Address Biological Invasions in the Global and Australian Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NWC Australian Water Markets Report 2007-08

AUSTRALIAN WATER MARKETS REPORT 2007–2008 MARKETS REPORT WATER AUSTRALIAN National Water Commission Australian Water Markets Report 2007–2008 National Water Commission Australian Water Markets Report 2007–2008 © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at www.ag.gov.au/cca. ISBN 978-1-921107-70-2 Australian Water Markets Report 2007–2008, December 2008 Published by the National Water Commission 95 Northbourne Avenue Canberra ACT 2600 Tel: 02 6102 6000 Email: [email protected] Date of publication: December 2008 Design by Spectrum Graphics sg.com.au Printed on Dalton Revive Silk and ENVI Silk Printed by Canprint An appropriate citation for this publication is: National Water Commission 2008, Australian Water Markets Report 2007–2008, NWC, Canberra E N H O E U S National Water Commission R E G uses Greenhouse Friendly™ F R Y I E N D L ENVI Carbon Neutral Paper ENVI is an Australian Government CONSUMER certified Greenhouse Friendly™ Pr oduct. Revive Silk Cover is made from 25% post consumer and 25% pre consumer recycled fibre. It also contains elemental chlorine free pulp derived from sustainably managed forests and non-controversial sources. It is manufactured by an ISO 14001 certified mill. ENVI Coated is made from elemental chlorine free pulp derived from sustainably managed forests and non controversial sources. -

Gauging Station Index

Site Details Flow/Volume Height/Elevation NSW River Basins: Gauging Station Details Other No. of Area Data Data Site ID Sitename Cat Commence Ceased Status Owner Lat Long Datum Start Date End Date Start Date End Date Data Gaugings (km2) (Years) (Years) 1102001 Homestead Creek at Fowlers Gap C 7/08/1972 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 19.9 -31.0848 141.6974 GDA94 07/08/1972 16/12/1995 23.4 01/01/1972 01/01/1996 24 Rn 1102002 Frieslich Creek at Frieslich Dam C 21/10/1976 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 8 -31.0660 141.6690 GDA94 19/03/1977 31/05/2003 26.2 01/01/1977 01/01/2004 27 Rn 1102003 Fowlers Creek at Fowlers Gap C 13/05/1980 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 384 -31.0856 141.7131 GDA94 28/02/1992 07/12/1992 0.8 01/05/1980 01/01/1993 12.7 Basin 201: Tweed River Basin 201001 Oxley River at Eungella A 21/05/1947 Open DWR 213 -28.3537 153.2931 GDA94 03/03/1957 08/11/2010 53.7 30/12/1899 08/11/2010 110.9 Rn 388 201002 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.1 C 27/05/1947 31/07/1957 Closed DWR 124 -28.3151 153.3511 GDA94 01/05/1947 01/04/1957 9.9 48 201003 Tweed River at Braeside C 20/08/1951 31/12/1968 Closed DWR 298 -28.3960 153.3369 GDA94 01/08/1951 01/01/1969 17.4 126 201004 Tweed River at Kunghur C 14/05/1954 2/06/1982 Closed DWR 49 -28.4702 153.2547 GDA94 01/08/1954 01/07/1982 27.9 196 201005 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.3 A 3/04/1957 Open DWR 111 -28.3096 153.3360 GDA94 03/04/1957 08/11/2010 53.6 01/01/1957 01/01/2010 53 261 201006 Oxley River at Tyalgum C 5/05/1969 12/08/1982 Closed DWR 153 -28.3526 153.2245 GDA94 01/06/1969 01/09/1982 13.3 108 201007 Hopping Dick Creek -

Gazette No 145 of 19 September 2003

9419 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEWNew SOUTH South Wales WALES Electricity SupplyNumb (General)er 145 AmendmentFriday, (Tribunal 19 September and 2003 Electricity Tariff EqualisationPublished under authority Fund) by cmSolutions Regulation 2003LEGISLATION under the Regulations Electricity Supply Act 1995 Her Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has made the following Regulation Newunder South the WalesElectricity Supply Act 1995. Electricity Supply (General) Amendment (Tribunal and Electricity TariffMinister for Equalisation Energy and Utilities Fund) RegulationExplanatory note 2003 The object of this Regulation is to prescribe 30 June 2007 as the date on which Divisions under5 and 6the of Part 4 of the Electricity Supply Act 1995 cease to have effect. ElectricityThis Regulation Supply is made Act under 1995 the Electricity Supply Act 1995, including sections 43EJ (1), 43ES (1) and 106 (the general regulation-making power). Her Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has made the following Regulation under the Electricity Supply Act 1995. FRANK ERNEST SARTOR, M.P., Minister forfor EnergyEnergy and and Utilities Utilities Explanatory note The object of this Regulation is to prescribe 30 June 2007 as the date on which Divisions 5 and 6 of Part 4 of the Electricity Supply Act 1995 cease to have effect. This Regulation is made under the Electricity Supply Act 1995, including sections 43EJ (1), 43ES (1) and 106 (the general regulation-making power). s03-491-25.p01 Page 1 C:\Docs\ad\s03-491-25\p01\s03-491-25-p01EXN.fm -

Bald Rock and Boonoo Boonoo National Parks Plan of Management

BALD ROCK AND BOONOO BOONOO NATIONAL PARKS PLAN OF MANAGEMENT BALD ROCK AND BOONOO BOONOO NATIONAL PARKS PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service February 2002 This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for the Environment on 22nd January 2002. Acknowledgments: The principal author of this plan of management is Kevin Parker, Ranger, Northern Tablelands Region. Special thanks to Gina Hart, Stuart Boyd-Law, Peter Croft, Jamie Shaw, Stephen Wolter and Bruce Olson for their valuable assistance. The input of the members of the Steering Committee, the Northern Directorate Planning Group, and Head Office Planning Unit is gratefully acknowledged. Cover photo: Aerial view of Bald Rock. Photo by Kevin Parker. NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service © Crown Copyright 2002 Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgment ISBN 0 7313 6330 2 OEH 2016/0305 First published 2002 Updated with map May 2016 FOREWORD Bald Rock and Boonoo Boonoo National Parks are situated approximately 30 km north- east of Tenterfield on the far northern tablelands of New South Wales. Both parks form part of a system of conservation areas representing environs of the northern granite belt of the New England Tablelands. The two parks and the adjoining Girraween National Park in Queensland are of regional conservation significance as they provide protection for the most diverse range of plant and animal communities found in the granite belt, as well as several species and communities endemic to the area. They also contain spectacular landscape features such as Bald Rock, a huge granite dome, and the magnificent Boonoo Boonoo Falls, both of which are major visitor attractions to the area. -

Our Water Our Country

Our Water Our Country An information manual for Aboriginal people and communities about the water reform process Our Water Our Country An information manual for Aboriginal people and communities about the water reform process warning users of this manual should be aware that it contains images of people who are now deceased Edition 2.0 February 2012 Published by: NSW Department of Primary Industries, NSW Office of Water Level 18, 227 Elizabeth Street GPO Box 3889 Sydney NSW 2001 T 02 8281 7777 F 02 8281 7799 [email protected] www.water.nsw.gov.au The NSW Office of Water manages the policy and regulatory frameworks for the state’s surface water and groundwater resources, to provide a secure and sustainable water supply for all users. It also supports water utilities in the provision of water and sewerage services throughout New South Wales. The Office of Water is a division of the NSW Department of Primary Industries. Preferred way to cite this publication: NSW Office of Water 2012. Our Water Our Country: An information manual for Aboriginal people and communities about the water reform process. Edition 2.0. NSW Department of Primary Industries, Office of Water, Sydney, NSW. Copyright information © State of New South Wales through the Department of Trade and Investment, Regional Infrastructure and Services, 2012 This material may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, providing the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are clearly and correctly acknowledged. Disclaimer: While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at the time of publication, the State of New South Wales, its agents and employees, disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect of anything or the consequences of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance upon the whole or any part of this document. -

Tenterfield Final Report 2015

FINAL REPORT 2015 Rolling hills to the east of Tenterfield Tenterfield LGA Contract Area New England Contract No 742342 Prepared for LPI Under Rating & Taxing Procedure Manual 6.6.2 Opteon Property Group Opteon (Northern Inland NSW) 536 Peel Street Tamworth NSW 2340 P 02 6766 3442 E [email protected] F 02 6766 5801 W www.opg.net VALUE MADE VISIBLE Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation Tenterfield LGA 2015 Final Report Executive Summary LGA Overview Tenterfield Local Government Area Tenterfield Local Government Area (LGA) is located in northern New South Wales, approximately 700 kilometres to the north of the Sydney in the New England Region of New South Wales. Tenterfield LGA comprises a land area of approximately 7,332 square kilometres that predominantly includes sheep and cattle grazing with some small areas of cropping on the better river flats adjoining the Dumaresq and Clarence Rivers. Some diversification in use of rural land is evident with a number of vineyards around Tenterfield Town. The LGA is adjoined by four other LGAs – Kyogle Council north-east, Clarence Valley Council to the south-east, Glen Innes Severn Council to the south and Inverell Shire Council to the south-west. Number of properties valued this year and the total land value in dollars Tenterfield LGA comprises Village, Rural, and Forestry zones. 5,026 properties were valued at the Base Date of 1 July 2015, and valuations are reflective of the property market at that time. Previous Notices of Valuation issued to owners for the Base Date of 1 July 2013. -

NCD2017/002 Schedule Three

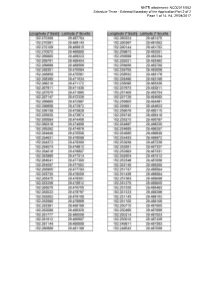

NNTR attachment: NCD2017/002 Schedule Three - External Boundary of the Application Part 2 of 2 Page 1 of 14, A4, 29/08/2017 NNTR attachment: NCD2017/002 Schedule Three - External Boundary of the Application Part 2 of 2 Page 2 of 14, A4, 29/08/2017 Then north westerly to the southernmost corner of an unnamed road which bisects the southern boundary of Lot 1 on DP751494; then generally northerly along the eastern boundaries of that unnamed road to Latitude 29.394977° South; then generally northerly through the following coordinate points; NNTR attachment: NCD2017/002 Schedule Three - External Boundary of the Application Part 2 of 2 Page 3 of 14, A4, 29/08/2017 NNTR attachment: NCD2017/002 Schedule Three - External Boundary of the Application Part 2 of 2 Page 4 of 14, A4, 29/08/2017 NNTR attachment: NCD2017/002 Schedule Three - External Boundary of the Application Part 2 of 2 Page 5 of 14, A4, 29/08/2017 Then northerly to an eastern boundary of the Upper Rocky River road reserve at Latitude 29.334920° South; then generally northerly along the eastern boundaries of that road reserve to Latitude 29.209676° South; then generally northerly through the following coordinate points; Then northerly to again an eastern boundary of Upper Rocky River road reserve at Latitude 29.200911° South; then generally northerly along the eastern boundaries of that road reserve to its intersection with the southern boundary of Billarimba road reserve; then northerly to the northern boundary of that road reserve at Longitude 152.249268° East; then generally north -

Download Full Article 202.0KB .Pdf File

Memoirs of Museum Victoria 58(2): 247–254 (2001) REDESCRIPTION OF BUNGONA HARKER WITH NEW SYNONYMS IN THE AUSTRALIAN BAETIDAE (INSECTA: EPHEMEROPTERA) P. J. SUTER AND M. J. PEARSON CRC for Freshwater Ecology, Department of Environmental Management and Ecology, La Trobe University Albury-Wodonga Campus, PO Box 821, Wodonga, Victoria 3689, Australia [email protected] Abstract Suter, P.J. and Pearson, M.J., 2001. Redescription of Bungona Harker with new synonyms in the Australian Baetidae (Insecta: Ephemeroptera). Memoirs of Museum Victoria 58(2): 247–254. The monospecific genus Bungona Harker is redefined and descriptions of the imago and nymphs of Bungona narilla Harker are provided. Two species described by Lugo-Ortiz and McCafferty (1998) as Cloeodes fustipalpus and C. illiesi are recognised as being conspecific and junior synonyms of Bungona narilla. Bungona narilla is distributed along the east coast of Australia from North Queensland to Tasmania and nymphs occur in shallow, slow flowing, cobble streams. Introduction papers. The two species clearly belong in Bung- ona as redefined by Dean and Suter (1996) and Harker (1957) erected the genus Bungona and subsequently verified. Bungona has numerous Bungona narilla, type species, on the basis of a nymphal and imaginal characteristics which dis- nymph and adult from Coal and Candle Creek, tinguish it from Cloeodes as defined by Traver Sydney. The adult was distinguished from the (1938) and redefined by Waltz and McCafferty genus Pseudocloeon by the shape and number of (1987a, b). Character states of C. fustipalpus and segments of the forceps and the nymphs were dis- C. illiesi are within the variation of Bungona tinguished by the shape of the labial palpi and the narilla and both are treated as junior synonyms of maxillary palpi being 3-segmented. -

Find Your Local Brigade

Find your local brigade Find your district based on the map and list below. Each local brigade is then listed alphabetically according to district and relevant fire control centre. 10 33 34 29 7 27 12 31 30 44 20 4 18 24 35 8 15 19 25 13 5 3 45 21 6 2 14 9 32 23 1 22 43 41 39 16 42 36 38 26 17 40 37 28 11 NSW RFS Districts 1 Bland/Temora 13 Hawkesbury 24 Mid Coast 35 Orana 2 Blue Mountains 14 Hornsby 25 Mid Lachlan Valley 36 Riverina 3 Canobolas 15 Hunter Valley 26 Mid Murray 37 Riverina Highlands 4 Castlereagh 16 Illawarra 27 Mid North Coast 38 Shoalhaven 5 Central Coast 17 Lake George 28 Monaro 39 South West Slopes 6 Chifley Lithgow 18 Liverpool Range 29 Namoi Gwydir 40 Southern Border 7 Clarence Valley 19 Lower Hunter 30 New England 41 Southern Highlands 8 Cudgegong 20 Lower North Coast 31 North West 42 Southern Tablelands 9 Cumberland 21 Lower Western 32 Northern Beaches 43 Sutherland 10 Far North Coast 22 Macarthur 33 Northern Rivers 44 Tamworth 11 Far South Coast 23 MIA 34 Northern Tablelands 45 The Hills 12 Far West Find your local brigade 1 Find your local brigade 1 Bland/Temora Springdale Kings Plains – Blayney Tara – Bectric Lyndhurst – Blayney Bland FCC Thanowring Mandurama Alleena Millthorpe Back Creek – Bland 2 Blue Mountains Neville Barmedman Blue Mountains FCC Newbridge Bland Creek Bell Panuara – Burnt Yards Blow Clear – Wamboyne Blackheath / Mt Victoria Tallwood Calleen – Girral Blaxland Cabonne FCD Clear Ridge Blue Mtns Group Support Baldry Gubbata Bullaburra Bocobra Kikiora-Anona Faulconbridge Boomey Kildary Glenbrook -

Annual Report 2019 - 2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 - 2020 This document was produced and is available from Tenterfield Shire Council. Tenterfield Shire Council 247 Rouse Street PO Box 214 TENTERFIELD NSW 2372 Telephone: (02) 6736 6000 Website: www.tenterfield.nsw.gov.au Email: [email protected] © Tenterfield Shire Council 2019 Contents Mayor’s Message................................................................................................................. 1 Chief Executive’s Message ............................................................................................. 2 About Council ....................................................................................................................... 3 Community Strategic Plan Achievements .............................................................. 15 Community ...................................................................................................................... 19 Economy ........................................................................................................................... 23 Environment.................................................................................................................... 27 Leadership ....................................................................................................................... 31 Transport .......................................................................................................................... 39 Statutory Reporting ........................................................................................................ -

The National Water Planning Report Card 2013

National Water Commission The National Water Planning Report Card 2013 © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This publication is available for your use under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence, with the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, the National Water Commission logo and where otherwise stated. The full licence terms are available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/au/ Use of National Water Commission material under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence requires you to attribute the work in all cases when reproducing or quoting any part of a Commission publication or other product (but not in any way that suggests that the Commonwealth or the National Water Commission endorses you or your use of the work). Please see the National Water Commission website copyright statement http://www.nwc.gov.au/copyright for further details. Other uses Enquiries regarding this licence and any other use of this document are welcome at: Communication Director National Water Commission 95 Northbourne Avenue Canberra ACT 2600 Email: [email protected] National Water Planning Report Card 2013 September 2014 ISBN: 978-1-922136-36-7 Designed by giraffe.com.au An appropriate citation for this publication is: National Water Commission 2014, National Water Planning Report Card 2013, NWC, Canberra National Water Commission | Water Planning Report Card 2013 | i 95 Northbourne Avenue Canberra ACT 2600 T 02 6102 6000 nwc.gov.au Chair Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for the Environment Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Senator Birmingham I am pleased to present to you the National Water Commission’s National Water Planning Report Card 2013. -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 197 Friday, 19 December 2003 Published Under Authority by Cmsolutions

11253 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 197 Friday, 19 December 2003 Published under authority by cmSolutions LEGISLATION Assents to Acts ACTS OF PARLIAMENT ASSENTED TO Legislative Assembly Office, Sydney, 25 November 2003 IT is hereby notified, for general information, that Her Excellency the Governor has, in the name and on behalf of Her Majesty, this day assented to the undermentioned Acts passed by the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council of New South Wales in Parliament assembled, viz.: Act No. 75 2003 - An Act to appropriate out of the Consolidated Fund the sum of $420,000,000 towards public health capital works and services; and for other purposes. [Appropriation (Health Super-Growth Fund) Bill] Act No. 76 2003 - An Act to amend the Evidence (Audio and Audio Visual Links) Act 1998 and the Evidence Legislation Amendment (Accused Child Detainees) Act 2003 to make further provision with respect to the giving of evidence by accused detainees; and for other purposes. [Evidence (Audio and Audio Visual Links) Amendment Bill] Act No. 77 2003 - An Act to amend various superannuation Acts to accommodate Commonwealth legislation relating to the division of superannuation entitlements on marriage breakdown, to extend benefits to de facto partners in certain schemes and to update pension adjustment provisions; and for other purposes. [Superannuation Legislation Amendment (Family Law) Bill] Russell D. Grove PSM Clerk of the Legislative Assembly 11254 LEGISLATION 19 December 2003 19 December 2003 LEGISLATION 11255 ACTS OF PARLIAMENT ASSENTED TO Legislative Assembly Office, Sydney, 27 November 2003 IT is hereby notified, for general information, that Her Excellency the Governor has, in the name and on behalf of Her Majesty, this day assented to the undermentioned Acts passed by the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council of New South Wales in Parliament assembled, viz.: Act No.