The Most Southerly Record of a Stranded Bowhead Whale, Balaena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Municipal Backyard Compost Bin Program Participants 2011-Present 2018

Municipal Backyard Compost Bin Program Participants 2011-Present 2018 Baie Verte Bay St George Waste Management Committee Cape St George Channel Port au Basques City of St John's Gander Greens Habour Lourdes New-Wes-Valley Northern Peninsula Regional Service Board Paradise Pasadena Sandy Cove Trinity Bay North Twillingate 2017 Baie Verte Carbonear Corner Brook Farm and Market, Clarenville Grand Falls-Windsor Logy Bay-Middle Cove-Outer Cove Makkovik Memorial University, Grenfell Campus Paradise Pasadena Portugal Cove-St. Phillips Robert's Arm Sandy Cove St. Lawrence St. John's Twillingate 2016 2015 Brigus Baie Verte Burin Corner Brook Carmanville Discovery Regional Service Board Comfort Cove - New Stead Happy Valley - Goose Bay Fogo Island Logy Bay - Middle Cove - Outer Cove Gambo Sandy Cove Gander St. John's McIver’s Sunnyside North West River Witless Bay Point Leamington 2014 Burgeo Carbonear Conception Bay South (CBS) Lewisporte Paradise Portugal Cove - St. Phillip’s St. Alban’s St. Anthony (NorPen Regional Service Board) St. George’s St. John's Whitbourne Witless Bay 2013 Bird Cove Kippens Bishop's Falls Lark Harbour Campbellton Marystown Clarenville New Perlican Conception Bay South (CBS) NorPen Regional Service Board Conne River Old Perlican Corner Brook Paradise Deer Lake Pasadena Dover Placentia Flatrock Port au Choix Gambo Portugal Cove-St. Phillips Grand Bank Springdale Happy Valley - Goose Bay Stephenville Harbour Grace Twillingate 2011 Botwood Conception Bay South (CBS) Cape Broyle Conception Harbour Gander Conne River Glovertown Corner Brook Sunnyside Deer Lake Harbour Main – Chapel’s Cove – Gambo Lakeview Glenwood Holyrood Grand Bank Logy Bay Harbour Breton Appleton Heart’s Delight - Islington Arnold’s Cove Irishtown – Summerside Bay Roberts Kippens Baytona Labrador City Bonavista Lawn Campbellton Leading Tickles Carbonear Long Harbour & Mount Arlington Centreville Heights Channel - Port aux Basques Makkovik (Labrador) Colliers Marystown 2011 cont. -

Order CETACEA Suborder MYSTICETI BALAENIDAE Eubalaena Glacialis (Müller, 1776) EUG En - Northern Right Whale; Fr - Baleine De Biscaye; Sp - Ballena Franca

click for previous page Cetacea 2041 Order CETACEA Suborder MYSTICETI BALAENIDAE Eubalaena glacialis (Müller, 1776) EUG En - Northern right whale; Fr - Baleine de Biscaye; Sp - Ballena franca. Adults common to 17 m, maximum to 18 m long.Body rotund with head to 1/3 of total length;no pleats in throat; dorsal fin absent. Mostly black or dark brown, may have white splotches on chin and belly.Commonly travel in groups of less than 12 in shallow water regions. IUCN Status: Endangered. BALAENOPTERIDAE Balaenoptera acutorostrata Lacepède, 1804 MIW En - Minke whale; Fr - Petit rorqual; Sp - Rorcual enano. Adult males maximum to slightly over 9 m long, females to 10.7 m.Head extremely pointed with prominent me- dian ridge. Body dark grey to black dorsally and white ventrally with streaks and lobes of intermediate shades along sides.Commonly travel singly or in groups of 2 or 3 in coastal and shore areas;may be found in groups of several hundred on feeding grounds. IUCN Status: Lower risk, near threatened. Balaenoptera borealis Lesson, 1828 SIW En - Sei whale; Fr - Rorqual de Rudolphi; Sp - Rorcual del norte. Adults to 18 m long. Typical rorqual body shape; dorsal fin tall and strongly curved, rises at a steep angle from back.Colour of body is mostly dark grey or blue-grey with a whitish area on belly and ventral pleats.Commonly travel in groups of 2 to 5 in open ocean waters. IUCN Status: Endangered. 2042 Marine Mammals Balaenoptera edeni Anderson, 1878 BRW En - Bryde’s whale; Fr - Rorqual de Bryde; Sp - Rorcual tropical. -

Cetaceans: Whales and Dolphins

CETACEANS: WHALES AND DOLPHINS By Anna Plattner Objective Students will explore the natural history of whales and dolphins around the world. Content will be focused on how whales and dolphins are adapted to the marine environment, the differences between toothed and baleen whales, and how whales and dolphins communicate and find food. Characteristics of specific species of whales will be presented throughout the guide. What is a cetacean? A cetacean is any marine mammal in the order Cetaceae. These animals live their entire lives in water and include whales, dolphins, and porpoises. There are 81 known species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises. The two suborders of cetaceans are mysticetes (baleen whales) and odontocetes (toothed whales). Cetaceans are mammals, thus they are warm blooded, give live birth, have hair when they are born (most lose their hair soon after), and nurse their young. How are cetaceans adapted to the marine environment? Cetaceans have developed many traits that allow them to thrive in the marine environment. They have streamlined bodies that glide easily through the water and help them conserve energy while they swim. Cetaceans breathe through a blowhole, located on the top of their head. This allows them to float at the surface of the water and easily exhale and inhale. Cetaceans also have a thick layer of fat tissue called blubber that insulates their internals organs and muscles. The limbs of cetaceans have also been modified for swimming. A cetacean has a powerful tailfin called a fluke and forelimbs called flippers that help them steer through the water. Most cetaceans also have a dorsal fin that helps them stabilize while swimming. -

Fall12 Rare Southern California Sperm Whale Sighting

Rare Southern California Sperm Whale Sighting Dolphin/Whale Interaction Is Unique IN MAY 2011, a rare occurrence The sperm whale sighting off San of 67 minutes as the whales traveled took place off the Southern California Diego was exciting not only because slowly east and out over the edge of coast. For the first time since U.S. of its rarity, but because there were the underwater ridge. The adult Navy-funded aerial surveys began in also two species of dolphins, sperm whales undertook two long the area in 2008, a group of 20 sperm northern right whale dolphins and dives lasting about 20 minutes each; whales, including four calves, was Risso’s dolphins, interacting with the the calves surfaced earlier, usually in seen—approximately 24 nautical sperm whales in a remarkable the company of one adult whale. miles west of San Diego. manner. To the knowledge of the During these dives, the dolphins researchers who conducted this aerial remained at the surface and Operating under a National Marine survey, this type of inter-species asso- appeared to wait for the sperm Fisheries Service (NMFS) permit, the ciation has not been previously whales to re-surface. U.S. Navy has been conducting aerial reported. Video and photographs surveys of marine mammal and sea Several minutes after the sperm were taken of the group over a period turtle behavior in the near shore and whales were first seen, the Risso’s offshore waters within the Southern California Range Complex (SOCAL) since 2008. During a routine survey the morning of 14 May 2011, the sperm whales were sighted on the edge of an offshore bank near a steep drop-off. -

Whale Watching New South Wales Australia

Whale Watching New South Wales Australia Including • About Whales • Humpback Whales • Whale Migration • Southern Right Whales • Whale Life Cycle • Blue Whales • Whales in Sydney Harbour • Minke Whales • Aboriginal People & Whales • Dolphins • Typical Whale Behaviour • Orcas • Whale Species • Other Whale Species • Whales in Australia • Other Marine Species About Whales The whale species you are most likely to see along the New South Wales Coastline are • Humpback Whale • Southern Right Whale Throughout June and July Humpback Whales head north for breading before return south with their calves from September to November. Other whale species you may see include: • Minke Whale • Blue Whale • Sei Whale • Fin Whale • False Killer Whale • Orca or Killer Whale • Sperm Whale • Pygmy Right Whale • Pygmy Sperm Whale • Bryde’s Whale Oceans cover about 70% of the Earth’s surface and this vast environment is home to some of the Earth’s most fascinating creatures: whales. Whales are complex, often highly social and intelligent creatures. They are mammals like us. They breath air, have hair on their bodies (though only very little), give birth to live young and suckle their calves through mammary glands. But unlike us, whales are perfectly adapted to the marine environment with strong, muscular and streamlined bodies insulated by thick layers of blubber to keep them warm. Whales are gentle animals that have graced the planet for over 50 million years and are present in all oceans of the world. They capture our imagination like few other animals. The largest species of whales were hunted almost to extinction in the last few hundred years and have survived only thanks to conservation and protection efforts. -

Species Assessment for North Atlantic Right Whale

Species Status Assessment Class: Mammalia Family: Balaenidae Scientific Name: Eubalaena glacialis Common Name: North Atlantic right whale Species synopsis: The North Atlantic right whale, which was first listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 1973, is considered to be critically endangered (Clapham et al 1999, NMFS 2013). The western population of North Atlantic right whales (NARWs or simply right whales) has seen a recent slight increase. The most recent stock assessment gives a minimum population size of 444 animals with a growth rate of 2.6% per year (NMFS 2013). It is believed that the actual number of right whales is about 500 animals (Pettis 2011, L. Crowe, pers. comm.). At this time, the species includes whales in the North Pacific and the North Atlantic oceans (NMFS 2005). However, recent genetic evidence showed that there were at least three separate lineages of right whales, and there are now three separate species that are recognized. These three species include: the North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis), which ranges in the North Atlantic Ocean; the North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica), which ranges in the North Pacific Ocean; and the southern right whale (Eubalaena australis), which ranges throughout the Southern Hemisphere (NMFS 2005). The distribution of right whales is partially determined by the presence of its prey, which consists of copepods and krill (Baumgartner et al 2003). Most of the population migrates in the winter to calving grounds from in low latitudes from high latitude feeding grounds in the spring and summer. A portion of the population does not migrate to the calving grounds during the winter and it is unknown where they occur during that season (NMFS website, NMFS 2013). -

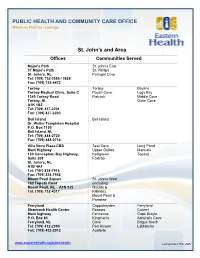

St. John's and Area

PUBLIC HEALTH AND COMMUNITY CARE OFFICE Where to Find Us - Listings St. John’s and Area Offices Communities Served Major’s Path St. John’s East 37 Major’s Path St. Phillips St. John’s, NL Portugal Cove Tel: (709) 752-3585 / 3626 Fax: (709) 752-4472 Torbay Torbay Bauline Torbay Medical Clinic, Suite C Pouch Cove Logy Bay 1345 Torbay Road Flatrock Middle Cove Torbay, NL Outer Cove A1K 1B2 Tel: (709) 437-2201 Fax: (709) 437-2203 Bell Island Bell Island Dr. Walter Templeton Hospital P.O. Box 1150 Bell Island, NL Tel: (709) 488-2720 Fax: (709) 488-2714 Villa Nova Plaza-CBS Seal Cove Long Pond Main Highway Upper Gullies Manuels 130 Conception Bay Highway, Kelligrews Topsail Suite 208 Foxtrap St. John’s, NL A1B 4A4 Tel: (70(0 834-7916 Fax: (709) 834-7948 Mount Pearl Square St. John’s West 760 Topsail Road (including Mount Pearl, NL A1N 3J5 Goulds & Tel: (709) 752-4317 Kilbride), Mount Pearl & Paradise Ferryland Cappahayden Ferryland Shamrock Health Center Renews Calvert Main highway Fermeuse Cape Broyle P.O. Box 84 Kingman’s Admiral’s Cove Ferryland, NL Cove Brigus South Tel: (709) 432-2390 Port Kirwan LaManche Fax: (709) 432-2012 Auaforte www.easternhealth.ca/publichealth Last updated: Feb. 2020 Witless Bay Main Highway Witless Bay Burnt Cove P.O. Box 310 Bay Bulls City limits of St. John’s Witless Bay, NL Bauline to Tel: (709) 334-3941 Mobile Lamanche boundary Fax: (709) 334-3940 Tors Cove but not including St. Michael’s Lamanche. Trepassey Trepassey Peter’s River Biscay Bay Portugal Cove South St. -

AMC ADVENTURE TRAVEL Volunteer-Led Excursions Worldwide

AMC ADVENTURE TRAVEL Volunteer-Led Excursions Worldwide Newfoundland – Hike and Explore the East Coast Trail June 18 - 28, 2022 Trip #2248 Cape Spear, Newfoundland (photo from Wikipedia), Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Trip Overview Are you looking for a hiking adventure that combines experiencing spectacular coastal trails, lighthouses, sea spouts, a boat tour with bird sightings, and potential whales and iceberg viewing? Or enjoy a morning kayaking around a bay? Sounds exciting, then come join us on our Newfoundland Adventure to hike parts of the East Coast Trail, explore and enjoy the spectacular views from the most eastern point of North America. Birds love Newfoundland and we will have the opportunity to see many. Newfoundland is known as the Seabird Capital of North America and Witless Bay Reserve boasts the largest colony of the Atlantic Puffin. Other birds we may see are: Leach’s Storm Petrels, Common Murre, Razorbill, Black Guillemot, and Black-legged Kittiwake, to name a few. Newfoundland is one of the most spectacular places on Earth to watch whales. The world’s largest population of Humpback whales returns each year along the coast of Newfoundland and an additional 21 species of whales and dolphins visit the area. We will have potential to see; Minke, Sperm, Pothead, Blue, and Orca whales. Additionally we will learn about its history, enjoy fresh seafood and walk around the capital St. John’s. This will be an Adventure that is not too far from our northern border. -

North Atlantic Right Whales: BOSTON & BREWSTER

A Series of Special Talks in BOSTON & BREWSTER LECTURE SERIES -- North Atlantic Right Whales: Sponsored by: Whale and Dolphin A Critically Endangered Species in our Backyard Conservation Society (N.A.) www.whales.org There are no Wrong Whales or Left Whales, but there are Right Whales -- and they are found in our backyard. These behemoths, measuring up to 50 feet long and 50 tons, visit Massachusetts NOAA’s Stellwagen Bank and Cape Cod Bays and Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary to feed in our rich waters. National Marine Sanctuary But with less than 400 animals in the population, the North Atlantic Right Whale is critically endan- stellwagen.noaa.gov gered. The Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (N.A.) and Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary are proud to present these leading experts who will discuss ongoing studies of right whale biology and behavior, and conservation efforts to save this species from extinction. ALL PROGRAMS START AT 7PM. Additional support March 7 (Brewster) Grappling with Giants: Disentangling large whales and provided by: March 12 (Boston) understanding entanglement -- Scott Landry, Provincetown Cape Cod Museum of Center for Coastal Studies Natural History Entanglement in fi shing gear is a major threat to right whales; and with so few animals in Urban Harbors Institute, the population, any losses threaten survival of the species. Through careful removal of UMass/Boston fi shing gear entangling whales, questions about how whales become entangled are brought North Atlantic Right Whale into focus. Mr. Landry, who leads the center’s disentanglement team, will use case histories Consortium to explore the nature of entanglements, disentanglement techniques (including some derived from whaling methods), and possible fi shing practices that could reduce bycatch. -

Report of the Workshop on Assessing the Population Viability of Endangered Marine Mammals in U.S

Report of the Workshop on Assessing the Population Viability of Endangered Marine Mammals in U.S. Waters 13–15 September 2005 Savannah, Georgia Prepared by the Marine Mammal Commission 2007 This is one of five reports prepared in response to a directive from Congress to the Marine Mammal Commission to assess the cost-effectiveness of protection programs for the most endangered marine mammals in U.S. waters TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary.............................................................................................................v I. Introduction..............................................................................................................1 II. Biological Viability..................................................................................................1 III. Population Viability Analysis..................................................................................5 IV. Viability of the Most Endangered Marine Mammals ..............................................6 Extinctions and recoveries.......................................................................................6 Assessment of biological viability...........................................................................7 V. Improving Listing Decisions..................................................................................10 Quantifying the listing process ..............................................................................10 -

City Plan 2010

CITY PLAN 2010 Mount Pearl Municipal Plan 2010 GAZETTED – DECEMBER 23, 2011 Revised – November 4, 2016 – As a Result of Amendment No. 17, 2016 Please Note: This is not the official copy of the aforementioned Municipal Plan, but rather a consolidated copy to include amendments. The Municipal Plan is subject to periodic amendments. Please contact the City of Mount Pearl Planning and Development Department for information relating to recent amendments. CITY OF MOUNT PEARL Planning and Development Department 3 Centennial Street Mount Pearl, NL A1N 1G4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1 1.1. Municipal Planning in the City of Mount Pearl ............................................. 1 1.2. Purpose of the Municipal Plan ....................................................................... 2 1.3. Legal Basis and Authority of the Municipal Plan .......................................... 2 1.4. Planning Area of the Municipal Plan ............................................................. 4 1.5. Municipal Plan Review Process ..................................................................... 4 1.6. Adoption and Approval of the Municipal Plan .............................................. 6 1.7. The Legal Effect of the Municipal Plan ......................................................... 6 1.8. The Development Regulations ....................................................................... 6 1.9. Other Plans, Development Schemes, and Studies ........................................ -

Population Histories of Right Whales (Cetacea: Eubalaena) Inferred from Mitochondrial Sequence Diversities and Divergences of Their Whale Lice (Amphipoda: Cyamus)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce U.S. Department of Commerce 2005 Population histories of right whales (Cetacea: Eubalaena) Inferred from Mitochondrial Sequence Diversities and Divergences of Their Whale Lice (Amphipoda: Cyamus) Zofia A. Kaliszewska Harvard University Jon Seger University of Utah Victoria J. Rowntree Ocean Alliance/Whale Conservation Institute, Lincoln, Massachusetts & Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas, Miñones 1986, Buenos Aires , Argentina Amy R. Knowlton Ocean Alliance/Whale Conservation Institute, Lincoln, Massachusetts & Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas, Miñones 1986, Buenos Aires, Argentina Kim Marshalltilas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub Ocean Alliance/Whale Conservation Institute, Lincoln, Massachusetts, & Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas, Part of Buenos the Envir Aironmentales, Argentina Sciences Commons See next page for additional authors Kaliszewska, Zofia A.; Seger, Jon; Rowntree, Victoria J.; Knowlton, Amy R.; Marshalltilas, Kim; Patenaude, Nathalie J.; Rivarola, Mariana; Schaeff, Catherine M.; Sironi, Mariano; Smith, Wendy A.; Yamada, Tadasu K.; Barco, Susan G.; Benegas, Rafael; Best, Peter B.; Brown, Moira W.; Brownell, Robert L. Jr.; Harcourt, Robert; and Carribero, Alejandro, "Population histories of right whales (Cetacea: Eubalaena) Inferred from Mitochondrial Sequence Diversities and Divergences of Their Whale Lice (Amphipoda: Cyamus)" (2005). Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce. 88. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub/88 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Commerce at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S.