10, United States Code, Section 139. The report summarizes the operational test and evaluation activities (including live fire testing activities) of the Department of Defense during the preceding fiscal year. Robert F. Behler Director FY18 INTRODUCTION FY 2018 Annual Report The freedom and security of our nation depends on the lethality and readiness of our military. Our warfi ghters must be prepared for combat, equipped with secure, credible weapon systems, and trained to employ those systems eff ectively and decisively. As the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E), I ensure that our weapon systems are systematically tested across a range of operational conditions that warfi ghters are likely to encounter in combat. Establishing combat credibility through realistic testing gives warfi ghters the confi dence their weapons and equipment will work when they need them. I have been in this position for just over one year and, during this time, have informed 92 acquisition and 25 fi elding decisions for the Department. When I was appointed to this position, I committed to increasing collaboration between DOT&E and other agencies within the defense community. Looking back, I have been most impressed with the “spirit of cooperation” between OSD and the military Services. With an attitude of teamwork, we are working towards the ability to fi eld combat credible systems at the speed of relevance. During the past year, my offi ce collaborated with other OSD offi ces and the test and evaluation (T&E) community to increase combined approaches to testing programs.