The Best Loser System in Mauritius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sadc Electoral Observation Mission to the Republic of Mauritius Statement by the Hon. Maite Nkoana-Mashabane (Mp) Minister of In

SADC ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION TO THE REPUBLIC OF MAURITIUS STATEMENT BY THE HON. MAITE NKOANA-MASHABANE (MP) MINISTER OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND COOPERATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA AND HEAD OF THE SADC ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION TO THE 2014 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS IN THE REPUBLIC OF MAURITIUS, DELIVERED ON 11 DECEMBER 2014 Moka, Republic of Mauritius Mr. Abdool Rahman, Electoral Commissioner, Your Excellency, Dr Aminata Touré, Head of the African Union (AU) Election Observation Mission, Honourable Ellen Molekane, Deputy Minister of State Security of the Republic of South Africa, Ambassador Julius Tebello Metsing of the Kingdom of Lesotho, the incoming Chairperson and Ambassador Theresia Samaria of the Republic of Namibia, representing outgoing Chairperson of the SADC Organ Troika, respectively, Your Excellency, Ms. Emilie Mushobekwa, SADC Deputy Executive Secretary, Fellow Heads of International Electoral Observation Missions, High Commissioners, Ambassadors, and other Members of the Diplomatic Corps, Esteemed Leaders of Political Parties and Independent Candidates, Members of the Media and of Civil Society Organisations, 2 Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, We are gathered here this morning to share with you the preliminary findings of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Electoral Observation Mission (SEOM) to the National Assembly Elections in the Republic of Mauritius, held on 10 December 2014. We thank you for graciously honouring our invitation. Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, This year we have witnessed an unprecedented number of elections in the SADC region, in Malawi, South Africa, Mozambique, Botswana and Namibia. On Wednesday, 10 December, the people of Mauritius also participated in this festival of democracy. In January and February 2015, the Republic of Zambia and the Kingdom of Lesotho, will also go to the polls. -

Debate No 35 of 2018 (UNREVISED)

1 No. 35 of 2018 SIXTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) (UNREVISED) FIRST SESSION FRIDAY 07 DECEMBER 2018 2 CONTENTS PAPERS LAID QUESTION (Oral) MOTION ANNOUNCEMENT BILL (Public) ADJOURNMENT 3 THE CABINET (Formed by Hon. Pravind Kumar Jugnauth) Hon. Pravind Kumar Jugnauth Prime Minister, Minister of Home Affairs, External Communications and National Development Unit, Minister of Finance and Economic Development Hon. Ivan Leslie Collendavelloo, GCSK, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Energy and Public SC Utilities Hon. Sir Anerood Jugnauth, GCSK, Minister Mentor, Minister of Defence, Minister for KCMG, QC Rodrigues Hon. Mrs Fazila Jeewa-Daureeawoo Vice-Prime Minister, Minister of Local Government and Outer Islands, Minister of Gender Equality, Child Development and Family Welfare Hon. Seetanah Lutchmeenaraidoo, GCSK Minister of Foreign Affairs, Regional Integration and International Trade Hon. Yogida Sawmynaden Minister of Technology, Communication and Innovation Hon. Nandcoomar Bodha, GCSK Minister of Public Infrastructure and Land Transport Hon. Mrs Leela Devi Dookun-Luchoomun Minister of Education and Human Resources, Tertiary Education and Scientific Research Hon. Anil Kumarsingh Gayan, SC Minister of Tourism Dr. the Hon. Mohammad Anwar Husnoo Minister of Health and Quality of Life Hon. Prithvirajsing Roopun Minister of Arts and Culture Hon. Marie Joseph Noël Etienne Ghislain Minister of Social Security, National Solidarity, and Sinatambou Environment and Sustainable Development Hon. Mahen Kumar Seeruttun Minister of Agro-Industry and Food Security Hon. Ashit Kumar Gungah Minister of Industry, Commerce and Consumer Protection Hon. Maneesh Gobin Attorney General, Minister of Justice, Human Rights and Institutional Reforms Hon. Jean Christophe Stephan Toussaint Minister of Youth and Sports Hon. Soomilduth Bholah Minister of Business, Enterprise and Cooperatives 4 Hon. -

Debate No 37 of 2018 (UNREVISED)

1 No. 37 of 2018 SIXTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) (UNREVISED) FIRST SESSION MONDAY 10 DECEMBER 2018 2 CONTENTS PAPERS LAID MOTION BILL (Public) ADJOURNMENT 3 THE CABINET (Formed by Hon. Pravind Kumar Jugnauth) Hon. Pravind Kumar Jugnauth Prime Minister, Minister of Home Affairs, External Communications and National Development Unit, Minister of Finance and Economic Development Hon. Ivan Leslie Collendavelloo, GCSK, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Energy and Public SC Utilities Hon. Sir Anerood Jugnauth, GCSK, Minister Mentor, Minister of Defence, Minister for KCMG, QC Rodrigues Hon. Mrs Fazila Jeewa-Daureeawoo Vice-Prime Minister, Minister of Local Government and Outer Islands, Minister of Gender Equality, Child Development and Family Welfare Hon. Seetanah Lutchmeenaraidoo, GCSK Minister of Foreign Affairs, Regional Integration and International Trade Hon. Yogida Sawmynaden Minister of Technology, Communication and Innovation Hon. Nandcoomar Bodha, GCSK Minister of Public Infrastructure and Land Transport Hon. Mrs Leela Devi Dookun-Luchoomun Minister of Education and Human Resources, Tertiary Education and Scientific Research Hon. Anil Kumarsingh Gayan, SC Minister of Tourism Dr. the Hon. Mohammad Anwar Husnoo Minister of Health and Quality of Life Hon. Prithvirajsing Roopun Minister of Arts and Culture Hon. Marie Joseph Noël Etienne Ghislain Minister of Social Security, National Solidarity, and Sinatambou Environment and Sustainable Development Hon. Mahen Kumar Seeruttun Minister of Agro-Industry and Food Security Hon. Ashit Kumar Gungah Minister of Industry, Commerce and Consumer Protection Hon. Maneesh Gobin Attorney General, Minister of Justice, Human Rights and Institutional Reforms Hon. Jean Christophe Stephan Toussaint Minister of Youth and Sports Hon. Soomilduth Bholah Minister of Business, Enterprise and Cooperatives 4 Hon. -

Social Democracy in Mauritius

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository Development with Social Justice? Social Democracy in Mauritius Letuku Elias Phaahla 15814432 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (International Studies) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Janis van der Westhuizen March 2010 ii Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Signature:……………………….. Date:…………………………….. iii To God be the glory My dearly beloved late sisters, Pabalelo and Kholofelo Phaahla The late Leah Maphankgane The late Letumile Saboshego I know you are looking down with utmost pride iv Abstract Since the advent of independence in 1968, Mauritius’ economic trajectory evolved from the one of a monocrop sugar economy, with the latter noticeably being the backbone of the country’s economy, to one that progressed into being the custodian of a dynamic and sophisticated garment-dominated manufacturing industry. Condemned with the misfortune of not being endowed with natural resources, relative to her mainland African counterparts, Mauritius, nonetheless, was able to break the shackles of limited economic options and one of being the ‘basket-case’ to gradually evolving into being the upper-middle-income country - thus depicting it to be one of the most encouraging economies within the developing world. -

Mauritius Country Report BTI 2018

BTI 2018 Country Report Mauritius This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Mauritius. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Mauritius 3 Key Indicators Population M 1.3 HDI 0.781 GDP p.c., PPP $ 21088 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.1 HDI rank of 188 64 Gini Index 35.8 Life expectancy years 74.4 UN Education Index 0.758 Poverty3 % 3.2 Urban population % 39.5 Gender inequality2 0.380 Aid per capita $ 60.6 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Mauritius is not a transformation country in the classic sense. -

SUMMARY RECORDS of the PROCEEDINGS of the 128Th IPU ASSEMBLY Quito (Ecuador) 22-27 March 2013

SUMMARY RECORDS OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 128th IPU ASSEMBLY Quito (Ecuador) 22-27 March 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page(s) Introduction ............................................................................................................ 5 Inaugural ceremony · Speech by Mr. Fernando Cordero Cueva, Speaker of the National Assembly of Ecuador .......................................................................................................... 6 · Speech by Mr. Philippe Douste-Blazy, United Nations Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser on Innovative Financing for Development .......................... 6 · Speech by Mr. Abdelwahad Radi, President of the Inter-Parliamentary Union ..... 7 · Speech by Mr. Rafael Correa Delgado, President of the Republic of Ecuador ..... 8 Organization of the work of the Assembly · Election of the President and Vice-Presidents of the 128th Assembly and opening of the General Debate ........................................................................................ 11 · Consideration of requests for the inclusion of an emergency item in the Assembly agenda .......................................................................................... 26 29 · Final Assembly Agenda ...................................................................................... General Debate on the overall theme: From unrelenting growth to purposeful development “buen vivir": New approaches, new solutions ......................................... 11 · Interactive dialogue session on the place of democratic -

BTI 2020 Country Report Mauritius

BTI 2020 Country Report Mauritius This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2020. It covers the period from February 1, 2017 to January 31, 2019. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of governance in 137 countries. More on the BTI at https://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2020 Country Report — Mauritius. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2020. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2020 | Mauritius 3 Key Indicators Population M 1.3 HDI 0.796 GDP p.c., PPP $ 23709 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.1 HDI rank of 189 66 Gini Index 38.5 Life expectancy years 74.5 UN Education Index 0.730 Poverty3 % 3.0 Urban population % 40.8 Gender inequality2 0.369 Aid per capita $ 9.2 Sources (as of December 2019): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2019 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2019. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Mauritius is not a transformation country in the classic sense. -

Despite Concerns About Electoral Commission and Conflict, Mauritians Value Open Elections

Dispatch No. 327 | 4 November 2019 Despite concerns about electoral commission and conflict, Mauritians value open elections Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 327 | Sadhiska Bhoojedhur and Thomas Isbell Summary During the first weekend of October, the Mauritian prime minister dissolved Parliament and called a general election for November 7 – a surprise announcement that left both the electoral commission and political parties scrambling (Weekly, 2019). The current government has claimed several high-visibility successes, including the launch of the Metro Express light-rail public transport system, the elimination of some university fees for students, the introduction of minimum salary compensation and a negative income tax, and the inauguration of a sports complex (Duymun, 2018; Seegobin, 2019). But critics point to persistent challenges such as unemployment, corruption, and weaknesses in delivering health care, education, and other public services (Duymun, 2018). In light of the upcoming election, this dispatch uses Afrobarometer survey data from 2012- 2017 to explore popular attitudes toward elections among ordinary Mauritians. We find that while Mauritians overwhelmingly feel that their last national election was free and fair, their trust in the electoral commission has declined sharply. Nonetheless, most citizens support elections as the best way to choose their leaders and want multiparty competition to ensure that voters have real choices. Citizens’ priorities for government action, as of late 2017, were unemployment, poverty, and crime – issues on which the government’s performance received poor marks. Afrobarometer survey Afrobarometer heads a pan-African, nonpartisan research network that conducts public attitude surveys on democracy, governance, economic conditions, and related issues across Africa. Seven rounds of surveys were completed in up to 38 countries between 1999 and 2018. -

Mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility Legislation Around the World: Emergent Varieties and National Experiences

MANDATORY CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY LEGISLATION AROUND THE WORLD: EMERGENT VARIETIES AND NATIONAL EXPERIENCES Li-Wen Lin* INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 430 I.MANDATORY CSR DUE DILIGENCE............................................... 434 A. National Experience: France........................................... 435 II.MANDATORY CORPORATE PHILANTHROPY.................................. 439 A. National Experience (1): Mauritius ................................ 440 B. National Experience (2): India........................................ 442 III.MANDATORY CSR GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE........................... 445 A. National Experience: South Africa................................. 446 IV.MANDATORY GENERAL CSR DUTY (UNDER CORPORATE LAW) 449 A. National Experience (1): China ...................................... 449 B. National Experience (2): Indonesia ................................ 453 V.EVALUATION................................................................................. 457 A. The Impetus of the Law.................................................. 457 B. The Scope of Corporations Subject to the Law.............. 459 C. The Definition of CSR.................................................... 460 D. The Implementation of the Law ..................................... 461 E. The Function of the Law ................................................ 463 F. The Relationship Between the Laws and Beyond .......... 464 G. The Reform of the Law ................................................. -

Report of the Commission on Constitutional and Electoral Reform 2001/02

REPORT OF THE COMMISSION ON CONSTITUTIONAL AND ELECTORAL REFORM 2001/02 Introduction 1. In a society as lively and politically literate as Mauritius, it is not surprising that the Commission for Constitutional and Electoral Reform1 should be inundated with submissions2. Over a period of several weeks we received more than seventy written memoranda and heard oral representations during more than fifty sessions. We also organised three public sessions in Mauritius and one in Rodrigues. The task of sifting through the great mass of material was considerably assisted by the fact that, whether they came from organised political parties, cultural groups or concerned individuals, the depositions were forceful and articulate. We would like to express our appreciation to all the many persons, both exalted and humble, who contributed information, ideas and perspectives. In equal measure, we thank the Mauritian support team, whose outstanding logistical and administrative backup enabled us to handle this vast mass of material with great expedition. 2. If the volume of material was not unexpected, what was surprising, given the robust nature of political life in Mauritius, was the relatively high degree of consensus on the need for change in a number of key areas. Thus, virtually all the deponents accepted the idea that steps should be taken to strengthen guarantees of free and fair elections, particularly with regard to speed, security, finance and the need for an extensive code of conduct monitored by a strong and independent electoral supervisory body. There was also widespread acceptance of the necessity to correct the gross under-representation of opposition parties produced by the electoral system. -

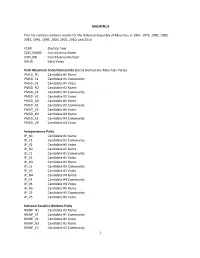

1 MAURITIUS This File Contains Election Results for the National

MAURITIUS This file contains election results for the National Assembly of Mauritius in 1967, 1976, 1982, 1983, 1987, 1991, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2014. YEAR Election Year CON_NAME Constituency Name CON_NO Constituency Number VALID Valid Votes Parti Mauricien Social Democrate (Social Democratic Mauritian Party) PMSD_N1 Candidate #1 Name PMSD_C1 Candidate #1 Community PMSD_V1 Candidate #1 Votes PMSD_N2 Candidate #2 Name PMSD_C2 Candidate #2 Community PMSD_V2 Candidate #2 Votes PMSD_N3 Candidate #3 Name PMSD_C3 Candidate #3 Community PMSD_V3 Candidate #3 Votes PMSD_N4 Candidate #4 Name PMSD_C4 Candidate #4 Community PMSD_V4 Candidate #4 Votes Independence Party IP_N1 Candidate #1 Name IP_C1 Candidate #1 Community IP_V1 Candidate #1 Votes IP_N2 Candidate #2 Name IP_C2 Candidate #2 Community IP_V2 Candidate #2 Votes IP_N3 Candidate #3 Name IP_C3 Candidate #3 Community IP_V3 Candidate #3 Votes IP_N4 Candidate #4 Name IP_C4 Candidate #4 Community IP_V4 Candidate #4 Votes IP_N5 Candidate #5 Name IP_C5 Candidate #5 Community IP_V5 Candidate #5 Votes National Socialist Workers Party NSWP_N1 Candidate #1 Name NSWP_C1 Candidate #1 Community NSWP_V1 Candidate #1 Votes NSWP_N2 Candidate #2 Name NSWP_C2 Candidate #2 Community 1 NSWP_V2 Candidate #2 Votes NSWP_N3 Candidate #3 Name NSWP_C3 Candidate #3 Community NSWP_V3 Candidate #3 Votes Mauritius Young Communist League MYCL_N1 Candidate #1 Name NYCL_C1 Candidate #1 Community MYCL_V1 Candidate #1 Votes Mauritius Liberation Front MLF_N1 Candidate #1 Name MLF_C1 Candidate #1 Community MLF_V1 Candidate -

Dimpho Motsamai

EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR ELECTORAL SUPPORT ESN - SA ELECTORAL SUPPORT NETWORK IN SOUTHERN AFRICA Democratic Republic of Congo United Republic PREVENTING AND of MITIGATINGTanzania ELECTORAL CONFLICTSeychelles Angola AND VIOLENCEMozambique Zambia Malawi Mauritius Madagascar ZimbabweFabio Bargiacchi, Victoria Florinder Editors Namibia Botswana Kondwani Chirambo, Thibaud Kurtz Co-editors Swaziland South Africa Lesotho Funded 75% by The European Union and 25% by The European Centre for Electoral Support Table of Content FOREWORD 2 PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 10 CHAPTER I - ELECTORAL CONFLICT PREVENTION FRAMEWORK 16 Handbook Purpose and Goal 17 Defining Election Related Conflict and Research Framework 19 A Regional Journey About Preventing Electoral Violence 19 Early Warning 28 CHAPTER II - CASE STUDIES 30 Regional SADC and Botswana / Kondwani Chirambo 31 Angola / Celestino Onesimo Setucula 61 Democratic Republic of the Congo / Robert Gerenge 76 Lesotho / Victor Shale 101 Madagascar / Juvence Ramasy 128 Malawi / Henry Chingaipe 148 Mauritius / Catherine Boudet 180 Mozambique / Johanna Nilsson 205 Namibia / Maximilian Weiland 230 South Africa / Dimpho Motsamai 255 Swaziland / Lungile Mnisi 278 United Republic of Tanzania and Zanzibar / Andrew Mushi and Alexander Makulilo 303 Zambia / Lee Habasonda 326 Zimbabwe / Jestina Mukoko 350 CHAPTER III - CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION 378 Key Findings for the Region 379 Shared Regional Issues from the Case Studies 379 Regional Issues 382 Unique National Issues with Potential for Regional Focus 382 Conclusions 384