A Voyage Around My Father

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signumclassics

126booklet 13/5/08 11:28 Page 1 ALSO AVAILABLE ON signumclassics Ragtime & Blue Brahms and Schumann Haydn Piano Sonatas Elena Kats-Chernin - Piano John Lill - Piano John Lill - Piano SIGCD058 SIGCD075 SIGCD097 Elena Kats-Chernin is a composer who Much-loved pianist, John Lill, plays John Lill returns to take the listener on a defies categorisation: a virtuosic pianist touchstones of the 19th-century romantic journey through the many moods of Haydn, and improviser, her compositions flow piano tradition. Lill is at his sparkling in brilliant performances of some from her like a fountain. This CD is best in this wonderful repertoire. composer’s most intriguing works for drawn from the small works she often the keyboard. writes for her own enjoyment - a cornucopia of rags, blues and heart- melting melodies. Available through most record stores and at www.signumrecords.com For more information call +44 (0) 20 8997 4000 126booklet 13/5/08 11:28 Page 3 MESSIAEN: CHAMBER WORKS MESSIAEN: CHAMBER WORKS The general perception of Messiaen is of a always turned up at class with mountains of work 1. Fantaisie [8.59] composer who lived in some rarefied atmosphere (not guaranteed to ensure popularity!) and was of his own, floating far above the mundane, recognised as a young man likely to succeed. But Quatuor pour la fin du Temps material world. Given his preoccupation with any view of Messiaen as vague or indecisive in his 2. Liturgie de cristal [2.37] esoteric rhythms, sound-colours, theology and opinions needs to be set against the truth - for all birdsong, this is perhaps a reasonable judgment his pacific demeanour (and, in later years, 3. -

Di Xiao Piano

Di’s international career started at 17 when she played Chengzong Di Xiao Yin’s Yellow River Piano Concerto in Kuala Lumpur and Penang for the Malaysian Royal Family. Piano Subsequently Di has been invited to perform as a soloist in many Described as “a pianist of countries including Malaysia, Ukraine, Singapore, India, China awesome gifts” and compared to and the UK. In the UK, her concert Clara Schumann by the critics, performances have received much Chinese pianist Di Xiao concluded a acclaim. Her debut at Symphony major international recital tour in Hall Birmingham in 2006 was 2009 representing the UK as part of described by the UK Chinese Times the universally acclaimed 'Rising as “A stunning concert!” and an Stars' series. The tour included sell early performance of the Schumann out concerts at the Concertgebouw Concerto prompted The Birmingham Amsterdam, Vienna Konzerthaus, Post to say “In her graceful, dancing Salzburg Mozartium, Stockholm finale it was easy to imagine Clara Konserthaus and Luxembourg Schumann at the keyboard.” Di has Philharmonie. Following her Köln appeared in a number of important Philharmoie recital, played to an Career Highlights music festivals including Breman audience of over 1000, the press Musikfest (Germany), New • Performed “Yellow River stated that “Di Xiao presents a Generation Arts Festival (UK), Concerto” for Malaysian demanding programme that takes Buxton Arts Festival (UK) and Royal Family at Kuala your breath away.” As the tour Leamington Music Festival (UK). In Lumpur aged 17. progressed she went on to thrill October 2010 Di conducted a tour of audiences at Symphony Hall and China during which she played for • Birmingham Symphony Town Hall Birmingham, Brussels the enormous inaugural Classical Hall Debut, 2006. -

RCM International Student Guide.Pdf

INTERNATIONAL STUDENT GUIDE TOP WITH MORE THAN CONSERVATOIRE FOR 800 PERFORMING ARTS STUDENTS IN THE UK, SECOND IN FROM MORE THAN EUROPE AND JOINT THIRD IN THE WORLD QS WORLD UNIVERSITY RANKINGS 2016 60 COUNTRIES THE RCM IS AN INTERNATIONAL LOCATED OPPOSITE THE COMMUNITY ROYAL IN THE HEART OF LONDON ALBERT HALL HOME TO THE ANNUAL TOP UK SPECIALIST INSTITUTION BBC PROMS FESTIVAL FOR MUSIC COMPLETE UNIVERSITY GUIDE 2017 100% OF SURVEY RESPONDENTS IN OVER OF EMPLOYMENT OR 40% FURTHER STUDY STUDENTS BENEFIT FROM SIX MONTHS AFTER GRADUATION FOR SCHOLARSHIPS THREE CONSECUTIVE YEARS HIGHER EDUCATION STATISTICS AGENCY SURVEY CONCERTS AND MASTERCLASSES TOP LONDON WATCHED IN CONSERVATOIRE COUNTRIES FOR WORLD-LEADING WORLDWIDE IN 2014 75 RESEARCH VIA THE RCM’s RESEARCH EXCELLENCE FRAMEWORK YOUTUBE CHANNEL 2 ROYAL COLLEGE OF MUSIC / WWW.RCM.AC.UK WELCOME The Royal College of Music is one of the world’s greatest conservatoires, training gifted musicians from all over the globe for a range of international careers as performers, conductors and composers. We were proud to be ranked the top conservatoire for performing arts in the UK, second in Europe and joint third in the world in the 2016 QS World University Rankings. The RCM provides a huge Founded in 1882 by the future King Edward VII, number of performance the RCM has trained some of the most important opportunities for its students. figures in British and international music life. We hold more than 500 Situated opposite the Royal Albert Hall, our events a year in our building and location are the envy of the world. -

Monday Playlist

June 24, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “I pay no attention whatever to anybody's praise or blame. I simply follow my own feelings” — WA Mozart Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Saint-Saëns Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso, Op. 28 Perlman/Paris Orchestra/Martinon EMI 47725 077774772525 Fournier/Lucerne Festival 00:11 Buy Now! Haydn Cello Concerto No. 1 in C DG 289 469 148 028946914823 Strings/Baumgartner 00:37 Buy Now! Glazunov The Sea (Orchestral Fantasy in E), Op. 28 Moscow Symphony/Golovschin Naxos 8.553512 730099451222 01:00 Buy Now! Mozart Overture ~ La Finta Semplice, K. 46a Calgary Philharmonic/Bernardi CBC 5149 059582514924 Nimbus 01:08 Buy Now! Rachmaninoff Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor, Op. 36 John Lill 5348 083603534820 Records 01:36 Buy Now! Beethoven Symphony No. 8 in F, Op. 93 Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich/Zinman Arte Nova 56341 743215634126 02:01 Buy Now! Schumann Manfred Overture, Op. 115 Cleveland Orchestra/Szell Sony Classical 62349 074646234921 02:13 Buy Now! Rubbra Symphony No. 2, Op. 45 BBC National Orchestra of Wales/Hickox Chandos 9481 095115948125 Colpron/Kraemer/Les Boréades de 02:48 Buy Now! Telemann Concerto in E minor for flute, violin and strings ATMA ACD 2 2193 722056219327 Montréal 02:59 Buy Now! Delibes Swanilda’s Waltz ~ Coppelia Berlin Philharmonic/Karajan DG 423 215 028942321526 03:04 Buy Now! Mozart Twelve Variations in C, K. 179 Ingrid Haebler Philips 422 726 028942251823 03:23 Buy Now! Borodin Symphony No. -

Concert Series Newsletter November 2014

MARLBOROUGH COLLEGE CONCERT SERIES NEWSLETTER NOVEMBER 2014 John Lill RapturousCollege Chapel reception to host for Nash Ensemble recital Wells Cathedral Choir The 2014-2015 Marlborough College Concert Series opened with a magnificent performance by the Nash Ensemble celebrating its 50th year and, to judge only by the captivated attention of the audience including 35 music students from the College, the original members of the Ensemble should have been hugely proud of the legacy that they have left. This was ensemble playing at its best and what came through so strikingly was not simply the hours of work that must have gone into the performance but rather the time spent on interpret- ation. It was a wonderfully contrasting programme which provided all the colours, the emotions, the sensitivities Music from the ‘Romantic’ era and at times the bravado of chamber music which could only have been properly interpreted by playing of the This month John Lill will perform solo works for highest quality, as we witnessed. From the gentle opening bars of piano from late 18th and 19th century Vienna Mahler’s Piano Quartet in A minor to the final ecstatic bars of Elgar’s Piano Quintet in the same key, via Felix Unanimously described as the leading all of which with the exception of a Mendelssohn’s Piano Trio in D Minor pianist of his generation, John Lill’s rare piece by Prokofiev were composed in there was an intensity in the perform- talent began to emerge in 1953, when Vienna between the late 18th and 19th ance that drew the audience in to he gave his first public recital at the age centuries. -

Download Booklet

570531bk Arnold US 14/8/07 9:37 am Page 5 Esa Heikkilä 8.570531 The Finnish conductor Esa Heikkilä has been appointed Chief Conductor of the Joensuu City Orchestra (Joensuun British Piano Concertos Kaupunginorkesteri) in Finland from January 2008, adding this appointment to his positions as Artistic Director of DDD Symphony Orchestra Vivo (Finland’s national youth orchestra) and as Senior Lecturer for Orchestra and Chamber Music at the Lahti Polytechnic’s Faculty of Music. He passed his final Sibelius Academy conducting diploma concert in March 2004 with the highest possible mark. He has appeared with the Sinfonia Lahti, the Turku Sir Malcolm Philharmonic, the Tampere Philharmonic and Oulu Philharmonic orchestras, the Jyväskylä Symphony Orchestra, Joensuu City Orchestra, Kymi Sinfonietta, Pori Sinfonietta, Lappeenranta City Orchestra and Mikkeli City Orchestra. He has been invited to conduct nearly all of Finland’s orchestras in concert and recordings, as well as ARNOLD acting as assistant to Leif Segerstam in Germany and Lithuania, Mikko Franck and the Belgian National Orchestra, and Osmo Vänskä with Sinfonia Lahti. Outside Finland he has conducted the Haapsalu Festival Orchestra in Estonia for two years and made successful débuts with the Ulster Orchestra in Belfast in October 2004, the Iceland Concerto for Two Pianos (Three Hands) Symphony Orchestra in February 2005 and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra of Flanders in March 2005. He was immediately re-invited to the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra after making his début with them in February 2006, by the BBC in Northern Ireland after a first engagement there in January 2007, and he returns to Iceland for Concerto for Piano Duet a third time in October 2007. -

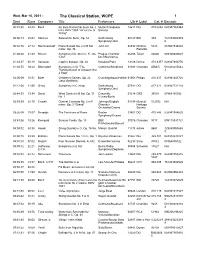

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Wed, Mar 10, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 03:43 Bach Air from Orchestral Suite No. 3 Mutter/Trondheim 12617 DG 479 6834 028947968344 in D, BWV 1068 "Air on the G Soloists String" 00:06:1325:03 Sibelius Swanwhite Suite, Op. 54 Gothenburg 00127 BIS 359 731859000359 Symphony/Jarvi 6 00:32:1627:12 Rachmaninoff Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat John Lill 02892 Nimbus 5348 083603534820 minor, Op. 36 Records 01:00:5831:39 Mozart Symphony No. 36 in C, K. 425 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 “Linz” Orch/Mackerras 01:33:3705:18 Sarasate Caprice basque, Op. 24 Kavakos/Pace 13126 Decca 478 9377 028947893776 01:39:55 18:44 Dittersdorf Symphony in G, "The Cantilena/Shepherd 01399 Chandos 8564/5 501468285642 Transformation of Actaeon into 3 a Stag" 02:00:0910:51 Bizet Children's Games, Op. 22 Concertgebouw/Haitink 01008 Philips 416 437 028941643728 (Jeux d'enfants) 02:12:0031:55 Grieg Symphony in C minor Gothenburg 07392 DG 427 321 028942732124 Symphony/Jarvi 02:44:5513:34 Danzi Wind Quintet in B flat, Op. 51 Ensemble 01218 CBS 39558 07464395582 No. 1 Vienna-Berlin 02:59:5925:10 Crusell Clarinet Concerto No. 2 in F Johnson/English 01198 Musical 512072 N/A minor, Op. 5 "Grand" Chamber Heritage Orchestra/Groves Society 03:26:09 15:57 Respighi The Fountains of Rome Boston 01401 DG 415 846 028941584625 Symphony/Ozawa 03:43:0619:26 Korngold Sursum Corda, Op. 13 BBC 07976 Chandos 9317 095115931721 Philharmonic/Bamert 04:04:02 24:38 Haydn String Quartet in G, Op. -

A History of Music at Eastbourne College from Its Foundation in 1867 Until the Opening of the Birley Centre

A history of music at Eastbourne College from its foundation in 1867 until the opening of the Birley Centre Last updated 30 September 2020 This is a work in progress and updates will be made as new information comes to light 1 A history of music at Eastbourne College from its foundation in 1867 until the opening of the Birley Centre Contents Introduction 2 Bibliography 3 Directors, assistant directors, organists and other full-time 4 music staff Preface 7 The early years 8 Frank Gil 11 From 1914 to the 1920s 14 Renaissance 16 The war years and exile at Radley 20 Post-war reconstruction 22 The Birley years begin 29 John Walker arrives 31 The 1970s 34 The 1980s 40 The 1990s 45 The new millennium 52 The year is 2011 and the Birley Centre opens a new era 67 Appendix: List of College musicians 72 2 Introduction The aim of this history is to put into perspective a rich part of the story of Eastbourne College and was begun at a time when a new multi-million pound whole-school building which will house a state-of-the-art music school was [and was completed in summer 2011]. It has helped some of those who have been involved with this project to learn much about what has happened musically to bring us to where we are now and has reminded us of key events and characters at a time when we celebrated d publishing a book, Eastbourne College: A Celebration, bringing together reminiscences of those who know and have known the college in whatever capacity, and which was published on speech day 2007). -

Past Concerts

CONCERTS 1990/2015 1 2013/14 Mote Hall / 12 October 2013 Laura van der Heijden (cello) MSO / Wright PAST CONCERTS - 1990/2015 Britten – Four Sea Interludes from “Peter 2014/15 Grimes” Elgar – Cello Concerto Mote Hall / 11 October 2014 Rachmaninov – Symphony 3 Tae-Hyung Kim (piano) MSO / Wright Mote Hall / 30 November 2013 Wagner – Overture Tannhäuser Tom Bettley (horn) Beethoven – Piano Concerto 5 MSO / Wright “Emperor” Berlioz – Overture, Roman Carnival Tchaikovsky – Symphony 1 “Winter Glière – Horn Concerto Daydreams” Richard Strauss – Death and Transfiguration Mote Hall / 29 November 2014 Stravinsky – Suite, The Firebird Giovanni Guzzo (violin) MSO / Wright Mote Hall / 1 February 2014 Copland – Appalachian Spring Emma Johnson (clarinet) replacing the Brahms – Violin Concerto indisposed Mark Simpson Vaughan Williams – Symphony 4 MSO / Wright Mendelssohn – Overture, The Hebrides Mote Hall / 31 January 2015 Sibelius – Valse Triste Harry Winstanley (flute) Finzi – Clarinet Concerto MSO / Wright Beethoven – Symphony 3 “Eroica” Weber – Overture, Der Freischütz Taffanel orch. Winstanley – Fantasy on Mote Hall / 22 March 2014 themes from Weber’s Der Freischütz Bartosz Woroch (violin) Nielsen – Flute Concerto MSO / Wright Dvorak – Symphony 6 Schumann – Overture, Manfred Beethoven – Violin Concerto Mote Hall / 21 March 2015 Sibelius – Symphony 5 Bartosz Woroch (violin) replacing the indisposed Ulf Hoelscher Mote Hall / 17 May 2014 MSO / Wright Tom Poster (piano) Berlioz – Overture, Le Corsaire MSO / Wright Elgar – Violin Concerto Ravel – Suite, -

Hitting the Right Note Inside the Royal College of Music’S New Percussion Suite

The Magazine for the Royal College of MusicI Autumn 2015 Hitting the Right Note Inside the Royal College of Music’s new percussion suite... What’s inside... Welcome to upbeat... The Royal College of Music welcomed new and returning staff and students this term after a summer break which saw a number of exciting developments. Contents The Durrington Room on the fourth floor of the South Building has been 4 In the news renovated into a new purpose-built percussion suite – see page ten to find out more from Head of Percussion David Hockings. The state-of-the-art Amadeus The latest news from the RCM, practice pods that were in the courtyard have been moved to the third floor Ziff including the recent visit of the Suite and the remaining practice rooms have been refurbished. First Lady of China, a tribute to former RCM Director Sir David Meanwhile, improvements to the Blomfield Building include the creation of a new Willcocks and the launch of the performance space on the ground floor. The Corelli Room encompasses the old Royal College of Music’s Creative G15 and G16 rooms and will hold chamber concerts, lectures and classes. Careers Centre... This issue, we also look at how young musicians at the RCM are supported 10 Percussive Progress through scholarships. Turn to page 12 for an interview with pianist Martin James Head of Percussion David Bartlett and his supporter Terry Hitchcock to find out more about this valuable Hockings describes the exciting programme. development of a brand new The Royal College of Music is delighted to announce that the RCM Symphony percussion suite in the South Orchestra will return to the Royal Festival Hall in 2016. -

NEWS RELEASE Umass Amherst Fine Arts Center

NEWS RELEASE UMass Amherst Fine Arts Center www.fineartscenter.com CONTACT: Jorge Luis González at 413-545-4482 or [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: March 23, 2009 WHAT: Fine Arts Center Presents National Philharmonic of Russia Sunday, April 19, 7PM Fine Arts Center Concert Hall Tickets available at 545-2511 or 800-999-UMAS or online at www.fineartscenter.com. IMAGES: To download images relating to this press release go online to: http://www.umass.edu/fac/centerseries/pressreleases/photo.html National Philharmonic of Russia To Present an All-Russian Program at UMass Fine Arts Center Concert Hall Amherst, Mass.--Composed of Russia’s leading symphonic virtuosos and led by the electrifying conductor and violinist Vladimir Spivakov, the National Philharmonic of Russia will present a thrilling all-Russian program at the UMass Fine Arts Center Concert Hall on Sunday, April 19 at 7 PM. As its name suggests, the National Philharmonic of Russia (NPR) is not only a major musical institution, but also a cultural ambassador for post-reconstruction Russia. The orchestra will be joined by guest pianist Valentina Lisitsa. The evening's program features works by Anatol Liadov, Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev, and, with Lisitsa on the piano, Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 1 in F- sharp Minor. There will be a pre-performance talk by Lonfranco Marcelletti at 6:15 PM in the Concert Hall lobby. Created with generous support from Russia’s Cultural Ministry, the NPR was founded in January 2003 as commissioned by President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin. The orchestra symbolizes the deep commitment the country maintains to its rich cultural traditions, as well as the bold steps it is taking towards an innovative and dynamic future. -

An Investigation of Music and Paranormal Phenomena

PARAMUSICOLOGY: AN INVESTIGATION OF MUSIC AND PARANORMAL PHENOMENA Melvyn J. Willin Ph. D. Music Department University of Sheffield February 1999 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk THESIS CONTAINS TAPE CASSETTE PARAMUSICOLOGY: AN INVESTIGATION OF MUSIC AND PARANORMALPBENOMENA Melvyn J. Willin SUMMARY The purpose of this thesis is to explore musical anomalies that are allegedly paranormal in origin. From a wide range of categories available, three areas are investigated: • music and telepathy • music written by mediums professedly contacted by dead composers • music being heard where the physical source of sound is unknown and presumed to be paranormal. In the first part a method of sensory masking (referred to as ganzfeld) is used to study the possibility of the emotional or physical content of music being capable of mind transference. A further experiment presents additional results relating to the highest scoring individuals in the previous trials. No systematic evidence for the telepathic communication of music was found. In the second section a number of mediums and the music they produced are investigated to examine the truthfulness of their claims of spiritual intervention in compositions and performances. Methods of composition are investigated and the music is analysed by experts. For the final part of the thesis locations are specified where reports of anomalous music have been asserted and people claiming to have heard such music are introduced and their statements examined. Literature from a variety of data bases is considered to ascertain whether the evidence for paranormal music consists of genuine material, misconceived perceptions or fraudulent claims.