Eriogonums Or Wild Buckwheats, an Exploration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Vegetation Map in Support of the DRECP

CALIFORNIA VEGETATION MAP IN SUPPORT OF THE DESERT RENEWABLE ENERGY CONSERVATION PLAN (2014-2016 ADDITIONS) John Menke, Edward Reyes, Anne Hepburn, Deborah Johnson, and Janet Reyes Aerial Information Systems, Inc. Prepared for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife Renewable Energy Program and the California Energy Commission Final Report May 2016 Prepared by: Primary Authors John Menke Edward Reyes Anne Hepburn Deborah Johnson Janet Reyes Report Graphics Ben Johnson Cover Page Photo Credits: Joshua Tree: John Fulton Blue Palo Verde: Ed Reyes Mojave Yucca: John Fulton Kingston Range, Pinyon: Arin Glass Aerial Information Systems, Inc. 112 First Street Redlands, CA 92373 (909) 793-9493 [email protected] in collaboration with California Department of Fish and Wildlife Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program 1807 13th Street, Suite 202 Sacramento, CA 95811 and California Native Plant Society 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento, CA 95816 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this project was provided by: California Energy Commission US Bureau of Land Management California Wildlife Conservation Board California Department of Fish and Wildlife Personnel involved in developing the methodology and implementing this project included: Aerial Information Systems: Lisa Cotterman, Mark Fox, John Fulton, Arin Glass, Anne Hepburn, Ben Johnson, Debbie Johnson, John Menke, Lisa Morse, Mike Nelson, Ed Reyes, Janet Reyes, Patrick Yiu California Department of Fish and Wildlife: Diana Hickson, Todd Keeler‐Wolf, Anne Klein, Aicha Ougzin, Rosalie Yacoub California -

Appendix F3 Rare Plant Survey Report

Appendix F3 Rare Plant Survey Report Draft CADIZ VALLEY WATER CONSERVATION, RECOVERY, AND STORAGE PROJECT Rare Plant Survey Report Prepared for May 2011 Santa Margarita Water District Draft CADIZ VALLEY WATER CONSERVATION, RECOVERY, AND STORAGE PROJECT Rare Plant Survey Report Prepared for May 2011 Santa Margarita Water District 626 Wilshire Boulevard Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90017 213.599.4300 www.esassoc.com Oakland Olympia Petaluma Portland Sacramento San Diego San Francisco Seattle Tampa Woodland Hills D210324 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cadiz Valley Water Conservation, Recovery, and Storage Project: Rare Plant Survey Report Page Summary ............................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................2 Objective .......................................................................................................................... 2 Project Location and Description .....................................................................................2 Setting ................................................................................................................................... 5 Climate ............................................................................................................................. 5 Topography and Soils ......................................................................................................5 -

An Overview of Buckwheat (Fagopyrum Spp)-An Underutilized

Available online at www.ijmrhs.com al R edic ese M a of rc l h a & n r H u e o a J l l t h International Journal of Medical Research & a n S ISSN No: 2319-5886 o c i t i Health Sciences, 2020, 9(7): 39-44 e a n n c r e e t s n I • • I J M R H S An Overview of Buckwheat (Fagopyrum spp)-An Underutilized Crop in India-Nutritional Value and Health Benefits Aneesha Nalinkumar* and Pratibha Singh Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies, Haryana, India *Corresponding e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Buckwheat is one of the pseudocereals grown annually in hilly regions of India. It belongs to the family Polygonaceae and genus (Fagopyrum spp.) Buckwheat is adaptable to extreme cold temperatures, stress conditions of water, less soil fertility and varying climatic conditions, making it a sustainable crop. A literature search on Buckwheat was done using PubMed and Google search engines and reviewed to prepare an overview of its cultivation, nutritional and health value. In India, twenty species of Buckwheat are cultivated across various hilly regions. Out of these only nine species have desirable nutritional value and two are commonly grown. They are Fagopyrum esculentum Moench (Common buckwheat) and Fagopyrum tataricum (Tartary buckwheat). However, the cultivation of Buckwheat has declined in the 20th century making it an underutilized crop. Buckwheat has good amount of nutrients and many health benefits. There is a need to research about this under-utilized crop and create awareness as this crop has many nutritional and health benefits. -

Spatial Distribution of Coast and Dune Buckwheat (Eriogonum Latifolium & E

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2004 Spatial distribution of coast and dune buckwheat (Eriogonum latifolium & E. parvifolium) in a restoration site on the Fort Ord dunes of California Heather Wallingford California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Wallingford, Heather, "Spatial distribution of coast and dune buckwheat (Eriogonum latifolium & E. parvifolium) in a restoration site on the Fort Ord dunes of California" (2004). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 60. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/60 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spring 2004 Capstone Heather Wallingford Spatial Distribution of Coast and Dune Buckwheat (Eriogonum latifolium & E. parvifolium) in a Restoration Site on the Fort Ord Dunes of California A Capstone Project Presented to the Faculty of Earth Systems Science and Policy in the College of Science, Media Arts, and Technology at California State University, Monterey Bay in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Heather Wallingford May 5, 2004 1 Spring 2004 Capstone Heather Wallingford Abstract Coast and dune buckwheat (Eriogonum parvifolium & E. latifolium) are native plants to the Fort Ord sand dunes which are essential for the survivorship of the federally- endangered Smith’s blue butterfly (Euphilotes enoptes smithi). -

Draft Plant Propagation Protocol

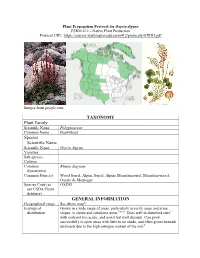

Plant Propagation Protocol for Oxyria digyna ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Protocol URL: https://courses.washington.edu/esrm412/protocols/OXDI3.pdf Images from google.com TAXONOMY Plant Family Scientific Name Polygonaceae Common Name Buckwheat Species Scientific Name Scientific Name Oxyria digyna Varieties Sub-species Cultivar Common Rheum digynum Synonym(s) Common Name(s) Wood Sorrel, Alpine Sorrel, Alpine Mountainsorrel, Mountain-sorrel, Oxyrie de Montagne Species Code (as OXDI3 per USDA Plants database) GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range See above map12 Ecological Grows in a wide range of areas, particularly in rocky areas and scree distribution slopes, in alpine and subalpine areas.5,6,10 Does well in disturbed sites11 with soils not too acidic, and moist but well drained. Can grow successfully in open areas with little to no shade, and often grows beneath bird nests due to the high nitrogen content of the soil.4 Climate and elevation range Local habitat and Subalpine forest or wetland riparian species2 abundance Plant strategy type / Produces small, wind dispersed seeds, making it a weed-like pioneer successional stage species, especially in disturbed sites.3 Tolerant of sun stress, but not of interspecies competition, particularly that of Ranunculus glacialis. Is able to germinate after being buried beneath snow.8 Has an intermediate tolerance for shade, a low tolerance for drought and anoxic conditions, and is adapted to coarse to medium soils. Seedlings spread slowly and are moderately vigorous, and the plant does not usually propagate vegetatively.12 Plant characteristics Oxyria digyna is a perennial herb which grows to approx. 2ft tall and 1ft wide.4 It is hairless, having a branching crown and several stems11 with swollen nodes8, and it is reddish tinged11. -

IP Athos Renewable Energy Project, Plan of Development, Appendix D.2

APPENDIX D.2 Plant Survey Memorandum Athos Memo Report To: Aspen Environmental Group From: Lehong Chow, Ironwood Consulting, Inc. Date: April 3, 2019 Re: Athos Supplemental Spring 2019 Botanical Surveys This memo report presents the methods and results for supplemental botanical surveys conducted for the Athos Solar Energy Project in March 2019 and supplements the Biological Resources Technical Report (BRTR; Ironwood 2019) which reported on field surveys conducted in 2018. BACKGROUND Botanical surveys were previously conducted in the spring and fall of 2018 for the entirety of the project site for the Athos Solar Energy Project (Athos). However, due to insufficient rain, many plant species did not germinate for proper identification during 2018 spring surveys. Fall surveys in 2018 were conducted only on a reconnaissance-level due to low levels of rain. Regional winter rainfall from the two nearest weather stations showed rainfall averaging at 0.1 inches during botanical surveys conducted in 2018 (Ironwood, 2019). In addition, gen-tie alignments have changed slightly and alternatives, access roads and spur roads have been added. PURPOSE The purpose of this survey was to survey all new additions and re-survey areas of interest including public lands (limited to portions of the gen-tie segments), parcels supporting native vegetation and habitat, and windblown sandy areas where sensitive plant species may occur. The private land parcels in current or former agricultural use were not surveyed (parcel groups A, B, C, E, and part of G). METHODS Survey Areas: The area surveyed for biological resources included the entirety of gen-tie routes (including alternates), spur roads, access roads on public land, parcels supporting native vegetation (parcel groups D and F), and areas covered by windblown sand where sensitive species may occur (portion of parcel group G). -

TAXONOMY Plant Family Species Scientific Name GENERAL

Plant Propagation Protocol for Eriogonum niveum ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Protocol URL: https://courses.washington.edu/esrm412/protocols/ERNI2.pdf Spring 2014 North America Distribution Washington State Distribution Source: USDA PLANTS Database TAXONOMY Plant Family Scientific Name Polygonaceae Common Name Buckwheat Family Species Scientific Name Scientific Name Eriogonum niveum Douglas ex Benth. Varieties Eriogonum niveum Douglas ex. Benth. var. dichotomum (Douglas ex Benth.) M.E. Jones Eriogonum niveum Douglas ex. Benth. var. decumbens (Benth.) Torr. & A. Gray Sub-species Eriogonum niveum Douglas ex. Benth. ssp. decumbens (Benth.) S. Stokes Cultivar Common Synonym(s) Eriogonum strictum Benth. var. lachnostegium Common Name(s) Snow buckwheat, canyon heather 6 Species Code (as per USDA Plants ERNI2 database) GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range Found mainly on the grassy plains east of the Cascade Range in southern British Columbia, west-central Idaho, northeastern Oregon, and eastern Washington.1 See maps above for distribution in North America and Washington state. Ecological distribution Found in sand to gravelly flats, slopes, bluffs, and rocky, often volcanic outcrops, mixed grassland and sagebrush communities and conifer woodlands.1 Climate and elevation range Elevation: 150-1500 m 2 Cold Hardiness Zone: 5a-7a 6 Mean Annual Precipitation: 150 – 460 mm 2 Soil: Well-drained sands to clay 2 Local habitat and abundance Common in big sage (Artemissia tridentate), antelope bitterbrush (Purshia tridentate), and open Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) areas. It also occurs in the canyon grasslands of the Snake and Columbia River systems.2 Found primarily in full sun but will grow in partial shade such as open Ponderosa pine hillsides.6 Tolerates extremely droughty soils and is a common occupant of dry, rocky southern exposures.6 Plant strategy type / successional Colonizer 2 stage Very successful pioneer species6 Plant characteristics Rarity: Locally Common 3 Dense perennial subshrub with erect leaves. -

Fagopyrum Esculentum Ssp. Ancestrale-A Hybrid Species Between Diploid F

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 16 July 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01073 Fagopyrum esculentum ssp. ancestrale-A Hybrid Species Between Diploid F. cymosum and F. esculentum Cheng Cheng 1,2,YuFan 1,YuTang 3, Kaixuan Zhang 1, Dinesh C. Joshi 4, Rintu Jha 1, Dagmar Janovská 5, Vladimir Meglicˇ 6, Mingli Yan 2* and Meiliang Zhou 1* 1 Institute of Crop Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2 School of Life Sciences, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan, China, 3 Department of Tourism, Sichuan Tourism University, Chengdu, China, 4 Indian Council of Agricultural Research- Vivekananda Institute of Hill Agriculture, Almora, India, 5 Gene Bank, Crop Research Institute, Prague, Czechia, 6 Crop Science Department, Agricultural Institute of Slovenia, Ljubljana, Slovenia Fagopyrum cymosum is considered as most probable wild ancestor of cultivated buckwheat. However, the evolutionary route from F. cymosum to F. esculentum Edited by: remains to be deciphered. We hypothesized that a hybrid species exists in natural Natascha D. Wagner, University of Göttingen, Germany habitats between diploid F. cymosum and F. esculentum. The aim of this research was Reviewed by: to determine the phylogenetic position of F. esculentum ssp. ancestrale and to provide Angela Jean McDonnell, new thoughts on buckwheat evolution. Different methodologies including evaluation of Chicago Botanic Garden, morphological traits, determination of secondary metabolites, fluorescence in situ United States Kyong-Sook Chung, hybridization (FISH), comparative chloroplast genomics, and molecular markers were Jungwon University, South Korea deployed to determine the phylogenetic relationship of F. esculentum ssp. ancestrale with *Correspondence: F. cymosum and F. esculentum. The ambiguity observed in morphological pattern of Mingli Yan [email protected] genetic variation in three species revealed that F. -

Alpine Flora

ALPINE FLORA -- PLACER GULCH Scientific and common names mostly conform to those given by John Kartesz at bonap.net/TDC FERNS & FERN ALLIES CYSTOPTERIDACEAE -- Bladder Fern Family Cystopteris fragilis Brittle Bladder Fern delicate feathery fronds hiding next to rocks and cliffs PTERIDACEAE -- Maidenhair Fern Family Cryptogramma acrostichoides American Rockbrake two different types of fronds; talus & rocky areas GYMNOSPERMS PINACEAE -- Pine Family Picea englemannii Englemann's Spruce ANGIOSPERMS -- MONOCOTS CYPERACEAE -- Sedge Family Carex haydeniana Hayden's Sedge very common alpine sedge; compact, dark, almost triangular inflorescence Eriophorum chamissonis Chamisso's Cotton-Grass Cottony head; no leaves on culm ALLIACEAE -- Onion Family Allium geyeri Geyer's Onion pinkish; onion smell LILIACEAE -- Lily Family Llyodia serotina Alp Lily white; small plant in alpine turf MELANTHIACEAE -- False Hellebore Family Anticlea elegans False Deathcamas greenish white; showy raceme above basal grass-like leaves Veratrum californicum Cornhusk Lily; CA False Hellebore greenish; huge lvs; huge plant; mostly subalpine ORCHIDACEAE -- Orchid Family Plantanthera aquilonis Green Bog Orchid greenish, in bracteate spike, spur about as long as or a bit shorter than lip POACEAE -- Grass Family Deschampsia caespitosa Tufted Hair Grass open inflorescence; thin, wiry leaves; 2 florets/spikelet; glumes longer than low floret Festuca brachyphylla ssp. coloradoensis Short-leaf Fescue dark; narrow inflorescence; thin, wiry leaves Phleum alpinum Mountain Timothy dark; -

El Segundo Blue Butterfly and Dune Buckwheat

K E E R S Marina C A del Rey N a O L L A n B t El Segundo Blue Butterfly a M H o I n and the Dune Buckwheat S i LAX c T The El Segundo blue butterfly (Euphilotes battoides allyni) a Playa O del Rey depends on the dune buckwheat (Eriogonum parvifolium) B R for its entire life cycle. Adult a I y butterflies feed on the dune El Segundo C buckwheat’s nectar and lay eggs on the flowerheads. The S A caterpillars eat the flowerheads, Manhattan N form pupae in the soil, and then Dune buckwheat (Eriogonum parvifolium) Beach D they wait for the next summer to emerge as butterflies. An individual butterfly Hermosa can spend its entire life within a few yards of a single plant. D Beach El Segundo blue butterfly (Euphilotes battoides allyni); photo by Jess Morton Urban development reduced the local distribution of dune buckwheat to three U Adult King N Butterfly isolated areas: the dunes west of LAX, Chevron’s El Segundo refinery property, Beach Bluffs Egg Harbor and the bluffs northwest of Palos Restoration Project E Verdes Estates. A dramatic decline in S he Beach Bluffs Restoration Project Larva the El Segundo blue butterfly Tbegan in 2001 when a group of local Redondo residents, nonprofit groups, and population following the loss of government agencies united to implement Beach a common vision of restoring the native vegetation of the bluffs along the southern suitable habitat led to its listing as a portion of Santa Monica Bay, between Pupa Ballona Creek and the Palos Verdes Spends winter federally endangered species. -

Polygonaceae of Alberta

AN ILLUSTRATED KEY TO THE POLYGONACEAE OF ALBERTA Compiled and writen by Lorna Allen & Linda Kershaw April 2019 © Linda J. Kershaw & Lorna Allen This key was compiled using informaton primarily from Moss (1983), Douglas et. al. (1999) and the Flora North America Associaton (2005). Taxonomy follows VAS- CAN (Brouillet, 2015). The main references are listed at the end of the key. Please let us know if there are ways in which the kay can be improved. The 2015 S-ranks of rare species (S1; S1S2; S2; S2S3; SU, according to ACIMS, 2015) are noted in superscript (S1;S2;SU) afer the species names. For more details go to the ACIMS web site. Similarly, exotc species are followed by a superscript X, XX if noxious and XXX if prohibited noxious (X; XX; XXX) according to the Alberta Weed Control Act (2016). POLYGONACEAE Buckwheat Family 1a Key to Genera 01a Dwarf annual plants 1-4(10) cm tall; leaves paired or nearly so; tepals 3(4); stamens (1)3(5) .............Koenigia islandica S2 01b Plants not as above; tepals 4-5; stamens 3-8 ..................................02 02a Plants large, exotic, perennial herbs spreading by creeping rootstocks; fowering stems erect, hollow, 0.5-2(3) m tall; fowers with both ♂ and ♀ parts ............................03 02b Plants smaller, native or exotic, perennial or annual herbs, with or without creeping rootstocks; fowering stems usually <1 m tall; fowers either ♂ or ♀ (unisexual) or with both ♂ and ♀ parts .......................04 3a 03a Flowering stems forming dense colonies and with distinct joints (like bamboo -

Apomixis Is Not Prevalent in Subnival to Nival Plants of the European Alps

Annals of Botany 108: 381–390, 2011 doi:10.1093/aob/mcr142, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org Apomixis is not prevalent in subnival to nival plants of the European Alps Elvira Ho¨randl1,*, Christoph Dobesˇ2, Jan Suda3,4, Petr Vı´t3,4, Toma´sˇ Urfus3,4, Eva M. Temsch1, Anne-Caroline Cosendai1, Johanna Wagner5 and Ursula Ladinig5 1Department of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna, A-1030 Vienna, Austria, 2Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna, A-1090 Vienna, Austria, 3Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, CZ-128 01 Prague, Czech Republic, 4Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, CZ-252 43 Pru˚honice, Czech Republic and 5Institute of Botany, University of Innsbruck, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria * For correspondence. E-mail [email protected] Received: 2 December 2010 Returned for revision: 14 January 2011 Accepted: 28 April 2011 Published electronically: 1 July 2011 † Background and Aims High alpine environments are characterized by short growing seasons, stochastic climatic conditions and fluctuating pollinator visits. These conditions are rather unfavourable for sexual reproduction of flowering plants. Apomixis, asexual reproduction via seed, provides reproductive assurance without the need of pollinators and potentially accelerates seed development. Therefore, apomixis is expected to provide selective advantages in high-alpine biota. Indeed, apomictic species occur frequently in the subalpine to alpine grassland zone of the European Alps, but the mode of reproduction of the subnival to nival flora was largely unknown. † Methods The mode of reproduction in 14 species belonging to seven families was investigated via flow cyto- metric seed screen.