Glycaemic and Insulin Index of Four Common German Breads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd Thesis (PDF, 6.88MB)

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright APPENDIX Clinical Application of the Food Insulin Index to Diabetes Mellitus Kirstine Bell B.Nutr&Diet (Hons), GradCertDiabEd (Dist) Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 5 September 2014 Appendix Table of Contents Section 1: Carbohydrate Counting Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Appendix 1: Published journal article -

FOOD CARBS and ARTIFICIAL PANCREAS Last Year's Research Project Focused on Perception of Sweetness and Its Relationship to Glucose and Food Processing

FOOD CARBS AND ARTIFICIAL PANCREAS Last year's research project focused on perception of sweetness and its relationship to glucose and food processing. In this year's project, new questions were raised with emphasis on a diabetic diet and diabetes treatment by means of an artificial pancreas. The project had two parts. In its science part, in addition to glucose, the concentration of sucrose and lactose were measured in 6 solid, 6 viscous and 6 liquid foods; the concentration of fructose was researched. The 2021 science project methodology was built on 2020 project based on measuring glucose % by using URS-1G test strips; color change after 30 sec was matched to controls. Controls were made by using glucose dilutions to create 2%, 1%, 0.5%, 0.25%, 0.125%, and 0.0625% concentrations; water was 0%. It was expanded; it involved testing invertase and lactase activity and determining glucose linear time point in order to measure sucrose and lactose concentrations. The foods' Glycemic Index, Glycemic Load, Insulin Index and Carb Factor were examined; their meaning in diabetic diet was discussed. In the engineering part, an artificial pancreas model, a device of continuous sensor providing the information to auto-correcting pump how much chemical (insulin) should be given, was created. The engineering part involved assembling the electrical circuit on the breadboard, making the conductivity sensor and then testing the artificial pancreas model by applying the concept of acid/base chemistry and an electrical circuit. FOOD CARBS AND ARTIFICIAL PANCREAS TABLE OF CONTENT Introduction Review of Literature Methodology. Part I: Food Carbs Methodology. -

Comparison of Carbohydrate Counting and Food

Official Title of the study: Comparison of Carbohydrate Counting and Food Insulin Index Methods in the Determination of Insulin Doses for High-and Low-Glycemic Index Meals in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes NCT number: Document Date:21 November 2018 (The date on which the uploaded document was approved by a human subjects protection review board.) 1. Background Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease characterized by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from an absolute endogenous insulin deficiency. In type 1 diabetes management, premeal insulin dosage and physiological insulin requireme0nt must be matched to maintain optimal blood glucose control (1). Intensive insulin therapy is the preferred treatment for individuals with type 1 diabetes. It can be an effective way of controlling blood glucose levels and minimising the risk of long term diabetic complications (2, 3). Insulin delivery is achieved subcutaneously using multiple daily injections or subcutaneous insulin infusion using insulin pumps. It provides the calculation of insulin doses according to the carbohydrate content of the meal and pre-meal blood glucose levels. It can also provide a less restricted lifestyle to individuals with type 1 diabetes by providing flexibility in meal time, quantity and frequency (4, 5). Achieving glycemic control is important for patients with diabetes because it effects the development of diabetic complications. Diabetes control is mainly assessed according to HbA1c, fasting blood glucose and blood glucose measured two hours after meal consumption. In the control of type 1 diabetes, not only regular use of insulin is sufficient, but also important in balanced diet and regular physical activity. An individualized diet plan in particular is the corner-stone to proper metabolic control (6). -

A Comparison of the Glycemic Index (Gi) Results Obtained from Two Techniques on a Group of Healthy and a Group of Mixed Subjects

A COMPARISON OF THE GLYCEMIC INDEX (GI) RESULTS OBTAINED FROM TWO TECHNIQUES ON A GROUP OF HEALTHY AND A GROUP OF MIXED SUBJECTS by Elizabeth Delport Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the MAGISTER IN DIETETICS in the FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA PRETORIA MAY 2006 Promoter: GJ Gericke ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following persons from the bottom of my heart: The Lord without Whom this research would not have been completed Ms Gerda J Gericke for your valuable guidance and support throughout the duration of the study Prof HT Groeneveld for your guidance in and statistical processing of the data Sam Mawson and Michelle van den Berg for your invaluable technical assistance Anne and Pete Grantham for perusing the document for grammatical correctness Dr Mark Wickham and his team of medical technologists at Du Buisson and Partners Pathologists - for the generous sponsorship and friendly assistance during part one of the study Pioneer Food Group and specifically Bokomo Breakfast Foods, Ceres Fruit Juices and Sasko Milling and Baking for your generous sponsorship of the study Novo Nordisk for your handsome sponsorship of the study All the test subjects for your sacrifice, diligence and selfless testing during part one and two of the study Elizabeth Combrink and Marinda Venter, my partners at our consulting rooms, for standing in for me so often during all the times I had to take study leave My husband, children, parents and friends for your prayers, encouragement and support during the course of the study i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract Page List of Tables vi List of Figures viii List of Addenda xi List of Abbreviations xii Abstract xiii 1. -

The Food Insulin Index Be Used to Predict Mealtime Insulin Requirements in Type 1 Diabetes? FII Improves Postprandial Glycaemic Control

Optimising Mealtime Insulin Dosing: Do Protein & Fat Matter? Dr Kirstine Bell APD, CDE & PhD “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted” Albert Einstein Overview Carbohydrate Counting Effects of Protein & Fat Clinical Application Food Insulin Index (FII) Estimating Mealtime Insulin Dose in Type 1 Diabetes Carbohydrate Counting Glycaemic Response Bolus Insulin Dose Limitations of Carb Counting Carbohydrates don’t affect blood glucose levels equally (Glycemic Index) Evidence for the efficacy of carbohydrate counting is limited Carbohydrate Counting Does Not Significantly Improve HbA1c Overall change in HbA1c -0.35% points (p = 0.096) Bell et al, Lancet Diab & Endo 2014; 2(2): 133- 140 Limitations of Carb Counting Carbohydrates don’t affect blood glucose levels equally (Glycemic Index) Evidence for the efficacy of carbohydrate counting is limited Treating Symptoms vs. Cause Stimulation of insulin secretion is multifactorial Do Protein and Fat Affect Blood Glucose Levels? Healthy Subjects Insulin is an anabolic hormone, involved in the storage of glucose, amino acids and fatty acids Minimal effect on BG in healthy subjects Protein can cause a significant insulin response Fat in isolation does not initiate insulin release but amplifies glucose-stimulated insulin release Fat also increases insulin resistance Type 1 Diabetes Normal BGL Elevated BGL Insulin Insulin Meal Meal • Increased hepatic glucose output • Insulin resistance Fat and Protein Increase Insulin Requirements Fat & Protein (HF/HP) Fat (HF/LP) Protein (LF/HP) CHO (LF/LP) Smart et al. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 3897- 3902 Pure Protein Increases BG Paterson et al. Diabetes 2014;63(S1):A15 Dietary Fat Increases BGL and Insulin Requirements High Fat vs Low Fat Dinner on postprandial BGL using closed loop insulin delivery Wolpert et al. -

Studies on the Glycemic Index of Raisins and on the Intestinal

ABSTRACT The glycemic index (GI) measures the magnitude of the postprandial increase in blood glucose caused by a test food compared with a reference food/beverage, such as a glucose solution or white bread, containing the same amount of carbohydrate. The insulin index is determined in a similar manner of GI calculation, except that blood insulin AUC is used in place of blood glucose AUC. Low GI and insulin index foods are desirable because foods with low GI and insulin index result in gradual increase in postprandial glycemia/insulinemia and lower blood glucose/insulin fluctuations compared with foods with high GI and insulin index. This attenuated glycemic and insulinemic responses of low GI and insulin index foods is associated with reduced risks of obesity, diabetes mellitus, and chronic diseases. Fructose has low glycemic and insulin index, and a high fructose-containing food, such as raisins, would be expected to have low glycemic and insulin index values. In addition to its low glycemic and insulin index, small, or “catalytic” amounts of fructose (e.g., 5- 10 g) lower the glycemic response to other carbohydrates. However, prefeeding of fructose is necessary to achieve this effect due to the slow intestinal absorption of fructose. The overall objective of this dissertation was to investigate the current interest of carbohydrate metabolism. The first goal was to determine a difference in carbohydrate iii metabolism in populations with different metabolic status. The second objective was to determine fructose absorption in the presence of erythritol in vivo and in vitro. The GI and insulin index of raisins were determined and compared in healthy sedentary young adults, endurance athletes, and people with impaired glucose tolerance. -

4 Healthy Cereals That Make You

JOEL MARION & TIM SKWIAT 2 4 “HEALTHY” CEREALS THAT MAKE YOU FAT! If you were to poll a group of people and ask them what they believed composed a “healthy” breakfast, it’s likely that the majority would paint a picture that looked something like the following: While there’s quite a bit that could potentially be discussed regarding just exactly how “healthy” that breakfast is, the fact of the matter is that breakfast cereal is commonly thought of as a very healthy breakfast—and snack—option. You’re certainly in the majority if breakfast cereal is a staple in your house and pantry. The vast majority of us have been told—by our parents, doctors, marketers, and more— that cereals are a healthy component of a balanced breakfast. What’s more, if you take a stroll down the cereal aisle at the grocery store, you’ll be reminded how these boxes with colorful, attractive packaging are “heart healthy,” made with whole grains, filled with vitamins and minerals, and more. Even more, many of our favorite cartoon characters, role models, and iconic athletes have graced the packaging of the boxes of this breakfast table staple. If they’re doing it, then it must be good, right? Not so fast. 3 If you’re someone who typically considers cereal a healthy option to help you lose weight, then you could very well be holding yourself back from optimizing your fat loss. Worse yet, these very food choices may be making you fatter! Starting Your Day on the Wrong Foot Simply put, breakfast cereals are carbohydrate-dense and do very little to promote a fat-burning environment. -

Dietary Insulin Index and Insulin Load in Relation to Endometrial Cancer Risk in the Nurses' Health Study

Published OnlineFirst May 23, 2014; DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0157 Cancer Epidemiology, Research Article Biomarkers & Prevention Dietary Insulin Index and Insulin Load in Relation to Endometrial Cancer Risk in the Nurses' Health Study Jennifer Prescott1,3, Ying Bao1, Akila N. Viswanathan2, Edward L. Giovannucci1,4, Susan E. Hankinson1,5, and Immaculata De Vivo1,3 Abstract Background: Although unopposed estrogen exposure is considered the main driver of endometrial carcinogenesis, factors associated with states of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are independently associated with endometrial cancer risk. We used dietary insulin load and insulin index scores to represent the estimated insulin demand of overall diets and assessed their association with endometrial cancer risk in the prospective Nurses’ Health Study. Methods: We estimated incidence rate ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for risk of invasive endometrial cancer using Cox proportional hazards models. Between the baseline dietary questionnaire (1980) and 2010, we identified a total of 798 incident-invasive epithelial endometrial adenocarcinomas over 1,417,167 person-years of follow-up. Results: Dietary insulin scores were not associated with overall risk of endometrial cancer. Comparing women in the highest with the lowest quintile, the multivariable-adjusted RRs of endometrial cancer were 1.07 (95% CI, 0.84–1.35) for cumulative average dietary insulin load and 1.03 (95% CI, 0.82–1.31) for cumulative average dietary insulin index. Findings did not vary substantially by alcohol consumption, total dietary fiber P intake, or body mass index and/or physical activity ( heterogeneity 0.10). Conclusions: Intake of a diet predicted to stimulate a high postprandial insulin response was not associated with endometrial cancer risk in this large prospective study. -

The Glycaemic Index and Insulinaemic Index of Commercially Available Breakfast and Snack Foods in an Asian Population

Downloaded from British Journal of Nutrition (2018), 119, 1151–1156 doi:10.1017/S0007114518000703 © The Authors 2018 https://www.cambridge.org/core The glycaemic index and insulinaemic index of commercially available breakfast and snack foods in an Asian population Wei Shuan Kimberly Tan1, Wei Jie Kevin Tan1, Shalini D/O Ponnalagu1, Katie Koecher2, Ravi Menon2, . IP address: Sze-Yen Tan1 and Christiani J. Henry1,3* 1Clinical Nutrition Research Centre (CNRC), Singapore Institute for Clinical Sciences (SICS), Agency for Science, Technology 170.106.40.40 and Research (A*STAR) and National University Health System, 117599 Singapore 2General Mills, Inc., Golden Valley, MN 55427, USA 3Department of Biochemistry, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, 117597 Singapore , on – – (Submitted 29 November 2017 Final revision received 26 January 2018 Accepted 23 February 2018) 25 Sep 2021 at 12:23:36 Abstract A low-glycaemic-index (GI) breakfast has been shown to lower blood glucose levels throughout the day. A wide variety of breakfast foods are consumed, but their GI values are largely unknown, hence limiting consumers’ ability to select healthier options. This study investigated the GI values of ten common breakfast (five Asian and five Western) foods in this region using a randomised, cross-over study design. Participants , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at arrived after an overnight fast, and fasting blood sample was taken before participants consumed test foods. Next, blood samples were taken at fixed intervals for 180 min. Glycaemic and insulinaemic responses to test foods were calculated as incremental AUC over 120 min, which were subsequently reported as glycaemic and insulinaemic indices. -

A Preliminary Assessment of the Glycemic Index of Honey

A Preliminary Assessment of the Glycemic Index of Honey A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation by Dr Jayashree Arcot and Prof Jennie Brand-Miller March 2005 RIRDC Publication No 05/027 RIRDC Project No UNS-17A © 2005 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 1 74151 126 7 ISSN 1440-6845 A preliminary assessment of the Glycemic Index of honey Publication No. 05/027 Project No. UNS-17A The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable industries. The information should not be relied upon for the purpose of a particular matter. Specialist and/or appropriate legal advice should be obtained before any action or decision is taken on the basis of any material in this document. The Commonwealth of Australia, Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, the authors or contributors do not assume liability of any kind whatsoever resulting from any person's use or reliance upon the content of this document. This publication is copyright. However, RIRDC encourages wide dissemination of its research, providing the Corporation is clearly acknowledged. For any other enquiries concerning reproduction, contact the Publications Manager on phone 02 6272 3186. Researcher Contact Details Dr. Jayashree Arcot Prof. Jennie Brand Miller Department of Food Science and Technology Human Nutrition Unit University of New South Wales University of Sydney Phone: 02 9385 5360 Phone: 02 9351 3759 Fax: 02 9385 5931 Fax: 02 9351 6022 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] In submitting this report, the researcher has agreed to RIRDC publishing this material in its edited form. -

The Influence of the Subjects' Training State on the Glycemic Index

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2007) 61, 19–24 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0954-3007/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/ejcn ORIGINAL ARTICLE The influence of the subjects’ training state on the glycemic index S Mettler, F Lamprecht-Rusca, N Stoffel-Kurt, C Wenk and PC Colombani Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Objective: To determine the glycemic index (GI) dependence on the training state of healthy adult males. Subjects and design: Young, adult males of normal body mass index and normal glucose tolerance were tested twice with a 50 g reference glucose solution and twice with a breakfast cereal containing 50 g of available carbohydrates in a randomized order. Ten subjects were sedentary (SE), 12 were moderately trained (MT) and 12 were endurance trained (ET). Blood glucose, insulin and glucagon were measured. Results: The GI differed significantly between SE and ET subjects (P ¼ 0.02, mean difference: 23 GI units, 95% CI ¼ 3–42 GI units). The GI of the MT subjects was intermediary, but did not differ significantly from the SE or ET subjects. The insulin index did not differ significantly between the groups (P ¼ 0.65). Conclusion: The GI of the commercially available breakfast cereal depended on the training state of the healthy males. The training state is the first reported factor influencing the GI that is subject specific rather than food specific. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2007) 61, 19–24. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602480; published online 12 July 2006 Keywords: carbohydrates; glucose; exercise; glycemic index; insulin; insulinemic index Introduction or absolute glycemic response (Wolever et al., 2003). -

Glycemic Index & Glycemic Load

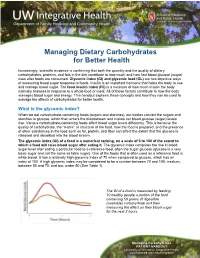

Managing Dietary Carbohydrates for Better Health Increasingly, scientific evidence is confirming that both the quantity and the quality of dietary carbohydrates, proteins, and fats in the diet contribute to how much and how fast blood glucose (sugar) rises after foods are consumed. Glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL) are two objective ways of measuring blood sugar response to foods. Insulin is an important hormone that helps the body to use and manage blood sugar. The food insulin index (FII) is a measure of how much insulin the body normally releases in response to a whole food or meal. All of these factors contribute to how the body manages blood sugar and energy. This handout explains these concepts and how they can be used to manage the effects of carbohydrates for better health. What is the glycemic index? When we eat carbohydrate-containing foods (sugars and starches), our bodies convert the sugars and starches to glucose, which then enters the bloodstream and makes our blood glucose (sugar) levels rise. Various carbohydrate-containing foods affect blood sugar levels differently. This is because the quality of carbohydrate, the “matrix” or structure of the food, how the food is prepared, and the presence of other substances in the food such as fat, protein, and fiber can affect the extent that the glucose is released and absorbed into the blood stream. The glycemic index (GI) of a food is a numerical ranking, on a scale of 0 to 100 of the extent to which a food will raise blood sugar after eating it. The glycemic index compares the rise in blood sugar level after eating a particular food to a reference food, often the sugar glucose (glucose is a very basic sugar and not the same as table sugar).