Full Text in Pdf Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sapo National Park in West Africa: Liberia's First

362 Environmental Conservation Sapo National Park in West Africa: Liberia's First Sapo National Park is the first to be established of three proposed national parks and four nature reserves that were selected in late 1978 and early 1979 with the assistance of IUCN and the World Wildlife Fund. The Park is situated in southeastern Liberia and covers a total land area of 505 sq. miles (1,308 sq. km) of primary lowland rain-forest (Fig. 1). Sapo is 440 miles (704 km) by road from Monrovia, Liberia's capital city. There are regular local air services from Monrovia to Greenville (lying to the South-West of the Park) and Zwedru to its North. The new National Park supports many species of large and small mammals which are also distributed through- out the forested regions of the country. Among these are FIG. 1. Aerial view of Sapo National Park, Liberia, showing the seven species of duikers including rare ones such as undulating terrain and covering of rain-forest. Jentink's Duiker {Cephalophus jentinki), Ogilby's Duiker (C. ogilbyi), and the Zebra Duiker (C. zebra). Other others are ex-hunters or farmers who are well-acquainted mammals include the Bongo (Boccerns euryceros), Pygmy with the forest environment in that part of the country. Hippopotamus {Choeropsis liberiensis), Forest Buffalo The official establishment of Sapo National Park in {Syncerus coffer nanus), and the Forest Elephant May 1983 was a major breakthrough for wildlife {Loxodonta africana cyclotis). More than ten species of conservation practices in Liberia, and its development primates are found in Sapo: these include Chimpanzee may stimulate the creation of the other national parks and {Pan troglodytes), Western Black and White Colobus nature reserves. -

Radar.Brookes.Ac.Uk/Radar/Items/C664d3c7-1663-4D34-Aed5-E3e070598081/1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR RADAR Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository Pozzi, L, Nekaris, K, Perkin, A, Bearder, S, Pimley, E, Schulze, H, Streicher, U, Nadler, T, Kitchener, A, Zischler, H, Zinner, D and Roos, C Remarkable Ancient Divergences Amongst Neglected Lorisiform Primates Pozzi, L, Nekaris, K, Perkin, A, Bearder, S, Pimley, E, Schulze, H, Streicher, U, Nadler, T, Kitchener, A, Zischler, H, Zinner, D and Roos, C (2015) Remarkable Ancient Divergences Amongst Neglected Lorisiform Primates. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 175 (3). pp. 661-674. doi: 10.1111/zoj.12286 This version is available: https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/c664d3c7-1663-4d34-aed5-e3e070598081/1/ Available on RADAR: August 2016 Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the published version of the journal article. WWW.BROOKES.AC.UK/GO/RADAR bs_bs_banner Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2015, 175, 661–674. With 3 figures Remarkable ancient divergences amongst neglected lorisiform primates LUCA -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 09:14:05PM Via Free Access 218 Rode-Margono & Nekaris – Impact of Climate and Moonlight on Javan Slow Lorises

Contributions to Zoology, 83 (4) 217-225 (2014) Impact of climate and moonlight on a venomous mammal, the Javan slow loris (Nycticebus javanicus Geoffroy, 1812) Eva Johanna Rode-Margono1, K. Anne-Isola Nekaris1, 2 1 Oxford Brookes University, Gipsy Lane, Headington, Oxford OX3 0BP, UK 2 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: activity, environmental factors, humidity, lunarphobia, moon, predation, temperature Abstract Introduction Predation pressure, food availability, and activity may be af- To secure maintenance, survival and reproduction, fected by level of moonlight and climatic conditions. While many animals adapt their behaviour to various factors, such nocturnal mammals reduce activity at high lunar illumination to avoid predators (lunarphobia), most visually-oriented nocturnal as climate, availability of resources, competition, preda- primates and birds increase activity in bright nights (lunarphilia) tion, luminosity, habitat fragmentation, and anthropo- to improve foraging efficiency. Similarly, weather conditions may genic disturbance (Kappeler and Erkert, 2003; Beier influence activity level and foraging ability. We examined the 2006; Donati and Borgognini-Tarli, 2006). According response of Javan slow lorises (Nycticebus javanicus Geoffroy, to optimal foraging theory, animal behaviour can be seen 1812) to moonlight and temperature. We radio-tracked 12 animals as a trade-off between the risk of being preyed upon in West Java, Indonesia, over 1.5 years, resulting in over 600 hours direct observations. We collected behavioural and environmen- and the fitness gained from foraging (Charnov, 1976). tal data including lunar illumination, number of human observ- Perceived predation risk assessed through indirect cues ers, and climatic factors, and 185 camera trap nights on potential that correlate with the probability of encountering a predators. -

An Act for the Extension of Ti1e Sapo National Park

AN ACT FOR THE EXTENSION OF TI1E SAPO NATIONAL PARK APPROVED: OCTOBER 10,2003 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS ,OCTOBER 24, 2003 MONROVIA, LIBERIA AN ACT FOR THE EXTENSION OF THE SAPO NATIONAL PARK WHEREAS, it has been the policy of the Government of the Republic of Liberia to adopt such measures as deemed conducive in the interest of the State; and WHEREAS, our forests are among our greatest natural resources and may be made to contribute greatly to the socio economic, scientific and educational welfare of Liberia by being managed in such a manner as to ensure their sustainable use; and WHEREAS, the protection, conservation and sustainable utilization of these resources must be carried out promptly, efficiently and wisely, under such conditions as will ensure continued benefits to present and future generations of Liberia; and WHEREAS, 'Sapo National Park, establlsheo in 1983, is recognized as being at the core of an immense forests block of the Upper Guinea Forest Ecosystem that is important to the conservation of the biodiversity of Liberia and of West Africa as a whole; and WHEREAS, it has been determined by socio-economic and biological surveys and with consultation of the local community that the integrity of the Sapo National Park consisting of 323,075 acres requires that its boundaries be extended; NOW THEREFORE it is enacted by the Senate and the House at Representatives ofthe Republic ofUberia, in Legislative Assembled: Section 1.1 Title: An Act for the Extension of the Sapo National Park to Embrace 445,677 Acres of Forest Land Section 1. -

Hunting Behavior of Wild Chimpanzees in the Taï National Park

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 78547-573 (1989) Hunting Behavior of Wild Chimpanzees in the Tai’ National Park CHRISTOPHE BOESCH AND HEDWIGE BOESCH Department of Ethology and Wildlife Research, University of Zurich, CH-8057 Zurich, Switzerland KEY WORDS Cooperation, Sharing, Traditions ABSTRACT Hunting is often considered one of the major behaviors that shaped early hominids’ evolution, along with the shift toward a drier and more open habitat. We suggest that a precise comparison of the hunting behavior of a species closely related to man might help us understand which aspects of hunting could be affected by environmental conditions. The hunting behavior of wild chimpanzees is discussed, and new observations on a population living in the tropical rain forest of the TaY National Park, Ivory Coast, are presented. Some of the forest chimpanzees’ hunting performances are similar to those of savanna-woodlands populations; others are different. Forest chimpanzees have a more specialized prey image, intentionally search for more adult prey, and hunt in larger groups and with a more elaborate cooperative level than sa- vanna-woodlands chimpanzees. In addition, forest chimpanzees tend to share meat more actively and more frequently. These findings are related to some theories on aspects of hunting behavior in early hominids and discussed in order to understand some factors influencing the hunting behavior of wild chimpanzees. Finally, the hunting behavior of primates is compared with that of social carnivores. Hunting is generally -

Panthera Pardus) Range Countries

Profiles for Leopard (Panthera pardus) Range Countries Supplemental Document 1 to Jacobson et al. 2016 Profiles for Leopard Range Countries TABLE OF CONTENTS African Leopard (Panthera pardus pardus)...................................................... 4 North Africa .................................................................................................. 5 West Africa ................................................................................................... 6 Central Africa ............................................................................................. 15 East Africa .................................................................................................. 20 Southern Africa ........................................................................................... 26 Arabian Leopard (P. p. nimr) ......................................................................... 36 Persian Leopard (P. p. saxicolor) ................................................................... 42 Indian Leopard (P. p. fusca) ........................................................................... 53 Sri Lankan Leopard (P. p. kotiya) ................................................................... 58 Indochinese Leopard (P. p. delacouri) .......................................................... 60 North Chinese Leopard (P. p. japonensis) ..................................................... 65 Amur Leopard (P. p. orientalis) ..................................................................... 67 Javan Leopard -

Rajan Amin Zsl Camera Trapping

ZSL CAMERA TRAP ANALYSIS PACKAGE RAJAN AMIN ZSL CAMERA TRAPPING • BIODIVERSITY SURVEY AND MONITORING • RESEARCH IN ANALYTICAL METHODS • TRAINING IN FIELD IMPLEMENTATION • ANALYTICAL PROCESSING TOOLS • RANGE OF SPECIES, HABITATS & CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES ZSL CAMERA TRAPPING • ALGERIA • MONGOLIA • KENYA • NEPAL • TANZANIA • THAILAND • LIBERIA • INDONESIA • GUINEA • RUSSIA • NIGER • SAUDI ARABIA • Et al. KENYA: ADERS’ DUIKER COASTAL FOREST • Critically endangered species • Poor knowledge of wildlife in the area MONGOLIA: GOBI BEAR DESERT • Highly threatened flagship species • Very little known about it NEPAL: TIGER GRASSLAND AND FORESTS • National level surveys, highly threatened flagship species SAUDI ARABIA: ARABIAN GAZELLE • Highly threatened species • Monitoring reintroduction efforts ZSL CAMERA TRAP ANALYSIS PACKAGE OCCUPANCY SPECIES RICHNESS TRAPPING RATE & LOCATION ACTIVITY Why is an analysis tool needed? MANUAL PROCESSING: MULTI-SPECIES STUDIES 45 cameras x 150days x c.30sp 30 25 20 15 Observed Discovery Rate N SpeciesN Minus 1 sd 10 Plus 1 sd Diversity estimate (Jacknife 1) 5 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Days of Camera trapping WA Large-spotted Genet Bourlon's Genet 7 8 6 7 5 6 5 4 4 3 Events Events 3 2 2 1 1 0 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 Hr. Hr. MANUAL PROCESSING: MULTI-SPECIES STUDIES 80 Camera sites x 100 days x c.30sp Amin, R., Andanje, S., Ogwonka, B., Ali A. H., Bowkett, A., Omar, M. & Wacher, T. 2014 The northern coast forests of Kenya are nationally and globally important for the conservation of Aders’ duiker Cephalophus adersi and other antelope species. -

Infant Development in the Slender Loris (Loris Lydekkerianus Lydekkerianus)

RESEARCH ARTICLES Infant development in the slender loris (Loris lydekkerianus lydekkerianus) Sindhu Radhakrishna1,* and Mewa Singh Department of Psychology, University of Mysore, Mysore 570 006, India 1Present address: National Institute of Advanced Studies, Indian Institute of Science Campus, Bangalore 560 012, India lorises and bushbabies)1, the lorids (angwantibos, pottos In this article we present data on infant development in wild slender loris, a nocturnal primate species. The and lorises) typically have lower developmental and repro- ductive rates in comparison to similar-sized galagos (bush- behavioural ecology of the grey slender loris Loris lyde- 2–4 kkerianus lydekkerianus, a nocturnal strepsirrhine, babies) . Litter size in lorids and galagos appears to be was studied for 21 months (October 1997–June 1999) linked to the stability of the habitat more than body size: in a scrub jungle in Dindigul, south India. A total of species occupying harsher environments tend to have 22,834 scans were collected during 2656 h of observa- higher reproductive rates3,5. Strepsirrhine neonates are tion on identified and unidentified lorises using in- carried for short periods following birth and mode of stantaneous point and ad libitum sampling methods. infant transport can be oral (Galagos bushbabies, Cheiro- Developmental schedules were observed for twelve in- galeus dwarf lemurs, Microcebus mouse lemurs) or the dividuals born during the course of the study period. abdominal fur of the mother (Loris slender loris)3,6,7. In- A greater number of twin births were observed than fant parking is typical of the Loriformes, wherein infants singleton births and more isosexuals than heterosexu- als. -

Table 14 B: Threat Due to Predation, Poaching and Similar Causes 1, 2,

Table 14 b: Threat due to predation, poaching and similar causes 1, 2, ... : source, author quoted. (Sub-)Species, form, Natural causes of losses such Recorded causes of threat caused by human activities such as poaching, trade subpopulation as predation (Threat due to habitat destruction see table 14 c) Lorises, pottos During a survey in Sri Lanka in Contact with uninsulated power lines is may be fatal for the slowly climbing lorises and pottos who are specialized on bridging over substrate gaps with their long 2001, presence of Loris seemed limbs. Death of lorises on power lines are reported from Sri Lanka, India and Malaysia (see also below) 207, 66, 211. From Africa, no data concerning pottos or in general to be negatively associated with angwantibos are available, but the problem with power lines apparently also exists, regular deaths of colobus monkeys have been reported 208, regarded as the main potential predators and cause of colobus monkey mortalities in Diani; other monkeys are also affected. The Kenya Power and Lighting Company engineers spent a day with coworkers of competitors 211. the Colobus Trust exploring ways to solve the problem. Victims of electrocution showed amputated limbs 209. Asian lorises L I Slender lorises, genus In India, in 1981 "lorises belong to India's most endangered species" 116. There are very few Slender lorises left in the wild 121. Slender lorises belong to the Loris animals found in illegal ownership (pets) 110. It was also a popular cage animal. Twenty-five years ago, one could buy a loris for a few rupees in Chennai Moore market or Bangalore Russel market. -

Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK

Technical Assistance Report Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK - Sapo National Park -Vision Statement By the year 2010, a fully restored biodiversity, and well-maintained, properly managed Sapo National Park, with increased public understanding and acceptance, and improved quality of life in communities surrounding the Park. A Cooperative Accomplishment of USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon- USDA Forest Service May 29, 2005 to June 17, 2005 - 1 - USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Protected Area Development Management Plan Development Technical Assistance Report Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon 17 June 2005 Goal Provide support to the FDA, CI and FFI to review and update the Sapo NP management plan, establish a management plan template, develop a program of activities for implementing the plan, and train FDA staff in developing future management plans. Summary Week 1 – Arrived in Monrovia on 29 May and met with Forestry Development Authority (FDA) staff and our two counterpart hosts, Theo Freeman and Morris Kamara, heads of the Wildlife Conservation and Protected Area Management and Protected Area Management respectively. We decided to concentrate on the immediate implementation needs for Sapo NP rather than a revision of existing management plan. The four of us, along with Tyler Christie of Conservation International (CI), worked in the CI office on the following topics: FDA Immediate -

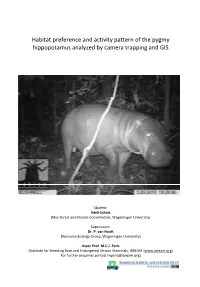

Habitat Preference and Activity Pattern of the Pygmy Hippopotamus Analyzed by Camera Trapping and GIS

Habitat preference and activity pattern of the pygmy hippopotamus analyzed by camera trapping and GIS Student: Henk Eshuis (Msc Forest and Nature Conservation, Wageningen University) Supervisors: Dr. P. van Hooft (Resource Ecology Group, Wageningen University) Assoc Prof. M.C.J. Paris (Institute for Breeding Rare and Endangered African Mammals; IBREAM (www.ibream.org) For further enquiries contact [email protected]) Habitat preference and activity pattern of the pygmy hippopotamus analyzed by camera trapping and GIS Submitted: 03-11-2011 REG-80439 Student: Henk Eshuis (Msc Forest and Nature Conservation, Wageningen University) 850406229010 Supervisors: Dr. P. van Hooft (Resource Ecology Group, Wageningen University) Assoc prof. M.C.J. Paris (Institute for Breeding Rare and Endangered African Mammals; IBREAM, www.ibream.org) Abstract The pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis) is an elusive and endangered species that only occurs in West Africa. Not much is known about the habitat preference and activity pattern of this species. We performed a camera trapping study and collected locations of pygmy hippo tracks in Taï National Park, Ivory Coast, to determine this more in detail. In total 1785 trap nights were performed with thirteen recordings of pygmy hippo on ten locations. In total 159 signs of pygmy hippo were found. We analyzed the habitat preferences with a normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) from satellite images, distance to rivers and clustering using GIS. The NDVI indicates that pygmy hippos are mostly found in a wetter vegetation type. Most tracks we found in the first 250 m from a river and the tracks show significant clustering. These observations indicate that the pygmy hippopotamus prefers relatively wet vegetation close to rivers. -

Primate Conservation

Primate Conservation Global evidence for the effects of interventions Jessica Junker, Hjalmar S. Kühl, Lisa Orth, Rebecca K. Smith, Silviu O. Petrovan and William J. Sutherland Synopses of Conservation Evidence ii © 2017 William J. Sutherland This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Junker, J., Kühl, H.S., Orth, L., Smith, R.K., Petrovan, S.O. and Sutherland, W.J. (2017) Primate conservation: Global evidence for the effects of interventions. University of Cambridge, UK Further details about CC BY licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Cover image: Martha Robbins/MPI-EVAN Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda Digital material and resources associated with this synopsis are available at https://www.conservationevidence.com/ iii Contents About this book ............................................................................................................................. xiii 1. Threat: Residential and commercial development ............................ 1 Key messages ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1. Remove and relocate ‘problem’