UNIVERSAL BRAND PERSONALITIES: a Cross-Cultural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Ability to Investigate Steroid Use in Major League

LeCrom et al. Page 32 THE IMPACT OF NIKE PROJECT 40/GENERATION ADIDAS PLAYERS ON MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER Carrie W. LeCrom, John P. Selwood, Philipp Daldrup, & Mark Driscoll Carrie LeCrom, Ph.D., is the Director Abstract of Instruction and Academic Affairs at Created in 1997, the Nike Project40/Generation Adidas program encourages soccer players the Center for Sport to leave college early to sign professional contracts with Major League Soccer teams, Leadership at VCU. guaranteeing them a 3-year salary with two one-year options. In theory, if the best players Jay Selwood is the are being chosen to this program each year, they should be outperforming those who are Soccer Program drafted to MLS teams but are not a part of the program. By comparing the top draft picks Manager at the Maryland SoccerPlex within and outside the program, researchers hoped to determine whether Nike/Adidas in Boyds, Maryland. players were having a different impact on the league than their counterparts. Results showed Philipp Daldrup is a that, of 15 statistical categories analyzed, only three resulted in a statistically significant Marketing Manager difference between groups. Though Nike/Adidas players were outperforming players who at BASF Coatings were not a part of the program, they were not doing so at a rate to justify the claim that they GmbH in Münster, Germany. have a greater impact on the league. Mark J. Driscoll, M.Ed., is the Assistant Box Office Keywords: Major League Soccer, Nike Project 40, Generation Adidas, MLS SuperDraft Manager at the John Paul Jones Arena in Charlottesville, LeCrom, C. -

PHILADELPHIA UNION V PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept

PHILADELPHIA UNION v PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept. 10, PPL Park, 7:30 p.m. ET) 2011 SEASON RECORDS PROBABLE LINEUPS ROSTERS GP W-L-T PTS GF GA PHILADELPHIA UNION Union 26 8-7-11 35 35 30 1 Faryd Mondragon (GK) at home 13 5-1-7 22 19 15 3 Juan Diego Gonzalez (DF) 18 4 Danny Califf (DF) 5 Carlos Valdes (DF) Timbers 26 9-12-5 32 33 41 MacMath 6 Stefani Miglioranzi (MF) on road 12 1-8-3 6 7 22 7 Brian Carroll (MF) 4 5 8 Roger Torres (MF) LEAGUE HEAD-TO-HEAD 25 Califf Valdes 15 9 Sebastien Le Toux (FW) ALL-TIME: 10 Danny Mwanga (FW) Williams G Farfan Timbers 1 win, 1 goal … 7 11 Freddy Adu (MF) Union 0 wins, 0 goals … Ties 0 12 Levi Houapeu (FW) Carroll 13 Kyle Nakazawa (MF) 14 Amobi Okugo (MF) 2011 (MLS): 22 9 15 Gabriel Farfan (MF) 5/6: POR 1, PHI 0 (Danso 71) 11 16 Veljko Paunovic (FW) Mapp Adu Le Toux 17 Keon Daniel (MF) 18 Zac MacMath (GK) 19 Jack McInerney (FW) 16 10 21 Michael Farfan (MF) 22 Justin Mapp (MF) Paunovic Mwanga 23 Ryan Richter (MF) 24 Thorne Holder (GK) 25 Sheanon Williams (DF) UPCOMING MATCHES 15 33 27 Zach Pfeffer (MF) UNION TIMBERS Perlaza Cooper Sat. Sept. 17 Columbus Fri. Sept. 16 New England PORTLAND TIMBERS Fri. Sept. 23 at Sporting KC Wed. Sept. 21 San Jose 1 Troy Perkins (GK) 2 Kevin Goldthwaite (DF) Thu. Sept. 29 D.C. United Sat. Sept. 24 at New York 11 7 4 Mike Chabala (DF) Sun. -

U12 Boys Generation Adidas Cup Atlanta, Georgia November 29 – December 1, 2019

U12 Boys Generation Adidas Cup Atlanta, Georgia November 29 – December 1, 2019 Day 1 The Whitecaps Academy Centre team composing of 9 players from the Alberta Whitecaps Academy Centre network and 1 player from the Saskatchewan Academy Centre network arrived in Georgia, Atlanta to compete at the U12 MLS Generation Adidas Cup competition. The team were placed in the MLS Affiliate division in a group consisting of Minnesota United, Houston Dynamo and DC United. The boys opened up their tournament with games against Minnesota United and Houston Dynamo. Both teams proved to be excellent opposition for the boys but they held their own and scored a couple of goals through Osagie Aihobaku and Milan Patik. Osagie scored an excellent individual goal while Milan Patik finished off a clever team move. The games were played at a tempo and intensity that challenged the boys in all pillars of the game. Day 2 The boys had an early start for the first of three games. They played against DC United and got their reward for some excellent work out of possession through a goal from Dominic Joseph. DC United came back though in the second half and deservedly scored a couple of goals. Whitecaps then played against Boise Timbers in the play offs and despite not playing particularly well in this game, the boys managed to grind out a win on penalty kicks after a tie. Osagie scoring another skillful goal in this game. The team then saved their best performance for the semi-final against New York Red Bulls. Matching their skillful opponents, the game swung to and fro with chances at either end. -

Download a Copy of the 2019 Soccer

“To Catch a Foul Ball You Need a Ticket to the Game” - Dr. G. Lynn Lashbrook January 11-12, 2019 DURING THE MLS SuperDraft The Global Leader in Sports Business Education | SMWW.com SOCCER CAREER CONFERENCE AGENDA NOTES Friday, January 11th 10am-noon Registration open at Marriott Marquis 11:30am-3pm MLS Super Draft at McCormick Place 4-6:00pm SMWW Welcome Reception at Kroll’s South Loop, 1736 S Michigan Ave Saturday, January 12th - Conference @ Marriott Marquis 8:00am PRE-GAME: Registration Opens 8:45am KICK-OFF: Welcome and Opening Remarks Dr. Lynn Lashbrook, SMWW President & Founder Dr. Lashbrook, President & Founder of Sports Management Worldwide, the first ever online sports management school with a mission to educate sports business executives. SMWW, under Dr. Lashbrook’s guidance, offers a global sports faculty with students from over 162 countries. In addition, Dr. Lashbrook is an NFL registered Agent having personally represented over 100 NFL clients including current Miami Dolphins Quarterback Matt Moore and Minnesota Vikings Quarterback, Kyle Sloter. Lynn is President of the SMWW Agency with over 200 Agent Advisors worldwide representing hundreds of athletes. Dr. Lashbrook continues to spearhead an effort to bring Major League Baseball to Portland, Oregon. He led the lobbying efforts that resulted in a $150 million construction bill for a new baseball stadium. Under his leadership, the group secured legislative action to subsidize a new stadium with ballplayers payroll taxes. Due to this campaign, a 25,000- seat stadium in the heart of the city was revitalized rather than torn down, now home to the MLS Portland Timbers. -

Eligibility Rules

Chapter 6 Christopher R. Deubert I. Glenn Cohen Holly Fernandez Lynch Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School Eligibility Rules Each of the leagues has rules governing when individuals become eligible to play in their leagues. While we fully acknowledge the unique nature and needs of the leagues and their athletes, we believe the leagues can learn from the other leagues’ policies. Leagues’ eligibility rules affect player health in two somewhat opposite directions: (1) by potentially forcing some players who might be ready to begin a career playing for the leagues to instead continue playing in amateur or lesser professional leagues with less (or no) compensation and at the risk of being injured; and, (2) by protecting other players from entering the leagues before they might be physically, intellectually, or emotionally ready. As will be shown, the NCAA’s Bylaws are an impor- tant factor in considering the eligibility rules and their effects on player health and thus must be included in this discussion. This issue too is discussed in our Recommendations. 206. \ Comparing Health-Related Policies & Practices in Sports In this Chapter we explain each of the leagues’ eligibility Nevertheless, the leagues’ eligibility rules have been gener- rules as well as the rules’ relationship to player health, if ally treated as not subject to antitrust scrutiny. Certain any. But first, we provide: (1) information on the eligibil- collective actions by the clubs are exempt from antitrust ity rules’ legal standing; (2) general information about laws under what is known as the non-statutory labor the leagues’ drafts that correspond to their eligibility exemption. -

Jan12it Is Superdraft Morning Feel the Excitement? the Hum Yeah This Chart Is Shaping up to Be an Interesting Ride Tomorrow

Jan12It is SuperDraft morning Feel the excitement? The hum Yeah this chart is shaping up to be an interesting ride tomorrow. Teams are within Baltimore as we talk getting geared up as this thing.This want be my final jeer chart as this SuperDraft. Today I?¡¥m going board and will be doing a two round version,nfl jersey wholesale. I know I?¡¥ve done now four of these things barely its something I enjoy a lot during the off season. It may be over kill aboard my part to do as much as I do merely with each passing week current information comes out alternatively I chat to alter folks approximately the alliance that aid form my opinions here so changes must be made.I?¡¥ve had a lot of fun this year with this chart probably as its allowed me to help out aboard other venues favor SBnation.com and more recently aboard FCDallas.com. I try my best what can I say,football jersey maker.Below is my two circular ridicule draft I?¡¥ll have adding comments under as I think there longing be some trades that jolt this plenary thing up. Should any colossal trade come down within the morning I?¡¥ll dispute it and what it longing mean as the blueprint at that point. For now the order is where it?¡¥s been by as a pair weeks immediately so as contentions sake, nothing is changing and this is how I see it playing out tomorrow.2011 WVH Mock Draft(* = Generation adidas)1. Vancouver Whitecaps ??Perry Kitchen*, M, AkronA present leader within the house is Kitchen. -

Major League Soccer As a Case Study in Complexity Theory

Florida State University Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Winter 2017 Article 1 Winter 2017 Major League Soccer as a Case Study in Complexity Theory Steven A. Bank UCLA School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Contracts Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven A. Bank, Major League Soccer as a Case Study in Complexity Theory, 44 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 385 (2018) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol44/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER AS A CASE STUDY IN COMPLEXITY THEORY STEVEN A. BANK* ABSTRACT Major League Soccer has long been criticized for its “Byzantine” roster rules and regu- lations, rivaled only by the Internal Revenue Code in its complexity. Is this criticism fair? By delving into complexity theory and the unique nature of the league, this Article argues that the traditional complaints may not apply in the context of the league’s roster rules. Effectively, critics are applying the standard used to evaluate the legal complexity found in rules such as statutes and regulations when the standard used to evaluate contractual complexity is more appropriate. Major League Soccer’s system of roster rules is the product of a contractual and organizational arrangement among the investor-operators. -

Jan12it Is Superdraft Morning Feel the Excitement? the Hum Yeah This Chart Is Shaping up to Be an Interesting Ride Tomorrow

Jan12It is SuperDraft morning Feel the excitement? The hum Yeah this chart is shaping up to be an interesting ride tomorrow. Teams are within Baltimore as we talk getting geared up as this thing.This want be my final jeer chart as this SuperDraft. Today I?¡¥m going board and will be doing a two round version,nfl jersey wholesale. I know I?¡¥ve done now four of these things barely its something I enjoy a lot during the off season. It may be over kill aboard my part to do as much as I do merely with each passing week current information comes out alternatively I chat to alter folks approximately the alliance that aid form my opinions here so changes must be made.I?¡¥ve had a lot of fun this year with this chart probably as its allowed me to help out aboard other venues favor SBnation.com and more recently aboard FCDallas.com. I try my best what can I say,football jersey maker.Below is my two circular ridicule draft I?¡¥ll have adding comments under as I think there longing be some trades that jolt this plenary thing up. Should any colossal trade come down within the morning I?¡¥ll dispute it and what it longing mean as the blueprint at that point. For now the order is where it?¡¥s been by as a pair weeks immediately so as contentions sake, nothing is changing and this is how I see it playing out tomorrow.2011 WVH Mock Draft(* = Generation adidas)1. Vancouver Whitecaps ??Perry Kitchen*, M, AkronA present leader within the house is Kitchen. -

Ezana Kahsay Daniel Strachan Ben Lundt Marcel Zajac David Egbo

Ben Lundt Ezana Kahsay David Egbo Skye Harter Daniel Strachan Marcel Zajac www.adidas.com TABLE OF CONTENTS TEAM INFORMATION MEET THE 2018 AKRON ZIPS MEDIA GUIDE 2018 Table of Contents ............................................................................................. 1 Meet the Zips ....................................................................................... 20-30 Quick Facts ...................................................................................................2 Directions to Campus ....................................................................................... 3 THIS IS AKRON SOCCER Athletics Communications ............................................................................... 3 This is Akron Soccer ............................................................................. 32-35 Quick Facts ....................................................................................................... 4 MLS Draft History ................................................................................. 36-38 2018 Schedule ................................................................................................. 5 Zips In The Pros ..........................................................................................39 Series Records vs. 2018 Opponents .............................................................6-7 Zips by Class ..............................................................................................40 Roster Information .......................................................................................... -

MLS Game Guide

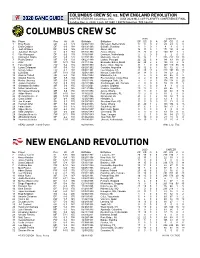

COLUMBUS CREW SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION MAPFRE STADIUM, Columbus, Ohio AUDI 2020 MLS CUP PLAYOFFS CONFERENCE FINAL Sunday, Dec. 6, 2020, 3 p.m. ET (ABC / ESPN Deportes, TVA Sports) COLUMBUS CREW SC 2020 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Eloy Room GK 6-3 179 02/06/1989 Nijmegen, Netherlands 17 17 0 0 29 29 0 0 2 Chris Cadden DF 6-0 168 09/19/1996 Bellshill, Scotland 8 3 0 1 8 3 0 1 3 Josh Williams DF 6-2 185 04/18/1988 Akron, OH 12 11 0 1 174 154 9 6 4 Jonathan Mensah DF 6-2 183 07/13/1990 Accra, Ghana 23 23 0 0 100 97 3 1 5 Vito Wormgoor DF 6-2 179 11/16/1988 Leersum, Netherlands 2 2 0 0 2 2 0 0 6 Darlington Nagbe MF 5-9 170 07/19/1990 Monrovia, Liberia 15 14 1 1 285 272 30 38 7 Pedro Santos MF 5-6 139 04/22/1988 Lisbon, Portugal 22 22 6 8 94 89 18 23 8 Artur MF 5-11 154 03/11/1996 Brumado, Bahia, Brazil 22 20 2 4 108 99 2 9 9 Fanendo Adi FW 6-4 185 10/10/1990 Benue State, Nigeria 11 1 0 0 149 110 55 14 10 Lucas Zelarayan MF 5-9 154 06/20/1992 Cordoba, Argentina 16 12 6 4 16 12 6 4 11 Gyasi Zardes FW 6-1 187 09/02/1991 Los Angeles, CA 21 20 12 4 213 197 78 23 12 Luis Diaz MF 5-11 159 12/06/1998 Nicoya, Costa Rica 21 14 0 3 34 23 2 7 13 Andrew Tarbell GK 6-3 194 10/07/1993 Mandeville, LA 7 6 0 0 48 46 0 0 14 Waylon Francis DF 5-9 160 09/20/1990 Puerto Limon, Costa Rica 4 2 0 0 115 98 0 19 16 Hector Jimenez MF 5-9 145 11/03/1988 Huntington Park, CA 8 4 0 1 176 118 6 25 17 Jordan Hamilton FW 6-0 185 03/17/1996 Scarborough, ON, Canada 2 0 0 0 59 28 11 3 18 Sebastian Berhalter MF 5-9 155 05/10/2001 London, England 9 4 0 0 9 4 0 0 19 Milton Valenzuela DF 5-6 145 08/13/1998 Rosario, Argentina 19 17 0 3 49 46 1 9 20 Emmanuel Boateng MF 5-6 150 01/17/1994 Accra, Ghana 10 3 0 1 121 68 9 14 21 Aidan Morris MF 5-10 158 11/16/2001 Fort Lauderdale, FL 10 2 0 0 10 2 0 0 22 Derrick Etienne Jr. -

U9/U10) Girls (U9/U10)

Introduction 2020 Always Moving Forward #WeAreVSA Contact Information Register for Tryouts - Here 2020 Jr Academy Director (U8-U10) - Benjy Slator - [email protected] Director of Coaching U11-U14 Girls - Tim Krout - [email protected] Director of Coaching U11-U14 Boys - Nick Foglesong - [email protected] Director of Coaching U15-U19 Girls - Bronson Gambale - [email protected] Director of Coaching U15-U19 Boys - Nick Rich - [email protected] Always Moving Forward #WeAreVSA VSA Who are We! Mission Statement: Our purpose is to be a community based soccer club that is committed to providing players of all levels and backgrounds the opportunity to play the beautiful game of soccer! Vision Statement: To build a pathway that provides a professionalized platform creating opportunities for all players in our club to succeed in life on and off the field Core Values: Community Collaboration Character Commitment Always Moving Forward #WeAreVSA VSA’s Four Pillars Who are We! Develop The Player: We will always put the player first and develop them in the 4 key components of the game (Technical, Tactical, Physical, Psychological). We will provide opportunities for all players to grow on the field. Develop The Person: We will always strive to look at the bigger picture and create young people who have characteristics and traits to succeed away from the soccer field. We will value hard work, humility, integrity, respect, responsibility, and a growth mindset above all else. Develop The Club: We will work together as coaches, players, and parents to create OUR CLUB that we can be proud to be part of. On and Off the field we will represent the club in the best possible way, striving to be people the local community can be proud of. -

Collective Bargaining Agreement

COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT Between MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER And MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER PLAYERS UNION February 1, 2015 – January 31, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLE 1 RECOGNITION AND UNION ACCESS ARTICLE 2 DEFINITIONS ARTICLE 3 DURATION OF AGREEMENT ARTICLE 4 UNION SECURITY AND CHECK-OFF ARTICLE 5 MANAGEMENT RIGHTS ARTICLE 6 NO-STRIKE, NO-LOCKOUT ARTICLE 7 NO DISCRIMINATION ARTICLE 8 PLAYER OBLIGATIONS ARTICLE 9 MEDICAL EXAMINATIONS; INJURY GUARANTEE ARTICLE 10 COMPENSATION, EXPENSES AND LEAGUE PLAYER EXPENDITURES ARTICLE 11 TRAVEL AND GAME TICKETS ARTICLE 12 DRUG TESTING ARTICLE 13 VACATION AND OTHER TIME OFF ARTICLE 14 ENTRY DRAFT, EXPANSION DRAFT AND ACADEMY PLAYER INFORMATION ARTICLE 15 LOANS AND TRANSFERS ARTICLE 16 PARTICIPATION IN HAZARDOUS ACTIVITIES AND OTHER SPORTS PROHIBITED ARTICLE 17 LEAGUE SCHEDULE AND OTHER GAME SCHEDULES ARTICLE 18 STANDARD PLAYER AGREEMENT ARTICLE 19 ROSTERS ARTICLE 20 DISCIPLINE; RULES AND REGULATIONS ARTICLE 21 GRIEVANCES AND ARBITRATIONS ARTICLE 22 INSURANCE COVERAGES ARTICLE 23 COMPETITION GUIDELINES ARTICLE 24 COMMITTEES; PLAYING CONDITIONS ARTICLE 25 ALL-STAR GAME; ALL-LEAGUE TEAMS ARTICLE 26 NOTICES ARTICLE 27 MISCELLANEOUS ARTICLE 28 GROUP LICENSING ARTICLE 29 PLAYER MOVEMENT RULES EXHIBIT 1 STANDARD PLAYER AGREEMENT EXHIBIT 2 AUTHORIZATION FOR RELEASE OF MEDICAL INFORMATION TO MLS AND MLS TEAMS EXHIBIT 3 CHECK-OFF AUTHORIZATION EXHIBIT 4 APPROVED HOTELS EXHIBIT 5 SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND BEHAVIORAL HEALTH PROGRAM AND POLICY EXHIBIT 6 COMPETITION GUIDELINES EXHIBIT 7 STANDARD MEDICAL EXAMINATION FORM EXHIBIT 8 INITIAL FITNESS DETERMINATION EXHIBIT 9 SECOND OPINION FITNESS DETERMINATION EXHIBIT 10 PHYSICIANS CONSULTATION FORM EXHIBIT 11 INDEPENDENT PHYSICIAN DETERMINATION FORM EXHIBIT 12 CONCUSSION PROTOCOL EXHIBIT 13 RE-ENTRY DRAFT RULES EXHIBIT 14 FREE AGENCY COMMITMENT FORM & SCHEDULE 3 THIS COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT made as of the 1st day of February, 2015, by and between MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER, L.L.C.