World Report on Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 Retina Gabriele K

299 12 Retina Gabriele K. Lang and Gerhard K. Lang 12.1 Basic Knowledge The retina is the innermost of three successive layers of the globe. It comprises two parts: ❖ A photoreceptive part (pars optica retinae), comprising the first nine of the 10 layers listed below. ❖ A nonreceptive part (pars caeca retinae) forming the epithelium of the cil- iary body and iris. The pars optica retinae merges with the pars ceca retinae at the ora serrata. Embryology: The retina develops from a diverticulum of the forebrain (proen- cephalon). Optic vesicles develop which then invaginate to form a double- walled bowl, the optic cup. The outer wall becomes the pigment epithelium, and the inner wall later differentiates into the nine layers of the retina. The retina remains linked to the forebrain throughout life through a structure known as the retinohypothalamic tract. Thickness of the retina (Fig. 12.1) Layers of the retina: Moving inward along the path of incident light, the individual layers of the retina are as follows (Fig. 12.2): 1. Inner limiting membrane (glial cell fibers separating the retina from the vitreous body). 2. Layer of optic nerve fibers (axons of the third neuron). 3. Layer of ganglion cells (cell nuclei of the multipolar ganglion cells of the third neuron; “data acquisition system”). 4. Inner plexiform layer (synapses between the axons of the second neuron and dendrites of the third neuron). 5. Inner nuclear layer (cell nuclei of the bipolar nerve cells of the second neuron, horizontal cells, and amacrine cells). 6. Outer plexiform layer (synapses between the axons of the first neuron and dendrites of the second neuron). -

Differentiate Red Eye Disorders

Introduction DIFFERENTIATE RED EYE DISORDERS • Needs immediate treatment • Needs treatment within a few days • Does not require treatment Introduction SUBJECTIVE EYE COMPLAINTS • Decreased vision • Pain • Redness Characterize the complaint through history and exam. Introduction TYPES OF RED EYE DISORDERS • Mechanical trauma • Chemical trauma • Inflammation/infection Introduction ETIOLOGIES OF RED EYE 1. Chemical injury 2. Angle-closure glaucoma 3. Ocular foreign body 4. Corneal abrasion 5. Uveitis 6. Conjunctivitis 7. Ocular surface disease 8. Subconjunctival hemorrhage Evaluation RED EYE: POSSIBLE CAUSES • Trauma • Chemicals • Infection • Allergy • Systemic conditions Evaluation RED EYE: CAUSE AND EFFECT Symptom Cause Itching Allergy Burning Lid disorders, dry eye Foreign body sensation Foreign body, corneal abrasion Localized lid tenderness Hordeolum, chalazion Evaluation RED EYE: CAUSE AND EFFECT (Continued) Symptom Cause Deep, intense pain Corneal abrasions, scleritis, iritis, acute glaucoma, sinusitis, etc. Photophobia Corneal abrasions, iritis, acute glaucoma Halo vision Corneal edema (acute glaucoma, uveitis) Evaluation Equipment needed to evaluate red eye Evaluation Refer red eye with vision loss to ophthalmologist for evaluation Evaluation RED EYE DISORDERS: AN ANATOMIC APPROACH • Face • Adnexa – Orbital area – Lids – Ocular movements • Globe – Conjunctiva, sclera – Anterior chamber (using slit lamp if possible) – Intraocular pressure Disorders of the Ocular Adnexa Disorders of the Ocular Adnexa Hordeolum Disorders of the Ocular -

Eyelid and Orbital Infections

27 Eyelid and Orbital Infections Ayub Hakim Department of Ophthalmology, Western Galilee - Nahariya Medical Center, Nahariya, Israel 1. Introduction The major infections of the ocular adnexal and orbital tissues are preseptal cellulitis and orbital cellulitis. They occur more frequently in children than in adults. In Schramm's series of 303 cases of orbital cellulitis, 68% of the patients were younger than 9 years old and only 17% were older than 15 years old. Orbital cellulitis is less common, but more serious than preseptal. Both conditions happen more commonly in the winter months when the incidence of paranasal sinus infections is increased. There are specific causes for each of these types of cellulitis, and each may be associated with serious complications, including vision loss, intracranial infection and death. Studies of orbital cellulitis and its complication report mortality in 1- 2% and vision loss in 3-11%. In contrast, mortality and vision loss are extremely rare in preseptal cellulitis. 1.1 Definitions Preseptal and orbital cellulites are the most common causes of acute orbital inflammation. Preseptal cellulitis is an infection of the soft tissue of the eyelids and periocular region that is localized anterior to the orbital septum outside the bony orbit. Orbital cellulitis ( 3.5 per 100,00 ) is an infection of the soft tissues of the orbit that is localized posterior to the orbital septum and involves the fat and muscles contained within the bony orbit. Both types are normally distinguished clinically by anatomic location. 1.2 Pathophysiology The soft tissues of the eyelids, adnexa and orbit are sterile. Infection usually originates from adjacent non-sterile sites but may also expand hematogenously from distant infected sites when septicemia occurs. -

Dialect and Local Media: Reproducing the Multi- Dialectal Hierarchical Space in Limburg (The Netherlands)

Dialect and local media: Reproducing the multi- dialectal hierarchical space in Limburg (the Netherlands) Leonie Cornips i, ii , Vincent de Rooij iii , Irene Stengs i ii and Lotte Thissen i Meertens Institute/The Royal Academy of Art and Sciences, Amsterdam; ii Maastricht University; iii University of Amsterdam The Netherlands 1 INTRODUCTION This chapter aims at contributing to an understanding of processes of language standardization by looking at a multidialectal public live performance, broadcast by local media in the Dutch province of Limburg. We will focus on this live perfor- mance, which involves a reading-aloud event of extracts from the fantasy book series Harry Potter . For this event, extracts were translated in written form into various Limburgian dialects. These translations obeyed the normative dialect or- thography acknowledged by the most important main actors in Limburg (see later). 2 The imposition of a normative spelling for dialects evidences processes of codifica- tion and implementation, two major stages in language standardization (cf. Deumert 2004, Haugen 2003, Milroy 2001). These ongoing processes in Limburg result in the standardization of multiple dialects that differ maximally from each other, espe- cially at the level of the lexicon. These processes also anchor the multiple dialects to place. Language standardization involves concern with form and function, and is based on as well as framed by ‘discursive projects’: Standardization is concerned with linguistic forms (corpus planning, i.e. selec- tion and codification) as well as the social and communicative functions of lan- guage (status planning, i.e. implementation and elaboration). In addition, stand- ard languages are also discursive projects, and standardization processes are typ- ically accompanied by the development of specific discourse practices. -

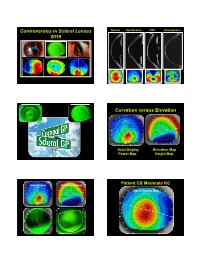

Controversies in Scleral Lenses 2019 Curvature Versus Elevation

Controversies in Scleral Lenses Normal Keratoconus PMD Keratoglobus 2019 Curvature versus Elevation Axial Display Elevation Map Power Map Height Map Axial Display Elevation Display Patient CB Moderate KC Axial Display Map +180um +180 +379 +379um Elevation Display -110 - 276 Elevation Map 655 Above the 290 microns Micron Sphere Height -276um Differential Depression Below the -110um Sphere N = 87 Patients 127 CL Fits Less than 350um Greater than 350um Patients with 350um or less of corneal elevation difference (along the greatest meridian of change) have an 88.2% chance of success with a corneal GP lens. The Re-Birth of Scleral Lenses Glass Scleral Lenses 1887 Molding Glass Scleral Lenses Average 8.5 High DK Scleral Materials Traditional Corneal / Scleral • Menicon Z Dk = 163 Shape • B & L, Boston XO2 DK = 141 • Contamac, Optimum Extreme DK = 125 • B & L, Boston XO DK = 100 • Paragon HDS 100 DK = 100 • Contamac, Optimum Extra DK = 100 • Lagado, Tyro -97 DK = 97 Scleral Shape Cone Angle Circa 1948 Klaus Pfortner New Understandings Argentina Scleral Lens Fitting Objectives Anatomy of a Scleral Lens 1. Central Vault Zone (250 to 400 microns) 2. Peripheral Lift Zone 4 3 2 1 2 3 4 3. Limbal Lift Zone 4. Scleral Landing Zone Ocular Surface Disease Scleral Lens Indications Scleral Irregular Astigmatism Lens • Keratoconus Indications • Pellucid Marginal Degeneration • Post Corneal Trauma • Post keratoplasty • Post K-Pro • Post Refractive Surgery RK, PRK and LASIK • Post HSV and HZV • Athletes • GP stability (rocking) issues Corneal Irregularity -

An Update on Progress and the Changing Epidemiology of Causes of Childhood Blindness Worldwide

Major Articles An update on progress and the changing epidemiology of causes of childhood blindness worldwide Lingkun Kong, MD, PhD,a Melinda Fry, MPH,b Mohannad Al-Samarraie, MD,a Clare Gilbert, MD, FRCOphth,c and Paul G. Steinkuller, MDa PURPOSE To summarize the available data on pediatric blinding disease worldwide and to present current information on childhood blindness in the United States. METHODS A systematic search of world literature published since 1999 was conducted. Data also were solicited from each state school for the blind in the United States. RESULTS In developing countries, 7% to 31% of childhood blindness and visual impairment is avoidable, 10% to 58% is treatable, and 3% to 28% is preventable. Corneal opacification is the leading cause of blindness in Africa, but the rate has decreased significantly from 56% in 1999 to 28% in 2012. There is no national registry of the blind in the United States, and most schools for the blind do not maintain data regarding the cause of blindness in their students. From those schools that do have such information, the top three causes are cortical visual impairment, optic nerve hypoplasia, and retinopathy of prematurity, which have not changed in past 10 years. CONCLUSIONS There are marked regional differences in the causes of blindness in children, apparently based on socioeconomic factors that limit prevention and treatment schemes. In the United States, the 3 leading causes of childhood blindness appear to be cortical visual impairment, optic nerve hypoplasia, and retinopathy of prematurity; a national registry of the blind would allow accumulation of more complete and reliable data for accurate determination of the prevalence of each. -

Onchocerciasis

11 ONCHOCERCIASIS ADRIAN HOPKINS AND BOAKYE A. BOATIN 11.1 INTRODUCTION the infection is actually much reduced and elimination of transmission in some areas has been achieved. Differences Onchocerciasis (or river blindness) is a parasitic disease in the vectors in different regions of Africa, and differences in cause by the filarial worm, Onchocerca volvulus. Man is the the parasite between its savannah and forest forms led to only known animal reservoir. The vector is a small black fly different presentations of the disease in different areas. of the Simulium species. The black fly breeds in well- It is probable that the disease in the Americas was brought oxygenated water and is therefore mostly associated with across from Africa by infected people during the slave trade rivers where there is fast-flowing water, broken up by catar- and found different Simulium flies, but ones still able to acts or vegetation. All populations are exposed if they live transmit the disease (3). Around 500,000 people were at risk near the breeding sites and the clinical signs of the disease in the Americas in 13 different foci, although the disease has are related to the amount of exposure and the length of time recently been eliminated from some of these foci, and there is the population is exposed. In areas of high prevalence first an ambitious target of eliminating the transmission of the signs are in the skin, with chronic itching leading to infection disease in the Americas by 2012. and chronic skin changes. Blindness begins slowly with Host factors may also play a major role in the severe skin increasingly impaired vision often leading to total loss of form of the disease called Sowda, which is found mostly in vision in young adults, in their early thirties, when they northern Sudan and in Yemen. -

MRSA Ophthalmic Infection, Part 2: Focus on Orbital Cellulitis

Clinical Update COMPREHENSIVE MRSA Ophthalmic Infection, Part 2: Focus on Orbital Cellulitis by gabrielle weiner, contributing writer interviewing preston h. blomquist, md, vikram d. durairaj, md, and david g. hwang, md rbital cellulitis is a poten- Acute MRSA Cellulitis tially sight- and life-threat- ening disease that tops the 1A 1B ophthalmology worry list. Add methicillin-resistant OStaphylococcus aureus (MRSA) to the mix of potential causative bacteria, and the level of concern rises even higher. MRSA has become a relatively prevalent cause of ophthalmic infec- tions; for example, one study showed that 89 percent of preseptal cellulitis S. aureus isolates are MRSA.1 And (1A) This 19-month-old boy presented with left periorbital edema and erythema preseptal cellulitis can rapidly develop five days after having been diagnosed in an ER with conjunctivitis and treated into the more worrisome condition of with oral and topical antibiotics. (1B) Axial CT image of the orbits with contrast orbital cellulitis if not treated promptly shows lacrimal gland abscess and globe displacement. and effectively. Moreover, the community-associ- and Hospital System in Dallas, 86 per- When to Suspect ated form of MRSA (CA-MRSA) now cent of those with preseptal cellulitis MRSA Orbital Cellulitis accounts for a larger proportion of and/or lid abscesses had CA-MRSA. Patients with orbital cellulitis com- ophthalmic cases than health care– These studies also found that preseptal monly complain of pain when moving associated MRSA (HA-MRSA). Thus, cellulitis was the most common oph- the eye, decreased vision, and limited many patients do not have the risk fac- thalmic MRSA presentation from 2000 eye movement. -

Expanding the Range of ZNF804A Variants Conferring Risk of Psychosis

Molecular Psychiatry (2011) 16, 59–66 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1359-4184/11 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Expanding the range of ZNF804A variants conferring risk of psychosis S Steinberg1, O Mors2, AD Børglum2,3, O Gustafsson1,4, T Werge5, PB Mortensen6, OA Andreassen4, E Sigurdsson7,8, TE Thorgeirsson1,YBo¨ttcher1, P Olason1, RA Ophoff9,10, S Cichon11, IH Gudjonsdottir1, OPH Pietila¨inen12,13, M Nyegaard3, A Tuulio-Henriksson14, A Ingason1, T Hansen5, L Athanasiu4, J Suvisaari14, J Lonnqvist14, T Paunio15, A Hartmann16,GJu¨rgens17, M Nordentoft18, D Hougaard19, B Norgaard-Pedersen20, R Breuer21, H-J Mo¨ller22, I Giegling16, B Glenthøj23, HB Rasmussen5, M Mattheisen10, I Bitter24,JMRe´thelyi24, T Sigmundsson7,8, R Fossdal1, U Thorsteinsdottir1,8, M Ruggeri25, S Tosato25, E Strengman9, GROUP37, LA Kiemeney26, I Melle4, S Djurovic27, L Abramova28, V Kaleda28, M Walshe29, E Bramon29, E Vassos29,30,TLi29,31, G Fraser32, N Walker33, T Toulopoulou29, J Yoon34, NB Freimer10, RM Cantor10,34, R Murray29, A Kong1, V Golimbet28,EGJo¨nsson35, L Terenius35, I Agartz35, H Petursson7,8,MMNo¨then36, M Rietschel21, L Peltonen12,13, D Rujescu16, DA Collier30,31, H Stefansson1, D St Clair32 and K Stefansson1,8 1deCODE genetics, Reykjavik, Iceland; 2Centre for Psychiatric Research, Aarhus University Hospital, Risskov, Denmark; 3Department of Human Genetics, Aarhus University, Arhus C, Denmark; 4Department of Psychiatry, Ulleva˚l University Hospital and Institute of Psychiatry, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway; 5Research -

Adult Patients Common Eye Infections

Common Eye Dermatitis: HZV and HSV Infections: Adult • Redness of periocular skin can be allergic Patients (if associated with prominent itching) or bacterial (if associated with open sores/wounds) Julie D. Meier, MD Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology • Both HZV and HSV can have devastating ocular sequelae if not treated promptly OSU Eye and Ear Institute General Categories of Herpes Zoster Eye Infections Ophthalmicus • Symptoms: Skin rash and pain, may be • Dermatitis of Lids (HZV, HSV) preceded by headache, fever, eye pain or • Cellulitis of Lids (pre- vs post-septal) blurred vision • Blepharitis • Signs: Vesicular skin rash involving CN V • Conjunctivitis distribution; Involvement of tip of nose can predict higher rate of ocular involvement • Keratitis 1 Herpes Zoster Herpes Simplex Virus Ophthalmicus • Symptoms: • Work-up 9 Duration of rash; Immunocompromised? 9 Red eye, pain, light sensitivity, skin rash 9 Complete ocular exam, including slit 9 Fever, flu-like symptoms lamp, IOP, and dilated exam • Signs: • Can have conjunctival or corneal involvement, elevated IOP, anterior 9 Skin rash: Clear vesicles on chamber inflammation, scleritis, or erythematous base that progress to even involvement of retina and optic crusting nerve. Herpes Zoster Herpes Simplex Virus Ophthalmicus • Work-up: • Treatment: 9 Previous episodes? 9 If present within 3 days of rash’s 9 Previous nasal, oral or genital sores? appearance: oral Acyclovir/ Valacyclovir 9 Recurrences can be triggered by fever, stress, trauma, UV exposure 9 Bacitracin ointment to skin lesions 9 External exam: More suggestive of HSV 9 Warm compresses if lesions centered around eye and no involvement of forehead/scalp 9 TOPICAL ANTIVIRALS (e.g. -

The Simplified Trachoma Grading System, Amended Anthony W Solomon,A Amir B Kello,B Mathieu Bangert,A Sheila K West,C Hugh R Taylor,D Rabebe Tekeraoie & Allen Fosterf

PolicyPolicy & practice & practice The simplified trachoma grading system, amended Anthony W Solomon,a Amir B Kello,b Mathieu Bangert,a Sheila K West,c Hugh R Taylor,d Rabebe Tekeraoie & Allen Fosterf Abstract A simplified grading system for trachoma was published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1987. Intended for use by non-specialist personnel working at community level, the system includes five signs, each of which can be present or absent in any eye: (i) trachomatous trichiasis; (ii) corneal opacity; (iii) trachomatous inflammation—follicular; (iv) trachomatous inflammation—intense; and (v) trachomatous scarring. Though neither perfectly sensitive nor perfectly specific for trachoma, these signs have been essential tools for identifying populations that need interventions to eliminate trachoma as a public health problem. In 2018, at WHO’s 4th global scientific meeting on trachoma, the definition of one of the signs, trachomatous trichiasis, was amended to exclude trichiasis that affects only the lower eyelid. This paper presents the amended system, updates its presentation, offers notes on its use and identifies areas of ongoing debate. Introduction (ii) corneal opacity; (iii) trachomatous inflammation—fol- licular; (iv) trachomatous inflammation—intense; and (v) tra- Trachoma is the most important infectious cause of blindness.1 chomatous scarring.19 Trachomatous inflammation—follicular Repeated conjunctival infection2 with particular strains of and trachomatous inflammation—intense are signs of active Chlamydia trachomatis3–5 -

Review Article the Status of Childhood Blindness And

[Downloaded free from http://www.meajo.org on Wednesday, January 07, 2015, IP: 41.235.88.16] || Click here to download free Android application for this journal Review Article The Status of Childhood Blindness and Functional Low Vision in the Eastern Mediterranean Region in 2012 Rajiv Khandekar, H. Kishore1, Rabiu M. Mansu2, Haroon Awan3 ABSTRACT Access this article online Website: Childhood blindness and visual impairment (CBVI) are major disabilities that compromise www.meajo.org the normal development of children. Health resources and practices to prevent CBVI are DOI: suboptimal in most countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR). We reviewed the 10.4103/0974-9233.142273 magnitude and the etiologies of childhood visual disabilities based on the estimates using Quick Response Code: socioeconomic proxy indicators such as gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and <5‑year mortality rates. The result of these findings will facilitate novel concepts in addressing and developing services to effectively reduce CBVI in this region. The current study determined the rates of bilateral blindness (defined as Best corrected visual acuity(BCVA)) less than 3/60 in the better eye or a visual field of 10° surrounding central fixation) and functional low vision (FLV) (visual impairment for which no treatment or refractive correction can improve the vision up to >6/18 in a better eye) in children <15 years old. We used the 2011 population projections, <5‑year mortality rates and GDP per capita of 23 countries (collectively grouped as EMR). Based on the GDP, we divided the countries into three groups; high, middle‑ and low‑income nations.