CA Profile Report 2.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Savelugu-Nanton Municipal Assembly 2

Table of Contents PART A: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 1. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE MUNICIPAL .................................................................. 4 2. POPULATION STRUCTURE ......................................................................................... 4 3. MUNICIPAL ECONOMY ................................................................................................ 4 a. AGRICULTURE ............................................................................................................ 4 REPUBLIC OF GHANA b. MARKET CENTRE ...................................................................................................... 7 c. ROAD NETWORK ........................................................................................................ 7 COMPOSITE BUDGET d. EDUCATION ................................................................................................................. 8 e. HEALTH ......................................................................................................................... 8 FOR 2018-2021 f. WATER AND SANITATION ....................................................................................... 9 g. ENERGY ....................................................................................................................... 10 PROGRAMME BASED BUDGET ESTIMATES 4. VISION OF THE MUNICIPAL ASSEMBLY .............................................................. 10 5. MISSION -

FAILING STATE-INTERVENTIONS and WITCH-HUNTS in GHANA Felix Riedel, Phd Anthropologist

TWO „RESETTLED“ WOMEN FROM BANYASI, FOUND 200 KM AWAY IN TINDANG, ANOTHER CAMP FOR WITCH-HUNT VICTIMS. FAILING STATE-INTERVENTIONS AND WITCH-HUNTS IN GHANA Felix Riedel, PhD Anthropologist For twenty years Ghanaian state agencies have been announcing the closure of the so- called “witches camps”. A recent resettlement-campaign led by MOWAC and the NGO ActionAid Ghana has aggravated the problem and exploited victims emotionally in a staged mass-resettlement. In Ghana, state-run “resettlements” have failed initially and are only slowly modified. Through former actions, traumatized victims of violence were put under permanent stress and fear. This report seeks to contribute to a better understanding of a best practice for and with witch-hunt victims. CLOSURE, FRAUD SUMMARY OF THE AND TRAUMA CAMPS THE MALTREATMENT OF WITCH- There are 10 sanctuaries for witch- HUNT VICTIMS IN NORTHERN hunt Victims in GHANA Northern Ghana: - Gambaga SUMMARY - Gushiegu The government of Ghana and ActionAid, a multinational NGO claimed in late 2014 to have resettled large numbers of victims accused of - Gbintiri witchcraft. Fact finding missions in early 2015 and late 2016 as well as - Nabule testimonies with reliable and hardened experts in the field have clearly disproved such claims. Victims and experts in the camps denied - Gushiegu Ghetto presence or efforts by governmental institutions, statistics had not shown a reduction. The advertised resettlement exercise of 50 women, - Gushiegu Town the “closure of the Banyasi camp” turned out to be entirely staged for - Kpatinga the media. Only recently and due to the diplomatic efforts of the Witch- hunt Victims Empowerment Project (WHVEP) and the Gambaga - Tindang/Gnani Outcast-Home Project (GO-Home-Project), state-actors seem to be adjusting their strategies, 1 without admitting former failures. -

RESILIENCY in NORTHERN GHANA (RING) QUARTERLY REPORT FY 2018 (October 1, 2017 – December 31, 2017) Contract No

January 30, 2018 Revised April 6, 2018 GenGene RESILIENCY IN NORTHERN GHANA (RING) QUARTERLY REPORT FY 2018 (October 1, 2017 – December 31, 2017) Contract No. AID-641-C-14-00002 January 30, 2018 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Global Communities. January 30, 2018 Revised April 6, 2018 USAID RESILIENCY IN NORTHERN GHANA (RING) QUARTERLY REPORT FY 2018 Q1 (October 1, 2017 – December 31, 2017) DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. January 30, 2018 Revised April 6, 2018 Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ...................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 7 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 2. Administration and Finance .................................................................................................. 9 Grants and Contracts................................................................................................... 9 Human Resources ....................................................................................................... 9 3. Regional Partner Coordination and Support ........................................................................10 -

A History of German Presence in Nawuriland, Ghana

African Studies Centre Leiden, The Netherlands Gyama Bugibugi (German gunpowder): A history of German presence in Nawuriland, Ghana Samuel Aniegye Ntewusu ASC Working Paper 133 / 2016 African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands Telephone +31-71-5273372 E-mail [email protected] Website www.ascleiden.nl © Samuel Aniegye Ntewusu, 2016 GYAMA BUGIBUGI (German Gunpowder): A HISTORY OF GERMAN PRESENCE IN NAWURILAND, GHANA Abstract This paper discusses general political and economic issues in Nawuriland during and after German colonialism. The paper argues that the legacies of German colonialism are still largely seen and felt in Nawuriland especially in plantation projects, land and chieftaincy. Introduction The Nawuri are part of the larger Guan group in Ghana. Guans are believed to be the first settlers in modern day Ghana. They are scattered across eight of the ten regions in Ghana- namely Greater Accra, Ashanti, Eastern, Brong Ahafo, Volta, Northern, Western and Central regions. Guans speak distinct languages that are different from the major languages in Ghana examples of which include the Ga-Dangbe, Akan and Ewe. Guans in the Volta Region include Kraakye/Krachi, Akpafu/Lolobi, Buem, Nkonya, Likpe, Logba and Anum-Boso. In the central region there are the Effutu, Awutu and Senya in Winneba and Bawjiase. One finds Larteh, Anum, Mamfi and Kyerepong in the Eastern region. The Gonja, Nawuri, Nchumburu and Mpre people in the Northern and Brong Ahafo regions. Some indigenes of Kpeshie in Greater Accra also claim Guan ancestry.1 Geographically, the Nawuri are located in the North-Eastern part of Ghana. They are about 461kms away from Accra, the capital of Ghana. -

Wulensi Workshop Report

Participatory Assessment of Development http://www.padev.nl WULENSI WORKSHOP REPORT by Richard W. Nartey Yeboah PADev Working Paper No. W.2011.2 Participatory Assessment of Development WULENSI WORKSHOP REPORT by Richard W. Nartey Yeboah PADev Working Paper No. W.2011.2 December 2011 This working paper is part of series of papers reporting on a participatory and holistic evaluation of development initiatives in Northern Ghana and Burkina Faso, organised in the framework of the ‘Participatory Assessment of Development’ project. In this project the following organization are involved: the University of Amsterdam (UvA), the University for Development Studies (UDS, Ghana), Expertise pour le Développement du Sahel (EDS, Burkina Faso), ICCO, Woord en Daad, Prisma, the African Studies Centre (ASC) and the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT). The workshop in Wulensi took place from 18 to 20 January 2010. The methodology is described in detail in the PADev Guidebook by Dietz et al (2011). The guidebook and more information about this project is available at http://www.padev.nl . Author’s contact: [email protected] Other contributors: Ton Dietz (overall PADev team leader), Anika Altaf, Genevieve Audet-Bélanger, Frederick D. Bebelleh, Adama Bélemvire (PADev team leader Burkina Faso), Sanne Böhmer, Samuel Z. Bonye, Roger Bymolt, Saa Dittoh, Kees van der Geest, Dieneke de Groot, Christiana Kangsangbata, Agnieszka Kazimierczuk, Martha Lahai, Akudugu A. Mamudu, Aurélien Marsais, David Millar, Francis Obeng (PADev team leader Ghana), Jerim Obure, Jolien Oosterheerd, Nicky Pouw, Wouter Rijneveld, Richard Yeboah Nartey, Conrad A. Weobong, Fred Zaal and Ziba. Reference to this report: Yeboah, R. W. N. (2011). Participatory Assessment of Development: Wulensi Workshop Report, PADev Working Paper W.2011.2. -

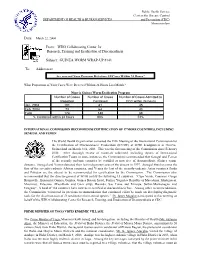

GUINEA WORM WRAP-UP #141 To

Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES and Prevention (CDC) Memorandum Date: March 22, 2004 From: WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis Subject: GUINEA WORM WRAP-UP #141 To: Addressees Are you and Your Program Detecting All Cases Within 24 Hours? What Proportion of Your Cases Were Detected Within 24 Hours Last Month? Nigeria Guinea Worm Eradication Program Number of Cases Number of Cases Number of Cases Admitted to Reported Contained CCC within 24 hours Jan. 2004 101 81 45 Feb. 2004 73 64 43 Total 174 145 88 % Contained within 24 hours 83% 51% INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION RECOMMENDS CERTIFICATION OF 17 MORE COUNTRIES, INCLUDING SENEGAL AND YEMEN The World Health Organization convened the Fifth Meeting of the International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication (ICCDE) at WHO headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland on March 9-11, 2004. This was the first meeting of the Commission since February 2000. After thorough review of materials submitted, including reports of International Certification Teams in some instances, the Commission recommended that Senegal and Yemen of the recently endemic countries be certified as now free of dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease). Senegal and Yemen detected their last indigenous cases of the disease in 1997. Senegal thus becomes the first of the recently-endemic African countries, and Yemen the last of the recently-endemic Asian countries (India and Pakistan are the others) to be recommended for certification by the Commission. The Commission also recommended that the director-general of WHO certify the following 15 countries: “Cape Verde, Comoros, Congo Brazzaville, Equatorial Guinea, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Israel, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Madagascar, Mauritius, Palestine (West-Bank and Gaza strip), Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Serbia-Montenegro, and Uruguay”. -

Composite Budget for 2020-2023 Programme Based

Table of Contents PART A: STRATEGIC OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................ 3 1. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE DISTRICT ......................................................................................... 3 2. POPULATION STRUCTURE ........................................................................................................... 3 3. VISION ................................................................................................................................................. 3 4. MISSION .............................................................................................................................................. 3 REPUBLIC OF GHANA 5. GOALS ................................................................................................................................................ 3 6. CORE FUNCTIONS ........................................................................................................................... 4 7. DISTRICT ECONOMY ...................................................................................................................... 5 COMPOSITE BUDGET 8. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS IN 2019 ...................................................................................................... 7 9. REVENUE AND EXPENDITURE PERFORMANCE .................................................................. 11 a. REVENUE ........................................................................................................................................ -

Establishing an Index Insurance Trigger for Crop Loss in Northern Ghana

ESTABLISHLISING AN IINDEXNDEX INSURANCE TRIGGERS FOR CROP LOSS IN NORTHERN GHANA The Katie School of Insurance RESEARCH P A P E R N o . 7 SEPTEMBER 2011 ESTABLISHING AN INDEX of income for 60 percent of the population. INSURANCE TRIGGER FOR CROP Agricultural production depends on a number of LOSS IN NORTHERN GHANA factors including economic, political, technological, as well as factors such as disease, fires, and certainly THE KATIE SCHOOL OF weather. Rainfall and temperature have a significant INSURANCE 1 effect on agriculture, especially crops. Although every part of the world has its own weather patterns, and managing the risks associated with these patterns has ABSTRACT always been a part of life as a farmer, recent changes As a consequence of climate change, agriculture in in weather cycles resulting from increasing climate many parts of the world has become a riskier business change have increased the risk profile for farming and activity. Given the dependence on agriculture in adversely affected the ability of farmers to get loans. developing countries, this increased risk has a Farmers in developing countries may respond to losses potentially dramatic effect on the lives of people in ways that affect their future livelihoods such as throughout the developing world especially as it selling off valuable assets, or removing their children relates to their financial inclusion and sustainable from school and hiring them out to others for work. access to capital. This study analyzes the relationships They may also be unable to pay back loans in a timely between rainfall per crop gestation period (planting – manner, which makes rural banks and even harvesting) and crop yields and study the likelihood of microfinance institutions reluctant to provide them with crop yield losses. -

Colonial Land Policy and the Role of the Tindana in Northern Ghana

Research on Humanities and Social Sciences www.iiste.org ISSN (Paper)2224-5766 ISSN (Online)2225-0484 (Online) Vol.5, No.4, 2015 State and Non-State Actors in Land Appropriation: Colonial Land Policy and the Role of the Tindana in Northern Ghana Haruna Abdallah Imam Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, Legon, P.O. Box LG 73 Legon, Accra, Ghana E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper draws historical lines from Precolonial, Colonial to Postcolonial periods, linking colonial land policy to that of the state, and their effects on the traditional functions of the tindana (‘landowner’) in Dagbon. The office of the earthpriest was known throughout West Africa. Among the Dagbamba of Northern Ghana for example, the tindana did not only ‘own’ the land, but by reason of his or her ‘ownership’, was the only one who knew or was known by, the ‘spirit of the land’. Principally, the tindaamba (plural for tindana) appropriated land in the past, but with colonialism and subsequently independence, the power to distribute land has been vested in the chiefs and/or the state (Government of Ghana). In this sense, modernity has affected the role of the tindana. The paper concludes that the roles of the tindaamba in contemporary land issues are quite marginal. The influence they now enjoy is more apparent than real. Keywords : Tindana; Earth Priest; Dagbon; Yaan Naa; Land Policy 1. Introduction According to the oral traditions of the peoples of Northern Ghana, the indigenous inhabitants of the region were the Vagla, Sisala, Tampulensi and Guan who lived to the West of the White Volta (Boahen 1977). -

Chereponi Is Located in the North-East Region of Ghana Issue: Ethnic Armed Violence Date: March, 2019

NEWS SITUATION TRACKING - GHANA ETHNIC CLASHES IN CHEREPONI Location: Chereponi is located in the North-East Region of Ghana Issue: Ethnic Armed Violence Date: March, 2019 Source : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saboba_Chereponi COMMUNITY PROFILING CRITICAL INCIDENT PROFILING STAKEHOLDERS Population: The population of the Direct Actors: On 15th March 2019, a man known as Fahad Jababu Sulley (a district, according to the 2010 • The Komkombas and Chokosi, also Anufo by tribe) alleged to have crossed over to Population and Housing Census, is • The Anufors (Chokosis) Ghana from Togo, was shot and injured while sitting on a 55,932 of which 49.9% are males and motorbike outside of a home and in a group at Nawieku in the 50.4% are females, representing Affected Persons: Chereponi District of the newly created North-East Region. 2.3% of the Northern region’s total • About 2600 people have Security was beefed up in the area. population of 2,479,461 been affected so far, particularly women and However, on 16th March, 2019, the Konkombas allegedly Basic Demography and Geography children. attacked some Chokosis at Kornu, Nansoni, and Kpenchi. It has of Hotspots: • Affected communities been alleged that the Chokosis repelled the assailants and also Chereponi shares boundaries with the include Naaduuni, burnt some houses belonging to the Konkombas at Kpenchi, following Districts; Gushegu Achima, Tiakasu, Nabul and Ngbangbanu. On the same day, the Konkombas Municipal to the west; Bunkpurugu Kunkpende, Naaburubu, mounted road blocks on the Cherepone-Yendi road, sieved out Nyankpanduri District to the north, Kunajiiku, Sedorti, four Chokosis on a bus and manhandled them. -

Nanumba North District Assembly Bimbilla

NANUMBA NORTH DISTRICT ASSEMBLY BIMBILLA MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2014-2017) (BASED ON GHANA SHARED GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT AGENDA-GSGDA II) PREPARED BY: DISTRICT PLANNINIG COORDINATION UNIT BIMBILLA NOVEMBER 2013 10 | P a g e NANUMBA NORTH DISTRICT (2014 - 2017 MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN) ACRONYMS AC AREA COUNCIL AEA AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION AGENT AIDS ACQUIRED IMMUNED DEFICIENCY SYNDROME ART ANTI RETROVIRAL THERAPY CAPS COMMUNITY ACTION PLANS CBRDP COMMUNITY BASED RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT CCBT COMMUNITY CAPACITY BUILDING TEAM CHPS COMMUNITY HEALTH PLANNING SERVICES CRS CATHOLIC RELIEF SERVICES CSIR COUNCIL FOR SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH CWSA COMMUNITY WATER AND SANITATION AGENCY DA DISTRICT ASSEMBLY DADU DISTRICT AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT UNIT DCE DISTRICT CHIEF EXECUTIVE DDF DISTRICT DEVELOPMENT FACILITY DFR DEPARTMENT OF FEEDER ROADS DHMT DISTRICT HEALTH MANAGEMENT TEAM DMTDP DISTRICT MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN DPCU DISTRICT PLANNING CO-ORDINATING UNIT DWAP DISTRICT WIDE ASSISTANCE PROJECT EHU ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH UNIT EU EUROPEAN UNION 11 | P a g e NANUMBA NORTH DISTRICT (2014 - 2017 MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN) GDO GENDER DESK OFFICER GES GHANA EDUCATION SERVICE GSGDA GHANA SHARED GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT AGENDA GOG GOVERNMENT OF GHANA GPRS II GROWTH AND POVERTY REDUCTION STRATEGY HIV HUMAN IMMUNED VIRUS JHS JUNIOJR HIGH SCHOOL KVIP KUMASI VENTILATED IMPROVED PIT LI LEGISLATIVE INSTRUMENT M&E MONITORING AND EVALUATION MOE MINISTRY OF ENERGY MOFA MINISTRY OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE MTDP MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN NDPC -

District Profile

KPANDAI DISTRICT PROFILE 1.2.1 Introduction This section examines the geophysical characteristics of the District including the demography, culture, the district economy, social services, vulnerability as well as HIV/AIDs and gender, nature and status of the built environment as well as the current situation in relation to the seven pillars of the Medium-Term Development Policy Framework. 1.2.3 Geophysical Characteristics 1.2.3.1 Location and size The District can be located at the South-Eastern corner of the Northern Region of Ghana and lies between latitudes 8º N and 9.29º N and longitudes 0.29 º E and 1.26ºW. It is bordered to the North by Nanumba South District, East Gonja to the West, Krachi West District to the South-West, Nkwanta North District to the East and Pru District in Brong Ahafo Region to the South The District has a total surface area of 1,772.04sqkm with water covering about 5%. The District is strategically located – the central point between the Northern part and Southern part of the Eastern corridor of Ghana. The District can therefore take advantage of its strategic location to be a gateway to both the Southern and Northern Ghana. Similarly, strategic facilities of national importance aimed at wider coverage for both the southern and northern Ghana can be conveniently located in the district to achieve the desired results. Being strategically located in the transitional zone, the district has the advantage of experiencing mixed climatic conditions that have both positive and adverse implications for the district‟s development.