2 MB 9Th Apr 2021 BBC Ideas Full Report [Final]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liverpool Capstone Theatre 25 June 2015 What’S Thepoint? Summer Shows for Year 9S and 10S

Liverpool Capstone Theatre 25 June 2015 what’s thePOINT? Summer ShowS for Year 9s and 10s A fantastic outing, all our students enjoyed it Maths Teacher, South Liverpool mathsinspiration.com what’s Matt Parker is known as the ‘stand-up mathematician’ and is the only person thePOINT? to hold the prestigious title of London SUMMER SHOWS FOR YEAR 9s AND 10s Mathematical Society Popular Lecturer while simultaneously having a sold-out comedy show at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. A regular on Liverpool Capstone Theatre Numberphile, Matt is always keen to mix his two passions of Thurs 25 June 2015, mathematics and stand-up as well as presenting TV and 10.30am–12.30pm & 1.30pm–3:30pm radio shows. Rob Eastaway is an author whose Tickets: £7.50 (inc VAT). For each 10 student ticket books on everyday maths include the purchases we include a free Teacher ticket. bestselling Why Do Buses Come In Threes? and The Hidden Maths of Sport. Inspire your Year 9s and 10s – even the ones who He appears regularly on BBC Radio 4 and don’t love maths – with a lecture show featuring 5 Live to talk about the maths of everyday life and has given some of the country’s most entertaining maths maths talks around the world to audiences of all ages. speakers. Hannah Fry is a mathematician at Do your students wonder what’s the point of University College London (or ‘Mathmo at algebra? Who on earth needs Pythagoras? UCL’ for short) as well as being an author and science presenter. You can find her And who cares about exponentials? on YouTube, TV and radio sharing her In this highly engaging and interactive show Matt Parker, love of applied mathematics and exploring the patterns it Rob Eastaway and Hannah Fry (plus special guest) explain reveals in our human behaviour. -

Drama Drama Documentary

1 Springvale Terrace, W14 0AE Graeme Hayes 37-38 Newman Street, W1T 1QA SENIOR COLOURIST 44-48 Bloomsbury Street WC1B 3QJ Tel: 0207 605 1700 [email protected] Drama The People Next Door 1 x 60’ Raw TV for Channel 4 Enge UKIP the First 100 Days 1 x 60’ Raw TV for Channel 4 COLOURIST Cyberbully 1 x 76’ Raw TV for Channel 4 BAFTA & RTS Nominations Playhouse Presents: Foxtrot 1 x 30’ Sprout Pictures for Sky Arts American Blackout 1 x 90’ Raw TV for NGC US Blackout 1 x 90’ Raw TV for Channel 4 Inspector Morse 6 x 120’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 Poirot’s Christmas 1 x 100’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 The Railway Children 1 x 100’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 Taking the Flak 6 x 60’ BBC Drama for BBC Two My Life as a Popat 14 x 30’ Feelgood Fiction for ITV 1 Suburban Shootout 4 x & 60’ Feelgood Fiction for Channel 5 Slap – Comedy Lab 8 x 30’ World’s End for Channel 4 The Worst Journey in the World 1 x 60’ Tiger Aspect for BBC Four In Deep – Series 3 4 x 60’ Valentine Productions for BBC1 Drama Documentary Nazi Megaweapons Series III 1 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Metropolis 1 x 60’ Nutopia for Travel Channel Million Dollar Idea 2 x 60’ Nutopia Hostages 1 x 60’ Al Jazeera Cellblock Sisterhood 3 x 60’ Raw TV Planes That Changed the World 3 x 60’ Arrow Media Nazi Megaweapons Series II 1 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Dangerous Persuasions Series II 6 x 60’ Raw TV Love The Way You Lie 6 x 60’ Raw TV Mafia Rules 1 x 60’ Nerd Nazi Megaweapons 5 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Breakout Series 2 10 x 60’ Raw TV for NGC Paranormal Witness Series 2 12 x 60’ Raw TV -

Progressive Nationalism Citizenship and the Left

As ties of religion, class and ethnicity weaken, national identity may be the best way to preserve the Left’s collective ideals… Progressive Nationalism Citizenship and the Left David Goodhart About Demos Who we are Demos is the think tank for everyday democracy. We believe everyone should be able to make personal choices in their daily lives that contribute to the common good. Our aim is to put this democratic idea into practice by working with organisations in ways that make them more effective and legitimate. What we work on We focus on six areas: public services; science and technology; cities and public space; people and communities; arts and culture; and global security. Who we work with Our partners include policy-makers, companies, public service providers and social entrepreneurs. Demos is not linked to any party but we work with politicians across political divides. Our international network – which extends across Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, Australia, Brazil, India and China – provides a global perspective and enables us to work across borders. How we work Demos knows the importance of learning from experience. We test and improve our ideas in practice by working with people who can make change happen. Our collaborative approach means that our partners share in the creation and ownership of new ideas. What we offer We analyse social and political change, which we connect to innovation and learning in organisations.We help our partners show thought leadership and respond to emerging policy challenges. How we communicate As an independent voice, we can create debates that lead to real change.We use the media, public events, workshops and publications to communicate our ideas. -

Keep on Learning in Maths!

Keep on learning in Maths! Are you enjoying your maths work? Are you looking for something more? Are you in Year 11 and considering maths for A-Level? This is the place for you! We have tried to put together some ideas for you to extend your mathematical knowledge beyond what MyMaths and Kerboodle. None of this work is compulsory and we will not be assessing it, BUT if you have a go at it and want to share your work then please do! We would love to hear from you all Year 7 ● Have a go at some of the MyMaths games. They can be found on the left hand side menu under Activities. The games are split into Number, Algebra, Shape and Data so you can pick different ones to play. Challenge your friends! ● Some more challenging mathematical games can be found here: https://nrich.maths.org/9465. I particularly liked Last Biscuit ● Watch a documentary or a TED talk about applied maths- a list is attached at the bottom of this document Year 8 ● Have a go at some of the MyMaths games. They can be found on the left hand side menu under Activities. The games are split into Number, Algebra, Shape and Data so you can pick different ones to play. Challenge your friends! ● Nrich have a number of short problems here https://nrich.maths.org/11993 ● Watch a documentary or a TED talk about applied maths- a list is attached at the bottom of this document Year 9 ● Do you enjoy things like Sudoku? Then the game 2048 might be the one for you! You can download it onto your phone or go to https://2048game.com/ to play ● Some challenging maths problems and games here https://wild.maths.org/. -

“Britain Should Pay Reparations for ITS Role in the Slave Trade”

MOTION: JANUARY 2016 REPARATIONS “BRITAIN SHOULD NADIA BUTT PAY REPARATIONS FOR ITS ROLE IN THE SLAVE TRADE” DEBATING MATTERS DEBATOPITING MATTERCS GUIDETOPICS GUIDEwww.debatingmatters.comS ABOUT DEBATING MATTERS SUPPORTED BY Debating Matters because ideas PRIMARY FUNDER HEADLINE PRIZE SPONSOR matter. This is the premise of the Institute of Ideas Debating Matters Competition for sixth form students which emphasises substance, not just style, and the importance of taking ideas seriously. Debating Matters REGIONAL SPONSORS presents schools with an innovative and engaging approach to debating, where the real-world debates and a challenging format, including panel judges who engage with the students, CHAMPIONS REGIONAL FINAL SPONSOR appeal to students from a wide range of backgrounds, including schools with a long tradition of debating and those with none. VENUE PARTNERS process cyan pantone 7545U CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 of 6 NOTES Despite The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 formally outlawing Introduction 1 slavery throughout the British Empire nearly 200 years ago [Ref: Wikipedia], Prime Minister David Cameron’s first state visit to Key terms 1 Jamaica last September was overshadowed by calls from high- The Reparations debate in context 2 profile politicians, including Jamaican leader Portia Simpson Miller, for Britain to pay reparations for its involvement in the Essential reading 4 slave trade [Ref: RT]. This is just one example of an increasing Backgrounders 5 demand for reparations from Western nations to individuals and countries who were affected by the slave trade. According to Organisations 5 some calculations, reparations for the transatlantic slave trade [Ref: UNESCO] could add up to $14 trillion [Ref: Newsweek] and Audio/Visual 6 those calling for reparations argue that slavery facilitated the In the news 6 rise of Britain as a global player, and forced human exploitation was a “major source of wealth of the British Empire” [Ref: Independent]. -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 11 – 17 August 2012

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 11 – 17 August 2012 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 11 AUGUST 2012 SAT 04:00 EM Forster Short Stories (b017gvd8) SAT 18:30 Fantastic Journeys (b00h73hy) The Road From Colonus The Door in the Wall by HG Wells SAT 00:00 Charles Chilton - Journey into Space Mr Lucas's tiresome family thwart his plans for a sojourn in the Daydreamer Lionel Wallace’s encounters with an unlocked door (b007jmsm) idyllic Greek countryside. Read by Andrew Sachs. as a young child continue to prey on his mind as an adult. Operation Luna SAT 04:15 Paupers and Pig Killers (b007jx3z) At different times in his life, the door temptingly reappears. But 4. Is There Anybody Out There? Series 1 when a golden opportunity arrives, is Lionel brave enough to Captain Jet Morgan and his crew face catastrophe when their The Troubles of This Life turn his back on the world he knows for a better life? rocket loses power. The lively events in the parish of Over Stowey, from the 1799 Anton Lesser reads HG Wells' story. Written and produced by Charles Chilton. diary of Somerset parson, William Holland. Stars Ronald Some of the best sci-fi/fantasy writers in a series of fantastic Jet Morgan …. Andrew Faulds Pickup. journeys featuring flights of fancy, time travel, magical Lemmy Barnett …. Alfie Bass SAT 05:00 Beachcomber... By the Way (b007jqgs) transporters and alternate realities. Doc …. Guy Kingsley-Poynter Series 2 Abridged and produced by Gemma Jenkins. Mitch …. David Williams Episode 5 Made for BBC Radio 7 and first broadcast in February 2009. -

For the Curious Mind. Be Part of It

For the curious mind. Be part of it. ProsPect – good writing about the things that matter Prospect breaks the mould of modern-day journalism. it covers a broad range of topics from current affairs to culture and business to science and technology. every month Prospect combines elegant design with a strikingly original mix of essays, opinion, debate and reviews. What sets it apart is its intellectual depth. Each issue brings together the sharpest minds to unravel the complexities of events and ideas that define the modern world. Politically, Prospect is neither left nor right. Its views are those of its opinionated mix of editors and contributors who write for an audience keen to participate in the debate, but who will ultimately make up their own mind. The result is an entertaining, informative and open minded magazine that mixes compelling argument and clear headed analysis with an international style. ❝Prospect offers intellectual discovery when everything else is going in the opposite direction.❞ david goodhart, editor, prospect. our editorial Prospect is britain’s foremost monthly commentary on current affairs, epitomising long-form journalism at its best. Features Nothing is off limits to our feature writers. What is certain is that this section combines breadth of coverage with thoughtful, unpredictable and eclectic comment. This is in-depth reading at its best – probing to awaken the curious mind. opinions Thought provoking, often intellectual, always surprising, these articles are written by leading thinkers and opinion formers. science and technology things to do this month The story behind the headlines, across a Our pick of what to see and do this month – mix of subjects, from hard sciences through from the popular to the obscure, this new section consumer technology and media. -

Maths Resources for Schools

Maths Resources for Schools Resources for students Key Resource stage Additional Reading ALL Internet Archive has millions of free books, movies, websites and more. KS5 Worcester College Bookshelf Project Maths “Closing the Gap: The Quest to Understand Prime Numbers - Vicky Neale” KS5 Staircase 12 KS4-5 Maths questions set by Oxford tutors. KS5 Bridging Material • Alcock, Lara How to Study for a Mathematics Degree (2012) • Allenby, Reg Numbers and Proofs (1997) • Earl, Richard Towards Higher Mathematics: A Companion (2017) • Houston, Kevin How to Think Like a Mathematician (2009) • Liebeck, Martin A Concise Introduction to Pure Mathematics (2000) Popular Mathematics • Acheson, David 1089 and All That (2002), The Calculus Story (2017) • Bellos, Alex Alex’s Adventures in Numberland (2010) • Clegg, Brian A Brief History of Infinity (2003) • Courant, Robbins and Stewart What is Mathematics? (1996) • Devlin, Keith Mathematics: The New Golden Age (1998), The Millennium Problems (2004), The Unfinished Game (2008) • Dudley, Underwood Is Mathematics Inevitable? A Miscellany (2008) • Elwes, Richard MATHS 1001 (2010), Maths in 100 Key Breakthroughs (2013) • Gardiner, Martin The Colossal Book of Mathematics (2001) • Gowers, Tim Mathematics: A Very Short Introduction (2002) • Hofstadter, Douglas Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid (1979) • Körner, T. W. The Pleasures of Counting (1996) • Neale, Vicky Closing the Gap: the quest to understand prime numbers (2017) • Odifreddi, Piergiorgio The Mathematical Century: The 30 Greatest Problems of -

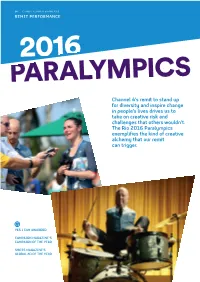

Statement of Media Content Policy 2016.Pdf

14 CHANNEL 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 REMIT PERFORMANCE 2016 PARALYMPICS Channel 4’s remit to stand up for diversity and inspire change in people’s lives drives us to take on creative risk and challenges that others wouldn’t. The Rio 2016 Paralympics exemplifies the kind of creative alchemy that our remit can trigger. YES I CAN AWARDED: CAMPAIGN MAGAZINE’S CAMPAIGN OF THE YEAR SHOTS MAGAZINE’S GLOBAL AD OF THE YEAR CHANNEL 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 15 2/3 48% OF OUR ON-AIR PRESENTING OF THE UK POPULATION TEAM WERE DISABLED. REACHED WITH OUR PARALYMPIC COVERAGE London 2012 was a watershed moment for Paralympic sport, and the Rio 2016 Paralympics went even further in raising >40m 1.8m the profile of disability sport and positively VIEWS ACROSS ALL SOCIAL APPEARING IN HALF OF THE PLATFORMS. UK’S FACEBOOK FEEDS AND improving public perceptions of disability in WITH OVER 1.8 MILLION SHARES, the UK and around the world. ‘YES I CAN’ WAS THE MOST SHARED OLYMPIC/PARALYMPIC It also established a new international AD GLOBALLY THIS YEAR. benchmark for Paralympics coverage. The UK is now considered an exemplar for its approach to the Games by the International Paralympic Committee and Channel 4 has shared this success story with broadcasters around the world since the 2012 Games. Preparing for Rio 2016 following the success of London 2012 was no small order, however we saw it as more of an opportunity than a risk – because taking creative risks pushes The result was a three-minute film featuring OUR RIO COVERAGE boundaries in the pursuit of positive change, 140 disabled people with a band specifically Taking on the ratings challenge of an away which is part of Channel 4’s DNA. -

Decolonising the University

Decolonising the University Decolonising the University Edited by Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial and Kerem Nişancıoğlu First published 2018 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial and Kerem Nişancıoğlu 2018 The right of the individual contributors to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3821 7 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3820 0 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7868 0315 3 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0317 7 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0316 0 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America Bhambra.indd 4 29/08/2018 17:13 Contents 1 Introduction: Decolonising the University? 1 Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial and Kerem Nişancıoğlu PART I CONTEXTS: HISTORICAL AND DISCPLINARY 2 Rhodes Must Fall: Oxford and Movements for Change 19 Dalia Gebrial 3 Race and the Neoliberal University: Lessons from the Public University 37 John Holmwood 4 Black/Academia 53 Robbie Shilliam 5 Decolonising Philosophy 64 Nelson Maldonado-Torres, Rafael Vizcaíno, Jasmine Wallace and Jeong Eun Annabel We PART II INSTITUTIONAL INITIATIVES 6 Asylum University: Re-situating Knowledge-exchange along Cross-border Positionalities 93 Kolar Aparna and Olivier Kramsch 7 Diversity or Decolonisation? Researching Diversity at the University of Amsterdam 108 Rosalba Icaza and Rolando Vázquez 8 The Challenge for Black Studies in the Neoliberal University 129 Kehinde Andrews 9 Open Initiatives for Decolonising the Curriculum 145 Pat Lockley vi . -

Give and Take: How Conservatives Think About Welfare

How conservatives think about w elfare Ryan Shorthouse and David Kirkby GIVE AND TAKE How conservatives think about welfare Ryan Shorthouse and David Kirkby The moral right of the authors has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. Bright Blue is an independent think tank and pressure group for liberal conservatism. Bright Blue takes complete responsibility for the views expressed in this publication, and these do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors. Director: Ryan Shorthouse Chair: Matthew d’Ancona Members of the board: Diane Banks, Philip Clarke, Alexandra Jezeph, Rachel Johnson First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Bright Blue Campaign ISBN: 978-1-911128-02-1 www.brightblue.org.uk Copyright © Bright Blue Campaign, 2014 Contents About the authors 4 Acknowledgements 5 Executive summary 6 1 Introduction 19 2 Methodology 29 3 How conservatives think about benefit claimants 34 4 How conservatives think about the purpose of welfare 53 5 How conservatives think about the sources of welfare 66 6 Variation amongst conservatives 81 7 Policies to improve the welfare system 96 Annex one: Roundtable attendee list 112 Annex two: Polling questions 113 Annex three: Questions and metrics used for social and economic conservative classification 121 About the authors Ryan Shorthouse Ryan is the Founder and Director of Bright Blue. -

SCIENCE GALLERY DUBLIN ANNUAL REVIEW 01.01.14– 31.12.14 Total Visitors

SCIENCE GALLERY DUBLIN ANNUAL REVIEW 01.01.14– 31.12.14 Total Visitors 2014 — 406,982 2013 — 339,264 2012 — 302,171 2011 — 242,833 2010 — 203,619 3— HazMat Suits for Children Visitors during our busiest week of the year Total followers on Facebook 2014 — 11,966 2014 — 29,102 2013 — 12,239 2013 — 13,353 2012 — 10,983 2012 — 6,260 2011 — 7,576 2011 — 3,924 2010 — 3,907 2010 — 1,879 1— famous Olympian, Sonia O’Sullivan, sharing her fail tale “Listening to Sonia O’Sullivan’s view of her Atlanta misfire was a revelation” — The Irish Times 1,338— futuristic weather forecasts recorded in front of our green screen SCIENCE GALLERY DUBLIN ANNUAL REVIEW 01.01.14– 31.12.14 National broadcast coverage (AVE Total followers on Twitter National Print Media Coverage (AVE) ) 2014 — €2,654,615 2014 — € 1,380,753 2014 — 24,653 2013 — €1,960,887 2013 — €1,202,832 2013 — 20,681 2012 — €2,578,179 2012 — €1,158,220 2012 — 14,980 2011 — €1,872,299 2011 — €274,999 2011 — 8,751 —metres400 of #FAILBETTER tweets produced by our 2010 — 2,252,573 2010 — 318,998 2010 — 4,381 € € Twitter printer National Print Media Coverage (cm2) “Awesome exhibit in science gallery called #FAILBETTER. Highlight was birthing apparatus that uses centrifugal —1 patent (Apparatus for Facilitating the Birth of a Child by Centrifugal 2014 — 259,764 force.” — @ZipLockBagMan Force) brought to life for the very fi rst time 2013 — 213,747 2012 — 245,130 2011 — 166,318 2010 — 290,430 150— national broadcast pieces — musicians thrilling the crowd from the stage at FAIL BIG 564— national print media