A User's Guide to Natural Resource Efforts in the Red River Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday, June 15, 2017 Thursday, June 15, 2017 2016 Integrated Report - Walsh County

Thursday, June 15, 2017 Thursday, June 15, 2017 2016 Integrated Report - Walsh County Thursday, June 15, 2017 Cart Creek Waterbody ID Waterbody Type Waterbody Description Date TMDL Completed ND-09020310-044-S_00 RIVER Cart Creek from its confluence with A tributary 2 miles east of Mountain, ND downstream to its confluence with North Branch Park River Size Units Beneficial Use Impaired Beneficial Use Status Cause of Impairment TMDL Priority 36.32 MILES Fish and Other Aquatic Biota Not Supporting Fishes Bioassessments L ND-09020310-044-S_00 RIVER Cart Creek from its confluence with A tributary 2 miles east of Mountain, ND downstream to its confluence with North Branch Park River Size Units Beneficial Use Impaired Beneficial Use Status Cause of Impairment TMDL Priority 36.32 MILES Fish and Other Aquatic Biota Not Supporting Benthic-Macroinvertebrate Bioassessments L Forest River Waterbody ID Waterbody Type Waterbody Description Date TMDL Completed ND-09020308-001-S_00 RIVER Forest River from Lake Ardoch, downstream to its confluence with the Red River Of The North. Size Units Beneficial Use Impaired Beneficial Use Status Cause of Impairment TMDL Priority 15.49 MILES Fish and Other Aquatic Biota Not Supporting Benthic-Macroinvertebrate Bioassessments L ND-09020308-001-S_00 RIVER Forest River from Lake Ardoch, downstream to its confluence with the Red River Of The North. Size Units Beneficial Use Impaired Beneficial Use Status Cause of Impairment TMDL Priority 15.49 MILES Fish and Other Aquatic Biota Not Supporting Fishes Bioassessments L ND-09020308-001-S_00 RIVER Forest River from Lake Ardoch, downstream to its confluence with the Red River Of The North. -

Lagimodiere Links

LAGIMODIERE LINKS Winter 2016 What’s happening in Lagimodiere Proudly Supported by the United Way of Winnipeg Letter from your Area Commissioner by Sharon Romanow IN THIS Spring is I look forward to seeing Issue here! And many of you at the upcoming the sound of Provincial Conference being 1 Sharon’s Letter girls selling held at the Hotel Fort Garry. Info 2 Lady Lag Bonnet Award cookies, is available on the Provincial 3 Stats & Registration Info guiders website. Lagimodiere Area has a 4 Want to Try Fishing? planning subsidy available to help with the camps and cost, please ask your DC for more 5 Interlake, Workplace Incentives and Paper advancements, girls working details. towards awards and everyone Project This is also the time of year that 6 70th Girl Guides getting out and about is in the we recognize everyone’s hard air! 7-8 219th Pathfinder work and accomplishments, not Enrolment Lagimodiere Area has had a just the girls but also the Guiders. 9 219th PF learn Animation great Guiding year. Thanks to I am very proud to be your 10 Pattern for a Poncho the exceptional leaders we have Lagimodiere Area Commissioner 11 305th Sparks in our Area, we have grown in when I see our older girls receive membership by 6.69% when the their Gold Commissioner Awards 11 303rd Guides National average is only 0.68%! and Canada Cords, as I present 14-16 219th B Brownies Thank-you to everyone for their the younger ones with their Lady 17 Grand Pines Resource great work in promoting Guiding. -

CMPS Annual Business Meeting Minutes, 1954-2018

CMPS Annual Business Meeting Minutes, 1954-2018 1954 February 20: Colorado A & M College, Ft. Collins, Colorado. As Part of the Foresters’ Days Program, Lee Yeager, Regional Representative, Region IV, called a meeting at 2:00 p.m. to discuss The Wildlife Society and its objectives. After remarks on Society news and activities, discussion was opened on the question “Should we organize a Section or other formal body of Wildlife Society members for all or a part of Region IV?” Taking part in this discussion were Lee Yeager, J. V. K. Wagar, Art Eustis, Dr. Sooter, Dr. E. Kalmbach, Johnson Neff, Ralph Hill, Jim Grasse, Reed Fautin, John Scott, Richard Beidleman, Harold Steinhoff, and C. E. Till. Smoky Till moved that “we form a definite organization for Region IV with a President, Vice-President, and Secretary/Treasurer to perfect the organization.” Twenty-three voted for and 1 voted against this motion. Society members thus formally approved the Central Mountains and Plains Section. Harold Steinhoff was acting Secretary. October 28: Lee Yeager, Region IV Representative, in an annual report to TWS members in the region, mentioned that “Region IV is too big…we are in the process of organizing a Section composed of the Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, and Wyoming membership,” and that “other Sections in the region might be beneficial to the Society and our profession.” During the fall of the year, an election of officers was held. 1955 January 26: One hundred six (106) votes were counted for the election of officers and the results were reported to the Regional Representative. -

DATE: March 20, 2018 TO: Board of Water and Soil Resources

DATE: March 20, 2018 TO: Board of Water and Soil Resources’ Members, Advisors, and Staff FROM: John Jaschke, Executive Director SUBJECT: BWSR Board Meeting Notice – March 28, 2018 The Board of Water and Soil Resources (BWSR) will meet on Wednesday, March 28, 2018, beginning at 9:00 a.m. The meeting will be held in the lower level Board Room, at 520 Lafayette Road, Saint Paul. Parking is available in the lot directly in front of the building (see hooded parking area). The following information pertains to agenda items: COMMITTEE RECOMMENDATIONS Water Management and Strategic Planning Committee One Watershed, One Plan Operating Procedures and Plan Content Requirements – The One Watershed, One Plan Operating Procedures and Plan Content Requirements are the two policy documents that describe program requirements according to Minnesota Statutes §103B.801. These documents, which were based on policies for the pilot program (developed in 2014), were updated in 2016 when the program was formally established. Since that time, BWSR’s Water Planning Program Team has identified a need to improve the organization and clarity of these documents, along with minor changes to policy elements. The team recommends re-formatting both documents with the new State of Minnesota logo and style. For both documents, the majority of non-policy information (background, context, and optional items) have been removed. DECISION Other changes include: • Policy o High level summary of changes (see the last page of each document for more detail) • Operating Procedures o Removed automatic exemption for LGUs with less than 5% of their area in the planning boundary o Added requirements for sharing public comments during the plan review and approval process • Plan Content Requirements o Land and Water Resources Inventory changed to Narrative; added requirement for discussion of watershed context o Fairly extensive wording changes in Plan Administration and Implementation Programs sections resulting in minor changes to policy elements. -

Water Availability and Drought Conditions Report MAY 2021

Water Availability and Drought Conditions Report MAY 2021 Executive Summary This Water Availability and Drought Conditions Report provides an update on conditions throughout Manitoba for May 2021. As of May 31, 2021, conditions remain dry across southern Manitoba with varied impacts occurring to water users including municipalities and water co- ops and to crop and livestock producers. For more information on conditions, indicators, and resources for those impacted by dry conditions, please visit the Manitoba Drought Monitor at www.manitoba.ca/drought Precipitation conditions over the past month, three month, and twelve month periods are as follows: o During May, most of agri-Manitoba experienced moderately dry (60 – 85 % of median) to severely dry (40 – 60 %) conditions. In northern Manitoba conditions were moderately dry in the east. However, normal (85 – 115 %) to above normal (> 115 %) precipitation was received in the north and western portions of northern Manitoba. o Over the past three months (March, April, May), most of southern Manitoba experienced severely dry to extremely dry (< 40 %) conditions, except for eastern agri-Manitoba where moderately dry to normal conditions were observed. Conditions in northern Manitoba were moderately to severely dry in the east and normal to above normal in the west. o Over the past 12 months, most of agri-Manitoba observed moderately dry conditions with regions of severe dryness in the Interlake, central, and southwest regions. Conditions in northern Manitoba were normal to above normal. As of June 1, 2021, most rivers and lakes across southern Manitoba were showing below normal (10th – 25th percentile) to much below normal (< 10th percentile) conditions. -

Valid Operating Permits

Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality Region Number Facility 20525 WOODLANDS SHELL UST Woodlands Interlake 20532 TRAPPERS DOMO UST Alexander Eastern 55141 TRAPPERS DOMO AST Alexander Eastern 20534 LE DEPANNEUR UST La Broquerie Eastern 63370 LE DEPANNEUR AST La Broquerie Eastern 20539 ESSO - THE PAS UST The Pas Northwest 20540 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN UST Virden Western 20542 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN AST Virden Western 20545 RAMERS CARWASH AND GAS UST Beausejour Eastern 20547 CLEARVIEW CO-OP - LA BROQUERIE GAS BAR UST La Broquerie Red River 20551 FEHRWAY FEEDS AST Ridgeville Red River 20554 DOAK'S PETROLEUM - The Pas AST Gillam Northeast 20556 NINETTE GAS SERVICE UST Ninette Western 20561 RW CONSUMER PRODUCTS AST Winnipeg Red River 20562 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 29143 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 42388 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 42390 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 20563 MISERICORDIA HEALTH CENTRE AST Winnipeg Red River 20564 SUN VALLEY CO-OP - 179 CARON ST UST St. Jean Baptiste Red River 20566 BOUNDARY CONSUMERS CO-OP - DELORAINE AST Deloraine Western 20570 LUNDAR CHICKEN CHEF & ESSO UST Lundar Interlake 20571 HIGHWAY 17 SERVICE UST Armstrong Interlake 20573 HILL-TOP GROCETERIA & GAS UST Elphinstone Western 20584 VIKING LODGE AST Cranberry Portage Northwest 20589 CITY OF BRANDON AST Brandon Western 1 Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality -

Fishing the Red River of the North

FISHING THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH The Red River boasts more than 70 species of fish. Channel catfish in the Red River can attain weights of more than 30 pounds, walleye as big as 13 pounds, and northern pike can grow as long as 45 inches. Includes access maps, fishing tips, local tourism contacts and more. TABLE OF CONTENTS YOUR GUIDE TO FISHING THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH 3 FISHERIES MANAGEMENT 4 RIVER STEWARDSHIP 4 FISH OF THE RED RIVER 5 PUBLIC ACCESS MAP 6 PUBLIC ACCESS CHART 7 AREA MAPS 8 FISHING THE RED 9 TIP AND RAP 9 EATING FISH FROM THE RED RIVER 11 CATCH-AND-RELEASE 11 FISH RECIPES 11 LOCAL TOURISM CONTACTS 12 BE AWARE OF THE DANGERS OF DAMS 12 ©2017, State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resources FAW-471-17 The Minnesota DNR prohibits discrimination in its programs and services based on race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, public assistance status, age, sexual orientation or disability. Persons with disabilities may request reasonable modifications to access or participate in DNR programs and services by contacting the DNR ADA Title II Coordinator at [email protected] or 651-259-5488. Discrimination inquiries should be sent to Minnesota DNR, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4049; or Office of Civil Rights, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C. Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20240. This brochure was produced by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Fish and Wildlife with technical assistance provided by the North Dakota Department of Game and Fish. -

Approaches to Setting Nutrient Targets in the Red River of the North

APPROACHES TO SETTING NUTRIENT TARGETS IN THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH Topical Report RSI-2328 prepared for International Joint Commission 1250 23rd St. NW, Room 100 Washington, DC 20440 March 2013 APPROACHES TO SETTING NUTRIENT TARGETS IN THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH Topical Report RSI-2328 by Andrea B. Plevan Julie A. Blackburn RESPEC 1935 West County Road B2, Suite 320 Roseville, MN 55113 prepared for International Joint Commission 1250 23rd St. NW, Room 100 Washington, DC 20440 March 2013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The International Joint Commission, through its International Red River Board (IRRB), has developed a proposed approach for a basinwide nutrient management strategy for the international Red River Watershed. One component of the nutrient management strategy involves developing nitrogen and phosphorus targets along the Red River including sites at the outlet of the Red River into Lake Winnipeg, the international boundary at Emerson, and subwatershed discharge points in the watershed. These nutrient objectives will be coordinated with developing nutrient objectives for Lake Winnipeg. As a first step in developing the nutrient targets, the IRRB contracted RESPEC to conduct a literature review of the available scientific methods for setting nitrogen and phosphorus water-quality targets. Based on the findings of the literature review, RESPEC was asked to provide recommendations on the method(s) most appropriate for the Red River. This report includes the findings of the literature review and the recommended scientific approaches for developing nitrogen and phosphorus targets in the Red River. Multiple technical approaches were reviewed. One category of approaches uses the reference condition and includes techniques such as using data from reference sites, modeling the reference condition, estimating the reference condition from all sites within a class, and paleolimnological techniques to reconstruct the reference condition through historical data. -

Guide Des Collectivités Des Premières Nations

Guide des Collectivités des Premières nations Région du Manitoba 2012-2013 Premières nations du Manitoba En mars 2012, le Manitoba comptait 140,975 membres inscrits des Premières nations, dont 84,874 membres (60,2 p. cent) habitent dans les réserves. Ce pourcentage place le Manitoba au deuxième rang derrière l’Ontario au chapitre du nombre total de personnes vivant dans les réserves et de la population autochtone totale à l’échelle provinciale. Le rapport intitulé Population indienne inscrite selon le sexe et la résidence 2012 confirme que 84,303 (59,8 p. cent) des membres des Premières nations au Manitoba sont âgés de moins de 30 ans. Au Manitoba il y a 63 Premières nations, parmi lesquelles on retrouve 6 des 20 plus importantes bandes indiennes au Canada. On note aussi que 23 Premières nations ne disposent pas de route d’accès praticable en tout temps. Ce dilemme touche plus de la moitié de tous les membres des Premières nations qui vivent dans les réserves. Il existe cinq groupes linguistiques au sein des Premières nations du Manitoba: cri, ojibway, dakota, oji-cri et déné. À l’exception de cinq Premières nations du Manitoba - sioux Birdtail, Sioux Valley, Canupawakpa, Dakota Tipi et Dakota Plains - qui ne sont signataires d’aucun traité avec le Canada, celui-ci a signé sept traités, soit les traités nos 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, avec toutes les autres Premières nations de la province. Les Premières nations du Manitoba sont représentées par trois organismes politiques provinciaux répartis selon un axe nord-sud. Principale organisation politique, l’Assemblée des chefs du Manitoba représente 59 chefs du Manitoba. -

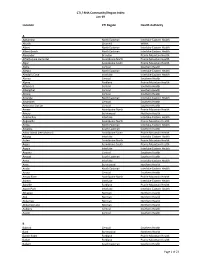

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

NWSI 10-903, Geographic Areas Of

Department of Commerce • National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration • National Weather Service NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE INSTRUCTION 10-903 JULY 26, 2019 Operations and Services Water Resources Services Program, NWSPD 10-9 GEOGRAPHIC AREAS OF RESPONSIBILITY NOTICE: This publication is available at: http://www.nws.noaa.gov/directives/ OPR: W/AFS25 (K. Abshire) Certified by: W/AFS25 (M. Mullusky) Type of Issuance: Routine. SUMMARY OF REVISIONS: This directive supersedes NWS Instruction 10-903, “Geographic Areas of Responsibility,” dated February 16, 2017. The following revisions were made to this instruction: 1) In Section 2, updated the link to the RFC boundary shapefiles from the NWS geographic information system (GIS) Portal. 2) In Section 2, updated the location of the Northeast RFC (NERFC) from Taunton to Norton, Massachusetts. 3) In Section 3, updated Figure 2 to show correct Hydrologic Service Area (HSA) boundaries and Weather Forecast Office three-letter identifiers. 4) In Section 3, updated the link to the national Hydrologic Service Area (HSA) map from the NWS geographic information system (GIS) Portal. 5) In Section 3, modified wording to describe the Boston/Norton, MA (BOX), Gray/Portland, ME (GYX), Nashville, TN (OHX) service areas and updated the office names of the New York, NY (OKX) and Philadelphia/Mt. Holly, PA (PHI) offices. Signed 7/12/2019 Andrew D. Stern Date Director Analyze, Forecast, and Support Office NWSI 10-903 JULY 26, 2019 Geographic Areas of Responsibility Table of Contents: Page 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................1 -

Lateral Migration of the Red River, in the Vicinity of Grand Forks, North Dakota Dylan Babiracki

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Undergraduate Theses and Senior Projects Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 2015 Lateral Migration of the Red River, in the Vicinity of Grand Forks, North Dakota Dylan Babiracki Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/senior-projects Recommended Citation Babiracki, Dylan, "Lateral Migration of the Red River, in the Vicinity of Grand Forks, North Dakota" (2015). Undergraduate Theses and Senior Projects. 114. https://commons.und.edu/senior-projects/114 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses and Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. | 1 Lateral migration of the Red River, in the vicinity of Grand Forks, North Dakota Dylan Babiracki Harold Hamm School of Geology and Geologic Engineering, University of North Dakota, 81 Cornell St., Grand Forks, ND 58202-8358 1. Abstract River channels are dynamic landforms that play an important role in understanding the alluvial changes occurring within this area. The evolution of the Red River of the North within the shallow alluvial valley was investigated within a 60 river mile area north and south of Grand Forks, North Dakota. Despite considerable research along the Red River of the North, near St. Jean Baptiste, Manitoba, little is known about the historical channel dynamics within the defined study area. A series of 31 measurements were taken using three separate methods to document the path of lateral channel migration along areas of this highly sinuous, low- gradient river.