Alternative Formats If You Require This Document in an Alternative Format, Please Contact: [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spontaneous Generation & Origin of Life Concepts from Antiquity to The

SIMB News News magazine of the Society for Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology April/May/June 2019 V.69 N.2 • www.simbhq.org Spontaneous Generation & Origin of Life Concepts from Antiquity to the Present :ŽƵƌŶĂůŽĨ/ŶĚƵƐƚƌŝĂůDŝĐƌŽďŝŽůŽŐLJΘŝŽƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐLJ Impact Factor 3.103 The Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology is an international journal which publishes papers in metabolic engineering & synthetic biology; biocatalysis; fermentation & cell culture; natural products discovery & biosynthesis; bioenergy/biofuels/biochemicals; environmental microbiology; biotechnology methods; applied genomics & systems biotechnology; and food biotechnology & probiotics Editor-in-Chief Ramon Gonzalez, University of South Florida, Tampa FL, USA Editors Special Issue ^LJŶƚŚĞƚŝĐŝŽůŽŐLJ; July 2018 S. Bagley, Michigan Tech, Houghton, MI, USA R. H. Baltz, CognoGen Biotech. Consult., Sarasota, FL, USA Impact Factor 3.500 T. W. Jeffries, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA 3.000 T. D. Leathers, USDA ARS, Peoria, IL, USA 2.500 M. J. López López, University of Almeria, Almeria, Spain C. D. Maranas, Pennsylvania State Univ., Univ. Park, PA, USA 2.000 2.505 2.439 2.745 2.810 3.103 S. Park, UNIST, Ulsan, Korea 1.500 J. L. Revuelta, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain 1.000 B. Shen, Scripps Research Institute, Jupiter, FL, USA 500 D. K. Solaiman, USDA ARS, Wyndmoor, PA, USA Y. Tang, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA E. J. Vandamme, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium H. Zhao, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL, USA 10 Most Cited Articles Published in 2016 (Data from Web of Science: October 15, 2018) Senior Author(s) Title Citations L. Katz, R. Baltz Natural product discovery: past, present, and future 103 Genetic manipulation of secondary metabolite biosynthesis for improved production in Streptomyces and R. -

Malpighi, Swammerdam and the Colourful Silkworm: Replication and Visual Representation in Early Modern Science

Annals of Science, 59 (2002), 111–147 Malpighi, Swammerdam and the Colourful Silkworm: Replication and Visual Representation in Early Modern Science Matthew Cobb Laboratoire d’Ecologie, CNRS UMR 7625, Universite´ Paris 6, 7 Quai St Bernard, 75005 Paris, France. Email: [email protected] Received 26 October 2000. Revised paper accepted 28 February 2001 Summary In 1669, Malpighi published the rst systematic dissection of an insect. The manuscript of this work contains a striking water-colour of the silkworm, which is described here for the rst time. On repeating Malpighi’s pioneering investi- gation, Swammerdam found what he thought were a number of errors, but was hampered by Malpighi’s failure to explain his techniques. This may explain Swammerdam’s subsequent description of his methods. In 1675, as he was about to abandon his scienti c researches for a life of religious contemplation, Swammerdam destroyed his manuscript on the silkworm, but not before sending the drawings to Malpighi. These gures, with their rich and unique use of colour, are studied here for the rst time. The role played by Henry Oldenburg, secretary of the Royal Society, in encouraging contact between the two men is emphasized and the way this exchange reveals the development of some key features of modern science — replication and modern scienti c illustration — is discussed. Contents 1. Introduction . 111 2. Malpighi and the silkworm . 112 3. The silkworm reveals its colours . 119 4. Swammerdam and the silkworm . 121 5. Swammerdam replicates Malpighi’s work . 124 6. Swammerdam publicly criticizes Malpighi . 126 7. Oldenburg tries to play the middle-man . -

Weber's Science As a Vocation

JCS0010.1177/1468795X19851408Journal of Classical SociologyShapin 851408research-article2019 Article Journal of Classical Sociology 1 –18 Weber’s Science as a © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: Vocation: A moment in the sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/1468795X19851408DOI: 10.1177/1468795X19851408 history of “is” and “ought” journals.sagepub.com/home/jcs Steven Shapin Harvard University, USA Abstract This essay situates Weber’s 1917 lecture Science as a Vocation in relevant historical contexts. The first context is thought about the changing nature of the scientific role and its place in institutions of higher education, and attention is drawn to broadly similar sentiments expressed by Thorstein Veblen. The second context is that of scientific naturalism and materialism and related sentiments about the “conflicts” between natural science and religion. Finally, there is the context of Weber’s lecture as a performance played out before a specific academic audience at the University of Munich, and the essay suggests the pertinence of that performance to an appreciation of the lecture’s meaning. Keywords Max Weber, vocation, science, Thorstein Veblen, scientific naturalism, scientific materialism Science as a vocation: Its past and present Here are several things typical of modern academic performances, whether written or oral. First, there is a display of efforts to get the facts right, to show that matters are indeed as they are said to be. Second, there is an expectation that at least some of those facts are, to a degree, novel, non-obvious, worth pointing out, and that the interpretations or explanations in which the facts are enlisted are plausible, similarly novel, and meriting consideration. -

THE MAN of SCIENCE Steven Shapin

THE IMAGE OF THE MAN OF SCIENCE Steven Shapin The relations between the images of the man of science and the social and cultural realities of scientific roles are both consequential and contingent. Finding out “who the guys were” (to use Sir Lewis Namier’s phrase) does in- deed help to illuminate what kinds of guys they were thought to be, and, for that reason alone, any survey of images is bound to deal – to some extent at least – with what are usually called the realities of social roles.1 At the same time, it must be noted that such social roles are always very substantially con- stituted, sustained, and modified by what members of the culture think is, or should be, characteristic of those who occupy the roles, by precisely whom this is thought, and by what is done on the basis of such thoughts. In socio- logical terms of art, the very notion of a social role implicates a set of norms and typifications – ideals, prescriptions, expectations, and conventions thought properly, or actually, to belong to someone performing an activity of a certain kind. That is to say, images are part of social realities, and the two notions can be distinguished only as a matter of convention. Such conventional distinctions may be useful in certain circumstances. So- cial action – historical and contemporary – very often trades in juxtapositions between image and reality. One might hear it said, for example, that modern American lawyers do not really behave like the high-minded professionals 1 For introductions to pertinent prosopography, see, e.g., Robert M. -

Natural History in the Physician's Study: Jan Swammerdam

BJHS 53(4): 497–525, December 2020. © The Author(s), 2020. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of British Society for the History of Science. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0007087420000436 First published online 29 October 2020 Natural history in the physician’s study: Jan Swammerdam (1637–1680), Steven Blankaart (1650–1705) and the ‘paperwork’ of observing insects SASKIA KLERK* Abstract. While some seventeenth-century scholars promoted natural history as the basis of natural philosophy, they continued to debate how it should be written, about what and by whom. This look into the studios of two Amsterdam physicians, Jan Swammerdam (1637– 80) and Steven Blankaart (1650–1705), explores natural history as a project in the making during the second half of the seventeenth century. Swammerdam and Blankaart approached natural history very differently, with different objectives, and relying on different traditions of handling specimens and organizing knowledge on paper, especially with regard to the way that individual observations might be generalized. These traditions varied from collat- ing individual dissections into histories, writing both general and particular histories of plants and animals, collecting medical observations and applying inductive reasoning. Swammerdam identified the essential changes that insects underwent during their life cycle, described four orders based on these ‘general characteristics’ and presented his findings in specific histories that exemplified the ‘general rule’ of each order. -

Abbildungsverzeichnis

Abbildungsverzeichnis Titelbild: Henry Smeathman: Some Account of the Termites, Which are Found in Africa and Other Hot Climates. In a Letter from Mr. Henry Smeathman, of Clement’s Inn, to Sir Joseph Banks, Bart. P. R. S., in: Philosophical Transac- tions of the Royal Society of London 71 (1781), Tab. VII, S. 193 (Ausschnitt) Abb. 1: Charles Butler: The Feminine Monarchie, or The Historie of Bees. Shewing Their admirable Nature, and Properties, their Generation, and Colonies, Their Government, Loyaltie, Art, Industrie, Enemies, Warres, Magnitani- mies, &c. Together with the right ordering of them from time to time: And the sweet profit arising thereof, London 1623, Frontispiz Abb. 2: Jan Swammerdam: Bibel der Natur, worinnen die Insekten in gewisse Clas- sen vertheilt, sorgfältig beschrieben, zergliedert, in saubern Kupferstichen vorgestellt, mit vielen Anmerkungen über die Seltenheiten der Natur erleutert …, Leipzig 1752, Tafel XIX Abb. 3: Adam Gottlob Schirach: Melitto-Theologia. Die Verherrlichung des glor- würdigen Schöpfers aus der wundervollen Biene, Dresden 1767, Anhang, Tab. IV, Fig. 43 und 44 Abb. 4: Johann Witzgall (Hg.): Das Buch von der Biene, 2. Aufl. Stuttgart 1906, Fig. 55, S. 170 Abb. 5: Thomas Nutt: Humanity to Honey Bees: or, Practical Directions for the Management of Honey-Bees upon an Improved and Humane Plan, 2. Aufl. Wisbech 1834, S. 17 Abb. 6: Johann Witzgall (Hg.): Das Buch von der Biene, 2. Aufl. Stuttgart 1906, Fig. 96, S. 284 Abb. 7: Johann Witzgall (Hg.): Das Buch von der Biene, 2. Aufl. Stuttgart 1906, Fig. 202, S. 320 Abb. 8: Carl Vogt: Untersuchungen über Thierstaaten, Frankfurt a.M. -

Nature's Bible

Nature’s Bible: Insects in Seventeenth-Century European Art and Science Brian W. Ogilvie History Department , University of Massachusetts [email protected] Abstract Keywords: Artists and naturalists in seventeenth-century Europe avidly pursued the study of insects. Natural history, Since entomology had not yet become a distinct discipline, these studies were pursued art, within the framework of natural history, miniature painting, medicine, and anatomy. In Science, the late sixteenth century the Renaissance naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi collected and insects, described individual insects and their lore but showed little sustained interest in their tem - entomology poral transmutations; meanwhile, the court artist Joris Hoefnagel studied the structure of insects in order to paint real and imaginary insects while giving them an emblematic inter - pretation. By the middle of the seventeenth century the painter Johannes Goedaert was assiduously studying insect transformations, which he saw as evidence of God’s wondrous works. His work was critiqued and systematized by the physicians Martin Lister and Jan Swammerdam, who insisted that orderly transformation was the best sign of God’s hand - iwork. These examples show how verbal descriptions and illustrations of insects easily crossed disciplinary boundaries; knowledge generated in one particular context moved into others where it was critiqued but also employed in new investigations. The Bible of Nature; or, The History of Insects appropriate for the study of insects in the Brought into Certain Classes , is the strange seventeenth century. Characterized by title that Jan Swammerdam (d. 1680) gave scholarly erudition, painstaking observa - to his posthumously published magnum tion, and artistic flair, the study of insects opus (Swammerdam 1737-38). -

The Development of Entomology and Insect Collections

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Honors Projects Undergraduate Research and Creative Practice 7-2020 From Aristotle to Wunderkammer: The Development of Entomology and Insect Collections Erica Fischer Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons ScholarWorks Citation Fischer, Erica, "From Aristotle to Wunderkammer: The Development of Entomology and Insect Collections" (2020). Honors Projects. 790. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects/790 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Aristotle to Wunderkammer: The Development of Entomology and Insect Collections Erica Fischer HNR 499: Honors Senior Project 3 April 2017 1 Though much of the emphasis in entomology today is based in economic and applied research in the study of insects, the field first concerned itself in antiquity with research in order to satisfy curiosity and better understand the world. In this work, collections and fieldwork were of paramount importance. The ancient world saw the beginnings of insect classification, as well as efforts in applied natural knowledge. Much of this knowledge was lost by the Medieval period, when entomology was studied in a limited capacity by a few members of the clergy. The early modern period brought the rise of insect collecting associated with status; encyclopedias were the main form of publication for entomological information. With the Victorian era came the professionalization of the biological sciences, including entomology and the delineation of the concept of evolution. -

Science and Natural Language in the Eighteenth Century: Buffon and Linnaeus

Languages of Science in the Eighteenth Century Languages of Science in the Eighteenth Century Edited by Britt-Louise Gunnarsson De Gruyter Mouton An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-3-11-025505-8 e-ISBNBibliografische 978-3-11-025506-5 Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliogra- Libraryfie; detaillierte of Congress bibliografische Cataloging-in-Publication Daten sind im Internet Data über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. Languages of science in the eighteenth century / edited by Britt- ©ISBN 2016Louise 978-3-11-021808-4 Walter Gunnarsson. -

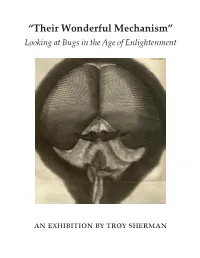

“Their Wonderful Mechanism” Looking at Bugs in the Age of Enlightenment

“Their Wonderful Mechanism” Looking at Bugs in the Age of Enlightenment an exhibition by troy sherman But as mankind became more enlightened, the great wonders of nature in these small animals began to be observed . carolus linnaeus, Fundamenta Entomologiae, 1772 Cover art from robert hooke, Micrographia, 1665 “Their Wonderful Mechanism” Looking at Bugs in the Age of Enlightenment HEN ROBERT HOOKE peered Williams College and organized in three through his microscope into the sections corresponding to the body segments of Weyes of a dronefly, he didn’t simply catch an insect, demonstrates how scientific discourse the bug peering back: concerning bugs he saw his world converged with and reflected in its gaze. helped shape empirical Within each pane of methodologies and the insect’s compound technologies, colonial eyes, wrote Hooke in expansion, and 1666, “I have been able political thought to discover a Land- during western scape of those things Europe’s age of which lay before my Enlightenment. window.” In Hooke’s Hooke’s observa- study, the dronefly’s tion dramatizes the play eyes not only served as between knowledge and experimental material culture at an important to demonstrate the stage in the history of observational capacity entomology: in the 17th of his microscope, and 18th centuries, as but also provided a robert hooke, Micrographia, 1665 European natural philosophers visually captivating turned unprecedented amounts of their metaphor for the new technology. Hooke’s attention towards insect life, bugs in turn experiment indexes a shift of empirical contributed to shaping the new ways that interest towards the study of bugs rooted in these scientists were describing their world. -

The World Pattern of Apicultural Research

ECTD_209 TITLE: The world pattern of apicultural research SOURCE: Journal of Scientific Research. 10 (2): 179-184 DATE: 1985 The Journal of Scientific Research 1985 Vol. 10 : 2 179 Special Lecture Dr. Eva Crane, a world authority on bees and author of over 150 books and papers on beekeeping and research, was currently in Thailand for two weeks as a special guest of Department of Biology and sponsored by British Council. Now she is honorary life President, International Bee Research Association also Scientific Consultant to IBRA Council. • THE WORLD PATTERN OF APICULTURAL RESEARCH Eva Crane International Bee Research Association, Hill House, Gerrards Cross, Bucks. S19 ONR, UK • Discoveries in past centuries One important factor favouring the development of research on bees and their management in a region is a very long tradition of apiculture, so that bees are looked on with favour, and regarded as an interesting subject for study and research. The previous article showed that Europe is such a region, and before 1800 it was the region where studies and discoveries about bees were made, for example: 1568 worker bees can rear a queen from a worker egg (Nikol Jakob, Germany) 1586 the queen is a female and in a colony she is the bee that lays the eggs (Luys Mendez de Torres, Spain) 1609 drones are male (Charles Butler, England) 1625 the first insect (honeybee) drawn under a microscope (Prince Cesi, Italy) 1678-1680 full anatomical drawings of honeybees, using a microscope (Jan Swammerdam, Nether lands) 1684 first correct account of the origin of beeswax (Martin John, Germany) 1739 function of the spiracles discovered (R.A.F. -

Representation of Insects in the Seventeenth Century: a Comparative Approach Domenico Bertoloni Melia a Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA

This article was downloaded by: [Indiana University Libraries] On: 9 November 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 917269096] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Annals of Science Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713692742 The representation of insects in the seventeenth century: a comparative approach Domenico Bertoloni Melia a Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA Online publication date: 15 July 2010 To cite this Article Meli, Domenico Bertoloni(2010) 'The representation of insects in the seventeenth century: a comparative approach', Annals of Science, 67: 3, 405 — 429 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00033790.2010.488920 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00033790.2010.488920 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.