Right, Iraqi Army Officers and Ncos Receive Instruc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Army's M-4 Carbine: Background and Issues for Congress

The Army’s M-4 Carbine: Background and Issues for Congress Andrew Feickert Specialist in Military Ground Forces June 8, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS22888 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Army’s M-4 Carbine: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The M-4 carbine is the Army’s primary individual combat weapon for infantry units. While there have been concerns raised by some about the M-4’s reliability and lethality, some studies suggest that the M-4 is performing well and is viewed favorably by users. The Army is undertaking both the M4 Carbine Improvement Program and the Individual Carbine Competition, the former to identify ways to improve the current weapon, and the latter to conduct an open competition among small arms manufacturers for a follow-on weapon. An integrated product team comprising representatives from the Infantry Center; the Armament, Research, Development, and Engineering Center; the Program Executive Office Soldier; and each of the armed services will assess proposed improvements to the M4. The proposal for the industry-wide competition is currently before the Joint Requirements Oversight Council, and with the anticipated approval, solicitation for industry submissions could begin this fall. It is expected, however, that a selection for a follow-on weapon will not occur before FY2013, and that fielding of a new weapon would take an additional three to four years. This report will be updated as events warrant. Congressional Research Service The -

Department of Homeland Security Appropriations for Fiscal Year 2008

S. HRG. 110–36 DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2008 HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Department of Homeland Security Nondepartmental witnesses Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 33–920 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont TED STEVENS, Alaska TOM HARKIN, Iowa ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico HERB KOHL, Wisconsin CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATTY MURRAY, Washington MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota LARRY CRAIG, Idaho MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JACK REED, Rhode Island SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey WAYNE ALLARD, Colorado BEN NELSON, Nebraska LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director BRUCE EVANS, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland TED STEVENS, Alaska HERB KOHL, Wisconsin ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania PATTY MURRAY, Washington PETE V. -

2020 Training Cata

Training for the Military HIGH MOBILITY MULTIPURPOSE WHEELED VEHICLE 0665 FIELD SERVICE AND MILITARY TRAINING COURSE CATALOG Aftermarket Fulfillment and Training Center (AFTC) 5448 Dylan Drive, South Bend, Indiana 46628 Contents General Information 4 Student Registration 5 Payment Information 5 Advanced Mobility / Maintenance / BDAR 6 Field Maintenance Training 8 Sustainment Maintenance Training 10 4L80E Transmission Maintenance Training 12 “ Whether it is ‘training readiness,,’’ combat operations, Air Conditioning Systems Maintenance 14 oror domesticdomestic response to floods and other natural disasters, itit isis thethe soldiersoldier inin hishis oror herher HumveeHumvee thatthat AmeriAmerica sees Alternator / Starter / Electrical Systems Maintenance 16 ccoming to their aide.” —Major—Major GeneGenerral Courtneeyy CarCarrr,, IIndiana Naationaltional GuaGuarrd Diesel Fuel Injection Pump Maintenance Training 17 Visitor Information 18 2 3 2 Our program development experience has been Training gained throtugh the development of training on a myriad of equipment from the Humvee through Program various tactical bridging equipment, such as the Improved Ribbon Bridge, the Rapidly Emplaced Bridge Development System, all of the MK II series Bridge Erection Boats, as well as MRAP, LTAS Wrecker, water purification and AM General’s Military Training Department fuel distribution systems. is a TRADOC certified world leader in All of our training programs are written to comply with training program development. TRADOC Regulation 350-70. Our expert program writers and Military Training Department Staff graphic llustrators are highly trained, AM General’s Training Department provides and credentialed professionals. professional training programs at all military skill (echelon) levels for Army systems used in the military inventory. Our technical writers and program to develop professional programs of instruction (POI). -

Evaluation of Robotic Systems to Carry out Traverse Execution, Opportunistic Science, and Landing Site Evaluation Tasks

NASA/TM-2011-216157 Evaluation of Robotic Systems to Carry Out Traverse Execution, Opportunistic Science, and Landing Site Evaluation Tasks Stephen J. Hoffman, PhD1, Matthew J. Leonard2, Pascal Lee, PhD3 1Science Applications International Corporation, Houston 2NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston 3Mars Institute, SETI Institute, Moffett Field, California National Aeronautics and Space Administration Johnson Space Center Houston, TX 77058 September 2011 THE NASA STI PROGRAM OFFICE . IN PROFILE Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated to • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected the advancement of aeronautics and space papers from scientific and technical science. The NASA Scientific and Technical conferences, symposia, seminars, or other Information (STI) Program Office plays a key meetings sponsored or cosponsored by part in helping NASA maintain this important NASA. role. • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, technical, or historical information from The NASA STI Program Office is operated by NASA programs, projects, and mission, Langley Research Center, the lead center for often concerned with subjects having NASA’s scientific and technical information. substantial public interest. The NASA STI Program Office provides access to the NASA STI Database, the largest • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION English- collection of aeronautical and space science STI language translations of foreign scientific in the world. The Program Office is also and technical material pertinent to NASA’s NASA’s institutional mechanism for mission. disseminating the results of its research and Specialized services that complement the STI development activities. These results are Program Office’s diverse offerings include published by NASA in the NASA STI Report creating custom thesauri, building customized Series, which includes the following report databases, organizing and publishing research types: results . -

AM General V. Activision Blizzard

Case 1:17-cv-08644-GBD-JLC Document 218 Filed 03/31/20 Page 1 of 29 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORI( -- -- ----- -- -- ------------------------- --x AM GENERAL LLC, Plaintiff, MEMORANDUM DECISION -against- AND ORDER ACTIVISION BLIZZARD, INC., ACTIVISION 17 Civ. 8644 (GBD) PUBLISHING, INC., and MAJOR LEAGUE GAMING CORP., Defendants. --------- -- --- -- --------- -- -- -- ---- -- - --x GEORGE B. DANIELS, United States District Judge: Plaintiff AM General LLC ("AMG") brings this action against Defendants Activision Blizzard, Inc. and Activision Publishing, Inc. (collectively, "Activision") and Major League Gaming Corp. ("MLG") for trademark infringement, trade dress infringement, unfair competition, false designation of origin, false advertising, and dilution under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1114, 1125, and 1125(c), respectively. (Compl., ECF No. 1, ~~ 82-147.) AMG also raises pendant New York state law claims for trademark infringement, unfair competition, false designation of origin, trade dress infringement, false advertising, and dilution. (Jd. ~~ 148-81.) On May 31, 2019, Defendants moved for summaty judgment on all of AMG's claims pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56. (Defs. Activision and MLG's Notice of Mot. for Summ. J., ECF No. 131.) On the same day, Plaintiff moved for partial summaty judgment on Defendants' laches claim pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56(a). (PI. AMG's Notice of Mot. for Partial Summ. J., ECF No. 138.) Subsequently, Defendants filed a motion to strike (1) certain portions of Plaintiffs Rule 56.1 statement of material facts and (2) the "experiment" contained in the rebuttal report of Plaintiff s expeli, Dr. Y oran Wind ("MTS I"). -

Federal Court Between

Court File No. T-735-20 FEDERAL COURT BETWEEN: CHRISTINE GENEROUX JOHN PEROCCHIO, and VINCENT R. R. PEROCCHIO Applicants and ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA Respondent AFFIDAVIT OF MURRAY SMITH Table of Contents A. Background 3 B. The Firearms Reference Table 5 The Canadian Firearms Program (CFP): 5 The Specialized Firearms Support Services (SFSS): 5 The Firearms Reference Table (FRT): 5 Updates to the FRT in light of the Regulation 6 Notice to the public about the Regulation 7 C. Variants 8 The Nine Families 8 Variants 9 D. Bore diameter and muzzle energy limit 12 Measurement of bore diameter: 12 The parts of a firearm 13 The measurement of bore diameter for shotguns 15 The measurement of bore diameter for rifles 19 Muzzle Energy 21 E. Non-prohibited firearms currently available for hunting and shooting 25 Hunting 25 Sport shooting 27 F. Examples of firearms used in mass shooting events in Canada that are prohibited by the Regulation 29 2 I, Murray Smith, of Ottawa, Ontario, do affirm THAT: A. Background 1. I am a forensic scientist with 42 years of experience in relation to firearms. 2. I was employed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (“RCMP”) during the period of 1977 to 2020. I held many positions during that time, including the following: a. from 1989 to 2002,1 held the position of Chief Scientist responsible for the technical policy and quality assurance of the RCMP forensic firearms service, and the provision of technical advice to the government and police policy centres on firearms and other weapons; and b. -

Small Arms-Individual Weapons

290 Small Arms–Individual Weapons INVESTMENT COMPONENT Modernization thousand M14 EBRs were assembled be mounted on the shotgun. The bolt • 1QFY09: Materiel release and full- at TACOM Lifecycle Management handle is mountable on either side for rate production decision Recapitalization Command at Rock Island Arsenal in ambidextrous handling. • 3QFY09: First unit equipped response to Operational Need Statements M26 Modular Accessory Shotgun Maintenance requesting a longer range capability. The MASS enables Soldiers to transition System: The upgraded weapons are currently in between lethal and less-than-lethal fires • 4QFY09: Limited user test and MISSION service with select Army units. and adds the capability of a separate evaluation with MP units Enables warfighters and small units to shotgun without carrying a second • 2QFY10: Low-rate initial production engage targets with lethal fire to defeat The M320 Grenade Launcher is the weapon. Additional features include a approved or deter adversaries. replacement to all M203 series grenade box magazine, flip-up sights, and an • 4QFY10: First article testing launchers on M16 Rifles and M4 extendable stand-off device for door complete DESCRIPTION Carbines. A modular system, it attaches breaching. The M4 Carbine replaces the M16 series under the barrel of the rifle or carbine PROJECTED ACTIVITIES Rifles in all Brigade Combat Teams, and can convert to a stand-alone weapon. SYSTEM INTERDEPENDENCIES M4 Carbine: Division Headquarters, and other The M320 improves on current grenade None • Continue: M4 production, deliveries, selected units. It is 1.4 pounds lighter launchers with an integral day/night and fielding and more portable than the M16 series of sighting system and improved safety PROGRAM STATUS M14 EBR: rifles. -

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya About MERI The Middle East Research Institute engages in policy issues contributing to the process of state building and democratisation in the Middle East. Through independent analysis and policy debates, our research aims to promote and develop good governance, human rights, rule of law and social and economic prosperity in the region. It was established in 2014 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Middle East Research Institute 1186 Dream City Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq T: +964 (0)662649690 E: [email protected] www.meri-k.org NGO registration number. K843 © Middle East Research Institute, 2017 The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of MERI, the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publisher. The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict MERI Policy Paper Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya October 2017 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................4 2. “Reconciliation” after genocide .........................................................................................................5 -

Fighting-For-Kurdistan.Pdf

Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq CRU Report Feike Fliervoet Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq Feike Fliervoet CRU Report March 2018 March 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: Peshmerga, Kurdish Army © Flickr / Kurdishstruggle Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the author Feike Fliervoet is a Visiting Research Fellow at Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit where she contributes to the Levant research programme, a three year long project that seeks to identify the origins and functions of hybrid security arrangements and their influence on state performance and development. -

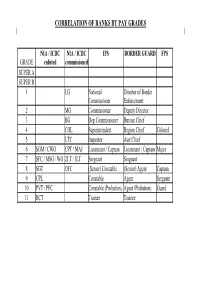

Security Salary Matrix (.Pdf)

CORRELATION OF RANKS BY PAY GRADES NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER GUARDFPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B 1 LG National Director of Border Commissioner Enforcement 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 3 BG Dep Commissioner Bureau Chief 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 6 SGM / CWO CPT / MAJ Lieutenant / Captain Lieutenant / Captain Major 7 SFC / MSG / WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 8 SGT OFC (Senior) Constable (Senior) Agent Captain 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 11 RCT Trainee Trainee COMPARISON OF RANKS (SHOWING INITIAL STEP INCREMENT) NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER FPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B National Dir of Border 1 LG Commissioner Enforcement 1 1 1 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 1 1 1 Dep 3 BG Commissioner Bureau Chief 1 1 1 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 1 1 1 1 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 1 1 1 6 SGM / CWO CAPT/MAJ Lieut / Captain Lieut / Captain Major 1 2 1 6 1 6 1 6 1 7 SFC/MSG/WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 4 7 8 6 7 6 6 8 SGT OFC (Snr) Constable (Snr) Agent Captain 6 8 6 6 1 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 7 5 5 1 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 4 8 4 4 1 11 Recruit Trainee Trainee 1 4 4 ENTRY LEVEL SALARIES FOR NEW IRAQI ARMY / IRAQI CIVIL DEFENCE CORPS STEPS- SALARIES LISTED IN NEW IRAQI DINAR Grade Enlisted Commission 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 LG 740,000 760,000 780,000 80,0000 820,000 840,000 860,000 880,000 2 MG 574,000 589,000 605,000 620,000 636,000 651,000 -

PM Crew Served Weapons Overview Small Arms Symposium & Exhibition

TheThe Soldier:Soldier: America’sAmerica’s MostMost DeployedDeployed CombatCombat SystemSystem PM Crew Served Weapons Overview for the Small Arms Symposium & Exhibition National Defense Industrial Association 16-19 May 2006 BG James R. Moran COL Carl A. Lipsit Mr. Peter Errante Program Executive Officer Soldier PM Soldier Weapons Deputy PM Crew Served Weapons Crew Served Weapons 2 PM Soldier Weapons Programs List DEVELOPMENT WEAPONS PROCUREMENT Objective Individual Combat Weapon (OICW) 37. M101, CROWS, Remote Mount 1. OICW Increment I 38. M151E1 & M151E2 Protector Remote Wpn System (RWS) 2. OICW Increment II - XM25 Air Burst Weapon 39. MK19 Advanced Crew Served Weapons (ACSW) 40. Mod Kit 3. Advanced Crew Served Weapon (ACSW) Programs 41. Lightweight Adjustable Sight Bracket 42. Tactical Engagement Simulator (TES) SOLDIER ENHANCEMENT PROGRAMS 43. M107 Semi Automatic Long Range Sniper Rifle 4. XM26 - 12 Gauge Modular Accessory Shotgun System 44. M240B, 7.62mm Medium MG (MASS) 45. M240B Collapsible Buttstock 5. Joint Combat Pistol 46. M192, Light Weight Ground Mount For MG 6. Family of Small Arms Suppressors 47. Improved Bipod 7. M68 Close Combat Optics (Dual Source Qualification) 48. Improved Flash Suppressor 8. XM1068, 12 Gauge Non-Lethal Extended Range Round 49. Combat Ammunition Pack 9. XM1022, Sniper Ammunition for M107 50. M240B Short Barrel 10. XM110 - 7.62 Semi-Automatic Sniper System (SASS) 51. M240B Improved Buttstock 11. Close Quarters Battle Kit 52. Sling Assembly for the M240B 12. XM1041/XM1042/XM1071 - Close Combat Mission 53. Short Barrel Capability Kit 54. M249, 5.56mm Squad Automatic Weapon 13. Advanced Sniper Accessory Kit (ASAK) 55. M192, Lightweight Ground Mount For MG 14. -

U.S. Army Board Study Guide Version 5.3 – 02 June, 2008

U.S. Army Board Study Guide Version 5.3 – 02 June, 2008 Prepared by ArmyStudyGuide.com "Soldiers helping Soldiers since 1999" Check for updates at: http://www.ArmyStudyGuide.com Sponsored by: Your Future. Your Terms. You’ve served your country, now let DeVry University serve you. Whether you want to build off of the skills you honed in the military, or launch a new career completely, DeVry’s accelerated, year-round programs can help you make school a reality. Flexible, online programs plus more than 80 campus locations nationwide make studying more manageable, even while you serve. You may even be eligible for tuition assistance or other military benefits. Learn more today. Degree Programs Accounting, Business Administration Computer Information Systems Electronics Engineering Technology Plus Many More... Visit www.DeVry.edu today! Or call 877-496-9050 *DeVry University is accredited by The Higher Learning Commission of the North Central Association, www.ncahlc.org. Keller Graduate School of Management is included in this accreditation. Program availability varies by location Financial Assistance is available to those who qualify. In New York, DeVry University and its Keller Graduate School of Management operate as DeVry College of New York © 2008 DeVry University. All rights reserved U.S. Army Board Study Guide Table of Contents Army Programs ............................................................................................................................................. 5 ASAP - Army Substance Abuse Program...............................................................................................