Composing, Remembering, and Performing Identity at Charles Towne Landing, 1966 Through 1971: Rhetorical Identification As Defensive and Antagonistic Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Take a Lesson from Butch. (The Pros Do.)

When we were children, we would climb in our green and golden castle until the sky said stop. Our.dreams filled the summer air to overflowing, and the future was a far-off land a million promises away. Today, the dreams of our own children must be cherished as never before. ) For if we believe in them, they will come to believe in I themselves. And out of their dreams, they will finish the castle we once began - this time for keeps. Then the dreamer will become the doer. And the child, the father of the man. NIETROMONT NIATERIALS Greenville Division Box 2486 Greenville, S.C. 29602 803/269-4664 Spartanburg Division Box 1292 Spartanburg, S.C. 29301 803/ 585-4241 Charlotte Division Box 16262 Charlotte, N.C. 28216 704/ 597-8255 II II II South Caroli na is on the move. And C&S Bank is on the move too-setting the pace for South Carolina's growth, expansion, development and progress by providing the best banking services to industry, business and to the people. We 're here to fulfill the needs of ou r customers and to serve the community. We're making it happen in South Carolina. the action banlt The Citizens and Southern National Bank of South Carolina Member F.D.I.C. In the winter of 1775, Major General William Moultrie built a fort of palmetto logs on an island in Charleston Harbor. Despite heavy opposition from his fellow officers. Moultrie garrisoned the postand prepared for a possible attack. And, in June of 1776, the first major British deftl(lt of the American Revolution occurred at the fort on Sullivan's Island. -

Phylogeography of a Tertiary Relict Plant, Meconopsis Cambrica (Papaveraceae), Implies the Existence of Northern Refugia for a Temperate Herb

Article (refereed) - postprint Valtueña, Francisco J.; Preston, Chris D.; Kadereit, Joachim W. 2012 Phylogeography of a Tertiary relict plant, Meconopsis cambrica (Papaveraceae), implies the existence of northern refugia for a temperate herb. Molecular Ecology, 21 (6). 1423-1437. 10.1111/j.1365- 294X.2012.05473.x Copyright © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. This version available http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/17105/ NERC has developed NORA to enable users to access research outputs wholly or partially funded by NERC. Copyright and other rights for material on this site are retained by the rights owners. Users should read the terms and conditions of use of this material at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/policies.html#access This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this and the publisher’s version remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from this article. The definitive version is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com Contact CEH NORA team at [email protected] The NERC and CEH trademarks and logos (‘the Trademarks’) are registered trademarks of NERC in the UK and other countries, and may not be used without the prior written consent of the Trademark owner. 1 Phylogeography of a Tertiary relict plant, Meconopsis cambrica 2 (Papaveraceae), implies the existence of northern refugia for a 3 temperate herb 4 Francisco J. Valtueña*†, Chris D. Preston‡ and Joachim W. Kadereit† 5 *Área de Botánica, Facultad deCiencias, Universidad de Extremadura, Avda. de Elvas, s.n. -

South Carolina SOUTH CAROLINA

South Carolina `I.H.T. Ports and Harbors: 7 SOUTH CAROLINA, USA Airports: 6 SLOGAN: PALMETTO STATE ABBREVIATION: SC HOTELS / MOTELS / INNS AIKEN SOUTH CAROLINA COMFORT SUITES 3608 Richland Ave. W. - 29801 AIKEN SOUTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (803) 641-1100, www.comfortsuites.com AIKEN SOUTH CAROLINA EXECUTIVE INN 3560 Richland Ave W Aiken UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 803-649-3968 803-649-3968 ANDERSON SOUTH CAROLINA COMFORT SUITES 118 Interstate Blvd. - 29621 ANDERSON SOUTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (864) 375-0037, www.comfortsuites.com KNIGHTS'INN 2688 Gateway Drive Anderson UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 530-365-2753 530-365-6083 QUALITY INN 3509 Clemson Blvd. - 29621 ANDERSON SOUTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (864) 226-1000 BEAUFORT SOUTH CAROLINA COMFORT INN 2625 W. Boundary St. (US 21) - 29902 BEAUFORT SOUTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (843) 525-9366, www.comfortinn.com BEAUFORT SOUTH SLEEP INN 2625 Boundary Street PO Box 2146-29902 BEAUFORT SOUTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA State Dialling Code (Tel/Fax): ++1 803 CHARLESTON SOUTH CAROLINA South Carolina Tourism Sales Office: 1205 Pendleton Street, Suite 112, ANCHORAGE INN, 26 Vendue Range Street, Charleston, SC 29401, United Columbia, SC 29201 Tel: 734 0128 Fax: 734 1163 E-mail: [email protected] States, (843) 723-8300, www.anchoragencharleston.com Website: www.discoversouthcarolina.com ANDREW PINCKNEY INN, 40 Pinckney Street, Charleston, SC 29401, United Capital: Columbia Time: GMT – 5 States, (843) 937-8800, www.andrewpinckneyinn.com Background: South Carolina entered the Union on May 23, 1788, as the eighth of BEST WESTERN KING CHARLES INN, 237 Meeting Street, Charleston, SC the original 13 states. -

Archeology at the Charles Towne Site

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Research Manuscript Series Institute of 5-1971 Archeology at the Charles Towne Site (38CH1) on Albemarle Point in South Carolina, Part I, The exT t Stanley South University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/archanth_books Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation South, Stanley, "Archeology at the Charles Towne Site (38CH1) on Albemarle Point in South Carolina, Part I, The exT t" (1971). Research Manuscript Series. 204. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/archanth_books/204 This Book is brought to you by the Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Institute of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Manuscript Series by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archeology at the Charles Towne Site (38CH1) on Albemarle Point in South Carolina, Part I, The exT t Keywords Excavations, South Carolina Tricentennial Commission, Colonial settlements, Ashley River, Albemarle Point, Charles Towne, Charleston, South Carolina, Archeology Disciplines Anthropology Publisher The outhS Carolina Institute of Archeology and Anthropology--University of South Carolina Comments In USC online Library catalog at: http://www.sc.edu/library/ This volume constitutes Part I, the text of the report on the archeology done at the Charles Towne Site in Charleston County, South Carolina. A companion -

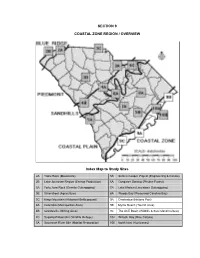

Coastal Zone Region / Overview

SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & Canals) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Production) 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battleground) 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island Culture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restoration) 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW - Index Map to Coastal Zone Overview Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 9 - Power Thinking Activity - "Turtle Trot" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 9-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Coastal Zone p. 9-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 9-3 . - Carolina Grand Strand p. 9-3 . - Santee Delta p. 9-4 . - Sea Islands - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 9-5 . - Coastal Zone Attracts Settlers p. 9-5 . - Native American Coastal Cultures p. 9-5 . - Early Spanish Settlements p. 9-5 . - Establishment of Santa Elena p. 9-6 . - Charles Towne: First British Settlement p. 9-6 . - Eliza Lucas Pinckney Introduces Indigo p. 9-7 . - figure 9-1 - "Map of Colonial Agriculture" p. 9-8 . - Pirates: A Coastal Zone Legacy p. 9-9 . - Charleston Under Siege During the Civil War p. 9-9 . - The Battle of Port Royal Sound p. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

Appendix E Community Characterization Report

LC Appendix E Community Characterization Report RT This page intentionally left blank. Community Characterization Report Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Project Description ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Community Characterization .......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Environmental Justice .................................................................................................... 7 1.4 Limited English Proficiency ............................................................................................. 8 2 Regional Context ................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 History ............................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Local Plans and Initiatives ............................................................................................ 12 2.3 Transportation .............................................................................................................. 20 2.4 Economic Outlook and Employment ............................................................................ 22 2.5 Socioeconomic Characteristics .................................................................................... 24 -

2020 Charleston Area Road Races, Trail Runs

Last Updated: 10/27/20 2020 CHARLESTON AREA ROAD RACES, TRAIL RUNS, ENDURANCE, MULTI-SPORT 2020 Start 2020 End Sports Type Sports Event Event Organizer(s) Venue(s) Municipality / Area Web site 1/1/20 1/1/20 Road Race Race the Landing New Year Pajama Run 5K/10K TimingInc.com Charles Towne Landing Charleston New Year Day Pajama Run 1/4/20 1/4/20 Road Race Bulldog Breakaway New Year's 5K The Citadel The Citadel Charleston Bulldog Breakaway New Years 5K 1/11/20 1/11/20 Marathon Charleston Marathon, 1/2 and 5K (10th) Capstone Event Group Charleston Charleston Charleston Marathon 1/18/20 1/18/20 Duathlon Off-Road Duathlon Run (2m+2m) and Bike (7m) (3rd) CCPRC Laurel Hill County Park Mt. Pleasant Off-Road Duathlon 1/18/20 1/18/20 Road Race Frozen: H3 100K, 60K, and 16.3 miles Trail Run Jerico Horse Trails- Bethera - Berkeley CountyFrozen: H3 1/25/20 1/25/20 Road Race Charlie Post Classic 15K/5K (37th) CRC Sullivan's Island Sullivan's Island Charlie Post Classic 15K/5K 1/25/20 1/25/20 Fun Run The Great Amazing Race 1.5m West Ashley Park Charleston The Great Amazing Race 2/1/20 2/1/20 Road Race Hallucination 24 Hr Trail Run (6HR/12H/24HR) Middleton Place Charleston Hallucination 6/12/24 Hour Trail Run 2/1/20 2/1/20 1/2 Marathon Save the Light 1/2M and 5K CCPRC Folly Beach Pier Folly Beach Save The Lighthouse 13.1 & 5K 2/8/20 2/8/20 Road Race Cupids Chase 5K Summerville Summerville Cupid's Chase 5K 2/8/20 2/8/20 Road Race Mardi Gras 5K and Fun Run Blessed Sacred Catholic Church James Island County Park James Island Mardi Gras 5K and Fun Run 2/12/20 -

Holden Car Show

22,000 copies / month Community News, Local Businesses, Local Events and Free TV Guide 4TH AUGUST - 20TH AUGUST 2017 VOL 34 - ISSUE 16 Sandstone MARK VINT Sales Holden Car Show 9651 2182 Buy Direct From the Quarry 5th & 6th of August 2017 270 New Line Road Dural NSW 2158 9652 1783 Hawkesbury Showground, [email protected] Handsplit ABN: 84 451 806 754 Random Flagging $55m2 Clarendon NSW WWW.DURALAUTO.COM 113 Smallwood Rd Glenorie Details on page 2 Community News Holden Car Show Hawkesbury Showground, Clarendon on the first Sunday in August annually, is Home to Australia’s Largest Display of Holdens. There will be lots of activities for the whole family throughout the day. Including swap meet, trade stands, food stands, drinks, ice creams, and featuring those fantastic Holdens. The NSW All Holden Day is supported by dozens of NSW Holden Clubs which cater for all Holden enthusiasts and every Holden ever produced. The NSW All Holden Day entry is open to all Holden Badged Vehicles (when new). The 32nd NSW All Holden Day will be held on the 5th & 6th of August 2017. There is a 2 day swap meet held on both Saturday and Sunday from 6am. The Display Day for Original and customised Holdens will be proudly displayed from first to current models on the Sunday from 9am. So enter your Holden sedan, ute, wagon, van, 1 tonner, be it stock or modified it doesn’t matter, enter now and be part of this great day. This year we celebrate 32 years of the NSW All Holden Day! Spectator Admission: $5 Adults. -

State Parks Garden Booklet

Rose Hill Plantation State Historic Site Heirloom Kitchen Garden Historic Gardens The Heirloom Kitchen Garden at Rose Hill Planta- tion represents the original gardens which would have supplied the table of South Carolina’s Governor of in SC State Parks Secession William H. Gist. The Rose Hill Heirloom Kitchen Garden includes Kitchen Gardens, Fruit Orchards and Vineyards heirloom varieties like Chioggia Beets, Purple Wonder Eggplant, Speckled Glory Butterbeans, Annie Wills Watermelon, Redleaf Cotton, Indigo, Old Henry Sweet Potato, as well as varieties of sweet onions, red cab- bage, potatoes, tomatoes, peanuts, pumpkins, okra, corn and pole beans. Herbs in- clude savory, chives, sweet basil, feverfew, horehound, tansy, dill, catmint and sweet parsley. The site also contains several ornamental rose gardens. Garden related programs include Heirloom Gardening: Spring Vegetables and Roses and The Fall Garden: Heirloom Vegetables and Roses . The garden is open during normal park operating hours for self-guided tours. Andrew Jackson State Park Charles Towne Landing 196 Andrew Jackson Park Rd. State Historic Site Lancaster, SC 29720 1500 Old Towne Rd. (803) 285-3344 Charleston, SC 29407 Open Hours: 8am - 6pm (winter), (843) 852-4200 9am - 9pm (summer) Open Hours: Daily 9am - 5pm Office Hours: 11am—Noon Office Hours: Daily 9am - 5pm Kings Mountain State Park Redcliffe Plantation 1277 Park Rd. State Historic Site Blacksburg, SC 29702 181 Redcliffe Rd (803) 222-3209 Beech Island, SC 29842 Open Hours: 8am - 6pm (winter), (803) 827-1473 7am - 9pm (summer) Open Hours: Thurs-Mon 9am-6pm Office Hours: 11am - Noon, 4 pm - (5pm in winter) 5pm Mon-Fri Office Hours: 11am—Noon Rose Hill Plantation State Historic Site 2677 Sardis Rd. -

4. What Are the Effects of Education on Health? – 171

4. WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF EDUCATION ON HEALTH? – 171 4. What are the effects of education on health? By Leon Feinstein, Ricardo Sabates, Tashweka M. Anderson, ∗ Annik Sorhaindo and Cathie Hammond ∗ Leon Feinstein, Ricardo Sabates, Tashweka Anderson, Annik Sorhaindo and Cathie Hammond, Institute of Education, University of London, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL, United Kingdom. We would like to thank David Hay, Wim Groot, Henriette Massen van den Brink and Laura Salganik for the useful comments on the paper and to all participants at the Social Outcome of Learning Project Symposium organised by the OECD’s Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI), in Copenhagen on 23rd and 24th March 2006. We would like to thank the OECD/CERI, for their financial support of this project. A great many judicious and helpful suggestions to improve this report have been put forward by Tom Schuller and Richard Desjardins. We are particularly grateful for the general funding of the WBL Centre through the Department for Education and Skills whose support has been a vital component of this research endeavour. We would also like to thank research staff at the Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning for their useful comments on this report. Other useful suggestions were received from participants at the roundtable event organised by the Wider Benefits of Learning and the MRC National Survey of Health and Development, University College London, on 6th December 2005. All remaining errors are our own. MEASURING THE EFFECTS OF EDUCATION ON HEALTH AND CIVIC ENGAGEMENT: PROCEEDINGS OF THE COPENHAGEN SYMPOSIUM – © OECD 2006 172 – 4.1. -

Black Women's Anti-Poverty Organizing In

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History Summer 8-12-2014 It Came from Somewhere and it Hasn’t Gone Away: Black Women’s Anti-Poverty Organizing in Atlanta, 1966-1996 Daniel Horowitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Horowitz, Daniel, "It Came from Somewhere and it Hasn’t Gone Away: Black Women’s Anti-Poverty Organizing in Atlanta, 1966-1996." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/83 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IT CAME FROM SOMEWHERE AND IT HASN’T GONE AWAY: BLACK WOMEN’S ANTI-POVERTY ORGANIZING IN ATLANTA, 1966-1996 by DANIEL M. HOROWITZ Under the Direction of Dr. Cliff Kuhn ABSTRACT Black women formed the first welfare rights organization in Atlanta composed of recipients and continued anti-poverty organizing for decades. Their strategy adapted to the political climate, including the ebb and flow of social movements. This thesis explores how and why that strategy changed as well as how the experiences of the women involved altered ideas of activism and movements. INDEX WORDS: Atlanta, activism, poverty, community organizing, welfare, welfare reform, welfare rights, Hunger Coalition, Up & Out of Poverty IT CAME FROM SOMEWHERE AND IT HASN’T GONE AWAY: Black Women’s Anti-Poverty Organizing in Atlanta, 1966-1996 by Daniel M.