12 Hefner Publishready

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pay-Per-View

Pay-Per-View Don’t bother with the babysitter. Stop worrying about traffic. Because with Pay Per View, you get the best seats in the house without ever leaving home. From UFC fights to exclusive concerts, watch the best in live sports and entertainment right on your own TV. Ordering made easy No need to call or go online. Just order with your remote. From the Guide menu, go to the Pay Per View event channel (PPV) to see what’s playing this month. Once you’ve made your selection, all you need to do is select “Watch” and then confirm your order. It’s that easy. What’s new this month? UFC 242: Khabib vs Poirier September 7th, 2019, 2:00 p.m. ET / 11:00 a.m. PT A classic showdown is expected in Abu Dhabi on September 7, as UFC lightweight champion Khabib Nurmagomedov makes the second defense of his crown against interim 155-pound titlist Dustin Poirier in the main event of UFC 242. Fresh from a submission win over Conor McGregor in the biggest fight of 2018 last October, the unbeaten Nurmagomedov is eager to put his 27-0 record on the line against the veteran Poirier, whose recent winning streak has been highlighted by victories over Max Holloway, Eddie Alvarez, Justin Gaethje and Anthony Pettis. This September, “The Diamond” and “The Eagle” face off for the undisputed lightweight title. SD standard definition $54.99 HD high definition $64.99 Channels 324 and 611 (BlueSky TV SD) Channels 300 and 601 (BlueSky TV HD) Replays: Available until October 5th, 2019 Lucha Libre AAA Wrestling Invades NYC September 15th, 2019, 6:00 p.m. -

Welcome to the 2021 North Shore Diversity Catalog

Salem NORTH SHORE DIVERSITY CATALOG 2021 Welcome to the 2021 North Shore Diversity Catalog T h e Cit i es of S a le m , B ev er ly, Pe a bo dy, and L y nn and t h e To w ns of S w am ps c o t t an d Ma r bl eh ea d p ar t n er ed in Ma r c h 2 021 to la u n ch t h e Nor t h S h or e Div er s i t y C at alo g, a r e gi o na l v e n dor r eg is t r y f or m in or it y- an d w om en - o wn e d b us i n es s e s (MWBE) . T h e Nor t h S h or e is no t o nl y cu lt ur a ll y d iv e r s e, it is h om e to m an y d if f er e nt bus i nes s es r un by p e o pl e wh o hav e ov e r c om e h is t or ic b ar r ie r s , an d we w an t t hem to t h r iv e. T h e Div er s i t y C at a lo g is a m ar ke t i ng t o ol f or b us i n es s e s t h at wis h to of f er t h eir s e r v i ces a n d/o r pr o d uct s to r es id e nt s a nd to o t her bus in es s es a nd institutions w it hi n t h e No r t h S h or e ar ea. -

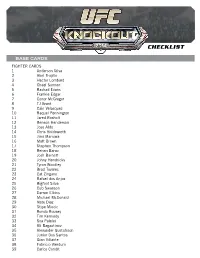

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Villanova University School of Law: Digital Repository Volume 20 Issue 2 Article 4 2013 Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech? The Ultimate Fighting Championship and its Struggle Against the State of New York Over the Message of Mixed Martial Arts Daniel Berger Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Daniel Berger, Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech? The Ultimate Fighting Championship and its Struggle Against the State of New York Over the Message of Mixed Martial Arts, 20 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 381 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol20/iss2/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\20-2\VLS204.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-JUN-13 13:05 Berger: Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech? The Ul Articles CONSTITUTIONAL COMBAT: IS FIGHTING A FORM OF FREE SPEECH? THE ULTIMATE FIGHTING CHAMPIONSHIP AND ITS STRUGGLE AGAINST THE STATE OF NEW YORK OVER THE MESSAGE OF MIXED MARTIAL ARTS DANIEL BERGER* I. INTRODUCTION The promotion-company -

The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport

Journal of Sport Management, 2017, 31, 533-545 https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0333 © 2017 Human Kinetics, Inc. ARTICLE The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport T. Christopher Greenwell University of Louisville Jason M. Simmons University of Cincinnati Meg Hancock and Megan Shreffler University of Louisville Dustin Thorn Xavier University This study utilizes an experimental design to investigate how different presentations (sexualized, neutral, and combat) of female athletes competing in a combat sport such as mixed martial arts, a sport defying traditional gender norms, affect consumers’ attitudes toward the advertising, event, and athlete brand. When the female athlete in the advertisement was in a sexualized presentation, male subjects reported higher attitudes toward the advertisement and the event than the female subjects. Female respondents preferred neutral presentations significantly more than the male respondents. On the one hand, both male and female respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was more attractive and charming than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and more personable than the fighter in the combat ads. On the other hand, respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was less talented, less successful, and less tough than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and less wholesome than the fighter in the neutral ad. Keywords: brand, consumer attitude, sports advertising, women’s sports February 23, 2013, was a historic date for women’s The UFC is not the only MMA organization featur- mixed martial arts (MMA). For the first time in history, ing female fighters. Invicta Fighting Championships (an two female fighters not only competed in an Ultimate all-female MMA organization) and Bellator MMA reg- Fighting Championship (UFC) event, Ronda Rousey and ularly include female bouts on their fight cards. -

Becoming Legendary: Slate Financing and Hollywood Studio Partnership in Contemporary Filmmaking

Kimberly Owczarski Becoming Legendary: Slate Financing and Hollywood Studio Partnership in Contemporary Filmmaking In June 2005, Warner Bros. Pictures announced Are Marshall (2006), and Trick ‘r’ Treat (2006)2— a multi-film co-financing and co-production not a single one grossed more than $75 million agreement with Legendary Pictures, a new total worldwide at the box office. In 2007, though, company backed by $500 million in private 300 was a surprise hit at the box office and secured equity funding from corporate investors including Legendary’s footing in Hollywood (see Table 1 divisions of Bank of America and AIG.1 Slate for a breakdown of Legendary’s performance at financing, which involves an investment in a the box office). Since then, Legendary has been a specified number of studio films ranging from a partner on several high-profile Warner Bros. films mere handful to dozens of pictures, was hardly a including The Dark Knight, Inception, Watchmen, new phenomenon in Hollywood as several studios Clash of the Titans, and The Hangoverand its sequel. had these types of deals in place by 2005. But In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, the sheer size of the Legendary deal—twenty five Legendary founder Thomas Tull likened his films—was certainly ambitious for a nascent firm. company’s involvement in film production to The first film released as part of this deal wasBatman an entrepreneurial endeavor, stating: “We treat Begins (2005), a rebooting of Warner Bros.’ film each film like a start-up.”3 Tull’s equation of franchise. Although Batman Begins had a strong filmmaking with Wall Street investment is performance at the box office ($205 million in particularly apt, as each film poses the potential domestic theaters and $167 million in international for a great windfall or loss just as investing in a theaters), it was not until two years later that the new business enterprise does for stockholders. -

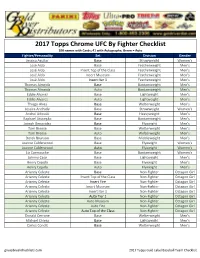

2017 Topps UFC Checklist

2017 Topps Chrome UFC By Fighter Checklist 100 names with Cards; 41 with Autographs; Green = Auto Fighter/Personality Set Division Gender Jessica Aguilar Base Strawweight Women's José Aldo Base Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Top of the Class Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Museum Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Iter 1 Featherweight Men's Thomas Almeida Base Bantamweight Men's Thomas Almeida Auto Bantamweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Base Lightweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Auto Lightweight Men's Thiago Alves Base Welterweight Men's Jessica Andrade Base Strawweight Women's Andrei Arlovski Base Heavyweight Men's Raphael Assunção Base Bantamweight Men's Joseph Benavidez Base Flyweight Men's Tom Breese Base Welterweight Men's Tom Breese Auto Welterweight Men's Derek Brunson Base Middleweight Men's Joanne Calderwood Base Flyweight Women's Joanne Calderwood Auto Flyweight Women's Liz Carmouche Base Bantamweight Women's Johnny Case Base Lightweight Men's Henry Cejudo Base Flyweight Men's Henry Cejudo Auto Flyweight Men's Arianny Celeste Base Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Iter 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Tier 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Donald Cerrone Base Welterweight -

Ufc Fight Night Features Exciting Middleweight Bout

® UFC FIGHT NIGHT FEATURES EXCITING MIDDLEWEIGHT BOUT ® AND THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER FINALE ON FOX SPORTS 1 APRIL 16 Two-Hour Premiere of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER: TEAM EDGAR VS. TEAM PENN Follows Fights on FOX Sports 1 LOS ANGELES, CA – Two seasons of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER® converge on FOX Sports 1 on Wednesday, April 16, when UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: BISPING VS. KENNEDY features THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER NATIONS welterweight and middleweight finals, the coaches’ fight and an exciting headliner between No. 5-ranked middleweight Michael Bisping (25-5) and No. 8- ranked Tim Kennedy (17-4). FOX Sports 1 carries the preliminary bouts beginning at 5:00 PM ET, followed by the main card at 7:00 PM ET from Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. Immediately following UFC FIGHT NIGHT: BISPING VS. KENNEDY is the two-hour season premiere of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER®: TEAM EDGAR vs. TEAM PENN (10:00 PM ET), highlighting 16 middleweights and 16 light heavyweights battling for a spot on the team of either former lightweight champion Frankie Edgar or two-division champion BJ Penn. UFC on FOX analyst Brian Stann believes the headliner between Bisping and Kennedy is a toss-up. “Kennedy has one of the best top games in mixed martial arts and he’s showcased his knockout power in his last fight against Rafael Natal. Bisping is one of the best all-around mixed martial artists in the middleweight division. Every time people start to count him out, he comes in and wins fights.” In addition to the main event between Bisping and Kennedy, UFC FIGHT NIGHT consists of 12 more thrilling matchups including THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER NATIONS Team Canada coach Patrick Cote (20-8) and Team Australia coach Kyle Noke (20-6-1) in an exciting welterweight bout. -

Cultivating Identity and the Music of Ultimate Fighting

CULIVATING IDENTITY AND THE MUSIC OF ULTIMATE FIGHTING Luke R Davis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Megan Rancier, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2012 Luke R Davis All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Megan Rancier, Advisor In this project, I studied the music used in Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) events and connect it to greater themes and aspects of social study. By examining the events of the UFC and how music is used, I focussed primarily on three issues that create a multi-layered understanding of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) fighters and the cultivation of identity. First, I examined ideas of identity formation and cultivation. Since each fighter in UFC events enters his fight to a specific, and self-chosen, musical piece, different aspects of identity including race, political views, gender ideologies, and class are outwardly projected to fans and other fighters with the choice of entrance music. This type of musical representation of identity has been discussed (although not always in relation to sports) in works by past scholars (Kun, 2005; Hamera, 2005; Garrett, 2008; Burton, 2010; Mcleod, 2011). Second, after establishing a deeper sense of socio-cultural fighter identity through entrance music, this project examined ideas of nationalism within the UFC. Although traces of nationalism fall within the purview of entrance music and identity, the UFC aids in the nationalistic representations of their fighters by utilizing different tactics of marketing and fighter branding. Lastly, this project built upon the above- mentioned issues of identity and nationality to appropriately discuss aspects of how the UFC attempts to depict fighter character to create a “good vs. -

UFC Fight Night: Dos Anjos Vs

UFC Fight Night: Dos Anjos vs. Alvarez Live Main Card Highlights UFC 200 Fight Week Coverage on Fight Network Toronto – Fight Network, the world’s premier 24/7 multi- platform channel dedicated to complete coverage of combat sports, today announced extensive live coverage for UFC International Fight Week™ in Las Vegas, the biggest week in UFC history, highlighted by a live broadcast of the main card for UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: DOS ANJOS vs. ALVAREZ from the MGM Grand Garden Arena on Thursday, July 7 at 10 p.m. ET, plus the live prelims for THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER FINALE®: Team Joanna vs. Team Claudia on Friday, July 8 at 8 p.m. ET. Fight Network will air the live UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: DOS ANJOS vs. ALVAREZ main card across Canada on July 7 at 10 p.m. ET, preceded by a live Pre-Show at 9 p.m. ET. In the main event, dominant UFC lightweight champion Rafael dos Anjos (24-7) puts his championship on the line in a five- round barnburner against top contender Eddie Alvarez (27-4). In other featured bouts, Roy “Big Country” Nelson (22-12) throws down with Derrick “The Black Beast” Lewis (15-4, 1NC) in an explosive heavyweight collision, Alan Jouban (13-4) takes on undefeated Belal Muhammad (9-0) in a welterweight affair, plus “Irish” Joe Duffy (14-2) welcomes Canada’s Mitch “Danger Zone” Clarke (11-3) back to action in a lightweight matchup. Live fight week coverage begins on Wednesday, July 6 at 2 p.m. ET with a live presentation of the final UFC 200 pre-fight press conference, featuring UFC president Dana White and main card superstars Jon Jones, Daniel Cormier, Brock Lesnar, Mark Hunt, Miesha Tate, Amanda Nunes, Jose Aldo and Frankie Edgar. -

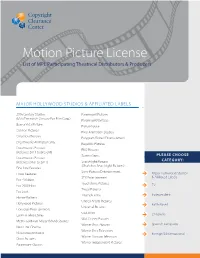

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS 20th Century Studios Paramount Pictures (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) Paramount Vantage Buena Vista Pictures Picturehouse Cannon Pictures Pixar Animation Studios Columbia Pictures Polygram Filmed Entertainment Dreamworks Animation SKG Republic Pictures Dreamworks Pictures RKO Pictures (Releases 2011 to present) Screen Gems PLEASE CHOOSE Dreamworks Pictures CATEGORY: (Releases prior to 2011) Searchlight Pictures (f/ka/a Fox Searchlight Pictures) Fine Line Features Sony Pictures Entertainment Focus Features Major Hollywood Studios STX Entertainment & Affiliated Labels Fox - Walden Touchstone Pictures Fox 2000 Films TV Tristar Pictures Fox Look Triumph Films Independent Hanna-Barbera United Artists Pictures Hollywood Pictures Faith-Based Universal Pictures Lionsgate Entertainment USA Films Lorimar Telepictures Children’s Walt Disney Pictures Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios Warner Bros. Pictures Spanish Language New Line Cinema Warner Bros. Television Nickelodeon Movies Foreign & International Warner Horizon Television Orion Pictures Warner Independent Pictures Paramount Classics TV 41 Entertaiment LLC Ditial Lifestyle Studios A&E Networks Productions DIY Netowrk Productions Abso Lutely Productions East West Documentaries Ltd Agatha Christie Productions Elle Driver Al Dakheel Inc Emporium Productions Alcon Television Endor Productions All-In-Production Gmbh Fabrik Entertainment Ambi Exclusive Acquisitions -

Are Ufc Fighters Employees Or Independent Contractors?

Conklin Book Proof (Do Not Delete) 4/27/20 8:42 PM TWO CLASSIFICATIONS ENTER, ONE CLASSIFICATION LEAVES: ARE UFC FIGHTERS EMPLOYEES OR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS? MICHAEL CONKLIN* I. INTRODUCTION The fighters who compete in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (“UFC”) are currently classified as independent contractors. However, this classification appears to contradict the level of control that the UFC exerts over its fighters. This independent contractor classification severely limits the fighters’ benefits, workplace protections, and ability to unionize. Furthermore, the friendship between UFC’s brash president Dana White and President Donald Trump—who is responsible for making appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”)—has added a new twist to this issue.1 An attorney representing a former UFC fighter claimed this friendship resulted in a biased NLRB determination in their case.2 This article provides a detailed examination of the relationship between the UFC and its fighters, the relevance of worker classifications, and the case law involving workers in related fields. Finally, it performs an analysis of the proper classification of UFC fighters using the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) Twenty-Factor Test. II. UFC BACKGROUND The UFC is the world’s leading mixed martial arts (“MMA”) promotion. MMA is a one-on-one combat sport that combines elements of different martial arts such as boxing, judo, wrestling, jiu-jitsu, and karate. UFC bouts always take place in the trademarked Octagon, which is an eight-sided cage.3 The first UFC event was held in 1993 and had limited rules and limited fighter protections as compared to the modern-day events.4 UFC 15 was promoted as “deadly” and an event “where anything can happen and probably will.”6 The brutality of the early UFC events led to Senator John * Powell Endowed Professor of Business Law, Angelo State University.