Conditions Leading to the Adoption of the National Guard Youth Challenge Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Catalog Master List

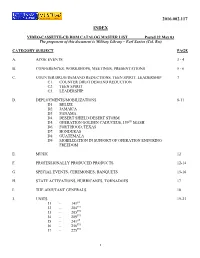

2016.002.117 INDEX VIDEO-CASSETTE-CD ROM CATALOG MASTER LIST Posted 22 May 03 The proponent of this document is Military Library – Earl Santos (Col. Ret) CATEGORY SUBJECT PAGE A. ACOE EVENTS 3 - 4 B. CONFERENCES, WORKSHOPS, MEETINGS, PRESENTATIONS 5 - 6 C. COUNTER DRUG/DEMAND REDUCTIONS, TEEN SPIRIT, LEADERSHIP 7 C1. COUNTER DRUG DEMAND REDUCTION C2. TEEN SPIRIT C3. LEADERSHIP D. DEPLOYMENTS/MOBILIZATIONS 8-11 D1. BELIZE D2. JAMAICA D3. PANAMA D4. DESERT SHIELD/DESERT STORM D5. OPERATION GOLDEN CADUCEUS, 159TH MASH D6. FORT HOOD, TEXAS D7. HONDURAS D8. GUATEMALA D9 MOBILIZATION IN SUPPORT OF OPERATION ENDURING FREEDOM E. MUSIC 12 F. PROFESSIONALLY PRODUCED PRODUCTS 12-14 G. SPECIAL EVENTS, CEREMONIES, BANQUETS 15-16 H. STATE ACTIVATIONS, HURRICANES, TORNADOES 17 I. THE ADJUTANT GENERALS 18 J. UNITS 19-23 J1 - 141ST J2 - 204TH J3 - 205TH J4 - 209TH J5 - 241ST J6 - 256TH J7 - 225TH 1 2016.002.117 J8 - 5TH ARMY J9 - 528th J10 - 1083rd J11 - 527th J12 - 244THAA J13 - 812th J14 - 61st TROOP COMMAND J15 - 769th J16 - 1/156th INFANTRY J17 - 2/156TH INFANTRY J18 - 159 ARMY BAND J19 - 159 MASH J20 - 773 TANK DESTROYER BN K. WW II 24-25 L. YOUTH CHALLENGE PROGRAM (YCP) 26-27 M. JACKSON BARRACKS MILITARY HISTORY 28-29 M1. -JACKSON BARRACKS MILITARY MUSEUM, NOLA M2. -JACKSON BARRACKS MILITARY LIBRARY, NOLA M3. -JACKSON BARRACKS, NOLA M4. -CAMP BEAUREGARD MILITARY MUSEUM, PINEVILLE, LA M5. -GILLIS W. LONG CENTER, CARVILLE, LA N. AIR NATIONAL GUARD 30 O. COMMUNITY PROJECTS 31-32 O1 - GUARD CARE O2 - CLEAN SWEEP O3 - MAISON ORLEANS O4 - UNITED WAY O5 - SPECIAL OLYMPICS O6 - REEF-EX O7 - CHRISTMAS TREE RECYCLING O8 - EMPLOYER SUPPORT GUARD RESERVE (ESGR) O9 - D-DAY PARADE P. -

Department of Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies Executive Summary

Department of Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies Executive Summary http://wgss.ku.edu A. Mission Founded in 1972, the Department of Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies fosters the interdisciplinary study of women, gender, and sexuality through a rich multicultural and internationally informed academic environment, and affirms social justice for all persons, academic freedom and integrity, intellectual community, interdisciplinary inquiry, critical engagement, global justice, and diversity. B. Faculty The nine core faculty members represent a diversity of ethnicities, nationalities, sexual identities, and disciplines with PhDs in Anthropology, Classics, English, History, Psychology, Political Science, and Women's Studies. In addition, some 40 Courtesy Faculty members from almost every unit in the University contribute 45 courses to WGSS programs. All our core faculty are nationally and internationally known scholars and excellent teachers, some receiving the highest awards for their research and teaching. Details for the core faculty are in their CVs, but here are some highlights: Ajayi-Soyinka: African literature, choreography and theater. Britton: gender and African politics. Hart: public health and medicine. Muehlenhard: sexual coercion and consent. Saraswati: race, skin color, and gender in transnational Indonesia. Schofield: class, gender, and work in the US. Takeyama: the commercialization of intimate relationships in contemporary Japan. Vicente; the history of women in early modern Europe. Υounger: sexual behaviors and attitudes in ancient Greece and Rome. C. Programs Undergraduate: WGSS offers a BA and BGS in Women's Studies and a minor in Women's Studies and in Human Sexuality. These programs each require an introductory course and an interdisciplinary balance between the social sciences and humanities, while the major includes theory, an international course, and a capstone research experience. -

Evaluation of the National Guard Youth Challenge/Job Challenge Program, Final Report

Final Report Evaluation of the National Guard Youth ChalleNGe / Job ChalleNGe Program May 22, 2020 Jillian Berk, Ariella Kahn-Lang Spitzer, Jillian Stein, and Karen Needels (Mathematica) Christian Geckeler, Anne Paprocki, and Ivette Gutierrez (Social Policy Research Associates) Megan Millenky (MDRC) Submitted to: Submitted by: U.S. Department of Labor Mathematica Chief Evaluation Office 1100 First Street, NE 200 Constitution Ave, NW Suite 1200 Washington, DC 20210 Washington, DC 20002-4221 Project Officer: Jennifer Daley Phone: (202) 484-9220 Contract Number: DOLQ129633249/ Project Director: Jillian Berk DOL-OPS-15-U-00089 Reference Number: 50120.340 This page has been left blank for double-sided copying. Job ChalleNGe Final Report Mathematica Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. xi I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1 A. The Youth ChalleNGe program model and Job ChalleNGe expansion ........................................ 1 1. Youth ChalleNGe program .................................................................................................... 1 2. Evidence on the effectiveness of Youth ChalleNGe .............................................................. 2 3. Job ChalleNGe grants ........................................................................................................... 3 B. The Job -

Accountancy, State Board of Administrative Services, Department Of

State of Oregon Telephone Directory - Departmental Listing Accountancy, State Board Of Statewide Audit and Budget Reporting Section 3218 Pringle Road SE Ste 110 Salem, OR 97302-6307 * (SABRS) Fax: (503) 378-3575 155 Cottage St NE U10 Executive Director - Kimberly Fast (503) 378-2280 Fax: (503) 373-7643 Licensing Program Manager - Julie Nadeau (503) 378-2270 Salem, OR 97301-3965 * (503) 378-2277 Investigator - Anthony Truong (503) 378-2273 Manager - Sandy Ridderbusch (503) 373-1863 Investigator - VACANT (503) 378-5041 Senior SABR Auditor - Michele Nichols (503) 378-2227 Licensing Specialist - Ashlie Rios (503) 378-2268 Senior Systems Analyst - Shawn Miller (503) 378-4690 Compliance Specialist - Joel Parks (503) 378-2262 Senior Systems Analyst - John Poitras (503) 378-8203 Front Desk - Leah Von Deylen (503) 378-4181 PICS Auditor - Patrick Sevigny (503) 373-0211 Licensing Specialist - Stacey Janes (503) 378-2264 SABR Auditor - Robert Otero Statewide Accounting and Reporting Section Administrative Services, Department (SARS) of 155 Cottage St NE Fax: (503) 373-7643 155 Cottage Street NE Salem, OR 97301 * Chief Financial Office (CFO) Manager - Robert Hamilton (503) 373-0299 155 Cottage St NE U10 Senior Financial Reporting and Policy (503) 947-8567 Salem, OR 97301-3965 * Analyst - Stacey Chase (503) 373-0724 Fax: (503) 373-7643 Accounting Analyst - Alyssa Engelson (503) 373-0730 Chief Financial Officer - George Naughton (503) 378-5460 Senior Accounting Analyst - Barbara Homewood CFO Executive Assistant - Vacant (503) 378-5087 Statewide Accountant -

BBYCA Youth Application

Battle Born Youth ChalleNGe Academy Lead the Way YOUTH APPLICATION (Part One) The Youth & Medical applications must be submitted in their entirety before consideration can be given for acceptance. Submit your application via mail or email to: Battle Born Youth ChalleNGe Academy PO Box 700 Carlin, NV. 89822 (Use US Postal Service only. UPS/FedEx do not deliver to PO boxes) https://nvng.nv.gov/BBYCA/ Program Coordinator: Lisa Williams [email protected] 775-315-1154 Battle Born Youth ChalleNGe Academy Youth Application Five Step Process for applying to the Battle Born Youth ChalleNGe Academy: PURPOSE: These information pages (1-5) provide you a general overview of the Youth ChalleNGe Program and the Battle Born Youth ChalleNGe Academy (BBYCA). The more you know and understand about the Program, the better you’ll be able to decide if this Program is for you. Keep these pages for your reference. Step One – Attend a program presentation in your area. See website for dates, times, and locations. Youth and guardian attendance at a presentation is mandatory; it affords you the opportunity to learn about the program, expectations, and application process. You will also meet with an Admissions Specialist who will be able to answer your questions and guide you through the application process. Step Two – Application, Part One (Youth): Please complete all the Youth Application Forms (A - L), leaving no questions blank. Submit these along with a copy of: (1) Applicant’s Social Security Card (2) State ID Card, temporary paper copy accepted (3) US birth certificate or INS Proof of Permanent Residency card (I-551) (4) High School Transcript to the Academy address listed below. -

The External Review of Job Corps: an Evidence Scan Report March 2018

The External Review of Job Corps: An Evidence Scan Report March 2018 Jillian Berk Linda Rosenberg Lindsay Cattell Johanna Lacoe Lindsay Fox Myley Dang Elizabeth Brown Submitted to: U.S. Department of Labor Chief Evaluation Office 200 Constitution Ave., NW Washington, DC 20210 Project Officer: Jessica Lohmann Contract Number: DOLQ129633249/DOL-OPS-16-U-00122 Submitted by: Mathematica Policy Research 1100 1st Street, NE 12th Floor Washington, DC 20002-4221 Telephone: (202) 484-9220 Facsimile: (202) 863-1763 Project Director: Jillian Berk Reference Number: 50290.01.440.478.001 DISCLAIMER: THIS REPORT WAS PREPARED FOR THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR (DOL), CHIEF EVALUATION OFFICE, BY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH, UNDER CONTRACT NUMBER DOLQ129633249/DOL-OPS-16-U- 00122. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHORS AND SHOULD NOT BE ATTRIBUTED TO DOL, NOR DOES MENTION OF TRADE NAMES, COMMERCIAL PRODUCTS, OR ORGANIZATIONS IMPLY ENDORSEMENT OF SAME BY THE U.S. GOVERNMENT. JOB CORPS EXTERNAL REVIEW MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank the many people whose cooperation and efforts made the Job Corps External Review possible. In particular, we would like to thank staff at the U.S. Department of Labor who supported this study. Our Project Officer Jessica Lohmann at the Chief Evaluation Office guided this study. Molly Irwin, the Chief Evaluation Officer, was the External Review’s original project officer and provided input throughout the project. The study’s two reports—the Evidence Scan and Future Research reports—benefited from their careful review. We are indebted to staff at the National Office of Job Corps, including Lenita Jacobs-Simmons, Robert Pitulej, Marcus Gray, Erin Fitzgerald, Felicia Charlot, and Edward Benton, who attended in- person meetings, provided helpful comments on draft reports, and participated in interviews. -

Bristol, Matt Dibenedettoeventual Landingwas Spot, Rules- DENNY Hamlingrind-It-Outvs

The Daytona Beach News-Journal’s Godwin Kelly & Ken Willis have covered NASCAR for nearly 60 years combined. godwin.kelly@ NASCAR THIS WEEK news-jrnl.com [email protected] SPEED FREAKS QUESTIONS & ATTITUDE A few questions we had to ask ourselves Compelling questions ... and PHOENIX maybe a few actual answers Your knee-jerk review of Vegas and results of the “new THREE THINGS TO WATCH Is that a look of concern? package”? GODSPEAK: It’s a work in 1. Penske power Let’s call it a mix of mild concern, progress. Drivers have more car balanced by a hesitance to offer control, and there have been It sure looks like Team snap judgment. I tuned into Sun- fewer wrecks. Give it time. Penske has found the day’s race, saw a big pack of cars KEN’S CALL: If it seemed perfect secret key to the new slicing and dicing, and said, “See, at the start, the engineers NASCAR package — two that’s exactly what NASCAR was would eventually mess it up. But wins by two drivers on looking for with the new con- it seems imperfect at the start, consecutive weekends. figurations.” Then I looked in the so maybe the engineers will find Joey Logano credited corner of the screen and realized a way to tighten up the field. Ford’s engineers for solv- it was just the second lap of Reverse psychology, right there. ing the puzzle. “Everyone a green-flag run. By Lap 10, it is going through a learn- The Daytona Beach News-Journal’sbecameGodwinthe Urban Meyer 400 — Kez, then Joey. -

Colleges of Arts & Sciences (85-178)

COLLEGES OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Contents Colleges of Arts & Sciences .......................................... 85 Languages and Literatures of Europe and the Americas ............119 Degrees, Minors and Certificates Offered ..................................86 Linguistics ................................................................................122 General Information ..................................................................87 Second Language Studies ........................................................124 Accreditations and Affiliations....................................................87 English Language Institute....................................................126 Scholarships and Awards ...........................................................87 Hawaii English Language Program........................................127 A&S Honor Societies ..................................................................87 College of Natural Sciences .............................................128 Student Organizations ...............................................................87 Administration .........................................................................127 Undergraduate Programs ...........................................................87 College Certificate ...................................................................128 Requirements for Undergraduate Degrees from the Colleges of Arts Mathematical Biology Undergraduate Certificate ..................128 and Sciences ..............................................................................87 -

National Guard Youth Challenge: Program Progress in 2016-2017

National Guard Youth ChalleNGe Program Progress in 2016 –2017 Jennie W. Wenger, Louay Constant, Linda Cottrell C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2276 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0007-9 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover Image by Staff Sgt. Darron Salzer, National Guard Bureau Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The National Guard Youth ChalleNGe program is a residential, quasi-military program for youth ages 16 to 18 who are experiencing difficulty in traditional high school. -

Ed 242 05 Ea 016 574

DOCUMENT RESUME '' ED 242 05 EA 016 574., AUTHOR Raywid, Matey Anne TITLE directory: Public Secondary Alternative Schools in the United States and Several Canapan Provinces. INSTITUTION Hofstra Univ.,11iempstead, NYProject on Alternatives in Education. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. of Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 82 GRANT NIE-G-80-0194 NOTE X74p.; For related document, see EA 016 575.' AVAILABLE FROM"Publication's, Prdject on Alternatives in Education, .Hofstra 'University, Ilempstead,NT 11550 ($7.00; make checks payable'to Mary Anne Raywid, PAE). PUB TYPE Reference Materials'- DireCtories/Catalogs (132?- .,-- 'EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. - DESCRIPTORS Adolescents; *EXperimental Schools; *Nontraditional Education; *Public Schools; Sdhool Choie; *Secondary Education' IDENTIFIERS *Project on Alternatives in Education ABSTRACT This,directorypresents the names and addressei of' 2,500 public alternative schools and programs serving secondary school-age children in the United States and three Canadian provinces (Ontario, Britiih.Columbia, and,Alberta).'The.addresses are listed alphabetically by state, with the-Canadian entries in a separate section at the end. Each school or program listed has been assigned a .1 six-digit number; the first two digits indicate the state (numbered in alphaiSetical order),the,nexi three designate the school in the, order it was located, and the final digit indicates the school type, where discernible: 0 = unsPecified, I = senior high, 2 = junior high, 3 = middle school, 4 = continuation ,school, 5 =,speciarpoptlIation school (special populations may be pregnant teenagers, specTal education students, and students in punitive programs), 6 = combined junior- senior high,. 7 = elementary through senior high, 8 = elementary through junior higir. The list will be updated. -

Department of Military and Veterans' Affairs

FISCAL YEAR 2021-2022 ANALYSIS OF THE NEW JERSEY BUDGET DEPARTMENT OF MILITARY AND VETERANS’ AFFAIRS Prepared by the NNewew JerseyJersey LLegislatureegislature OOfficeffice ooff LLEGISLATIVEEGISLATIVE SERVICESSERVICES April 2021 NNEWEW JJERSEYERSEY SSTATETATE LLEGISLATUREEGISLATURE SENATE BUDGET AND APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE Paul A. Sarlo (D), 36th District (Parts of Bergen and Passaic), Chair Sandra B. Cunningham (D), 31st District (Part of Hudson), Vice-Chair Dawn Marie Addiego (D), 8th District (Parts of Atlantic, Burlington and Camden) Nilsa Cruz-Perez (D), 5th District (Parts of Camden and Gloucester) Patrick J. Diegnan, Jr. (D), 18th District (Part of Middlesex) Linda R. Greenstein (D), 14th District (Parts of Mercer and Middlesex) Declan J. O’Scanlon, Jr. (R), 13th District (Part of Monmouth) Steven V. Oroho (R), 24th District (All of Sussex, and parts of Morris and Warren) M. Teresa Ruiz (D), 29th District (Part of Essex) Troy Singleton (D), 7th District (Part of Burlington) Michael L. Testa, Jr. (R), 1st District (All of Cape May, parts of Atlantic and Cumberland) Samuel D. Thompson (R), 12th District (Parts of Burlington, Middlesex, Monmouth and Ocean) GENERAL ASSEMBLY BUDGET COMMITTEE Eliana Pintor Marin (D), 29th District (Part of Essex), Chair John J. Burzichelli (D), 3rd District (All of Salem, parts of Cumberland and Gloucester), Vice-Chair Daniel R. Benson (D), 14th District (Parts of Mercer and Middlesex) Robert D. Clifton (R), 12th District (Parts of Burlington, Middlesex, Monmouth and Ocean) Serena DiMaso (R), 13th District (Part of Monmouth) Gordon M. Johnson (D), 37th District (Part of Bergen) John F. McKeon (D), 27th District (Parts of Essex and Morris) Nancy F. -

Congressional Record—House H6797

July 25, 2000 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE H6797 In 1976, the U.S. became a signatory to the after spending years on death row for crimes I hope that the authors of today's bill are International Covenant on Civil and Polit- they did not commit. truly serious about the need to prevent the ical Rights (CCPR), which 143 other nations It is cases like these that convinced such or- execution of the innocent, and that they will have also joined. Article 6(5) states, ``Sen- ganizations as the American Bar Associa- tence of death shall not be imposed for join the 79 members of this HouseÐboth Re- crimes committed by persons below eighteen tionÐwhich has no position on the death pen- publicans and DemocratsÐwho have cospon- years of age and shall not be carried out on alty per seÐto call for a halt to executions sored the Innocence Protection Act. pregnant women.'' The U.S. entered a partial until each jurisdiction can ensure that it has Madam Speaker, I have no further re- reservation to Article 6(5), which reads, ``The taken steps to minimize the risk that innocent quests for time, and I yield back the United States reserves the right, subject to persons may be executed. balance of my time. its Constitutional constraints, to impose It is cases like these that convinced Gov- The SPEAKER pro tempore (Mrs. capital punishment on any person (other ernor RyanÐa Republican and a supporter of EMERSON). The question is on the mo- than a pregnant woman) duly convicted the death penaltyÐto put a stop to executions tion offered by the gentleman from Ar- under existing or future laws permitting the kansas (Mr.