Historic England Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spurn National Nature Reserve Wildfowl to the Estuary, and the Opportunity to See Birds of Prey

Yorkshire Wildlife Trust It is thanks to the fantastic In the autumn be is a local charity working support of our members, on the look out for to protect and conserve volunteers and supporters marine mammals Look out for Yorkshire’s wild places and that we are able to continue nesting ringed including harbour wildlife for all to enjoy. with this work. porpoises, grey plovers in and common seals. the spring; be We care for over 95 nature Why not join us? careful not to reserves throughout the Joining is easy! For a small amount disturb them county and run loads of a month you can support Yorkshire’s though as this events so that everyone wildlife and wild places and get SPURN is an important can get out and experience involved with loads of fantastic breeding wild Yorkshire for activities and events. Visit www.ywt.org.uk or call 01904 659570. habitat for themselves. this vulnerable National species. Get in touch Ringed plover Call: 01964 650533 Nature Reserve Grey seal Email: [email protected] Find us: HU12 0UB WHAT TO LOOK OUT FOR Sea holly Grid reference: TA 410159 Winter brings large numbers of waders and at Spurn National Nature Reserve wildfowl to the estuary, and the opportunity to see birds of prey. A 1 6 Hornsea 5 North Sea B Hull 12 4 Hedon 2 Withernsea A 103 Hodgson’s 3 Fields Easington B H Patrington 14 u 45 m Welwick Red-veined darter Brent goose b Red admiral er Welwick Kilnsea Spurn Point N Saltmarsh Wetlands Kilnsea Summer is a Spurn good time to look for dragonflies, Grimsby damselflies and butterflies – keep an eye open Opening times for butterflies Nature Reserve: 7 day a week, road subject to like ringlets, closure – check website for latest news. -

Yorkshire Painted and Described

Yorkshire Painted And Described Gordon Home Project Gutenberg's Yorkshire Painted And Described, by Gordon Home This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Yorkshire Painted And Described Author: Gordon Home Release Date: August 13, 2004 [EBook #9973] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK YORKSHIRE PAINTED AND DESCRIBED *** Produced by Ted Garvin, Michael Lockey and PG Distributed Proofreaders. Illustrated HTML file produced by David Widger YORKSHIRE PAINTED AND DESCRIBED BY GORDON HOME Contents CHAPTER I ACROSS THE MOORS FROM PICKERING TO WHITBY CHAPTER II ALONG THE ESK VALLEY CHAPTER III THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO REDCAR CHAPTER IV THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER V Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER VI WHITBY CHAPTER VII THE CLEVELAND HILLS CHAPTER VIII GUISBOROUGH AND THE SKELTON VALLEY CHAPTER IX FROM PICKERING TO RIEVAULX ABBEY CHAPTER X DESCRIBES THE DALE COUNTRY AS A WHOLE CHAPTER XI RICHMOND CHAPTER XII SWALEDALE CHAPTER XIII WENSLEYDALE CHAPTER XIV RIPON AND FOUNTAINS ABBEY CHAPTER XV KNARESBOROUGH AND HARROGATE CHAPTER XVI WHARFEDALE CHAPTER XVII SKIPTON, MALHAM AND GORDALE CHAPTER XVIII SETTLE AND THE INGLETON FELLS CHAPTER XIX CONCERNING THE WOLDS CHAPTER XX FROM FILEY TO SPURN HEAD CHAPTER XXI BEVERLEY CHAPTER XXII ALONG THE HUMBER CHAPTER XXIII THE DERWENT AND THE HOWARDIAN HILLS CHAPTER XXIV A BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE CITY OF YORK CHAPTER XXV THE MANUFACTURING DISTRICT INDEX List of Illustrations 1. -

Roma Subterranea

Roma Subterranea The Catacombs of Late Antique Rome | Marenka Timmermans 0 Illustration front page: After http://www.livescience.com/16318-photos-early-christian-rome-catacombs-artifacts.html 1 Roma Subterranea The Catacombs of Late Antique Rome Marenka Timmermans S0837865 Prof. dr. Sojc Classical Archaeology Leiden University, Faculty of Archaeology Leiden, June 15th, 2012 2 Marenka Timmermans Hogewoerd 141 2311 HK Leiden [email protected] +316-44420389 3 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction 5 1.1 Research goal, methodology and research questions 5 Chapter 2. The origins and further development of the catacombs 7 2.1 Chapter summary 10 Chapter 3. Research performed in the catacombs up to the late 20th century 11 3.1 The 'rediscovery' 11 3.2 Early Catacomb Archaeology 13 3.2.1 Antonio Bosio 13 3.2.2 Giovanni di Rossi 14 3.3 Archaeological research in the late 19th and up to the late 20th century 17 3.4 Chapter conclusion 18 Chapter 4. Modern catacomb research 21 4.1 Demography 21 4.2 Science-based Archaeology 23 4.2.1 Stable isotope analysis 23 4.2.2 Radiocarbon dating 25 4.3 Physical Anthropology 26 4.4 Other sciences in and around the catacombs 27 4.5 Chapter Conclusion 28 Chapter 5. Discussion 31 Chapter 6. Conclusion 37 Summary 39 Samenvatting 41 Bibliography 43 List of Figures 49 List of Tables 51 Appendix I 53 Appendix II 57 3 4 Chapter 1. Introduction The subject of this BA-thesis is the catacombs of Late Antique Rome. The catacombs are formed by large subterranean complexes, consisting of extensive galleries. -

Catacomb Free Ebook

FREECATACOMB EBOOK Madeleine Roux | 352 pages | 14 Jul 2016 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780062364067 | English | New York, United States Catacomb | Definition of Catacomb by Merriam-Webster Preparation work Catacomb not long after a series of gruesome Saint Innocents -cemetery-quarter basement wall collapses added a sense of urgency to the cemetery-eliminating measure, and fromnightly processions of covered wagons transferred remains from most of Paris' cemeteries to a mine shaft opened near the Rue de la Tombe-Issoire. The ossuary remained largely forgotten until it became a novelty-place for Catacomb and other private events Catacomb the Catacomb 19th century; after further renovations and the construction of accesses Catacomb Place Denfert-Rochereau Catacomb, it was open to public visitation from Catacomb ' earliest burial grounds were to the southern outskirts of Catacomb Roman-era Left Bank Catacomb. Thus, instead of burying its dead away from inhabited areas as usual, the Paris Right Bank settlement began with cemeteries near its Catacomb. The most central of these cemeteries, a Catacomb ground around the 5th-century Notre-Dame-des-Bois church, became the property of the Saint-Opportune parish after the original church was demolished by the 9th-century Norman invasions. When it became its own parish associated with the church of the " Saints Innocents " fromthis burial ground, filling the Catacomb between the present rue Saint-Denisrue de la Ferronnerierue de la Lingerie and the Catacomb BergerCatacomb become the City's principal Catacomb. By the end of the same century " Saints Innocents " was neighbour to the principal Catacomb marketplace Les Halles Catacomb, and already filled to overflowing. -

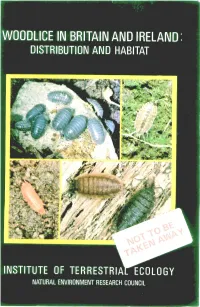

Woodlice in Britain and Ireland: Distribution and Habitat Is out of Date Very Quickly, and That They Will Soon Be Writing the Second Edition

• • • • • • I att,AZ /• •• 21 - • '11 n4I3 - • v., -hi / NT I- r Arty 1 4' I, • • I • A • • • Printed in Great Britain by Lavenham Press NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS ISBN 0 904282 85 6 COVER ILLUSTRATIONS Top left: Armadillidium depressum Top right: Philoscia muscorum Bottom left: Androniscus dentiger Bottom right: Porcellio scaber (2 colour forms) The photographs are reproduced by kind permission of R E Jones/Frank Lane The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE) was established in 1973, from the former Nature Conservancy's research stations and staff, joined later by the Institute of Tree Biology and the Culture Centre of Algae and Protozoa. ITE contributes to, and draws upon, the collective knowledge of the 13 sister institutes which make up the Natural Environment Research Council, spanning all the environmental sciences. The Institute studies the factors determining the structure, composition and processes of land and freshwater systems, and of individual plant and animal species. It is developing a sounder scientific basis for predicting and modelling environmental trends arising from natural or man- made change. The results of this research are available to those responsible for the protection, management and wise use of our natural resources. One quarter of ITE's work is research commissioned by customers, such as the Department of Environment, the European Economic Community, the Nature Conservancy Council and the Overseas Development Administration. The remainder is fundamental research supported by NERC. ITE's expertise is widely used by international organizations in overseas projects and programmes of research. -

Tessa Brings Christmas Cheer

Issue 21 December 10/January 11 North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust The magazine for North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust Tessa brings page 13 Christmas cheer Stop smoking service top of national league The Stockton and Hartlepool stop smoking service is celebrating it’s pole position as top of the Barbara is new national league table for quitters. Figures for 2009/10 show that give them the best possible chance for people who want to quit face in HR the Hartlepool team helped more of quitting, because everyone is cigarettes, including the provision Barbara Bright (pictured) is the people to quit for a four-week different. We’re certainly not there of prescriptions as appropriate. trust’s new deputy director of period (per 100,000 population) to preach! Sessions are held in many different human resources. than any other stop smoking “One of the main causes of people locations including community Following an early career in service. lapsing when they quit is not centres and village halls to improve the NHS, Barbara joined the Service manager Pat Marshall having the right support in the first access to the service and make it University of Teesside where said: “We’re delighted with the place. Their best possible chance easy to call in during a work break she held a number of roles results. Quitting smoking isn’t of success is through using a NHS or on the way home. moving into human resources always easy but it’s something stop smoking service.” in 1996. most smokers really want to do. -

The Story of Our Lighthouses and Lightships

E-STORy-OF-OUR HTHOUSES'i AMLIGHTSHIPS BY. W DAMS BH THE STORY OF OUR LIGHTHOUSES LIGHTSHIPS Descriptive and Historical W. II. DAVENPORT ADAMS THOMAS NELSON AND SONS London, Edinburgh, and Nnv York I/K Contents. I. LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY, ... ... ... ... 9 II. LIGHTHOUSE ADMINISTRATION, ... ... ... ... 31 III. GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OP LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... 39 IV. THE ILLUMINATING APPARATUS OF LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... 46 V. LIGHTHOUSES OF ENGLAND AND SCOTLAND DESCRIBED, ... 73 VI. LIGHTHOUSES OF IRELAND DESCRIBED, ... ... ... 255 VII. SOME FRENCH LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... ... ... 288 VIII. LIGHTHOUSES OF THE UNITED STATES, ... ... ... 309 IX. LIGHTHOUSES IN OUR COLONIES AND DEPENDENCIES, ... 319 X. FLOATING LIGHTS, OR LIGHTSHIPS, ... ... ... 339 XI. LANDMARKS, BEACONS, BUOYS, AND FOG-SIGNALS, ... 355 XII. LIFE IN THE LIGHTHOUSE, ... ... ... 374 LIGHTHOUSES. CHAPTER I. LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY. T)OPULARLY, the lighthouse seems to be looked A upon as a modern invention, and if we con- sider it in its present form, completeness, and efficiency, we shall be justified in limiting its history to the last centuries but as soon as men to down two ; began go to the sea in ships, they must also have begun to ex- perience the need of beacons to guide them into secure channels, and warn them from hidden dangers, and the pressure of this need would be stronger in the night even than in the day. So soon as a want is man's invention hastens to it and strongly felt, supply ; we may be sure, therefore, that in the very earliest ages of civilization lights of some kind or other were introduced for the benefit of the mariner. It may very well be that these, at first, would be nothing more than fires kindled on wave-washed promontories, 10 LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY. -

Able Humber Ports Facility: Extended Phase 1 and Scoping Study (Just Ecology)

Annex 11.1 Able Humber Ports Facility: Extended Phase 1 and Scoping Study (Just Ecology) ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT ABLE UK LTD . X.X1 ABLE HUMBER PORTS FACILITY,KILLINGHOLME: Extended Phase 1 and Scoping Study Strictly Confidential Report to Able UK Limited by Dr Jeff Kirby, Dr Sarah Toogood, David Plant & Vilas Anthwal JUST ECOLOGY May 2006 Just Ecology Environmental Consultancy Ltd. Woodend House, Woodend Wotton-under-Edge Gloucestershire, GL12 8AA www.justecology.co.uk ____________________________________________________________ Reference to sections or particular paragraphs of this document taken out of context may lead to mis-representation Notice to Readers The advice contained in this report is based on the information available and/or collected during the period of study and within the resources available for the project. We cannot completely eliminate the possibility of important ecological features being found through further investigation and/or by survey at different times of the year or in different years. Reference to sections or particular paragraphs of this document taken out of context may lead to mis-representation. JUST ECOLOGY takes care to ensure that balanced advice is provided, based on the information available at the time. ____________________________________________________________ Reference to sections or particular paragraphs of this document taken out of context may lead to mis-representation Abbreviations BAP Biodiversity Action Plan BTO British Trust for Ornithology DEFRA Department for the Environment, -

Into the Deep Naples Short Trip Into the Subterranean City Between Past and Present by Giuseppe

2 to both touristic valorisation and exploitation. Over time, Into the Deep many underground routes have been opened to the pub- lic becoming more and more popular and visited. In that Naples short trip into the Subterra- regard, the catacombs of San Gennaro and the catacombs nean City between past and present of San Gaudioso are two virtuous examples of cultural tourism developed by a project of recovery of under- by Giuseppe Pace, Roberta Varriale, and Elisa Bellato ground historical sites. They are paleo-Christian burials (ISMed-CNR) restored and managed (Catacombs of San Gaudioso in Located in Southern Italy, Naples has about one million inhabitants, administratively subdivided in 10 districts. It is the third largest municipality by population after Rome and Milan. This city has an ancient history with a stratigraphic dimension. In fact, Naples is characterised by a strong interdependence between the aboveground city and its subsoil, with a history that can be read through a sequence of underground layers. The first layer dates back to the Greek colonisation, when the yellow tuff material was used for aboveground buildings, and the underground was excavated for the burial sites and for water supply management. The second layer dates back to Roman times, when the city grew and the underground accommodated new facilities, such as aqueducts, thermal buildings, and catacombs. During the Middle Age, under- Catacombs of San Gennaro (Naples) Photo: G. Pace ground quarries supplied yellow tuff material for sup- porting the intensive aboveground urban development. Once dismissed, those quarries underneath the buildings were adapted as warehouses for local transformation activities or commercial activities. -

Here You’Ll Find the Shownotes, Useful Links and an Episode Transcript – No Email Address Required to Access That

St Hilda Transcript Season 4, Episode 3 Hello, and welcome to the Time Pieces History Podcast. In today’s episode of season four, we’re looking at St Hilda, and it’s inspired by a blog post I wrote for my Time Pieces History Project. One of the categories I looked at was books, choosing 20 of my favourites and exploring the history behind the stories. St Hilda’s Abbey plays a key part in Robin Jarvis’ children’s novel, The Whitby Witches. I’d love to know what you think of these episodes, so please come and find me on Twitter: @GudrunLauret, or leave a comment on your audio player of choice. Alternatively, you can pop a message onto the relevant podcast page over at gudrunlauret.com/podcast, where you’ll find the shownotes, useful links and an episode transcript – no email address required to access that. Hild, or Hilda, was in charge of several monasteries in the mid-600s. She was active in introducing Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons, and her advice was sought by kings from across Britain. Local lad Bede (the Venerable) documented much of her life in his ‘Ecclesiastical History of the English People’, published in 731. Born in 614, Hilda was related to King Edwin of Northumberland and brought up at his royal court. Her father was exiled to the court of one King Elmet, in West Yorkshire, and was poisoned while there. Edwin’s second wife was a Christian, and after their marriage had his entire retinue baptised. Missionaries came from both Ireland (Celtic Christians) and Italy (Roman Christians) to England at around the same time, and it was Paulinus, part of St Augustine’s Roman group, which baptised the family. -

The Orante and the Goddess in the Roman Catacombs

THE ORANTE AND THE GODDESS IN THE ROMAN CATACOMBS Valerie Abrahamsen ABSTRACT The Orante, or Orans, figure, a very common and important symbol in early Christian art, is difficult to interpret. Theories of what she meant to early Christians, especially Roman Christians who buried their dead in the catacombs, range from a representation of the soul of the deceased to a symbol of filial piety. In this article, I will attempt to show that the Orante figure originates with the prehistoric goddess, the all-encom- passing Nature deity worshipped for millennia throughout the Mediterranean world. While many early Christians super- imposed Christian meaning on her, it is likely that other Christians still viewed her in conjunction with the earlier Nature goddess of birth, life, death and rebirth, even as they worshipped God in male form. Introduction he Orante or Orans, generally a female figure with open eyes and upraised hands, is a pervasive symbol in early TChristian art, perhaps “the most important symbol in early Christian art.”1 Found frequently in the late second-century art in the Roman catacombs, as well as in sculpture, her head is almost always covered with a veil, and she wears a tunic. She exists both as a separate symbol and as the main figure in a number of Biblical scenes, but rarely in masculine form with male clothing. Instead, she frequently stands in for male figures in scenes of deliverance—she becomes Noah in the ark, Jonah in the boat and spewed out of the whale, Daniel between the lions, and the three young men in the fiery furnace. -

Changing Minds the Lasting Impact of School Trips

1 Changing Minds The lasting impact of school trips A study of the long-term impact of sustained relationships between schools and the National Trust via the Guardianship scheme Alan Peacock, Honorary Research Fellow, The Innovation Centre, University of Exeter February 2006 CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 2. Introduction to the Guardianship Scheme 2.1 Education outside the classroom: the current debate 2.2 Aims of scheme 2.3 Background to the Scheme - longevity, scale and scope 2.4 Outline of results from the previous evaluation 2.5 Reasons for current evaluation 3. Approach to the Research 3.1 Research objectives 3.2 Evaluation Methodology 3.3 Data gathering approach 3.4 Data analysis 3.5 Difficulties encountered in carrying out LTI studies 3.6 The property schemes evaluated in this study 4. Assessment of Impact and Wider Benefits 4.1 Follow-Up students’ perceptions of long-term impact: 4.1.1 Impact on their attitudes 4.1.2 impact on their skill development 4.1.3 Impact on knowledge and understanding 4.1.4 Evidence of enjoyment, inspiration and creativity 4.1.5 Evidence of changes in activity, behaviour and progression 4.2 Impact on teachers and schools 4.3 Wider benefits to families, friends and the community 4.4 Benefits to staff and volunteers at NT properties 4.5 Summary of findings 5. Recommendations 5.1 Key factors in successful schemes; a ‘template’ 5.2 Future areas for improvement of the Guardianship Scheme 5.3 Final thoughts about “Education outside the Classroom” 6. References 7. Appendices 8.1 Background information on Follow-up students interviewed in schools 8.2: Teachers interviewed 8.3 Interview schedules used 8.4 Introductory letter from NT to schools 8.5 How this study addressed the research objectives 8.6 Case Study 1 1 2 1.